A former professional footballer and itinerant worker, Ives was fascinated by folk-songs, researching them and singing them for records, radio and night-clubs. The ballads in Smoky were not unknown in Britain but, since the film hardly started a stampede to the box-office, Ives’s recordings took a while to get off the ground here. In particular, “The Blue Tail Fly” and “The Big Rock Candy Mountain” became popular in the mid-Fifties – while Ives was simultaneously making a career as a character actor in movies.

His identification with folk singing began after he had been in show business for some time. In Rodgers and Hart’s The Boys From Syracuse (1938) he had a small part as tailor’s apprentice, and during the Second World War he sang “God Bless America” and Irving Berlin songs in the touring company of This is the Army. In 1944 he was invited to appear at the Village Vanguard, a night-club frequented by middle-class intellectuals. It had just had a great success with a satirical group, “The Revuers”, whom we know as Judy Holliday, Betty Comden and Adolph Green. Rather than trying to find similar acts, the Vanguard followed with Ives, Josh White, Richard Dyer-Bennett and other folk-singers: and it could be argued that the smart people of Manhattan were looking for the sort of Americana with which they were not familiar.

Certainly these performers all moved uptown to the Blue Angel, the watering- place for caf society in the late 1940s. In the meantime Ives was cast in a Broadway show, Sing Out, Sweet Land (1946), a celebration of old and/or patriotic songs to reflect the post-war mood – and the more folksy ones appealed to Fox, who invited Ives to reprise some of his in order to liven up its otherwise mundane horse opera.

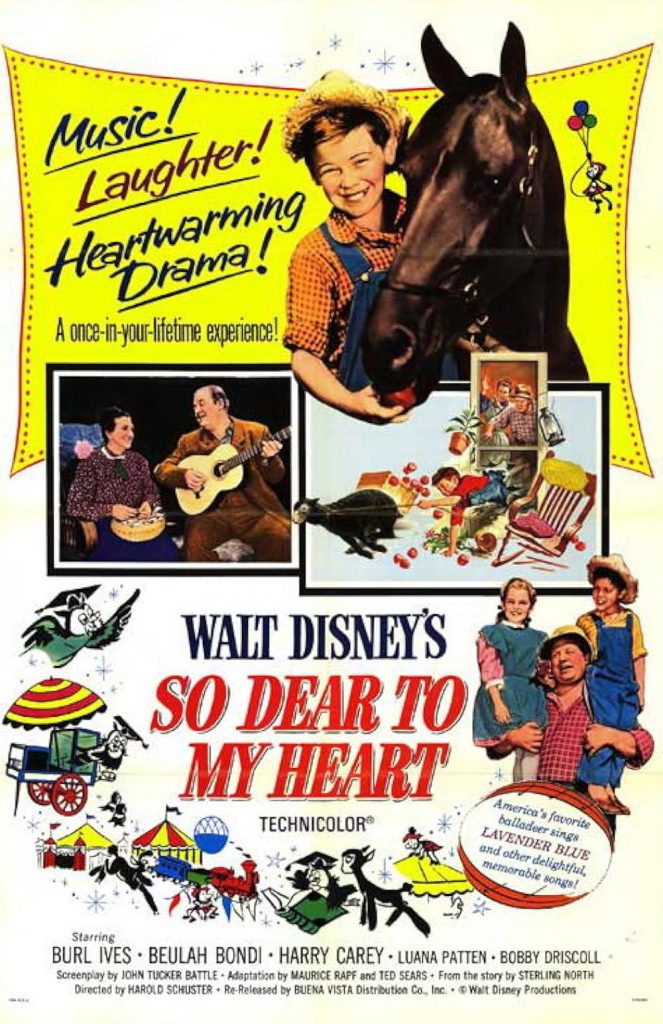

He returned to the studio to help out another of this seemingly interminable series, Green Grass of Wyoming (1948), after which Walt Disney chose him to play kindly Uncle Hiram in So Dear to My Heart (1949), based on Sterling North’s novel Midnight and Jeremiah, about a boy who adopts a black sheep. Disney’s child star, Bobby Driscoll (later to die an anonymous drug addict in an untenanted building), was Jeremiah, while as his granny Beulah Bondi was as sympathetic as Ives – who sang a ditty based on a folk-song, “Lavender Blue”, which brought an Academy Award nomination for its two adaptors.

