“Valerie Hobson was- to her disadvantage- ineffably ladylike. The British film industry of the 30s and 40s was a man’s world and the female stars got short shrift. Those British stars who did go to Hollywood were criticized back home for resubmitting to that town’s despised glamour treatment. Hobson’s time in Hollywood was not at all worthwhile, and she might have made no stronger mark in the British industry had not she managed to assert her distinctive personality from time to time. ” – David Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars” (1970)

Valerie Hobson obituary in “The Guardian” in 1998.

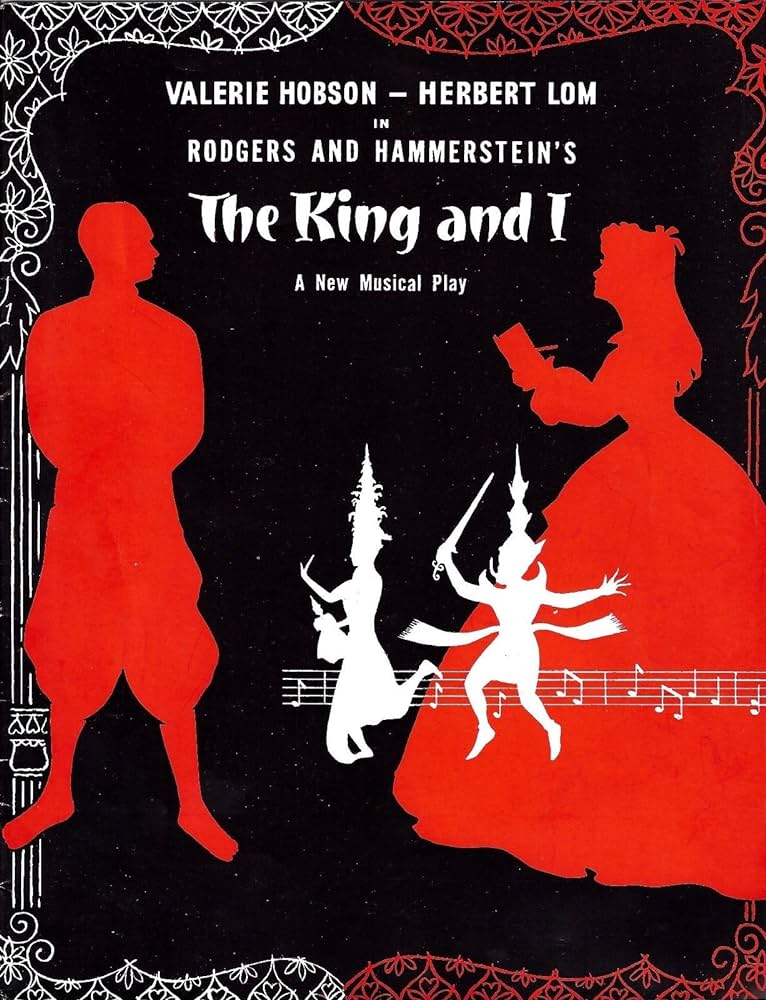

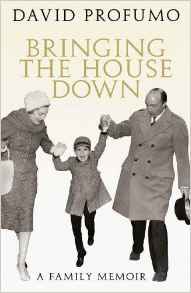

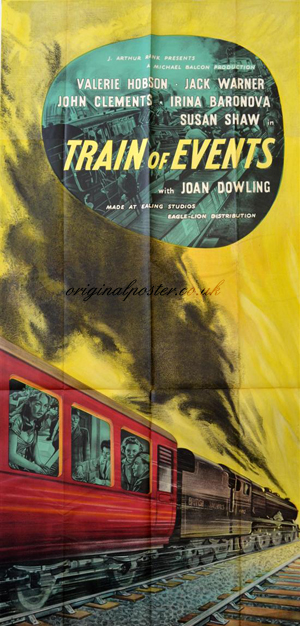

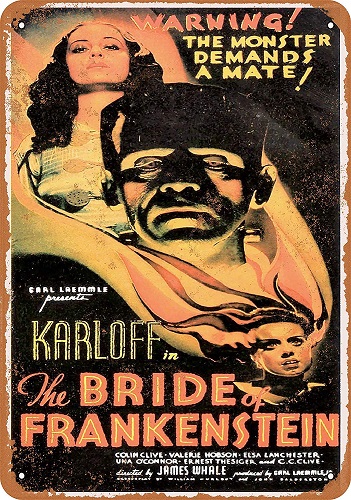

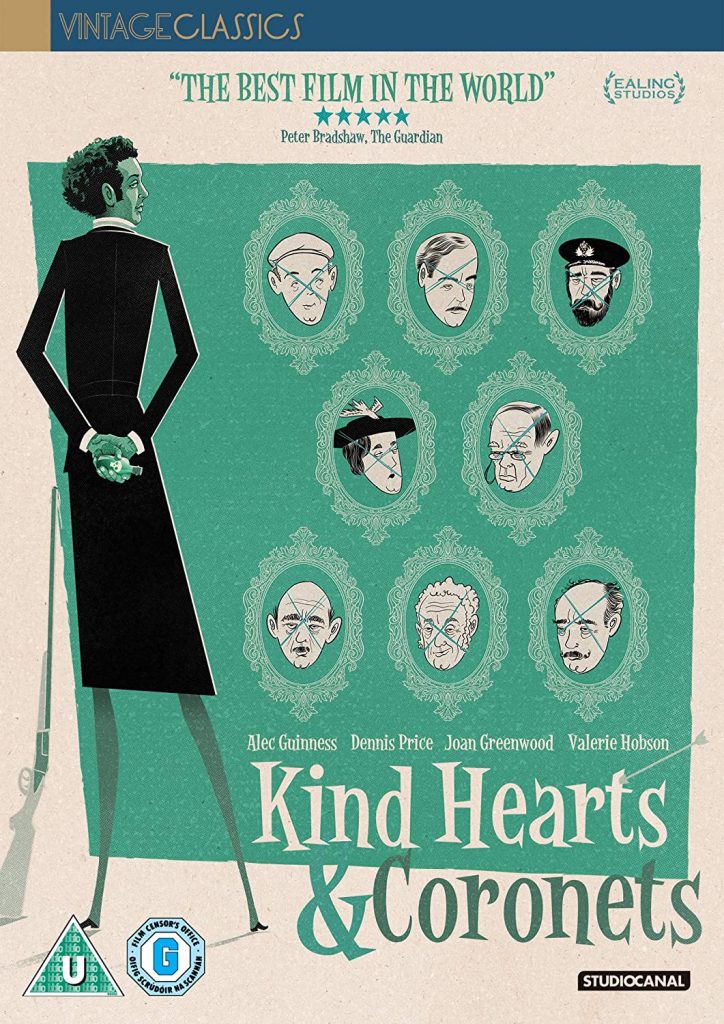

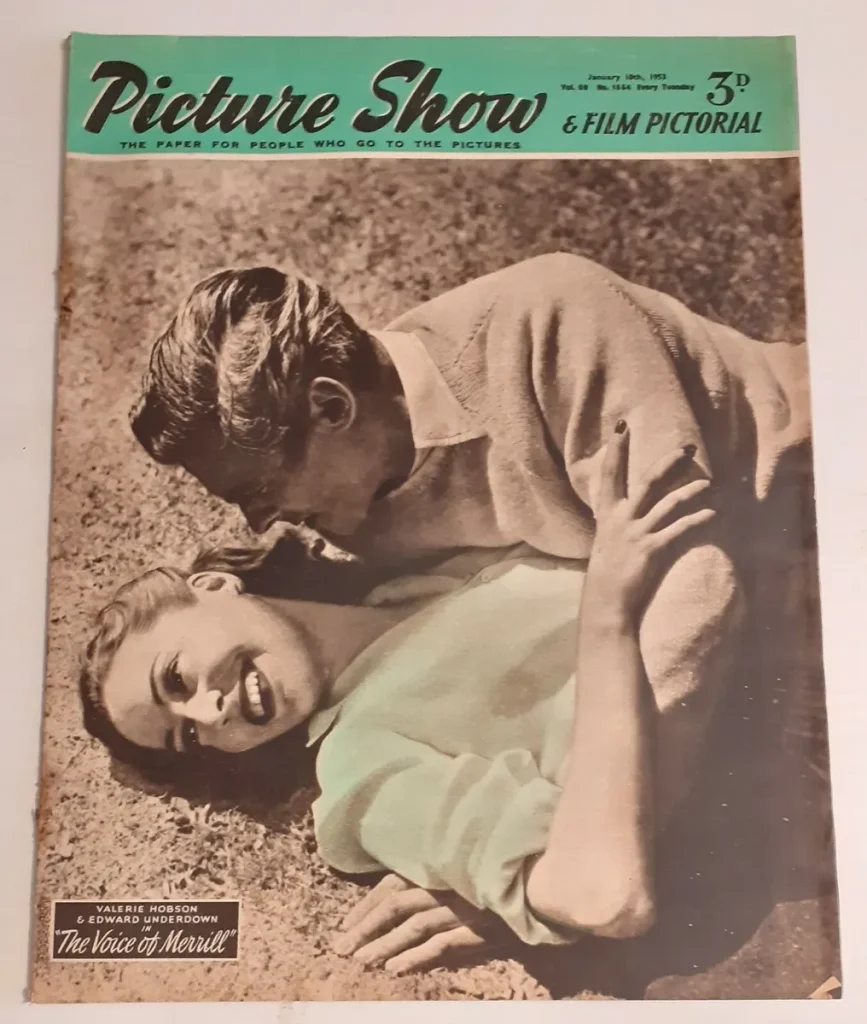

Valerie Hobson has two distinct phases to her acting career. She was born in 1917 in Larne in Northern Ireland. She started her career in British films but by 1935 when she was only 18 she was acting in Hollywood. She starred in two classic Universal horror movies “”The Werewolf of London” and the magnificent James Whale directed “The Bride of Frankenstein” with Boris Karloff and Colin Clive. By the late thirties she was back in Britain and and continued her career there. Her second period of fame was with a series of films she made from the mid 1940’s onwards in the U.K. including David Lean’s “Great Expectations”, “KInd Hearts and Coronets”, “The Years Between” and “The Card”. In 1954 after a period playing Mrs Anna in the West End production of “The KIng and I”, Valerie Hobson retired from acting. Her name came into the headlines