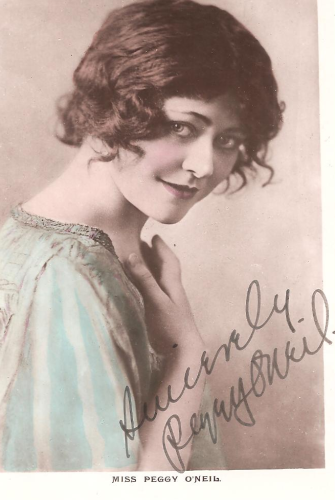

Peggy O’Neil was born in New York in 1894 and died in London in 1960. Her film career was based mainly in the U.S. and her stage career in Britain.

Hollywood Actors

Peggy O’Neil was born in New York in 1894 and died in London in 1960. Her film career was based mainly in the U.S. and her stage career in Britain.

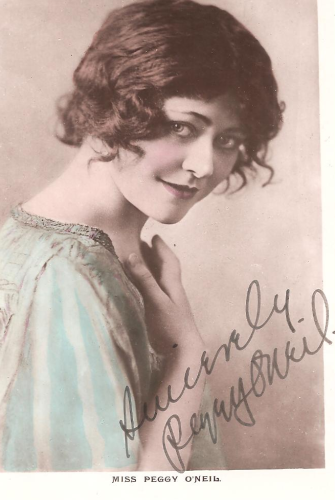

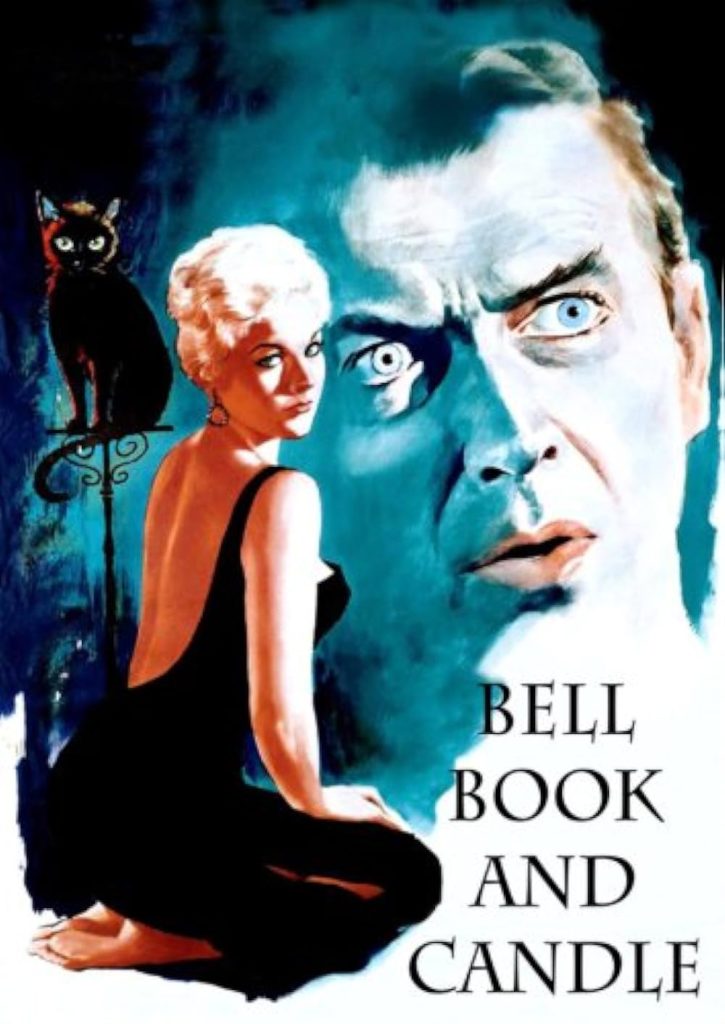

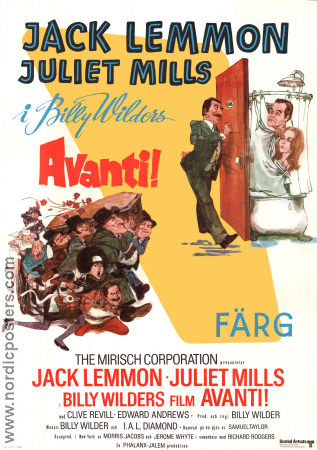

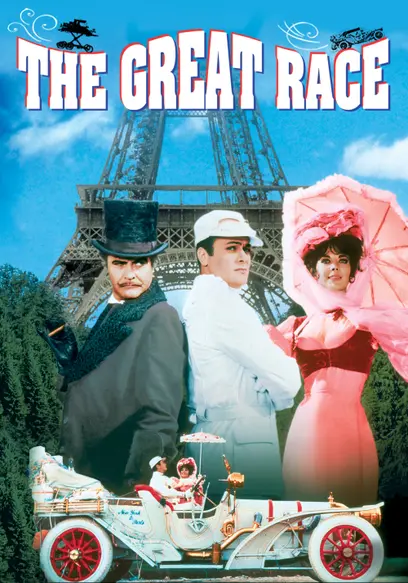

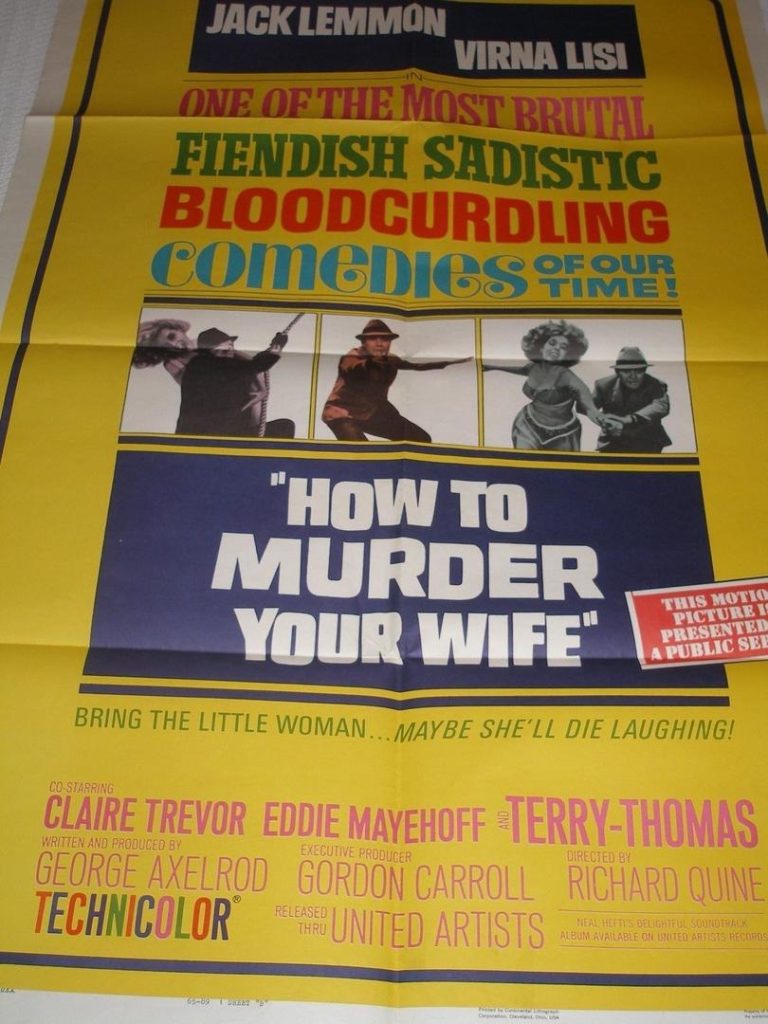

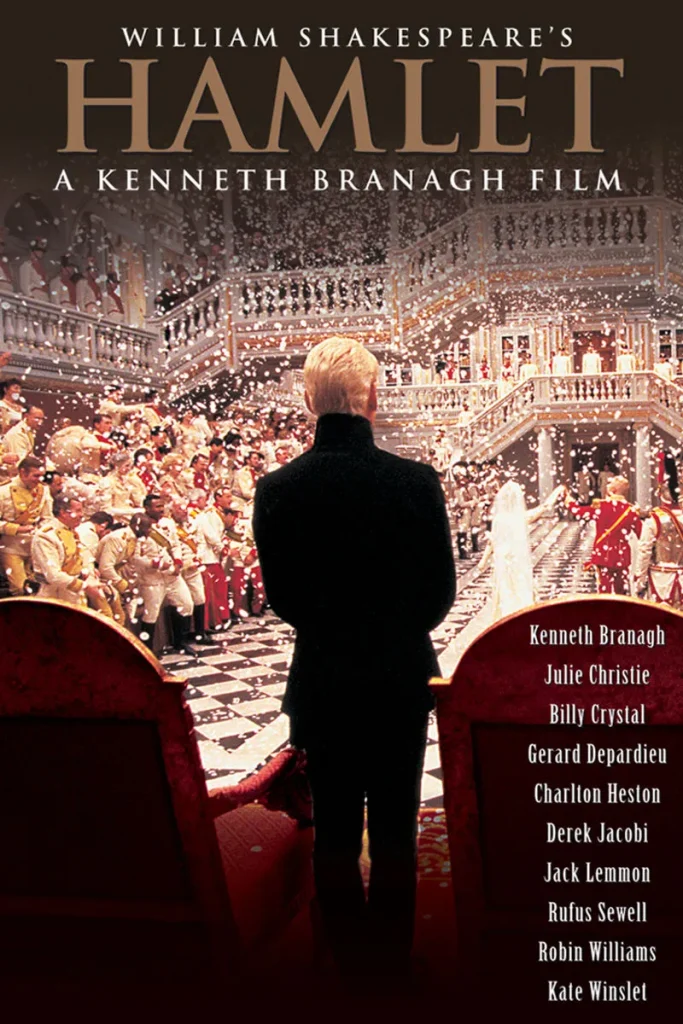

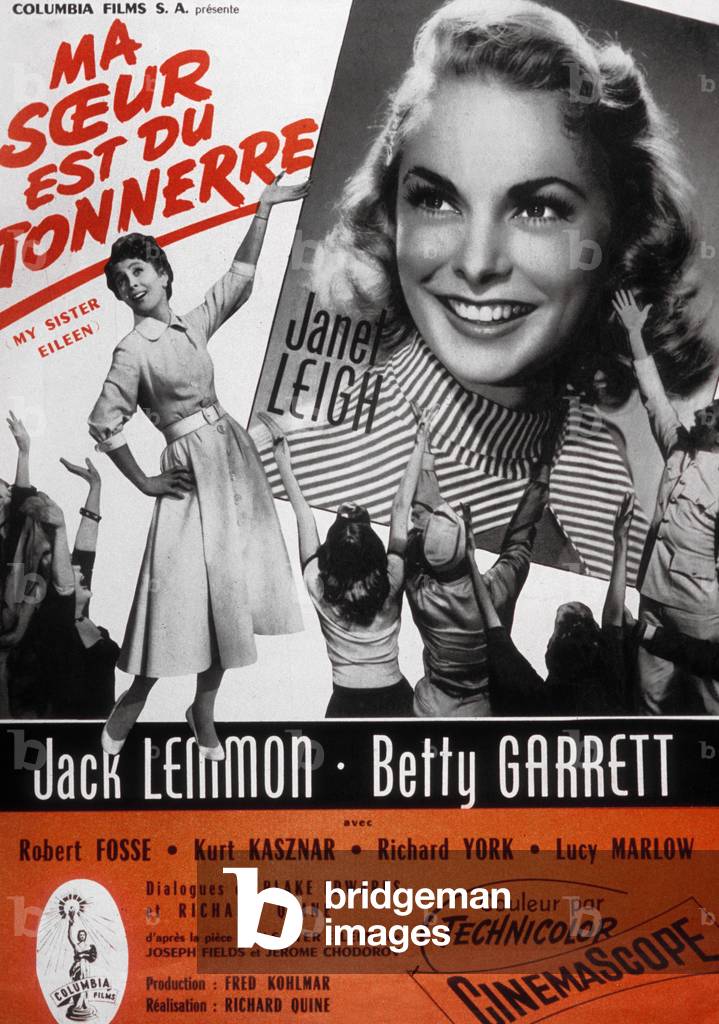

