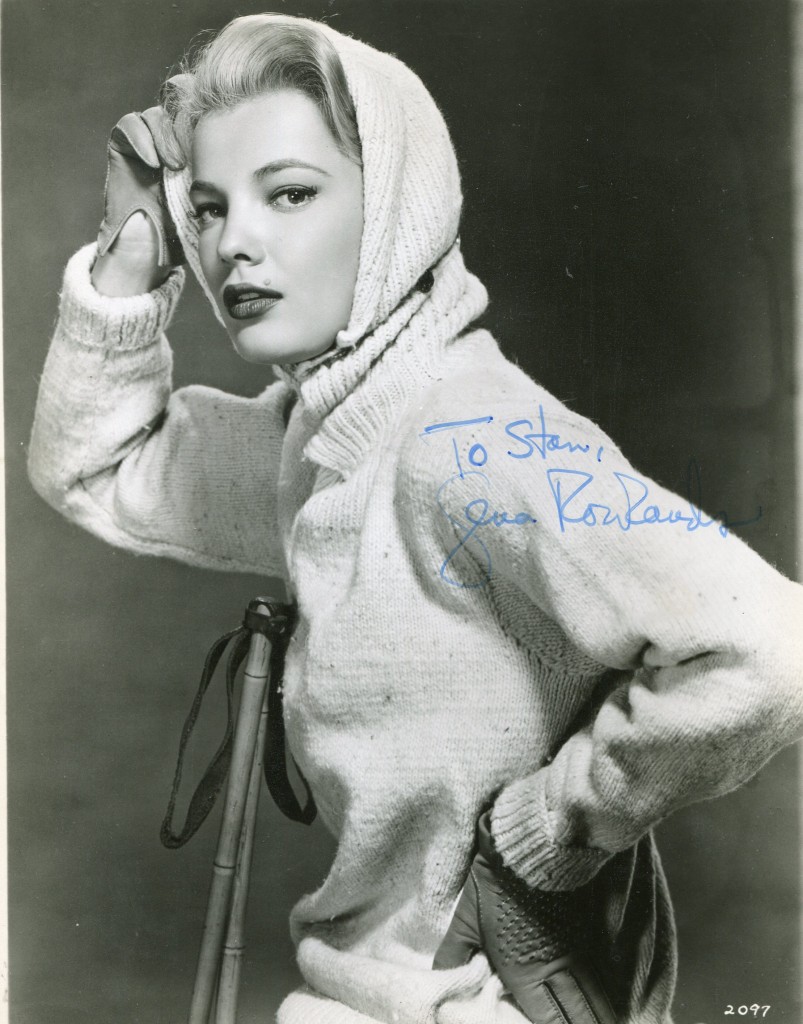

Gena Rowlands, who has died aged 94, was in the tradition of formidable performers such as Bette Davis and Joan Crawford yet, unlike them, she always remained an actor rather than a star. She was, said the critic Kent Jones, “finally a little too weird for superstardom”.

She did her most fearless work as part of an informal repertory company (also including Peter Falk, Ben Gazzara and Seymour Cassel) in a string of dense, demanding and highly charged films by her husband, the devoutly independent director John Cassavetes, who favoured rawness and improvisation but scorned compromise. The most comparatively gentle of their collaborations was Minnie and Moskowitz (1971), in which she and Cassel gave what the critic Roger Ebert called “performances so beautiful you can hardly believe it” as mismatched lovers.

Their characters were based loosely on Rowlands and Cassavetes themselves, right down to her penchant for wearing sunglasses at night and his dishevelled appearance.

In A Woman Under the Influence (1974), arguably the couple’s joint masterpiece, Rowlands combined scalding intensity with unflinching vulnerability as Mabel, a wife and mother whose mental health is fast degrading, opposite Falk as her uncomprehending husband. Jones described her performance as “an imaginative feat”, characterised by “her abstracted turns of the head and hands, her overemphatic emotional responses, her violent attempts to eradicate potentially threatening impulses”. It earned her the first of two Oscar nominations.