nine years later when her husband MP, John Profumo got involved in a scandal with Russian diplomats and Christine Keeler. Valerie Hobson and John Profumo remained together and weathered the storm and spent their remaing years involved in many charitable causes especially in the East End of London. She died in 1998 at the age of 81. Her son David has written a terrific book about his remarkable parents entitled “Bringing the House Down” which was published in 2006.

“Independent” obituary by Tom Vallance:LIKE MANY British female film stars of the Thirties and Forties, Valerie Hobson exuded breeding and class, but she also brought to her performances a delightfully sophisticated sense of humour and a refreshing element of spunk, whether as the wise-cracking heroine of Q Planes, the resourceful double agent of The Spy in Black, the haughty Estella of Great Expectations, the shrewd widow in Kind Hearts and Coronets, or, on stage, the dignified but determined governess Anna Leonowens in The King and I.

She was to display similar grit in her real life when her husband, the politician John Profumo, became notorious for his relationship with a call-girl who was also involved with a Russian official. In an admirable display of stoicism and loyalty, Hobson stood by her husband and they were to remain married until her death.

She was born Valerie Babette Louise Hobson, in Larne, Northern Ireland, in 1917, the daughter of a British naval officer who was serving on a minesweeper at the time. She was educated at St Augustine’s Priory, London and started dancing lessons at three:

When we moved to Hampshire and I was five, I was taken to London twice a week to be taught ballet by Espinosa. These lessons were intended to “give me grace”, but were precious training for the stage, which I’d been heading for ever since I grabbed a bath towel and pretended to be the Queen of Sheba, with nanny for an audience.

After training at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, she made her stage debut at the age of 15 in Orders Are Orders. Oscar Hammerstein II, who saw her in the show, spotted her lunching with her mother at Claridge’s, went over to their table and offered her a small part in his production Ball at the Savoy, starring Maurice Evans, at Drury Lane. While appearing in the show, she made her first film, a minor thriller Eyes of Fate (1933).

Evans then asked her to appear with himself and Henry Daniell in the film version of L. DuGardo Peach’s radio play The Path of Glory (1934), a satire on war so biting that it was taken out of distribution after one day. Hobson had a small stage role in Noel Coward’s Conversation Piece, during the run of which she played the romantic lead in a popular screen adaptation of R.C. Sherriff’s play Badger’s Green. As the daughter of a developer whose plans will wreck a village’s beloved cricket green, she complicates things by falling in love with the son of a protestor.

Her performance in the film led to tests for Hollywood and the offer of a contract by Universal Pictures. With her mother, the 17-year-old Hobson departed for the US, but was disappointed with the parts she was given. Ironically her first role, that of Biddy in the studio’s version of Dickens’ Great Expectations (1934) was eliminated from the final print – years later Hobson was to have notable success as Estella in David Lean’s masterly version of the same tale.