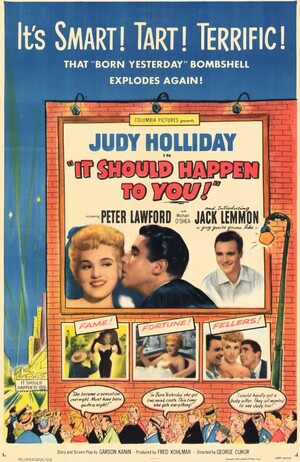

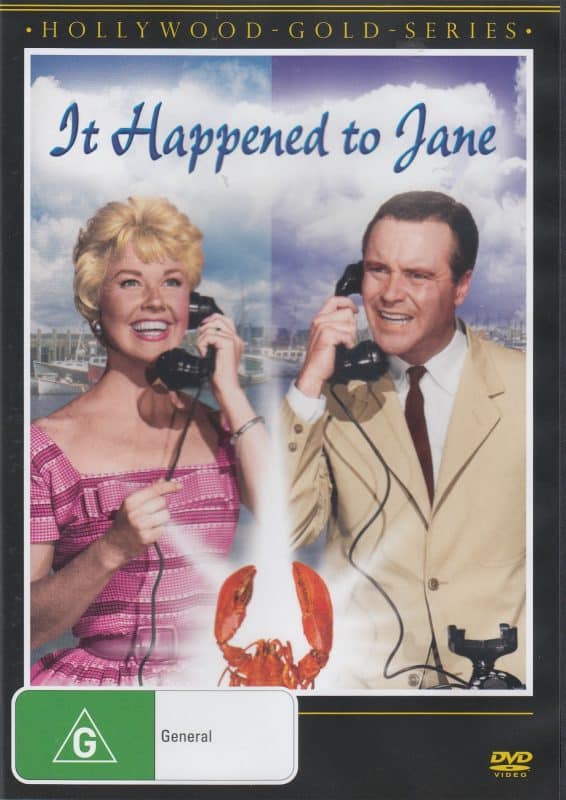

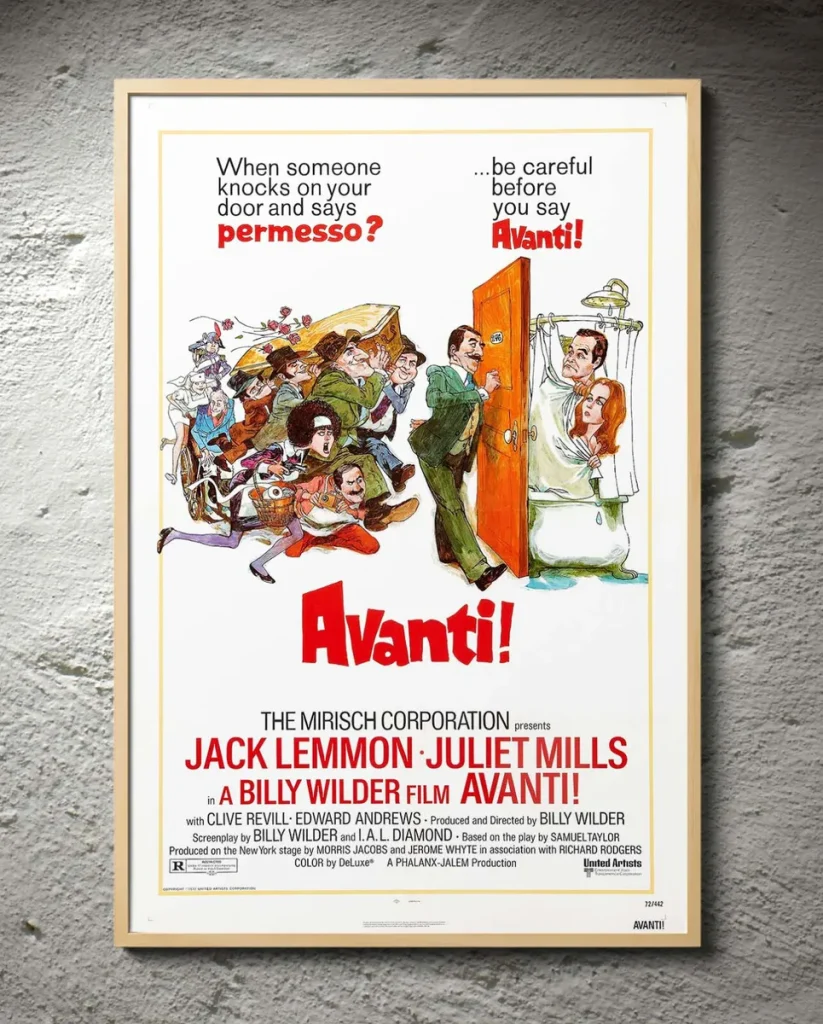

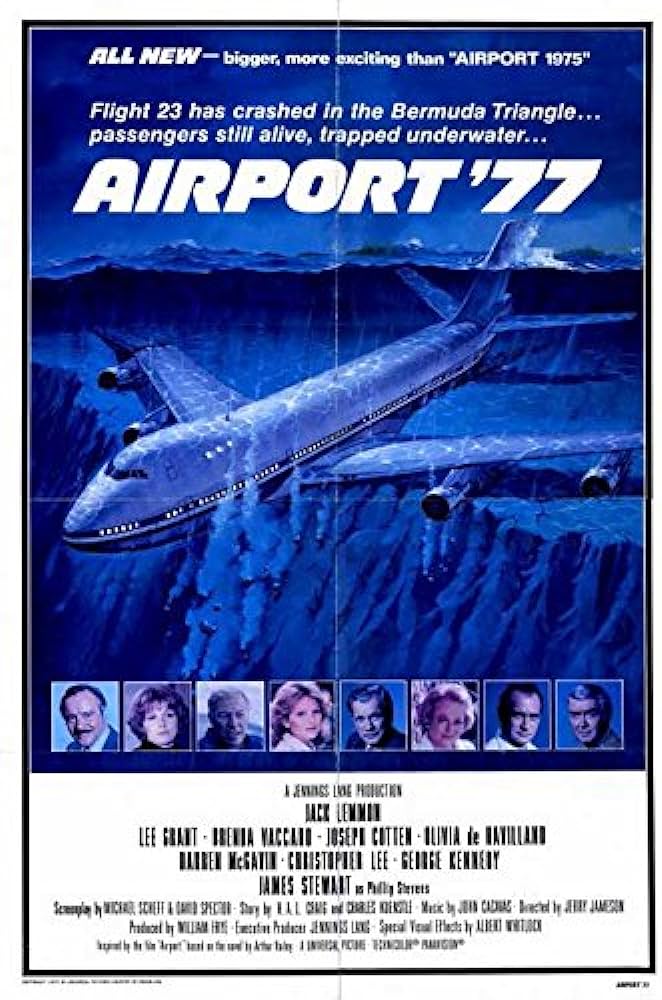

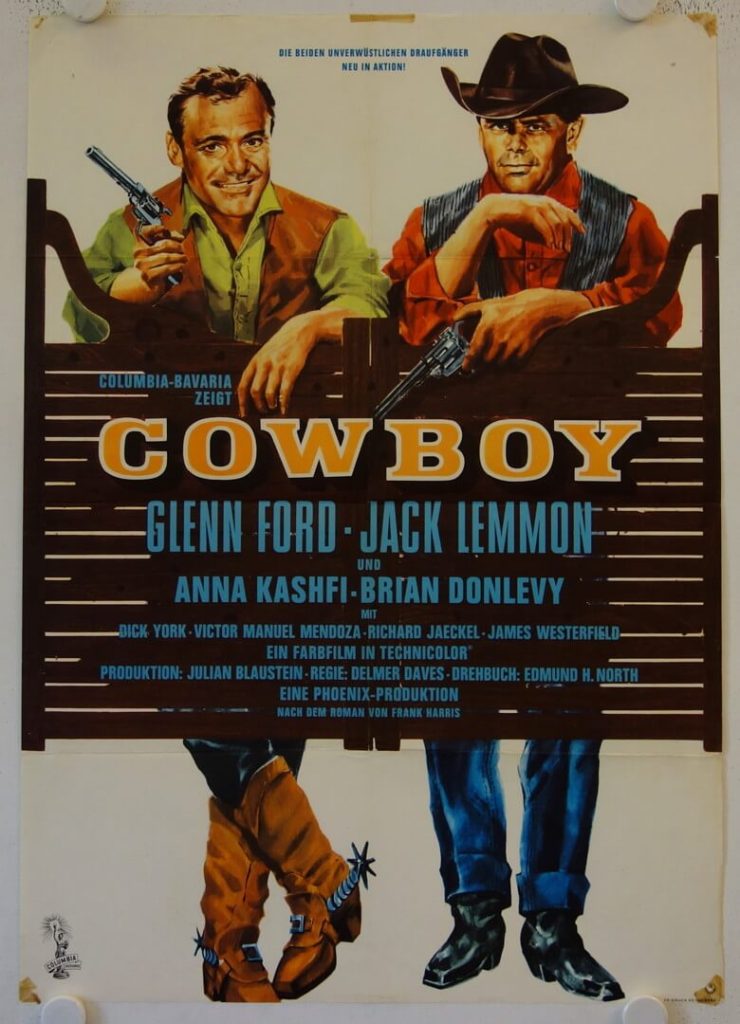

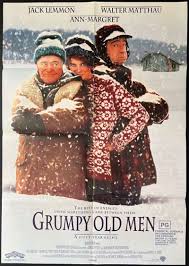

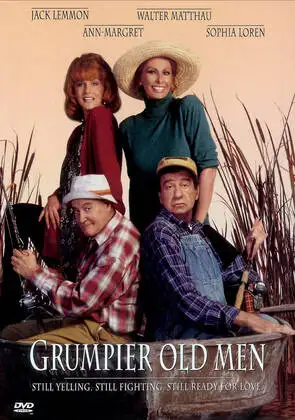

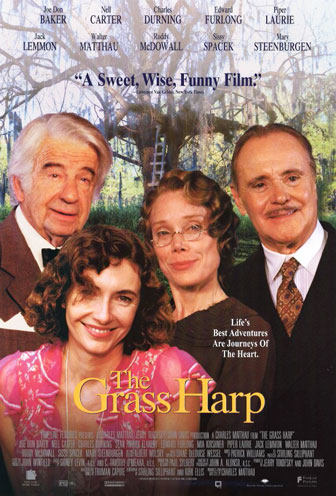

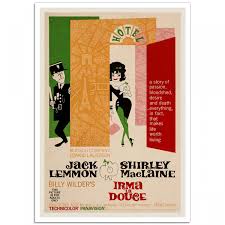

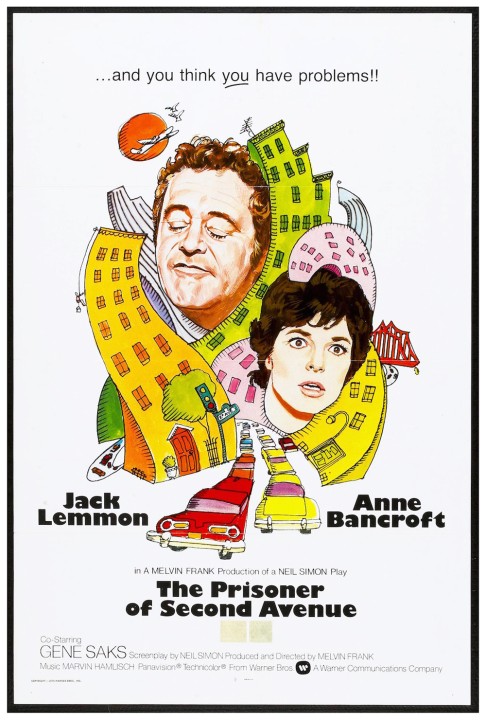

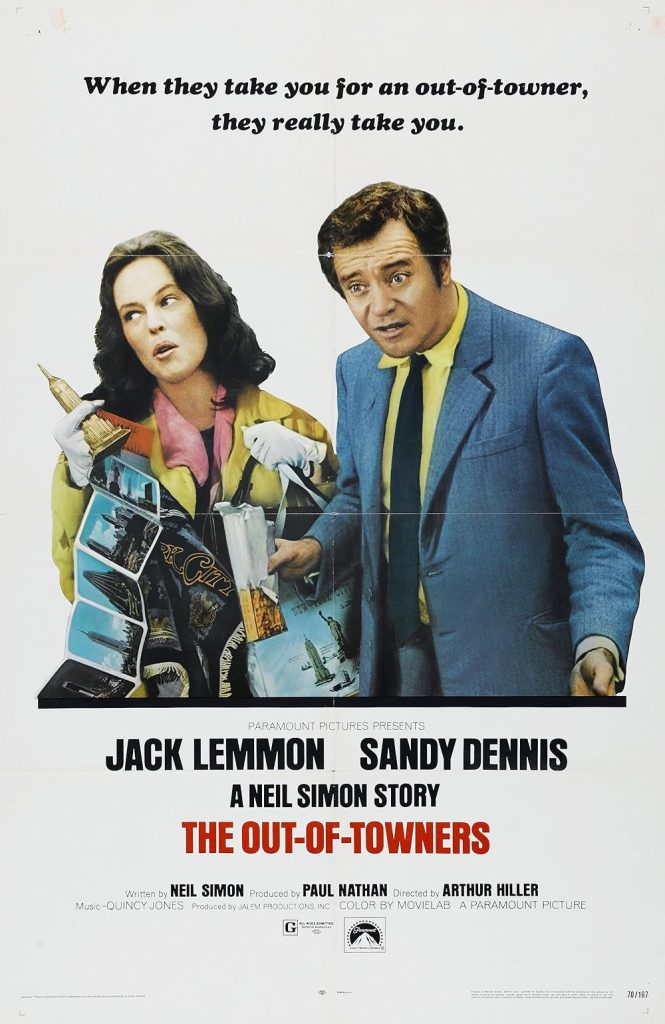

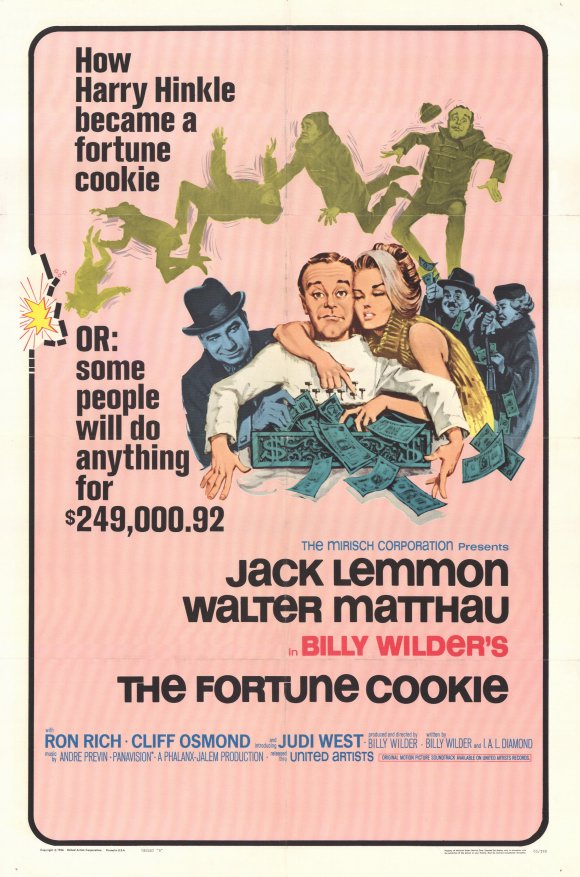

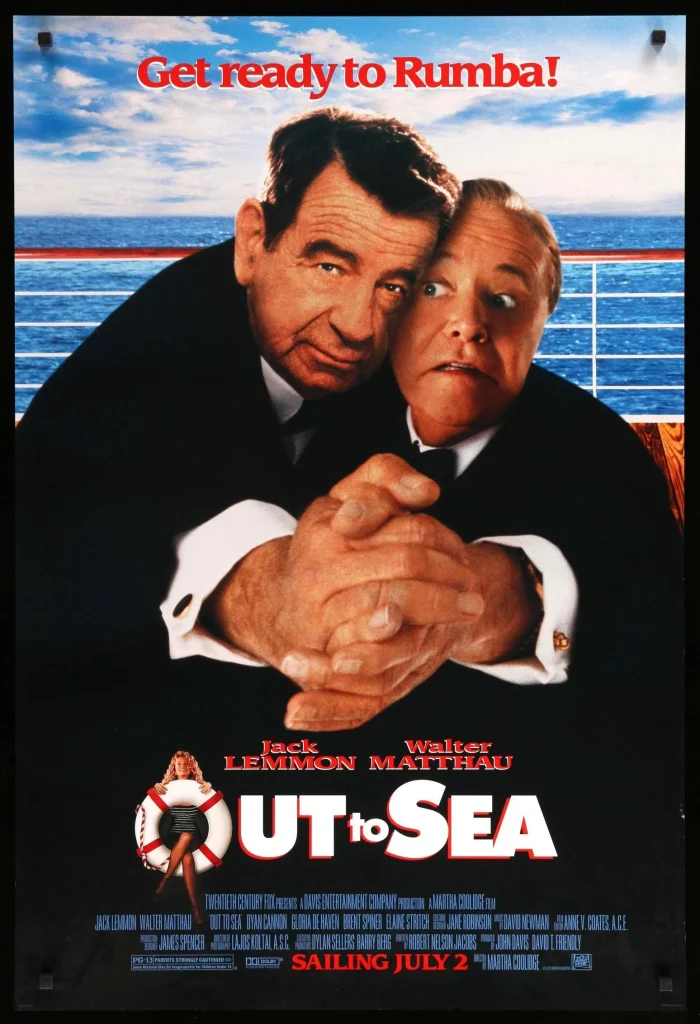

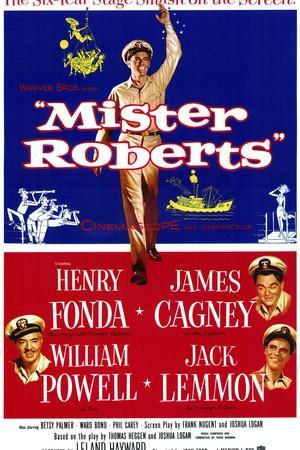

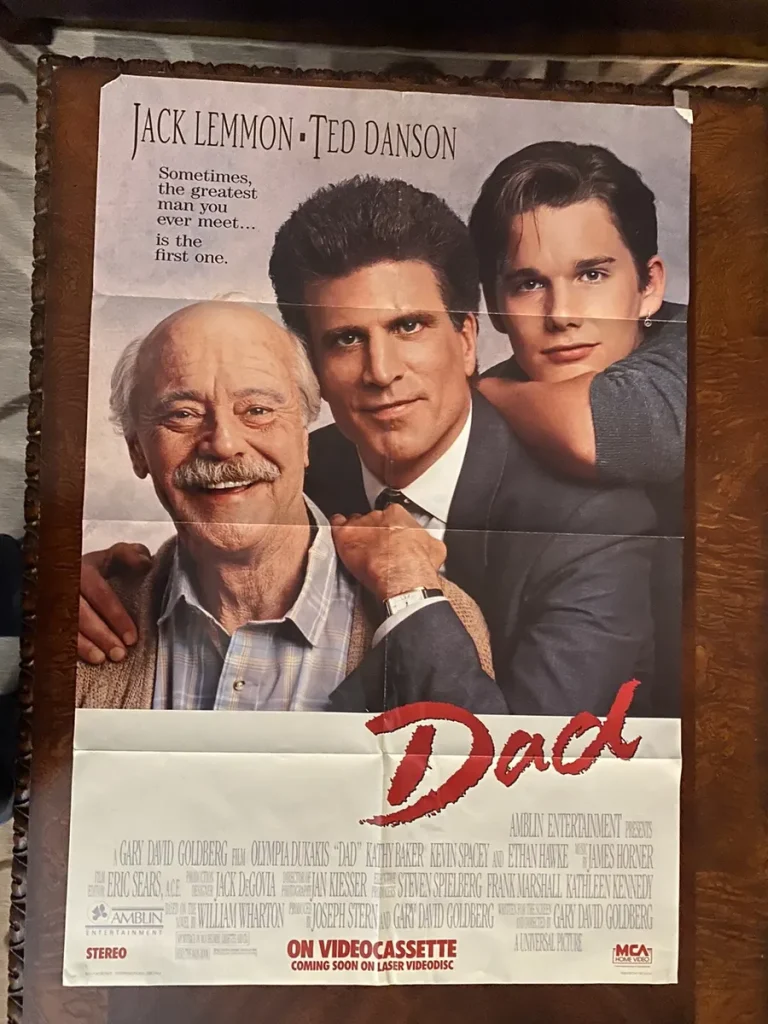

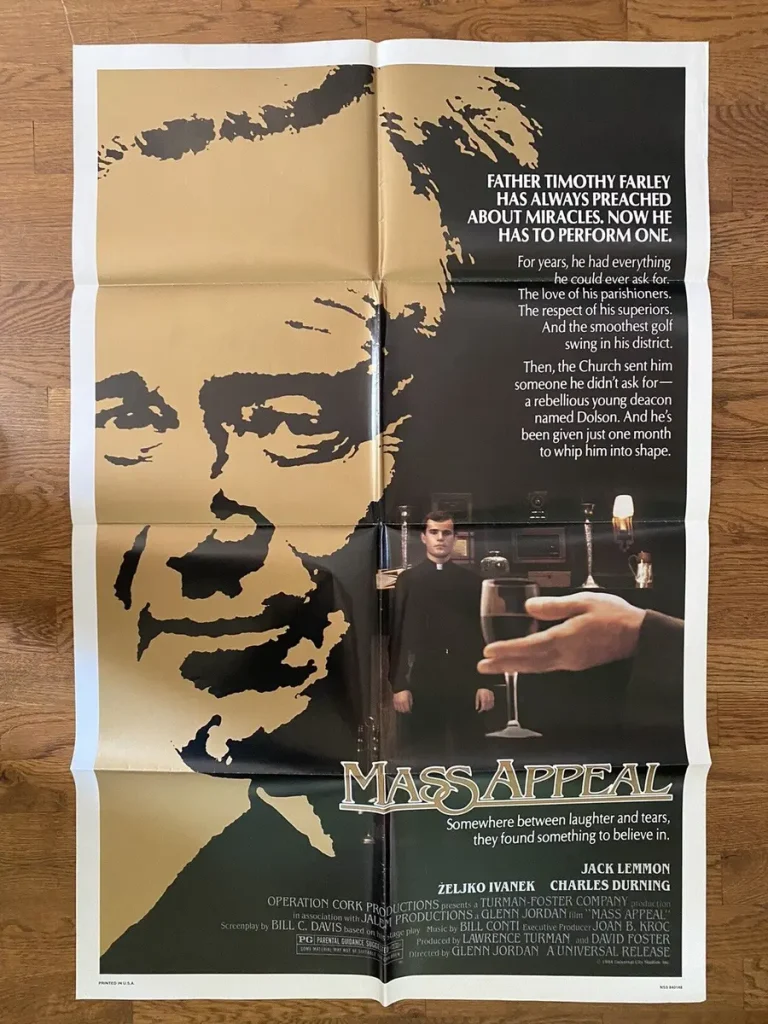