Opening Night (1977) was an extended, Bergman-esque character study of Myrtle, an actor contending simultaneously with the death of a fan, her own fears that she is over-the-hill, and a sudden loss of faith in her own talent. Now highly regarded, it was panned on its initial US release and played to near-empty cinemas, though Rowlands was rewarded for yet another blistering performance with the best actress prize at the Berlin film festival.

In Cassavetes’s most commercial film, Gloria (1980), she was dynamic as a gun-toting former showgirl protecting a young boy from the mob. The role only came her way after Barbra Streisand turned it down on the basis that it was “too maternal” and “not glamorous enough”. But it brought Rowlands a second Oscar nomination and catered perfectly to her knack for lacing tenderness with grit.

It was precisely that combination to which she responded in her screen idol, Marlene Dietrich. “Rowlands was fascinated with Dietrich’s blend of feminine sexual allure and almost masculine toughness and swagger,” wrote Cassavetes’s biographer, Ray Carney, who noted that she even “adopted a few of Dietrich’s gestures and mannerisms” after becoming obsessed with The Blue Angel while working as a cinema usher in 1950.

She was born in Madison, Wisconsin, the daughter of Mary Ellen (nee Neal), an artist and actor, and Edwin Rowlands, a banker and politician, and was something of a sickly child. When her father was appointed, in 1939, to the US department of agriculture, the family moved to Washington DC; they later moved back to Wisconsin, then to Minnesota.

Rowlands studied English at the University of Wisconsin, but her deep desire to become an actor led her to abandon her studies and depart for the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York, with her parents’ blessing. It was there that she met Cassavetes, whom she married in 1954. “It was a hard struggle to convince Gena,” he said. “We agree in taste on absolutely nothing.”

As Carney pointed out, he was “the fast-talking, street-smart city boy. Rowlands was socially smooth and refined; Cassavetes rough-hewn, impulsive, passionate and driven. She cared what people thought; he didn’t. She was cool, poised, charming; he was half-crazy, hot-blooded and Mediterranean. Sparks flew.”

She began her career in repertory and summer stock and was spotted in a production at Provincetown Playhouse, Cape Cod (where she also worked as a wardrobe mistress), which led to her being cast as the Mistress of Ceremonies in All About Love at the Versailles Nightclub theatre in New York in 1951. During a period of unemployment, she wrote storylines for the Crime Does Not Pay comic books (“I could tell you what any three-time loser got for assault and battery in any prison in the country”) before first appearing on Broadway as the understudy for the lead in The Seven Year Itch, later taking over the role and touring with it.

She appeared in Dangerous Corner off-Broadway in 1953 and, two years later, was in The Great Gatsby, part of the Robert Montgomery Presents series, on television. After starring opposite Edward G Robinson in Middle of the Night on Broadway in 1956, she signed to MGM and appeared with José Ferrer in her first film, The High Cost of Loving (1958) – although sadly she was not noticed, since it flopped badly (“I think maybe 50 people saw it,” she said).

She insisted that “I wasn’t planning to go into pictures at all,” yet film and television were to take over her career. She played a small, albeit leading, role opposite Kirk Douglas in the fine Lonely Are the Brave (1962), which remained one of her favourites, and was then directed by Cassavetes in A Child Is Waiting (1963). She had made a brief appearance in her husband’s debut, Shadows (1958), an independent production that broke all the rules of film-making.

It was made for a tiny budget with a borrowed camera, with no prospect of being widely shown, yet became a critical and commercial success. Faces (1968), in which Rowlands played a sex worker, equally took the world by storm.

Her performances for Cassavetes are glorious and Rowlands probably never exceeded their power. He directed her in his penultimate film, Love Streams (1984), which reunited her and Cassel, Minnie and Moskovitz themselves, this time as a former couple, now divorced and disillusioned.