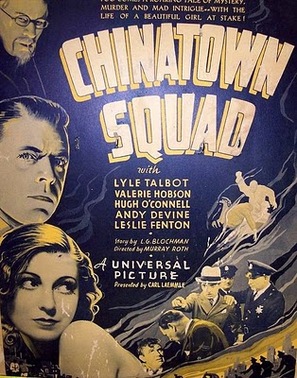

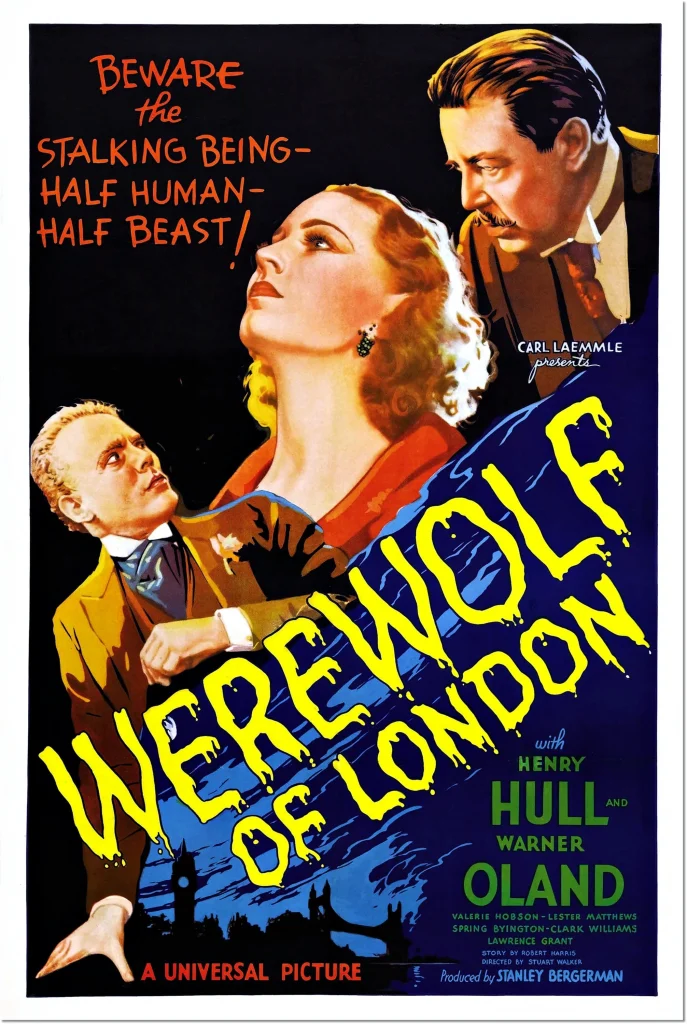

The studio started her in B films (briefly as a platinum blonde), and though one of Hobson’s subsequent American films is a true classic, James Whale’s baroque Bride of Frankenstein (1935), the actress was unhappy with the other horror films and minor thrillers she was offered. Even in the best, The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1935) and Werewolf of London (1935), her roles were colourless. “I’d been there 18 months and learnt a great deal, but I was getting tired of horror pictures and doing nothing but scream and faint . . . In The Bride of Frankenstein, I was

carried by Boris Karloff over almost every artificial hill in Hollywood.” Universal in fact kept her screams in their sound library to use in subsequent horror movies.

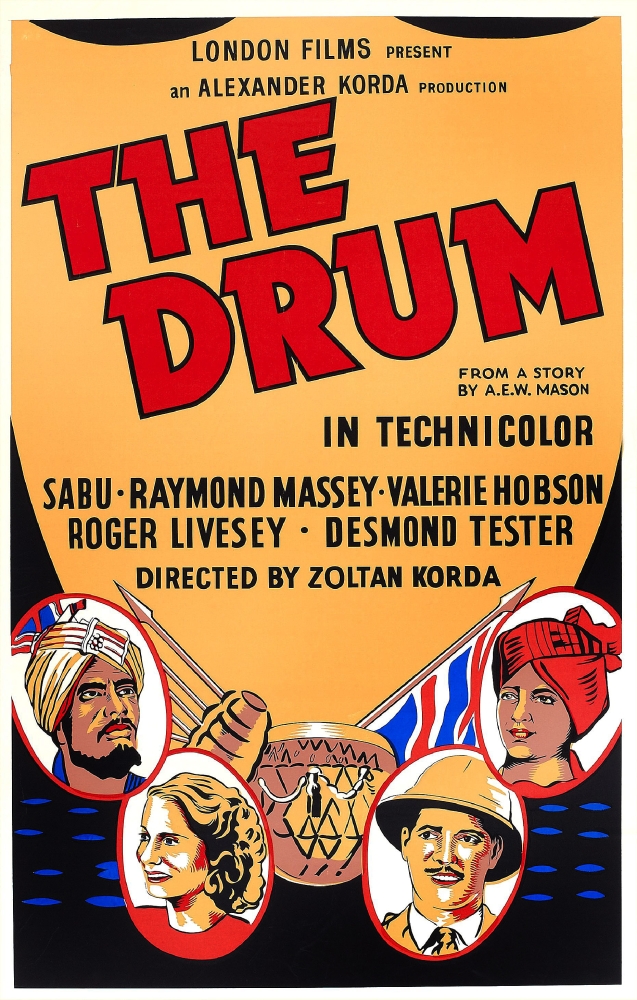

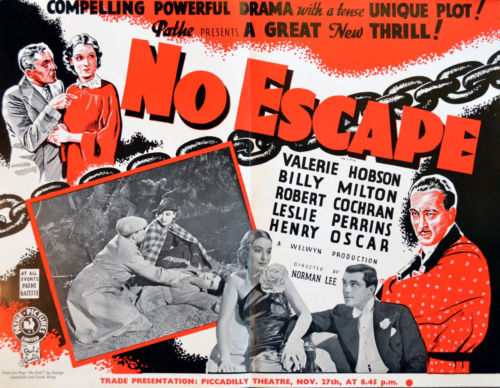

Hobson returned to England in 1936, where in such films as the intriguing thriller No Escape (1936) she quickly established herself as a stylish leading lady. In this pre-war period Hobson reputedly also made more television appearances than any other actress. The producer Alexander Korda, after seeing Hobson’s performance opposite Douglas Fairbanks Jr in Raoul Walsh’s Jump For Glory (1937), tested her for the role of a colonel’s wife on the North West Frontier in his production The Drum (1938).