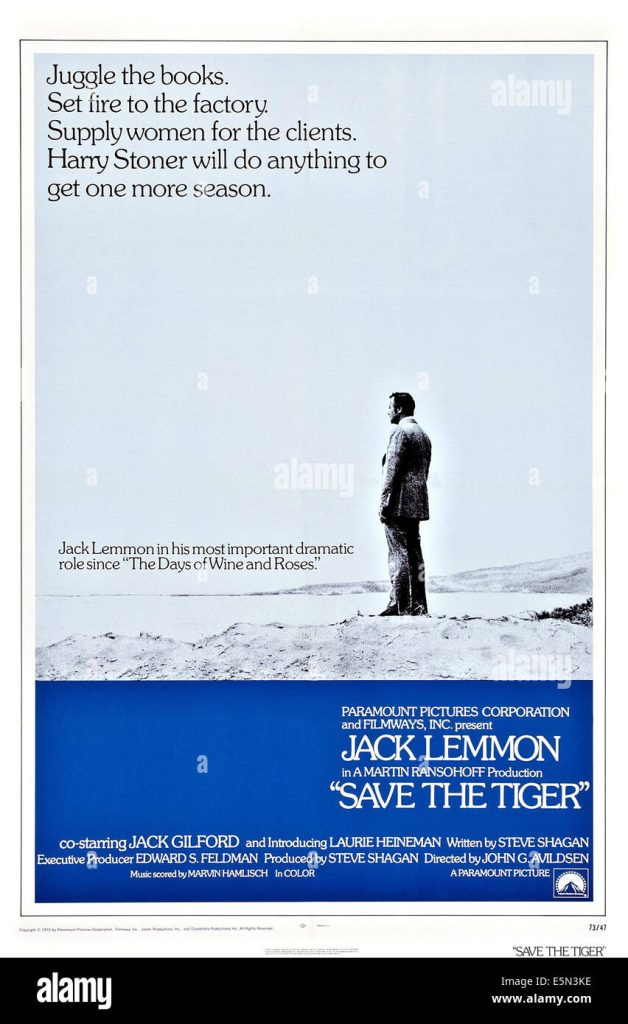

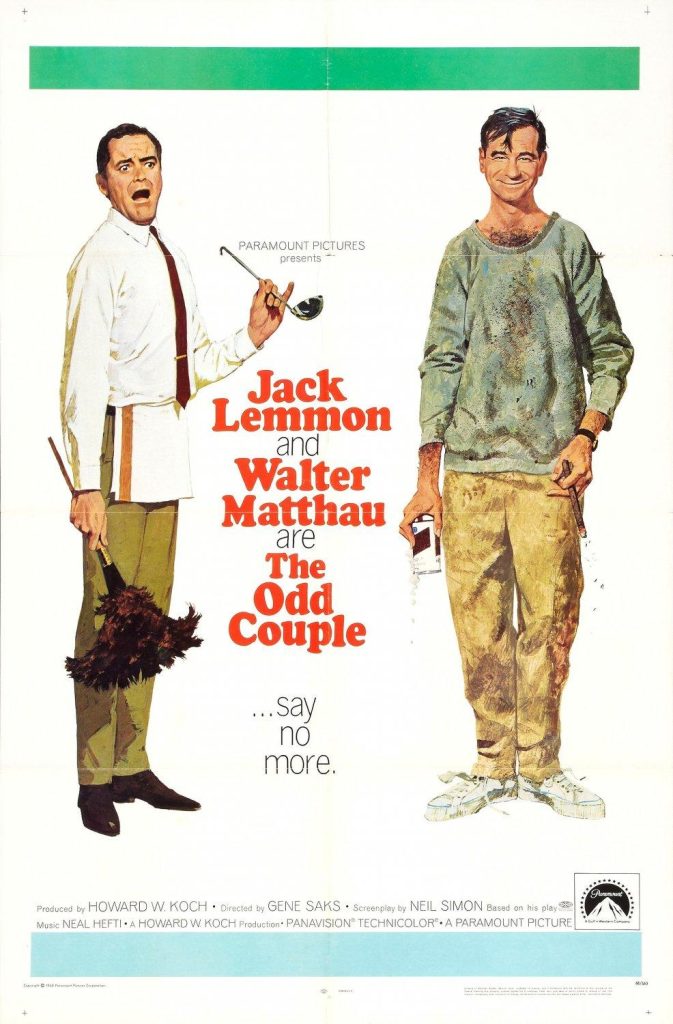

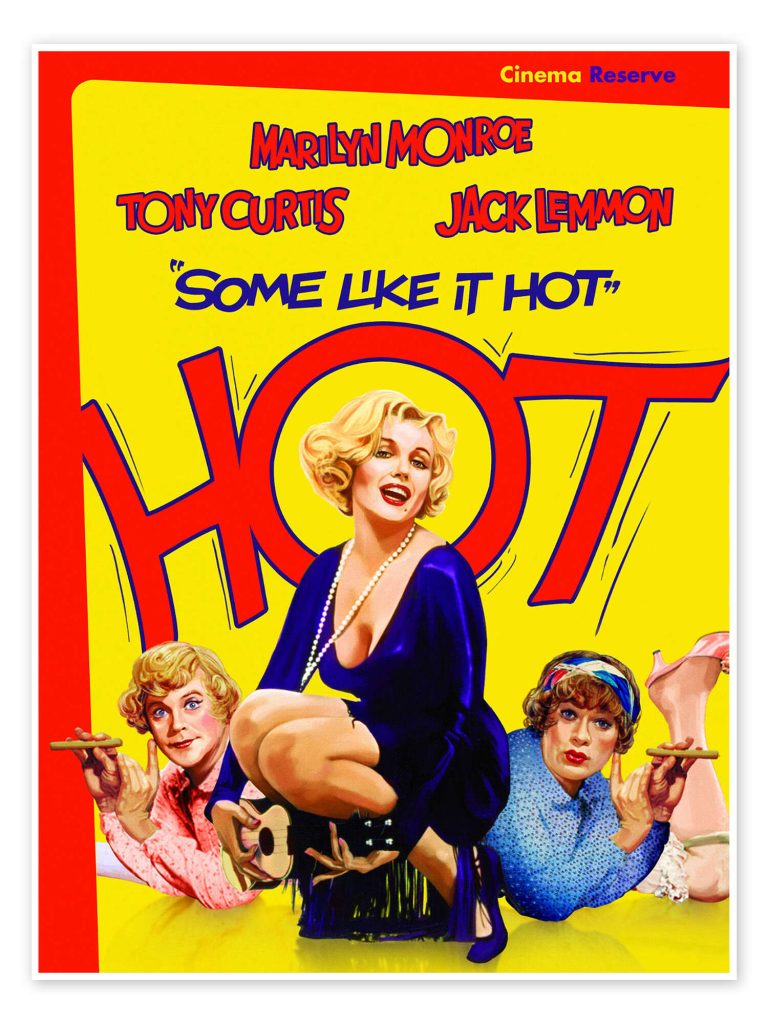

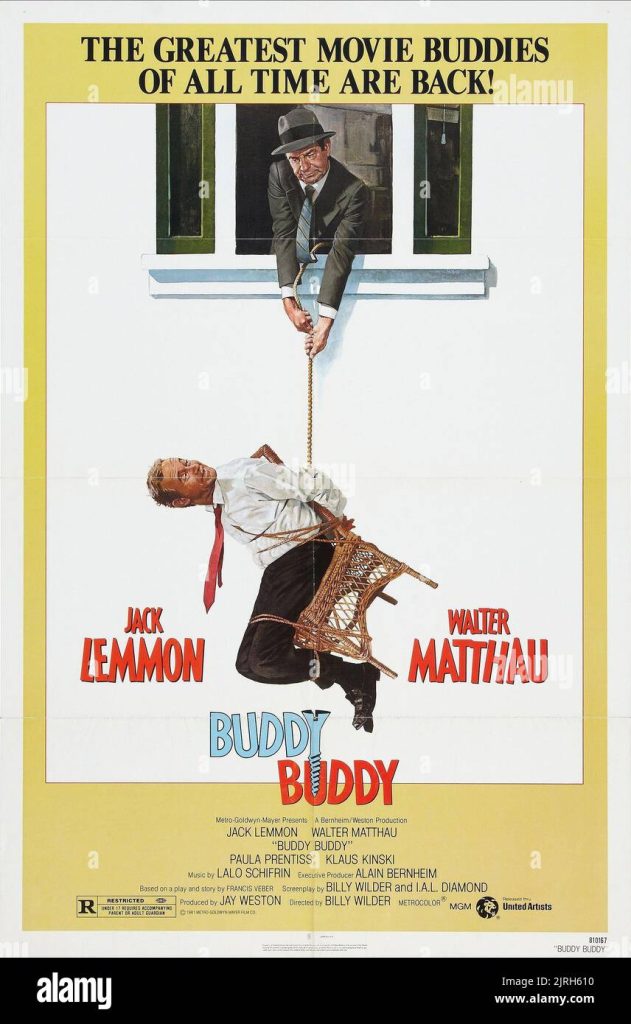

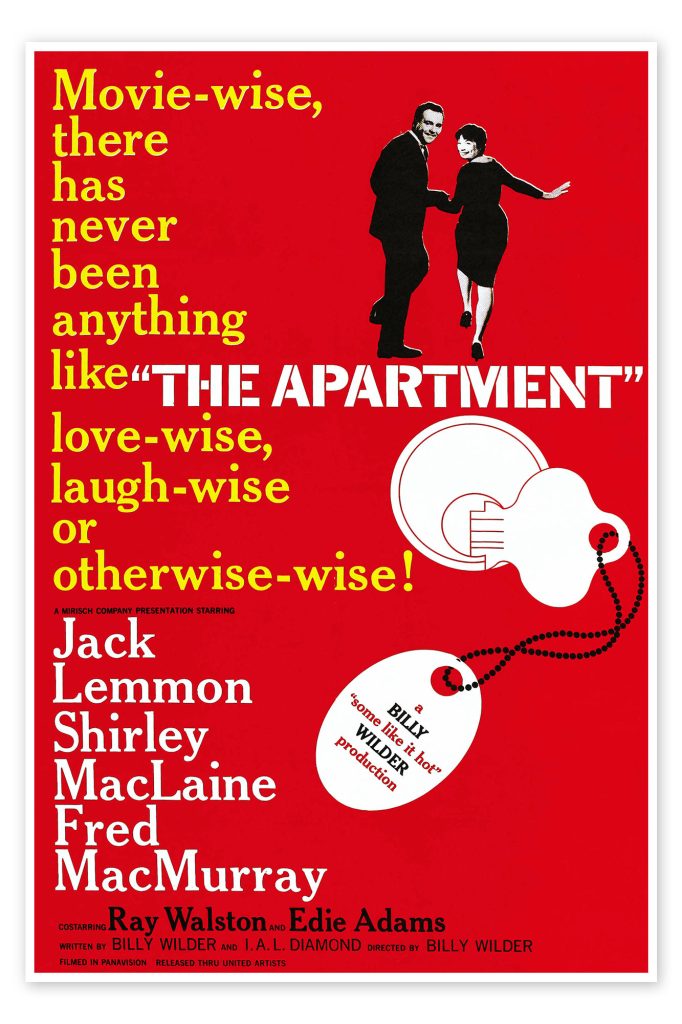

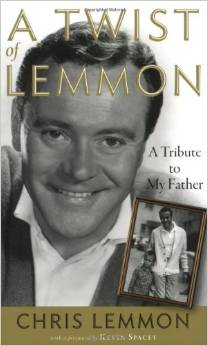

Jack Lemmon was born in 1925 in Newton, Massachusetts. He has had one of the popular and prolific career that any Hollywood actor could wish for. He began by playing callow young men opposite such powerhouse ladies as Betty Grable and Judy Holliday. By the late 1950’s he had developed into a sterling comedic actor starring in such movies as “Some Like It Hot” with Marilyn Monroe and