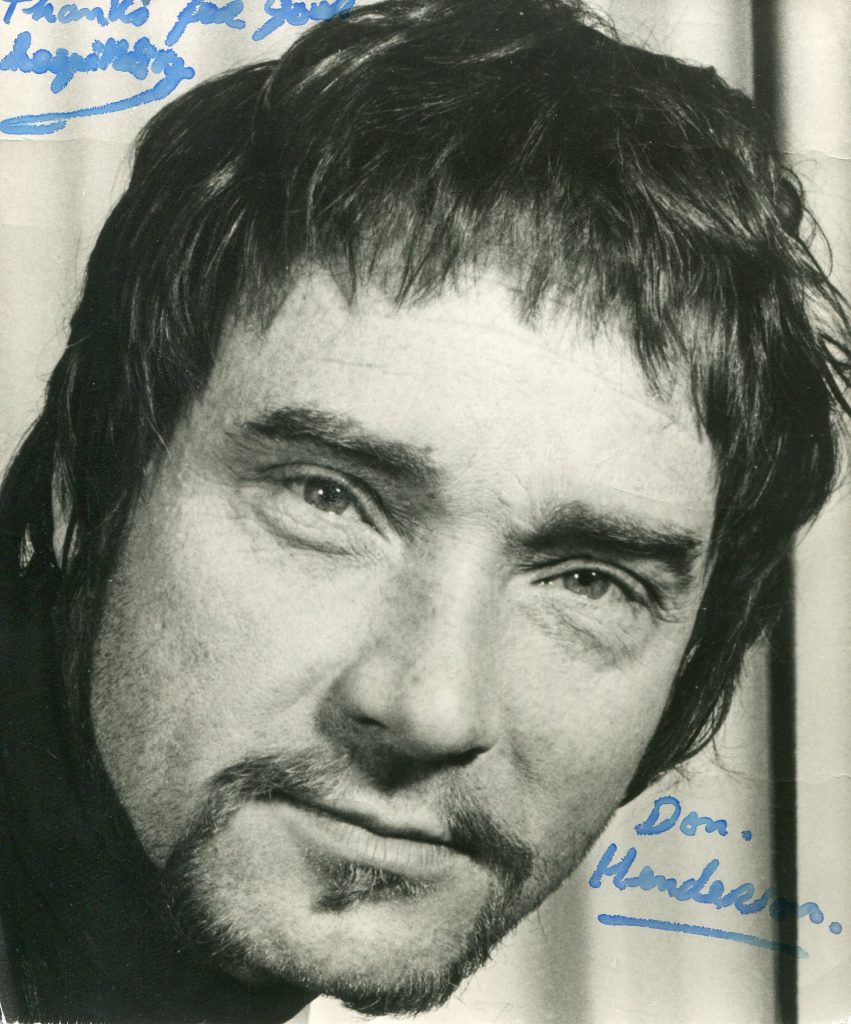

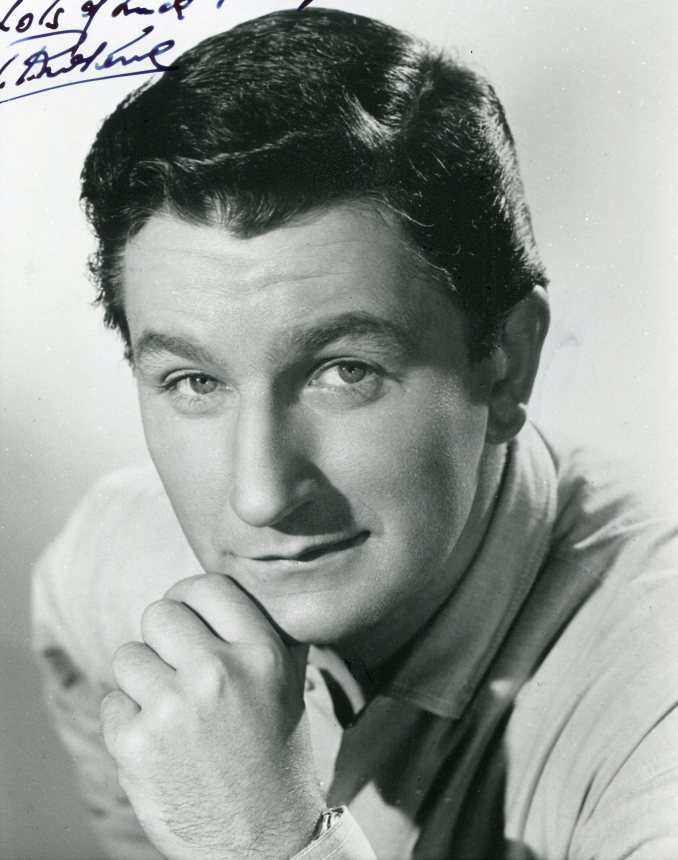

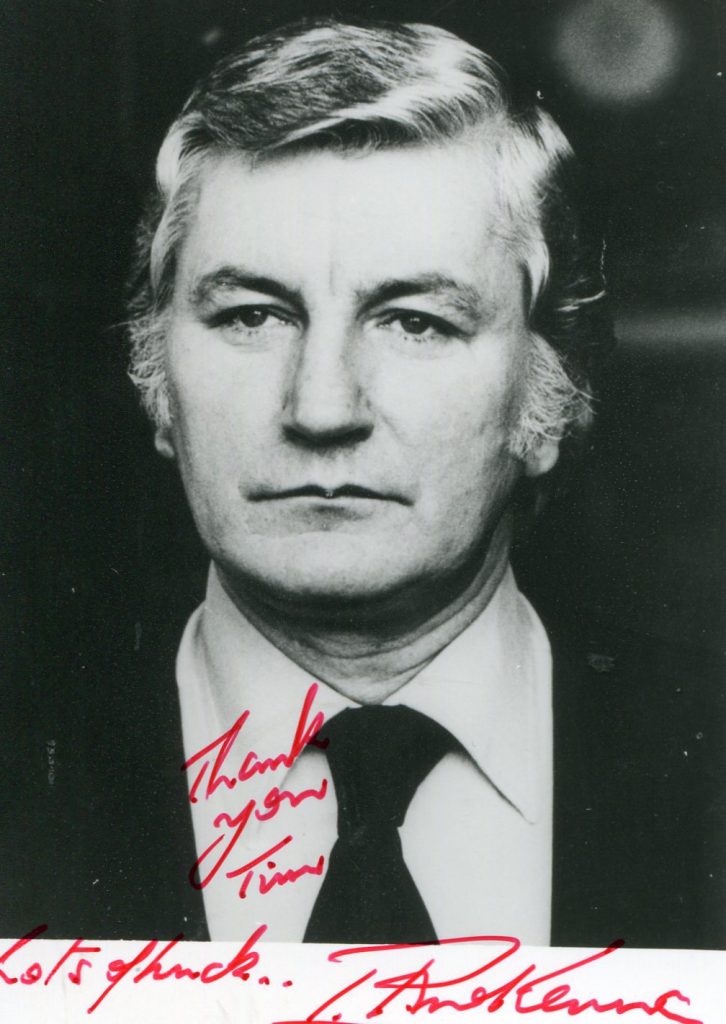

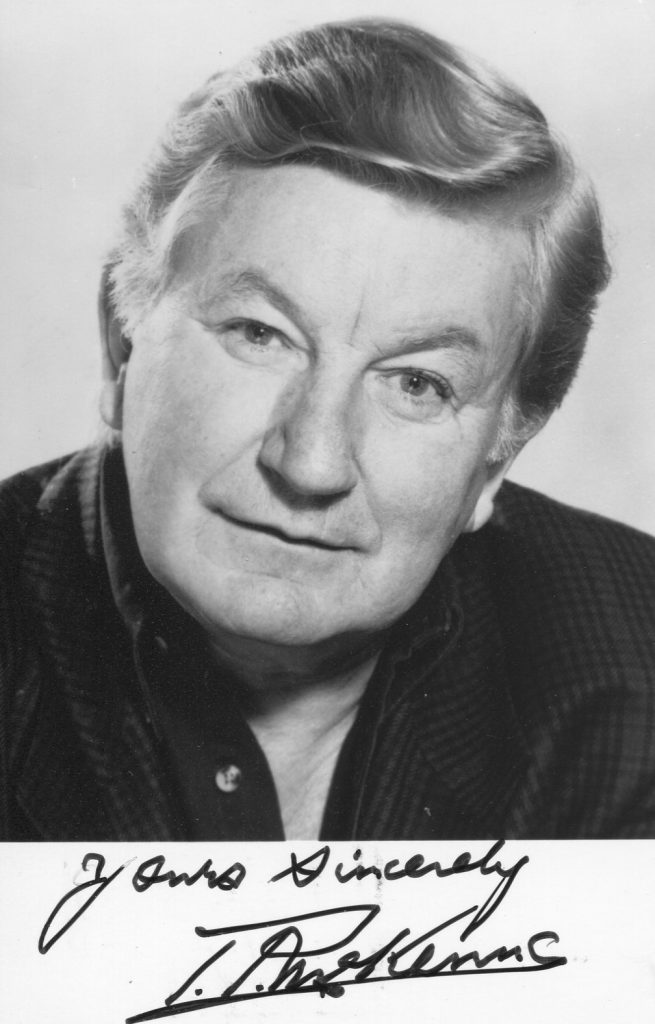

T.P. McKenna was born in 1929 in Co Cavan, Ireland. He began his acting career in Dublin at the famed Abbey Theatre. In 1959 he made the film “Shake Hands With the Devil” with James Cagney, Dana Wynter and Glynis Johns. He made his career in England and acted in most of the major television series of their time e.g.”The Sweeney”. “Blake 7” etc. He died in 2011.

Michael Coveney’s “Guardian” obituary:

Before he became a familiar face on television and cinema screens, the outstanding Irish actor TP McKenna, who has died after a long illness aged 81, bridged the gap between the old and the new Abbey theatres in Dublin. He appeared with the company for eight years during the interim period at the Queen’s theatre; the old Abbey burned down in 1951, the new one opened by the Liffey in 1966.

During that time he made his reputation as a leading actor of great charm, vocal resource – with a fine singing voice – and versatility. He was equally adept at comedy and tragedy, a great exponent of the best Irish playwriting from JM Synge and Séan O’Casey to Hugh Leonard and Brian Friel. The elder son in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night was a favourite, much acclaimed role.

It was Stephen D, Leonard’s skilful conflation of two James Joyce books, for the rival Gate theatre that in 1963 brought McKenna to London, where he stayed for more or less the rest of his career, appearing regularly on West End stages while reaching wider audiences.

He played barristers and detectives, conmen, police officers and a pope. His default mode was an imposing, authoritative geniality, and when he played a Nazi engaging in the casual slaughter of Jews in the TV mini-series Holocaust (1978), it was as hard to watch as it was to credit that this was the same actor who was so delightful as Harold Skimpole (“no idea of time, no idea of money”) in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House (1985) on BBC television.

For an actor, McKenna was an unusually modest and self-effacing man, and this trait lent a profound transparency and poignancy to those performances that touched on failure and disappointment, notably in Chekhov. You never saw the joins.