Ives did not restrict himself to old songs, but chose many, such as “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer”, which suited his avuncular down-home image. It was not entirely in keeping with the private Ives.

Sing Out, Sweet Land was the first production directed by the drama critic Walter Kerr, who in his inexperience called in Elia Kazan for assistance. Kazan, who enjoyed Ives’s larger-than-life personality, nevertheless recalled seeing him “drunk one night, macho and rampant, aroused to a point where he was looking for a fight, anywhere and with anybody. He was a formidable man, with a frightening temper; he evoked respect for his violence. Late one night, soused again, he reversed his emotion and I was afraid that he was about to throw himself out of a window.”

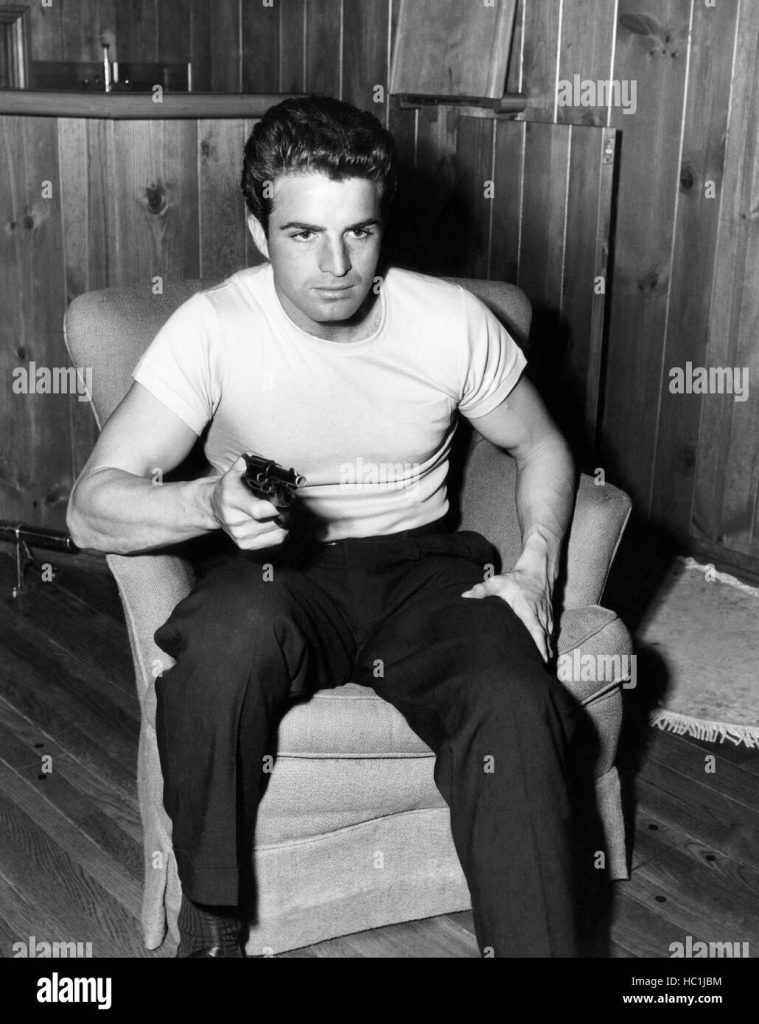

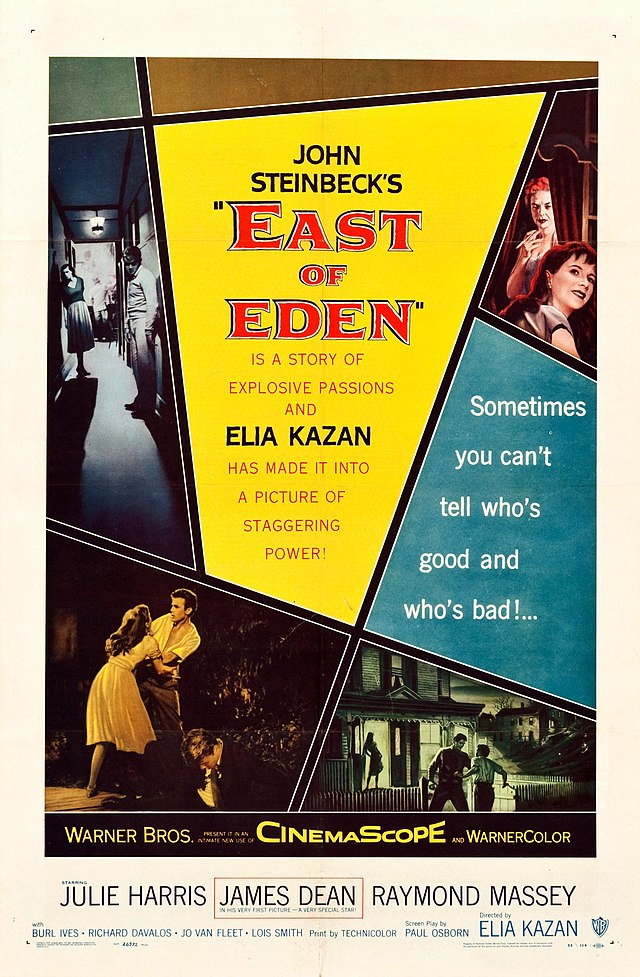

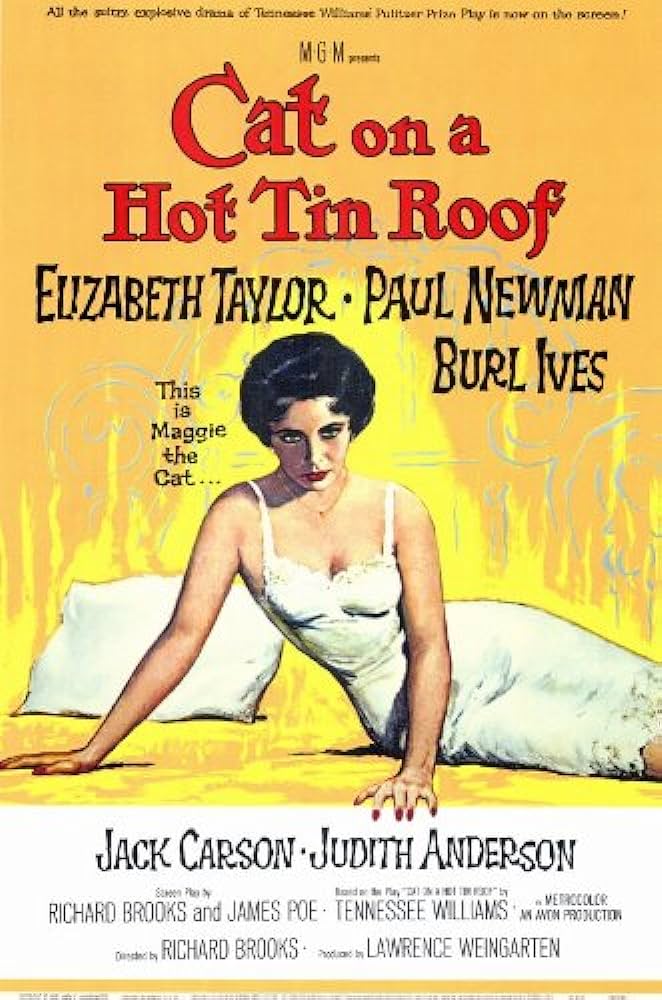

Ives, whose left-wing views were well-known, gave evidence to the committee at the McCarthy hearings – as did Kazan, Budd Shulberg and others, though only Kazan was to remain in contumely for a long time. He was also the most famous of those who confessed and continued to work; Ives’s budding film career was blighted till Kazan chose him to play the tough but understanding sheriff who takes James Dean under his wing in East of Eden (1955); then, remembering his ferocity and contempt for good manners, he cast him as the red-necked bullying Big Daddy in Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

It was a bravura role with a pages-long tirade, and Williams wasn’t sure that Ives could do it, but Kazan knew that he could – “straight out: that was where he had the confidence born of his concert experience, that was the style of performing that he – and I – enjoyed.” Williams, who had based the role on his own father, told Ives that “on opening night he sat in the 14th row and saw Cornelius Williams”.