Tony Curtis in 1959 and “The Apartment” with Shirley MacLaine in 1960. He won two Oscars, for “Mr Roberts” in 1955 and “Save the Tiger” in 1973. He starred opposite some of the most iconic leading ladies of the 60’s and 70’s including Doris Day, Romy Schneider, Anne Bancroft and Jane Fonda. He died in 2001. His widow is the actress Felicia Farr.

Duncan Campbell’s obituary of Jack Lemmon in “The Guardian”:

The world of entertainment and millions of fans were yesterday mourning and paying tribute to Jack Lemmon, who died in a Los Angeles hospital following complications related to cancer. The star of Some Like It Hot, The Odd Couple and Missing, and the winner of two Oscars, was 76.

His wife, Felicia, his two children and his step-daughter were at his bedside when he died. He had been in and out of the University of Southern California/ Norris Cancer Clinic in Boyle Heights during the last few months as his condition deteriorated. He underwent surgery a month ago to remove an inflamed gall bladder. Although he died on Wednesday night, news of his death was not made public until early yesterday.

“He is one of the greatest actors in the history of the business,” said his publicist and longtime spokesman, Warren Cowen. “To say one word about him would be ‘beautiful.’ It’s an opinion that is shared by everybody who knew him.”

His death comes almost exactly a year after his old friend and partner in The Odd Couple, Walter Mathau, died of a heart attack. “Happiness is working with Jack Lemmon,” is how the director Billy Wilder once described him.

“What marks all the best work Lemmon has done are some trace elements of the man himself, some perceived truth that as clown or tragic figure, the persona within the character is likable, decent, intelligent, vulnerable, worth knowing; disorganised possibly, flawed almost certainly, but forever worth knowing,” was the assessment of the Los Angeles Times film writer, Charles Champlin.