His family had settled in Mullagh, County Cavan, in the north of Ireland, in the 18th century. His great-grandfather, Nicholas McKenna, was an auctioneer, tradesman and farmer; his uncle, Justin McKenna, a notable politician; and his father, Ralph, also an auctioneer and merchant. Thomas – generally known in later life as “TP” – was the eldest of 10 children. He was educated at Mullagh national school and St Patrick’s college, Cavan, where he studied literature and discovered his acting and singing talent in Gilbert and Sullivan. He played Gaelic football, representing St Patrick’s in the final of the All Ireland colleges competition in 1948.

As a schoolboy, he had seen the legendary Anew McMaster‘s touring company in Shakespeare and decided to go on the stage. But first he took his banking exams in Belfast, then worked for the Ulster Bank in Granard, Trim and Dublin, where he trained at the Abbey Theatre School. He made his debut at the Pyke in 1953, appeared with McMaster at the Gaiety in 1954 (playing Horatio in Hamlet and Albany in King Lear) before joining the Abbey.

McKenna played more than 70 roles for the Abbey at the Queen’s, a large, demanding theatre seating 900. One of the Gate theatre’s biggest modern successes was Stephen D at the Dublin Theatre festival of 1962. In the following year, McKenna came with it, and his fellow actor Norman Rodway, to London. Although he returned to Dublin in 1966 to play in the Abbey’s reopening production – Walter Macken’s Recall the Years, a curtain-raiser to a major revival of O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars – McKenna never liked the new theatre and revelled in the wider opportunities now open to him on British television and stage.

At the Royal Court in 1964, he played Cassius in Lindsay Anderson’s revival of Julius Caesar, then joined Stuart Burge and Jonathan Miller at the Nottingham Playhouse in 1968, playing the Bastard in King John, Joseph Surface in Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The School for Scandal, Trigorin in Chekhov’s The Seagull and Macduff in Macbeth. At the end of an exhausting season, he directed his first and favourite play, Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World.

Back at the Court in 1969, he was one of the two Irish contractors in David Storey’s The Contractor, directed by Anderson, and this role with his compatriot Jim Norton led to both of them being hired by Sam Peckinpah to appear in Straw Dogs (1971), his fourth major film, following Joseph Strick‘s Ulysses (1967) – he was Buck Mulligan – Tony Richardson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), and Charles Jarrott’s Anne of the Thousand Days (1969). McKenna had a soft spot for Peter Hall’s Perfect Friday (1970), a comedy caper with Stanley Baker, Ursula Andress and David Warner, and he also popped up tellingly opposite Richard Burton in Michael Tuchner’s Villain (1971), the first movie “inspired” by the Kray twins.

McKenna had married May White, literally the girl next door, who worked for Radio Éireann, in 1955, but he did not bring the family over to settle in London until 1972. Notable stage roles over the next two decades included Robert Hand in James Joyce’s only play, Exiles, directed byHarold Pinter at the Mermaid in 1970; a straitlaced puritan preacher inGeorge Bernard Shaw‘s The Devil’s Disciple for the RSC in 1976, a performance of coruscating charm opposite Tom Conti, John Wood, Zoë Wanamaker and Bob Hoskins; a beautifully modulated doctor in Max Stafford-Clark’s production of Thomas Kilroy’s take on The Seagull at the Royal Court in 1980; and the Duke of Florence, an acid-voiced, bleakly ruthless intelligencer, in Philip Prowse’s gorgeous staging of John Webster’s The White Devil at the National in 1991.

He returned to the Gate several times. The artistic director Michael Colgan said that his Uncle Vanya there in 1987 was the most moving performance of his tenure, while his Serebryakov in the same Chekhov play, a few years later, fitted equally well. His whiskey-sodden, disenchanted ophthalmologist in Friel’s Molly Sweeney (1994), a play about regaining sight but losing faith, was just as potent and memorable, and he played a wonderful double act with Niall Buggy in Pinter’s No Man’s Land in 1997.