Her next film, the comedy-thriller This Man Is News (1938), was the first to display Hobson’s innate flair for comedy and was favourably compared by critics to America’s “Thin Man” films, with Hobson and Barry K. Barnes as a pair of wise-cracking, cocktail-drinking married sleuths. “It had an extraordinary success,” Hobson told Brian McFarlane a few years ago. “As a nation we hadn’t made a high comedy successfully until then. When they put it on at the Plaza there were queues literally round the block to see it.”

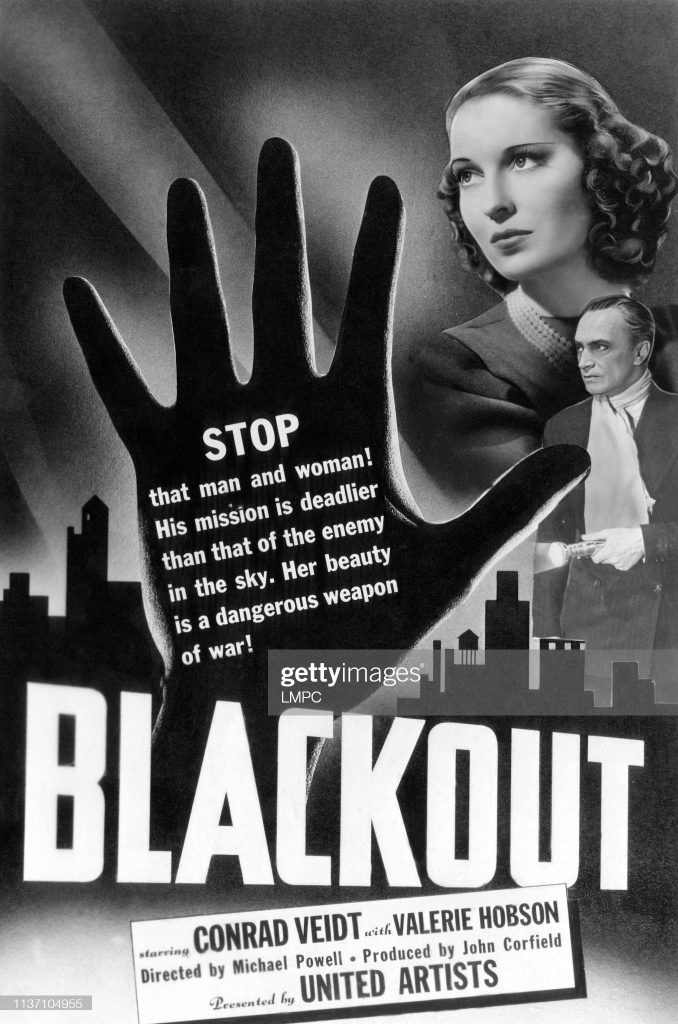

A sequel, This Man in Paris (1939), was even better than the first. Both films were produced by Anthony Havelock-Allan, with whom Hobson fell in love, and they were married in 1939. Meanwhile the Korda production Q Planes (1938) had consolidated Hobson’s stardom. As the sister of Ralph Richardson and sweetheart of Laurence Olivier, Hobson brought infectious sparkle to a lively and witty espionage thriller, and she followed this with two more highly entertaining thrillers, The Spy in Black (1939) and Contraband (1940), both co- starring Conrad Veidt, scripted by Emeric Pressburger and directed by Michael Powell, who was to recall, “Valerie was a tall, strong, intelligent girl with glorious eyes and a quick wit (too quick a wit, some people thought, but I had suffered too many English ladies to complain about that).”

The Spy in Black opened in London the week that war was declared, was a great hit in both England and the US, and prompted the second pairing of the two stars in Contraband, aptly retitled Blackout in the US since a great deal of the film’s action takes place in a blacked-out West End. During the war years Hobson’s career faltered after she turned down David O Selznick’s offer of a Hollywood contract because she did not want to leave her husband.

She was off screen for three years after The Adventures of Tartu in 1943, and other actresses became more popular, notably those of the Gainsborough pictures, such as Margaret Lockwood, Phyllis Calvert, Jean Kent and Patricia Roc, all of whom could play earthier roles than Hobson, who was becoming increasingly patrician.