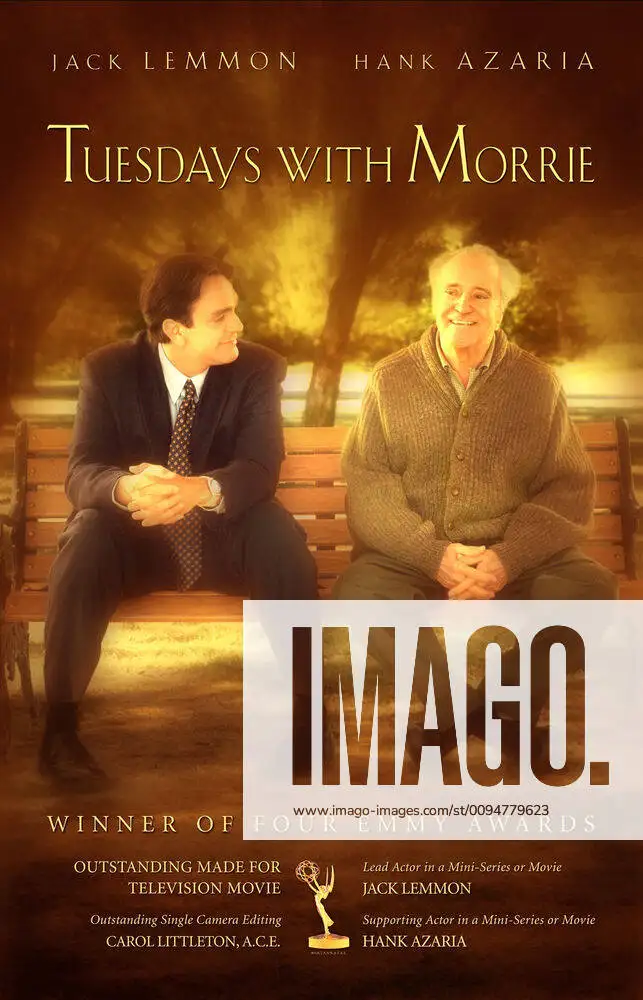

In 1999, he performed in the television drama Tuesdays With Morrie, for which he won an Emmy and in which he had an opportunity through his role to reflect on death. He was already ill with cancer.

Enormous range

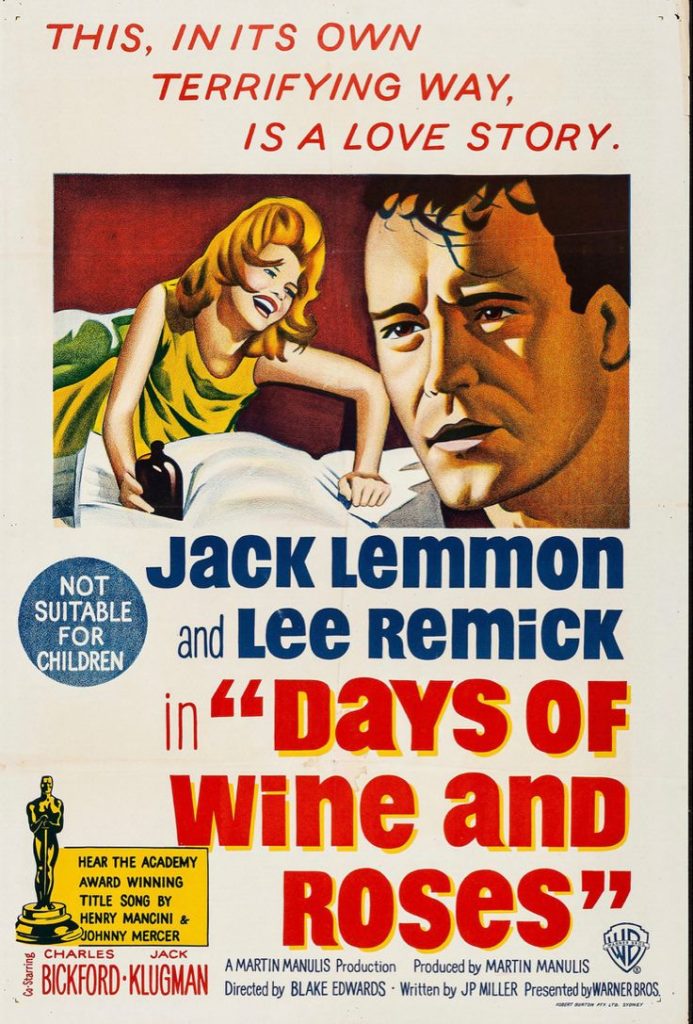

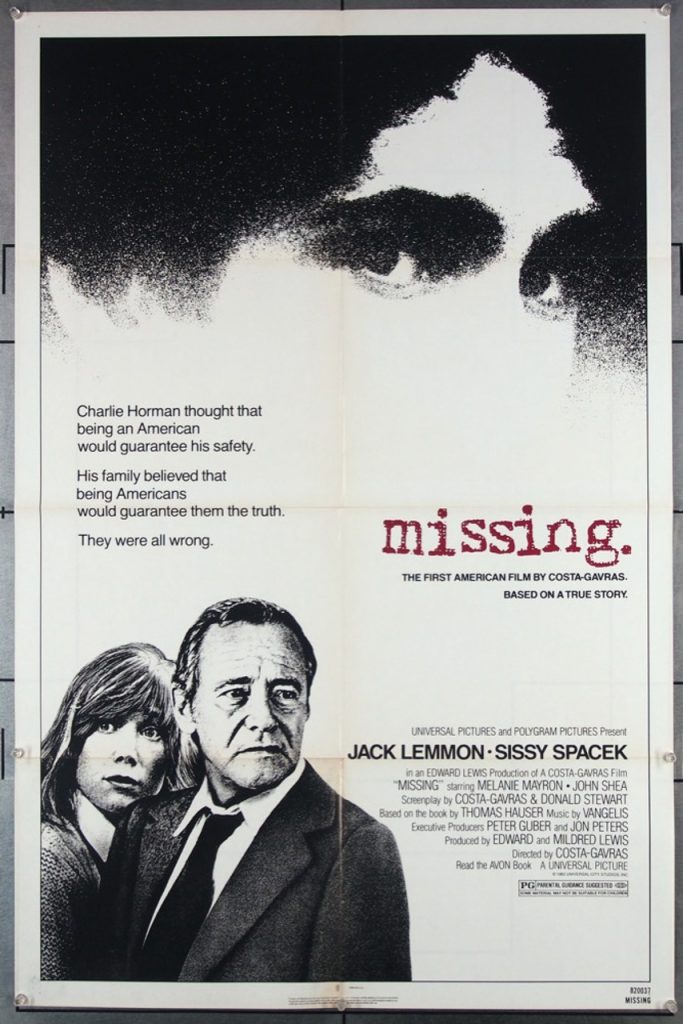

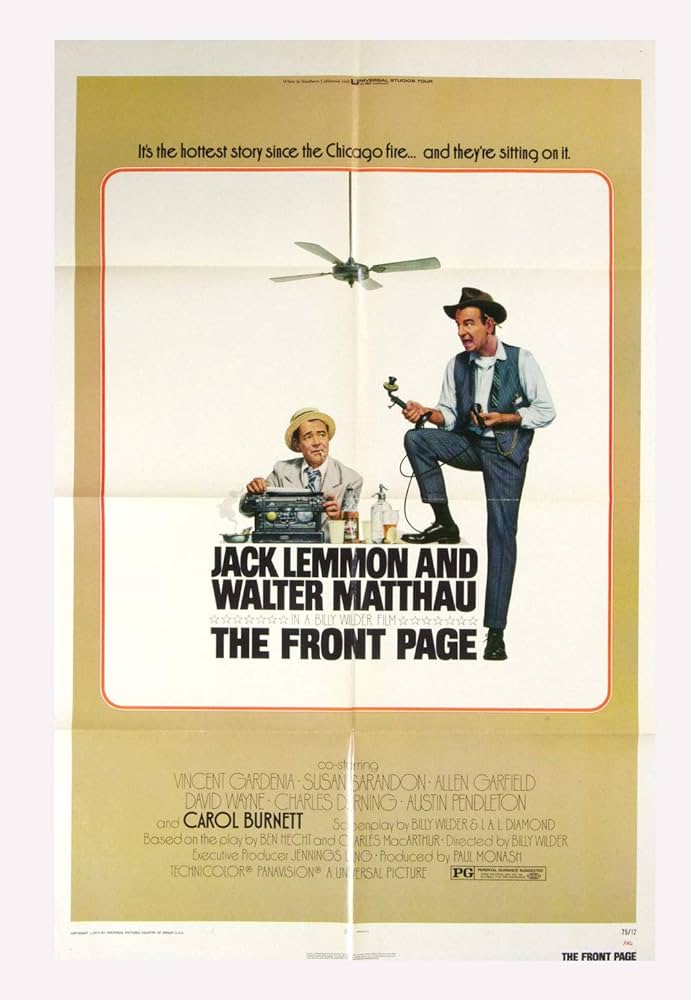

While he may be best remembered for his roles as the musician who had to dress in drag to escape the mob in Some Like It Hot, and as Felix Unger in The Odd Couple, Lemmon’s range was enormous. Whether playing the distraught father of a son missing during the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile in the film Missing, or an alcoholic in The Days of Wine and Roses, or a speedy newspaper man in The Front Page, he managed to bring something different to the role.