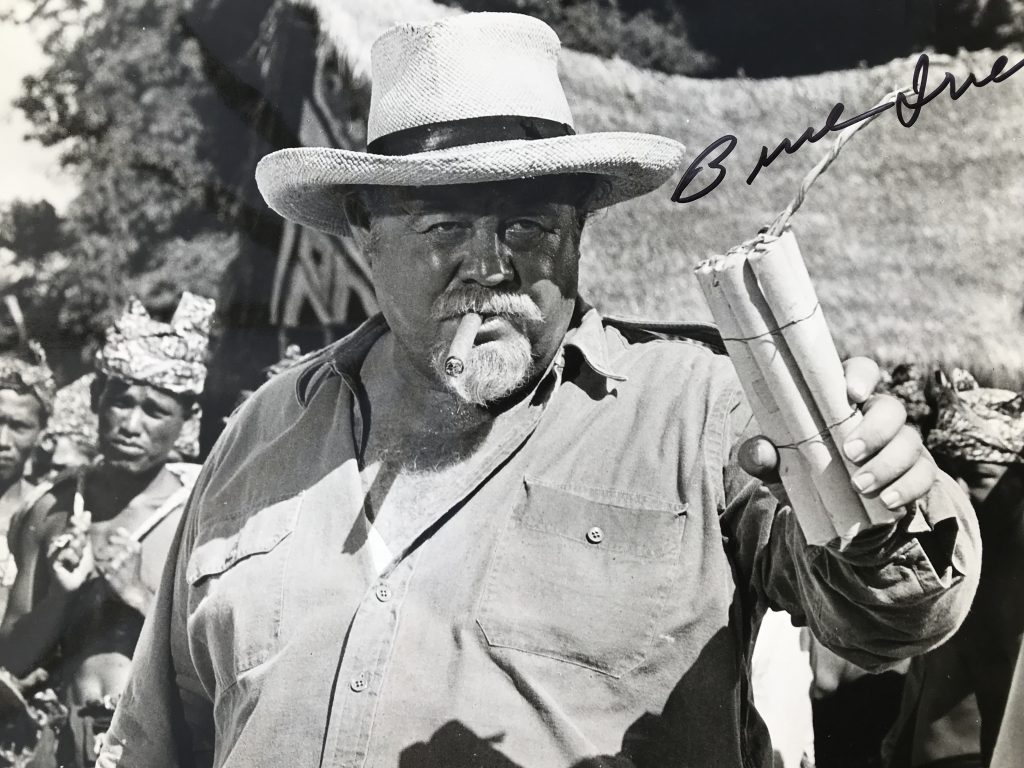

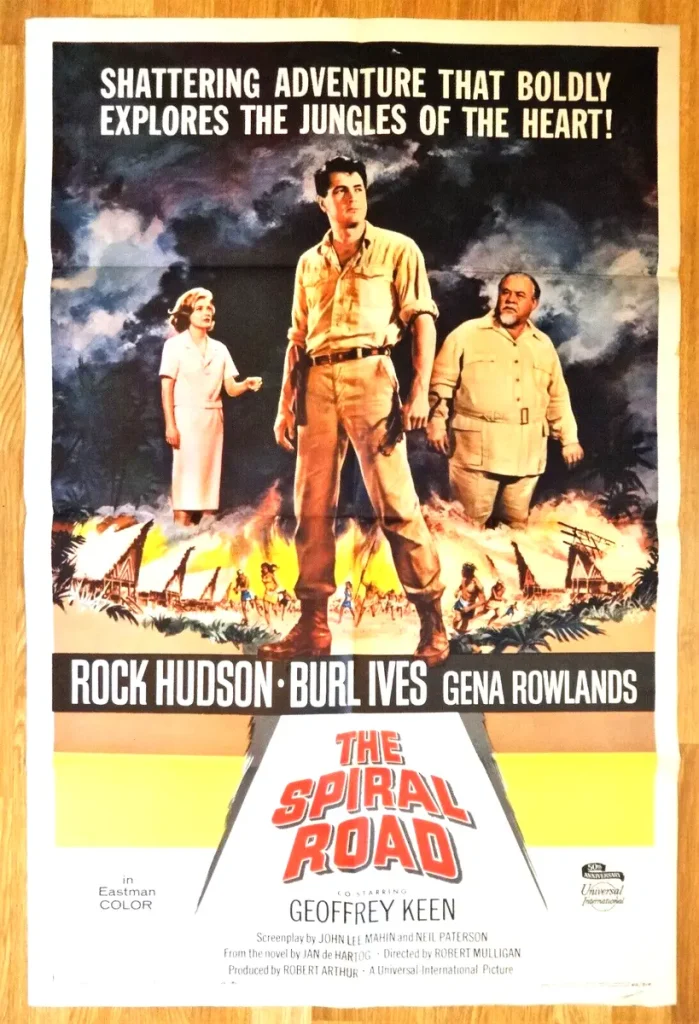

The role revitalised Ives’s career. He was offered night-club engagements in the sort of territory then unknown for folk-singers, Las Vegas – though by now he was less of a folk archivist than an entertainer courting the widest popular public. He returned to films in star roles, all based to an extent on Big Daddy, beginning with the ruthless and monomaniacal company president in a Robert Taylor vehicle, The Power and the Prize (1956). He was top-billed as the renegade leader of the Swamp Angels in Wind across the Everglades (1958), directed by Nicholas Ray and produced and written by Budd Shulberg. Admittedly his co-stars, Christopher Plummer and Gypsy Rose Lee, were not household names; and he was billed after Sophia Loren and Anthony Perkins in Delbert Mann’s version of Eugene O’Neill’s Desire under the Elms. Since Loren, as the new wife, and Perkins, as the son who cuckolds him, were both miscast, Ives seems to have hoped to get through the ordeal with one hangdog expression.