And there seemed hardly a major television series he did not adorn, as a maverick Russian agent in Callan, or as various villains in Lovejoy, Minder and The Sweeney. He was the final suspect ever interviewed byJohn Thaw as Inspector Morse. His last major movie was Lawrence Dunmore’s The Libertine (2004), starring Johnny Depp in Stephen Jeffreys’s screenplay from his own theatre piece, and he last appeared on the London stage in 2005, as the disabled father in a National Theatre revival by Tom Cairns of Friel’s elegiac Aristocrats.

But with a fine, black-humoured Irish flourish, he saved his last gasp for a short, low-budget movie called Death’s Door (2009), in which he played a dying man in a grand old house confronted by a junkie career criminal played by one of the Irish theatre’s rising stars, Karl Sheils.

May died in 2007. McKenna is survived by four sons and a daughter, three brothers and five sisters.

• Thomas Patrick McKenna, actor, born 7 September 1929; died 13 February 2011

The above IMDB entry can also be accessed online here.

T.P. McKenna obituary in “The Guardian”.

T.P. McKenna was born in 1929 in Co Cavan, Ireland. He began his acting career in Dublin at the famed Abbey Theatre. In 1959 he made the film “Shake Hands With the Devil” with James Cagney, Dana Wynter and Glynis Johns. He made his career in England and acted in most of the major television series of their time e.g.”The Sweeney”. “Blake 7” etc. He died in 2011.

Michael Coveney’s “Guardian” obituary:

Before he became a familiar face on television and cinema screens, the outstanding Irish actor TP McKenna, who has died after a long illness aged 81, bridged the gap between the old and the new Abbey theatres in Dublin. He appeared with the company for eight years during the interim period at the Queen’s theatre; the old Abbey burned down in 1951, the new one opened by the Liffey in 1966.

During that time he made his reputation as a leading actor of great charm, vocal resource – with a fine singing voice – and versatility. He was equally adept at comedy and tragedy, a great exponent of the best Irish playwriting from JM Synge and Séan O’Casey to Hugh Leonard and Brian Friel. The elder son in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night was a favourite, much acclaimed role.

It was Stephen D, Leonard’s skilful conflation of two James Joyce books, for the rival Gate theatre that in 1963 brought McKenna to London, where he stayed for more or less the rest of his career, appearing regularly on West End stages while reaching wider audiences.

He played barristers and detectives, conmen, police officers and a pope. His default mode was an imposing, authoritative geniality, and when he played a Nazi engaging in the casual slaughter of Jews in the TV mini-series Holocaust (1978), it was as hard to watch as it was to credit that this was the same actor who was so delightful as Harold Skimpole (“no idea of time, no idea of money”) in Charles Dickens’s Bleak House (1985) on BBC television.

For an actor, McKenna was an unusually modest and self-effacing man, and this trait lent a profound transparency and poignancy to those performances that touched on failure and disappointment, notably in Chekhov. You never saw the joins.

His family had settled in Mullagh, County Cavan, in the north of Ireland, in the 18th century. His great-grandfather, Nicholas McKenna, was an auctioneer, tradesman and farmer; his uncle, Justin McKenna, a notable politician; and his father, Ralph, also an auctioneer and merchant. Thomas – generally known in later life as “TP” – was the eldest of 10 children. He was educated at Mullagh national school and St Patrick’s college, Cavan, where he studied literature and discovered his acting and singing talent in Gilbert and Sullivan. He played Gaelic football, representing St Patrick’s in the final of the All Ireland colleges competition in 1948.

As a schoolboy, he had seen the legendary Anew McMaster‘s touring company in Shakespeare and decided to go on the stage. But first he took his banking exams in Belfast, then worked for the Ulster Bank in Granard, Trim and Dublin, where he trained at the Abbey Theatre School. He made his debut at the Pyke in 1953, appeared with McMaster at the Gaiety in 1954 (playing Horatio in Hamlet and Albany in King Lear) before joining the Abbey.