The central relationship, though, is between her and Cassavetes, who plays her brother. “Cassavetes and Rowlands, sharing the screen for the last time, edge their performances into tragicomic slapstick,” wrote the critic Dennis Lim. As Jones put it: “Theirs would be one of the cinema’s greatest and most complex on-screen love affairs, if not for the simple fact that it plumbs so much deeper than mere infatuation.”

Their final collaboration came in 1987, two years before Cassavetes’s death from cirrhosis of the liver, when he directed Rowlands and Carol Kane in his play A Woman of Mystery at the Court theatre in Los Angeles. In an otherwise unimpressed review, the LA Times singled out Rowlands, who played a woman going up in the world, as “a strong presence … the feeling is that of a valiant woman who will keep going until she comes to a better place”.

Rowlands made a wealth of other work. She played the mother trying to do right by her children in Paul Schrader’s underrated Light of Day (1987) and the lead in Woody Allen’s Another Woman (1988), which took her away from the more physically extroverted Cassavetes roles. In Allen’s film, in which she portrayed a character who has consistently repressed her emotions, her lovely, shoulder-length blond hair was tied back and darkened. Unfairly, the film was a critical failure and Rowlands’s extraordinary performance was rather overlooked in favour of Gene Hackman’s brief appearances.

Her co-star in Jim Jarmusch’s Night on Earth (1991), Winona Ryder, said that the way Rowlands lit a cigarette was the best argument for smoking that she had ever seen. Rowlands was cast as an ageing smalltime cabaret singer in Terence Davies’s The Neon Bible (1995). She insisted that “I can’t sing, I can’t hit all the notes”, but for Davies that was what made her so moving.

She was directed by her son Nick in Unhook the Stars (1996), co-starring Gérard Depardieu, and also took parts in Nick’s later films She’s So Lovely (1997), which had a screenplay by John Cassavetes, the weepie The Notebook(2004) and the unconventional Yellow (2012).

In 2006, she wrote the screenplay for and appeared in a segment, directed by Depardieu and Frédéric Auburtin, of the omnibus film Paris, Je T’Aime. The story of a couple who meet for drinks the night before they sign their divorce papers, it co-starred Gazzara. In 2007 she had a supporting role in Broken English, written and directed by her daughter Zoe, and in 2008 provided a voice for the animated film Persepolis.

Olive (2011), in which Rowlands played Tess, was the first full-length film shot entirely on a smartphone. In 2014, she and Frank Langella played a couple facing biological weapons attack in Parts Per Billion; and she and Cheyenne Jackson were a teacher and pupil forming a friendship through dance in Six Dance Lessons in Six Weeks.

Throughout her career, Rowlands consistently took roles on television, including in live productions of the 1950s. She appeared in series such as Laramie (1959), Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1960), 87th Precinct (1961-62), The Virginian (1963), Bonanza (1963), Dr Kildare (1964) and then Peyton Place (1967-68), which she considered “really fun. They offered me a real ‘Joan Crawford’ bad lady … I came in and married old Mr Peyton and took all the money. I loved it and did it until my unfortunate demise of falling down the grand staircase.”

Rowlands observed: “You have to hand it to television – strangely enough it takes on much more dangerous subjects than movies.” Her TV films included An Early Frost (1985), in which she played the mother of an Aids victim. She won Emmys for her performances in The Betty Ford Story (1987), as the US first lady; Face of a Stranger (1991); Mira Nair’s Hysterical Blindness (2002), which reunited her with Gazzara; and The Incredible Mrs Ritchie (2003), a somewhat dull affair produced by her son to which she lent characteristic gravitas.

In 2009, she was seen in an episode of the TV series Monk, and in 2010 was in NCIS. Two years later she married Robert Forrest, a former businessman.

In 2015 she was awarded an honorary Oscar. Earlier this year, Nick announced that she had been suffering for some years from Alzheimer’s disease.

Rowlands is survived by her three children, Nick, Zoe and Alexandra.

Gena (Virginia Cathryn) Rowlands, actor, born 19 June 1930; died 14 August 2024