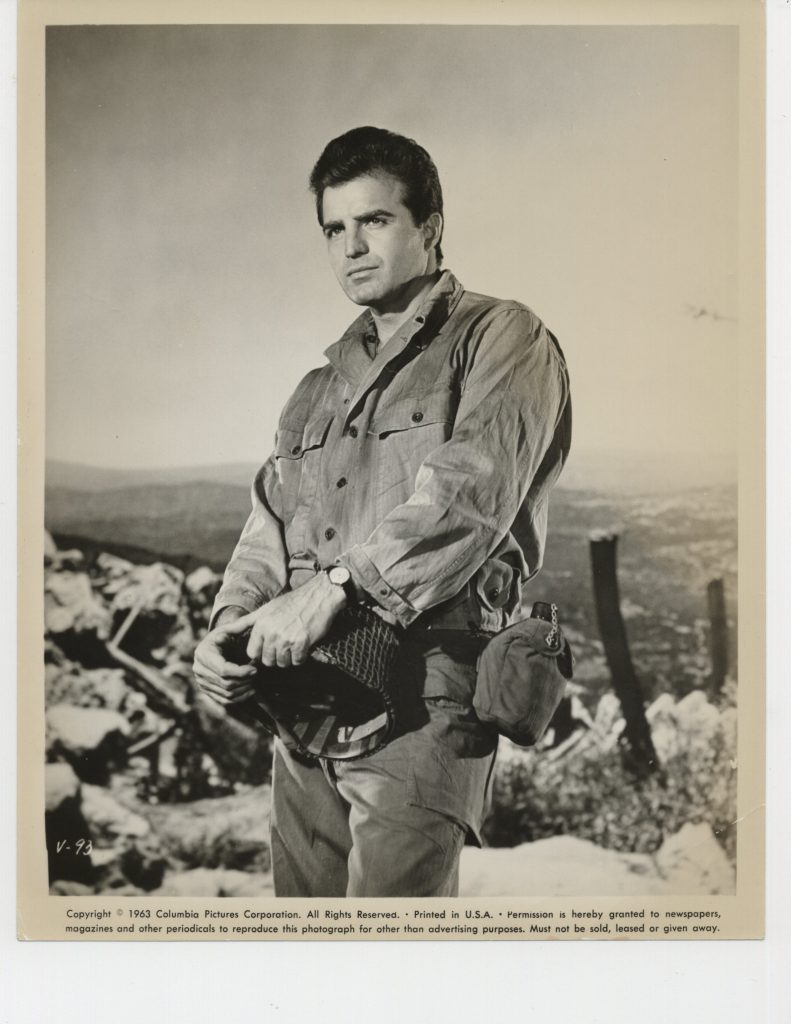

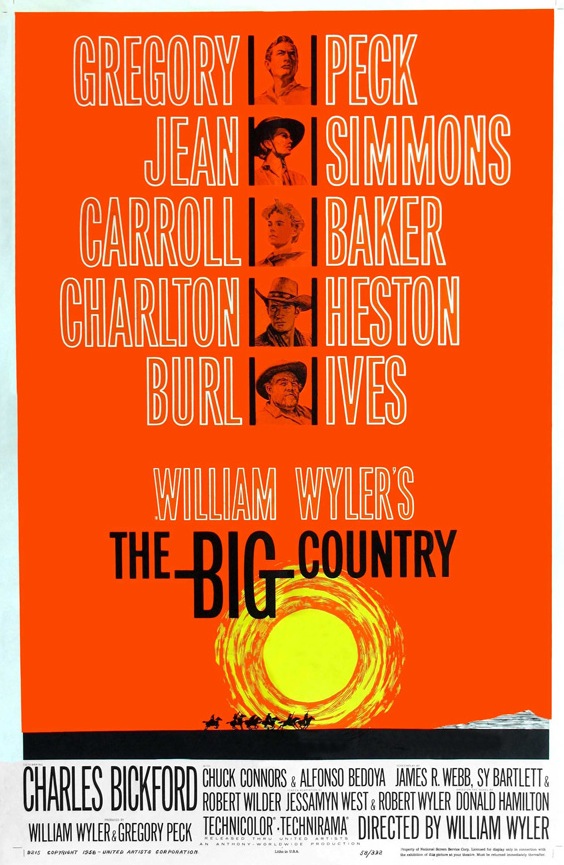

Although Kazan chose not to direct the film of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof – Richard Brooks did – Ives was the only possible choice for Big Daddy, but he was not nominated for an Oscar because MGM insisted that he should be shortlisted for Best Actor. More realistically, United Artists put him up for a Best Supporting Oscar in William Wyler’s The Big Country, in which he played a white-trash land baron at war with the more likeable Charles Bickford. When he won that Oscar the Hollywood Reporter somewhat cruelly referred to the film as “Big Daddy Goes West”. He was a mysterious refugee from Hitler in Our Man in Havana (1959), directed by Carol Reed from a Graham Greene screenplay (from his own novel), which with those two films is the highwater mark of Ives’s career.

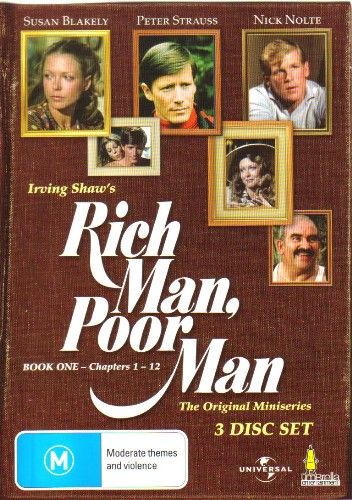

Burl Ives was equally convincing whether nice or nasty, but both his rotund figure and his age – not to mention an unkempt goatee – fitted him only for character roles. Those assigned him in later movies were not distinguished, and he was better served by films and mini-series made for television. Ill-health had prevented him from working in recent years.

Although not to everybody’s taste, the pretty modern ditties he recorded should be around for a while yet. He had a hit parade entry in the early Sixties with “Itty Bitty Tear” and again with “The Ugly Bug Ball”, which he had sung in his role of the postmaster in Summer Magic (1963), based on Mother Carey’s Chickens by Kate Douglas Wiggins. The song was written by Richard and Robert Sherman, then warming up for Mary Poppins. The film brought Ives’s career full circle, for the lead was played by the only other genuine Disney child star – apart from Master Driscoll – Hayley Mills.

David Shipman

The above “Independent” obituary can be accessed online here.