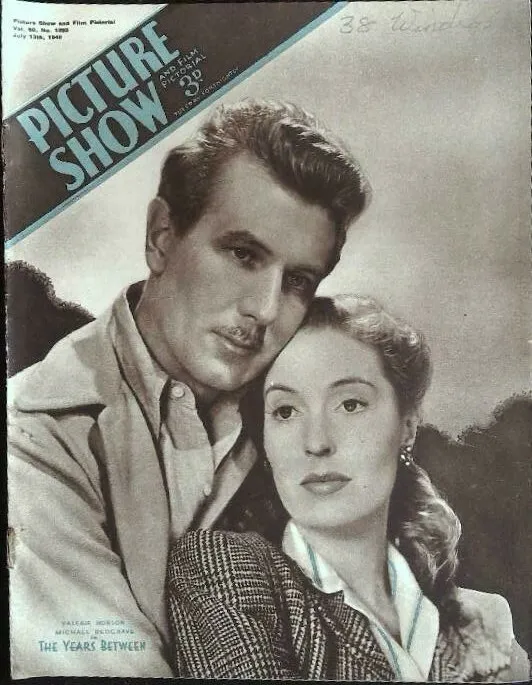

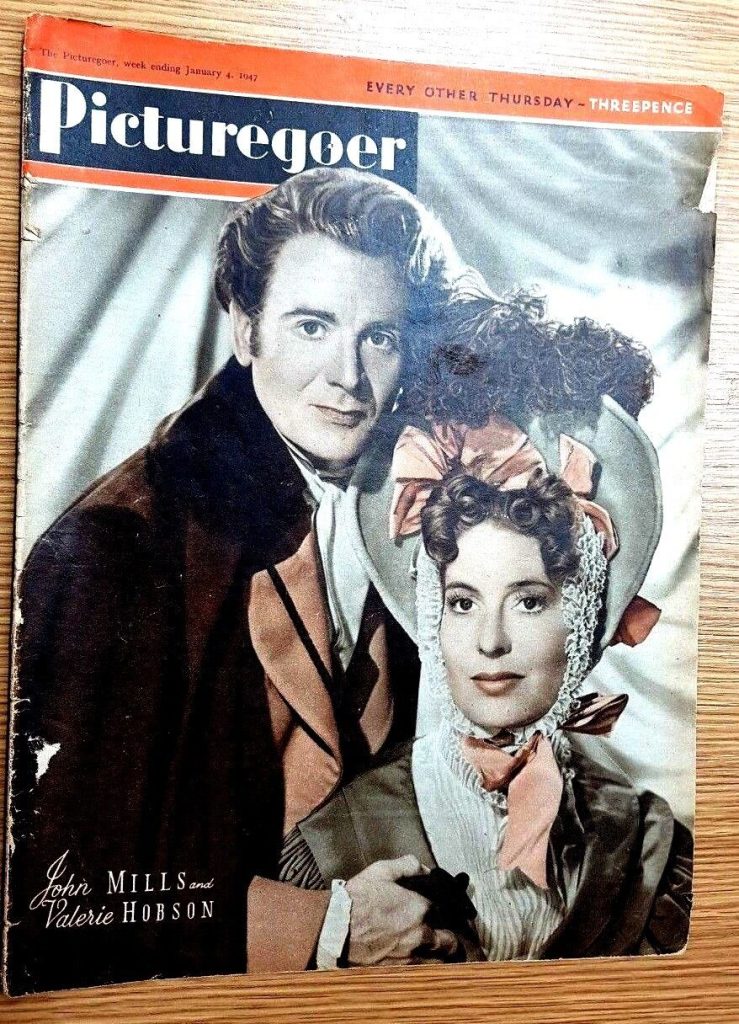

She returned to the screen as an MP who finds it difficult to adjust to life with a husband returned from the war in The Years Between (1946), then was cast as Estella in Great Expectations (1946), regarded by many as the finest screen adaptation of a Dickens novel. The film was produced by Cineguild, a company formed by Hobson’s husband along with Ronald Neame and David Lean, and the same group produced Hobson’s next film, a lavish costume melodrama Blanche Fury (1947).

In this gloomy tale, Stewart Granger was the illegitimate but rightful heir to the Fury estate who murders Hobson’s husband and father-in-law. He is hanged for his crimes and Hobson dies giving birth to his son. An attempt to appeal to the audience who had flocked to Gainsborough melodramas, it was too sombre for popular acceptance. Said Hobson, “I had just had our son, who was born mentally handicapped, and Tony meant the film as a sort of `loving gift’, making me back into a leading lady.”

The film’s beautiful production values and stunning colour photography prompted critic Richard Winnington to comment: “Let’s have some bad lighting and some bad photograph and perhaps a bit of a good movie.” More highly thought of today, the film remains Hobson’s own favourite.

In 1949 she starred in a film unanimously praised as a classic comedy, Robert Hamer’s Kind Hearts and Coronets. Hobson stated:

I have always thought that the main reason for the success of Kind Hearts was that it was played absolutely dead straight. I think they were very clever and cast two such contrasting types as Joan Greenwood and myself as the women.