McKenna played more than 70 roles for the Abbey at the Queen’s, a large, demanding theatre seating 900. One of the Gate theatre’s biggest modern successes was Stephen D at the Dublin Theatre festival of 1962. In the following year, McKenna came with it, and his fellow actor Norman Rodway, to London. Although he returned to Dublin in 1966 to play in the Abbey’s reopening production – Walter Macken’s Recall the Years, a curtain-raiser to a major revival of O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars – McKenna never liked the new theatre and revelled in the wider opportunities now open to him on British television and stage.

At the Royal Court in 1964, he played Cassius in Lindsay Anderson’s revival of Julius Caesar, then joined Stuart Burge and Jonathan Miller at the Nottingham Playhouse in 1968, playing the Bastard in King John, Joseph Surface in Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The School for Scandal, Trigorin in Chekhov’s The Seagull and Macduff in Macbeth. At the end of an exhausting season, he directed his first and favourite play, Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World.

Back at the Court in 1969, he was one of the two Irish contractors in David Storey’s The Contractor, directed by Anderson, and this role with his compatriot Jim Norton led to both of them being hired by Sam Peckinpah to appear in Straw Dogs (1971), his fourth major film, following Joseph Strick‘s Ulysses (1967) – he was Buck Mulligan – Tony Richardson’s The Charge of the Light Brigade (1968), and Charles Jarrott’s Anne of the Thousand Days (1969). McKenna had a soft spot for Peter Hall’s Perfect Friday (1970), a comedy caper with Stanley Baker, Ursula Andress and David Warner, and he also popped up tellingly opposite Richard Burton in Michael Tuchner’s Villain (1971), the first movie “inspired” by the Kray twins.

McKenna had married May White, literally the girl next door, who worked for Radio Éireann, in 1955, but he did not bring the family over to settle in London until 1972. Notable stage roles over the next two decades included Robert Hand in James Joyce’s only play, Exiles, directed byHarold Pinter at the Mermaid in 1970; a straitlaced puritan preacher inGeorge Bernard Shaw‘s The Devil’s Disciple for the RSC in 1976, a performance of coruscating charm opposite Tom Conti, John Wood, Zoë Wanamaker and Bob Hoskins; a beautifully modulated doctor in Max Stafford-Clark’s production of Thomas Kilroy’s take on The Seagull at the Royal Court in 1980; and the Duke of Florence, an acid-voiced, bleakly ruthless intelligencer, in Philip Prowse’s gorgeous staging of John Webster’s The White Devil at the National in 1991.

He returned to the Gate several times. The artistic director Michael Colgan said that his Uncle Vanya there in 1987 was the most moving performance of his tenure, while his Serebryakov in the same Chekhov play, a few years later, fitted equally well. His whiskey-sodden, disenchanted ophthalmologist in Friel’s Molly Sweeney (1994), a play about regaining sight but losing faith, was just as potent and memorable, and he played a wonderful double act with Niall Buggy in Pinter’s No Man’s Land in 1997.

And there seemed hardly a major television series he did not adorn, as a maverick Russian agent in Callan, or as various villains in Lovejoy, Minder and The Sweeney. He was the final suspect ever interviewed byJohn Thaw as Inspector Morse. His last major movie was Lawrence Dunmore’s The Libertine (2004), starring Johnny Depp in Stephen Jeffreys’s screenplay from his own theatre piece, and he last appeared on the London stage in 2005, as the disabled father in a National Theatre revival by Tom Cairns of Friel’s elegiac Aristocrats.

But with a fine, black-humoured Irish flourish, he saved his last gasp for a short, low-budget movie called Death’s Door (2009), in which he played a dying man in a grand old house confronted by a junkie career criminal played by one of the Irish theatre’s rising stars, Karl Sheils.

May died in 2007. McKenna is survived by four sons and a daughter, three brothers and five sisters.

• Thomas Patrick McKenna, actor, born 7 September 1929; died 13 February 2011

The above IMDB entry can also be accessed online