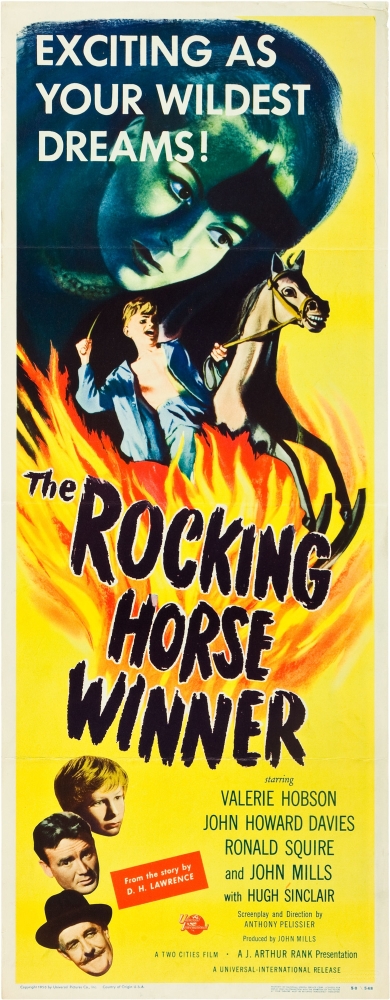

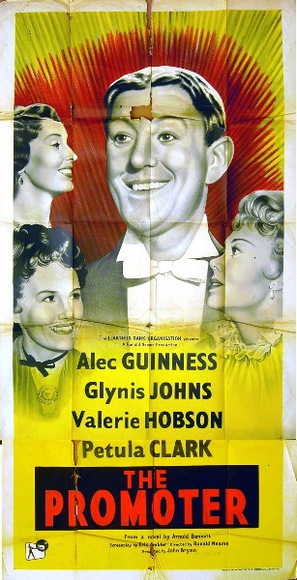

Hobson had an unsympathetic role as a selfish mother in The Rocking Horse Winner (1948) and played the Countess in The Card (1951), again co-starring with Alec Guinness (“a wonderful film actor with the most subtle integrity”). In 1952 she and Havelock-Allan were divorced.

Good film roles were becoming scarce again when Hobson was offered the starring role of Anna in the Drury Lane production of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical The Kind and I. The show’s original Broadway star, Gertrude Lawrence, had planned to recreate her part in London prior to her untimely death. (Hobson had studied singing at RADA, and during her Hollywood stay had sung on Bing Crosby’s radio programme.)

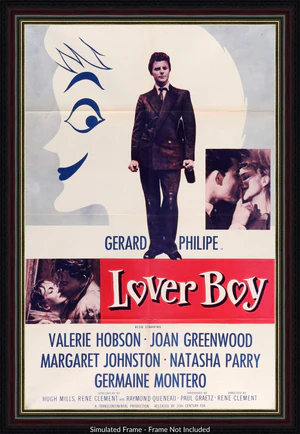

With Herbert Lom playing the King the show was a smash hit and a great personal success for Hobson. It opened in October 1953 and Hobson stayed in it for a year and a half, announcing that at the end of the run she would retire since she doubted anything in her career could top this. Her last film was Rene Clement’s witty comedy, Knave of Hearts (Monsieur Ripois) (1954) in which she was the accommodating wife of a philanderer (Gerard Philipe). She had married an MP, John Profumo, and stated that she would devote the rest of her life to being his wife.

When in March 1963 her husband admitted his affair with Christine Keeler and resigned from his post as Secretary of State for War, Hobson’s name was again in the headlines. “Of course I am not leaving Jack because this ghastly thing has happened,” she said at the time. “I hope to spend the rest of my life with him and my family – the rest of my life.” She continued to deal with the matter with restraint and dignity but did not flinch from the facts.

A few weeks after the headlines dozens of reporters and photographers rushed to Dymchurch in Kent where Hobson was making her first public appearance since the scandal, opening a home for mentally handicapped children. Before the ceremony, she told the crowd of over 1,000 people:

I hope you will forgive me if I start on a more private note. The personal affairs of my family have been so greatly in the limelight recently that it has not been quite easy for me to decide whether or not I should have fulfilled this engagement. The invitation which I accepted with great joy last October, has turned out to be a little of an ordeal. But when I see you all and know how friendly and kind you always are I know that, in fact, it is one of my great joys. There are occasions when all personal circumstances come secondary.

At the end of the ceremony the actress received a prolonged ovation. Her involvement with the mentally handicapped started after one of her two sons by Havelock-Allan was born with Downs Syndrome and she also devoted time to Lepra, a leprosy relief organisation. John Profumo, after his resignation, worked tirelessly for charity, notably at Toynbee Hall, a welfare organisation for the poor and victims of alcohol and drugs, and his wife assisted him in this. In 1975 he was appointed Commander of the British Empire and Hobson, who accompanied him to Buckingham Palace, made evident her great pleasure that her husband’s public service had been recognised.

Tom Vallance

Valerie Babette Louise Hobson, actress: born Larne, Co Down 14 April 1917; married 1939 Anthony Havelock-Allan (one son and one son deceased; marriage dissolved 1952), 1954 John Profumo (one son); died London 13 November 1998.

This “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

TCM Overview:

Upper-crust beauty who established herself on the British stage and made her film debut in “Moulin Rouge” (1952). Bennett appeared in several plays written by her then-husband John Osborne, including “A Patriot for Me”, “Watch It Come Down” and “Time Present,” for which she won the London Evening Standard Award and Variety Club of Britain awards

Dictionary of Irish Biography:

Hobson, Valerie (1917–98), actress, was born 14 April 1917 at Larne, Co. Antrim, daughter of Commander Robert Gordon Hobson (1877–1940), naval officer, and Violette Hobson (née Hamilton-Willoughby). Educated at St Augustine’s Priory, London, she was stage-struck from a young age. Starting ballet at three, she was taught by Espinosa in London from the age of five. However, she was too tall to be a ballerina and settled instead on acting, enrolling in RADA. Her stage debut, at the age of 15, was in Basil Foster’s ‘Orders are orders’, where she was spotted by Oscar Hammerstein, who cast her in his West End show ‘Ball at the Savoy’ in Drury Lane. This showcased her talents as a comedienne and led to a series of appearances in British B movies, including Two hearts in waltz time, The path to glory, and Badger’s Green, all in 1934. Still a minor, she had to be accompanied to the studio by her nanny. At 18 she won a contract with Universal Studios; however, Hollywood proved a disappointment. After appearing in a succession of farces and thrillers, of which only The bride of Frankenstein (1935) is remembered, she fell victim to the reorganisation of the studios in the mid 1930s, following a financial crisis, and her contract was not renewed, though her marked prowess as a screamer meant that Universal filed her top decibels in the studio sound library.

Back in England she was cast opposite Douglas Fairbanks, jr, in Jump for glory (1937), in which she caught the eye of Alexander Korda, who signed her to a long-term contract. She made, however, only two films for Korda: The drum (1938), about the North-West Frontier, and Q planes (1939) with Ralph Richardson and Laurence Olivier. During this period she also worked twice for Michael Powell: in The spy in black (1939) and Contraband(1940), both with Conrad Veidt. In 1939 she married Anthony Havelock-Allan, her former co-star in Badger’s Green and now a producer. Three years later she was offered a second Hollywood contract by David O. Selznick, who wanted her for Jane Eyre. However, with the war at its height she was unwilling to leave her husband. He subsequently founded, with David Lean and Ronald Neame, the Cineguild production company, of which he was eventually head. Cineguild provided Hobson with some of her strongest roles, including Estella in David Lean’s Great expectations (1946) and the title role in Blanche Fury (1948), a period melodrama with Stewart Granger. Excellent as Estella, a part that suited what the Daily Telegraph (14 Nov. 1998) called the ‘slightly smug, lecturing strain in her on-screen personality’, she was not in general convincing as the love interest. Although beautiful, with long auburn hair, she was upper-crust and aloof and seemed too prim and ladylike to appear opposite matinée idols such as Granger and Gérard Philippe.

Havelock-Allan left Cineguild in 1947, taking Hobson with him. Together they made The small voice (1948), about an ordinary family held to ransom by escaped convicts. Her subsequent career consisted of minor melodramas and comedies, of which the most celebrated is Kind hearts and coronets (1949) opposite Alec Guinness. The part of the prudish, aristocratic Edith D’Ascoyne suited her talents perfectly, as did that of the governess in the Rogers and Hammerstein musical ‘The king and I’, which she played in Drury Lane in 1953 after a long absence from the stage. Though not musically trained, she made a success of the part and the play ran for a year. Remarking that she was unlikely to be offered as good a role again, she retired at the age of 37. Her last screen appearance was in Knave of hearts (1954). That year she married (31 December) the wealthy tory MP for Stratford (1950–63), Jack Profumo, having divorced Havelock-Allan in 1952.

A life as socialite, MP’s wife, and mother was disrupted by the ‘Profumo scandal’ of 1963. Her husband, secretary of state for war since 1960, denied in the house of commons (22 March 1963) having had an affair with Christine Keeler, the lover of a Soviet official. Subsequently proved to have lied, he had to resign both from his ministry and his seat three months later. Hobson told Lord Denning, who conducted an inquiry, that stress, exhaustion, and sleeping pills contributed to her husband’s making his false statement to the commons. She stood by him and joined him in his later career as charity worker. He established the Toynbee Hall centre in east London for people experiencing alcoholism and drug addiction (for which he received a CBE in 1975) while she put her energy into working for children with intellectual disabilities (with whom she had an affinity, as her eldest son from her first marriage had Down’s syndrome). For Lepra, a leprosy relief organisation, she dreamed up the ‘ring appeal’, which encouraged wealthy people, including members of the royal family, to hand over rings to raise money. She died 13 November 1998 in England, and was survived by both husbands and a son from each marriage: Mark Havelock-Allan and the writer David Profumo