Although regarded as one of the great comic actors in the history of film, five of his seven Oscar nominations were for roles in dramas rather than comedies.

Born in 1925 in a lift in a hospital in Newton, Massachusetts, legend had it that he had a case of jaundice which prompted a nurse to remark: “My, look at the little yellow Lemmon.” John Uhler Lemmon III was the son of the owner of a bakery who suffered from childhood illnesses and required 13 operations before he was 13.

After studying at Harvard and serving in the US navy as an ensign in the second world war, Lemmon embarked on an acting career first in the theatre in New York, then on radio, television and film, that spanned half a century. He even managed to resist pressure from the legendary studio boss, Harry Cohn, who wanted him to change his name lest critics and audiences should ever be tempted to describe the movies he appeared in as “lemons”. He won an academy award for the first time in 1956 for his part as Ensign Pulver in Mister Roberts, and again in 1973 for playing a compromised businessman in trouble with the mob in Save the Tiger.

Recently, he had been reflecting on his career. Explaining his roles in Missing, The Days of Wine and Roses and The China Syndrome, in which he played a nuclear power plant operator, he said: “I like a film that has a point of view.” He said that it was not necessary for him to agree with a point of view in order to play the part, but that films that made people think always attracted him. But he was philosophical about the movie business: “We all make bad films _ you misjudge. That happens more often than the hits. But I have been able to get films that have worked, not only at the box office, but critically and with the public, often enough so that I’m still around. I can still get wonderful parts, thank God… I am passionate about acting, I love it, respect it. It gets me.” He kept acting and getting parts until near the end.

While Lemmon said he had loved his career and felt privileged to have played so many different parts, he said that his career was always much less important to him than his family. He was married from 1950 to 1956 to the actress Cynthia Stone, and their son, Chris, was born in1954. In 1962, he married the actress Felicia Farr, and their daughter, Courtney, was born in 1966. His family said yesterday that his funeral would be private.

His two most rewarding film partnerships were with the director Billy Wilder, who directed Lemmon with Marilyn Monroe and Tony Curtis in Some Like It Hot, The Apartment, Irma La Douce and The Front Page, and with Walter Mathau, with whom he starred in eight films.

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

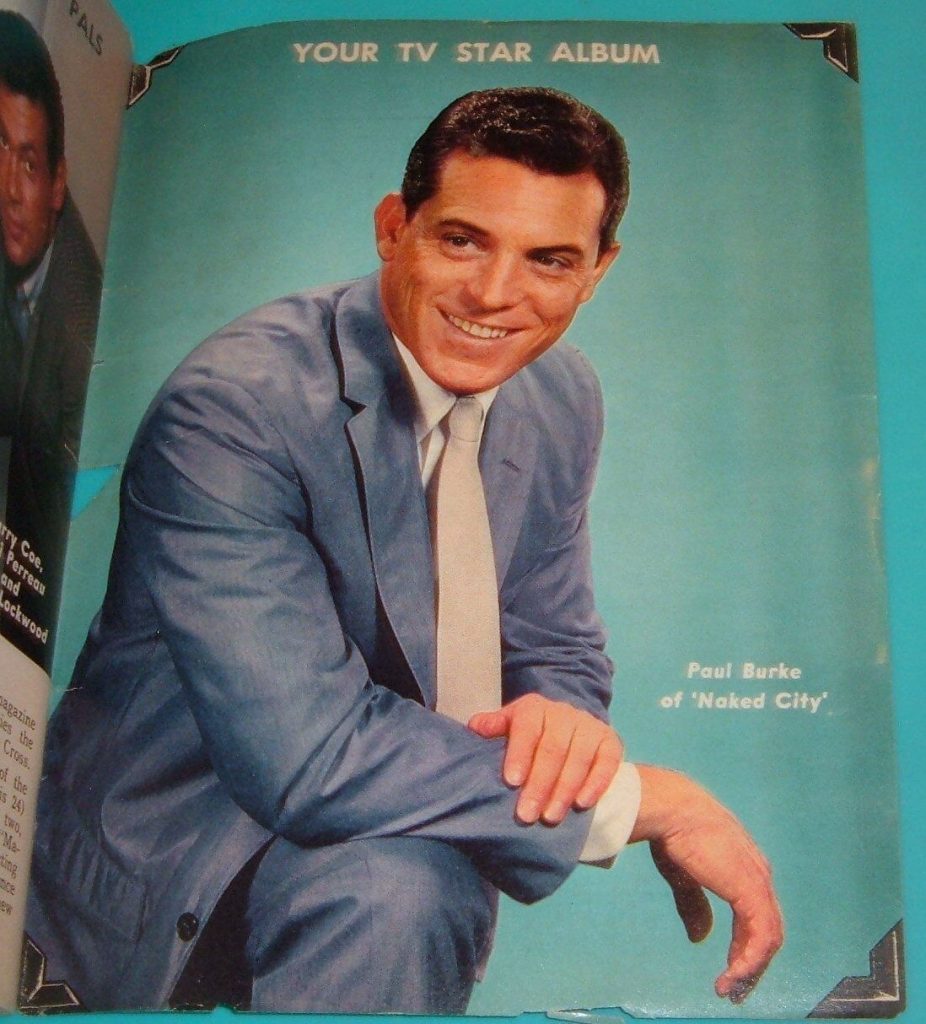

Paul Burke was born in New Orleans in 1926. He has acted in three very popular television series, “Harbourmaster” in 1957, “Naked City” fron 1960 until 1963 and “12 O’Clock High” from 1964 until 1967. His film roles include “The Valley of the Dolls'” with Barbara Parkins in 1969 and then two years later “Daddy’s Gone A Hunting” with Carol White.

Gayr Brumburgh’s entry:

Tall, dark, and handsome is how Hollywood liked their leading men back in the 1950s and 1960s, and actor Paul Burke certainly fit the bill. While his career fell short of outright stardom, he managed to stand out in a couple of acclaimed TV cop series series in the 1960s and “enjoyed” semi-cult notice by co-starring in one of the screen’s most celebrated turkeys of all time.

The New Orleans-born actor was born on July 21, 1926, the son of Martin Burke, a prizefighter who later became a well-known promoter and French Quarter nightclub owner (“Marty Burke’s”). Educated at prep schools, he was drawn to acting and moved to Hollywood in the late 1940s, studying at the Pasadena Playhouse for a couple of years. Screen director Lloyd Bacon, a friend of his father Marty, helped the fledgling actor along by giving him an unbilled part in the Betty Grable musical Call Me Mister (1951). From there, he managed to scrounge up bit/uncredited parts in such 1950s films as Fearless Fagan (1952); Francis Goes to West Point (1952), Three Sailors and a Girl (1953), South Sea Woman (1953), and Spy Chasers (1955). He moved up the ladder a bit to featured status in another Francis the talking mule picture, Francis in the Navy (1955), and inScreaming Eagles (1956), then earned a starring role in the voodoo/jungle horror flick The Disembodied (1957), opposite the “50-Foot Woman,” herself, Allison Hayes.

Better yet, Paul found steady work on the small tube with grim-faced roles in a number of crime series such as Highway Patrol (1955),

The Lineup (1954), M Squad (1957), and Dragnet (1951). He also appeared in Adventures of Superman (1952). Via an association with “Dragnet” producer/director Jack Webb, he received his own TV series, albeit short lived, in the form of Noah’s Ark (1956), portraying veterinarian “Dr. Noah McCann.” He followed that by co-starring with Barry Sullivan in another one-season series, Harbormaster (1957), a New England coast adventure yarn, and then in Five Fingers (1959), a spy drama headlining David Hedison. Another hit series came with 12 O’Clock High (1964), based on the hit film drama of the same name.

Paul’s best-known TV role, however, was as “Detective Adam Flint” in the highly praised police series Naked City (1958), replacing James Franciscus. He joined the program in the second season as the young partner of “Lt. Mike Parker” (portrayed by Horace McMahon), just as the half-hour show format was being extended to an hour. Based on the gritty, groundbreaking cop movie The Naked City (1948), the series did the film more than justice with excellent story lines, and Burke walked away with two Emmy nominations out of the three seasons he appeared.

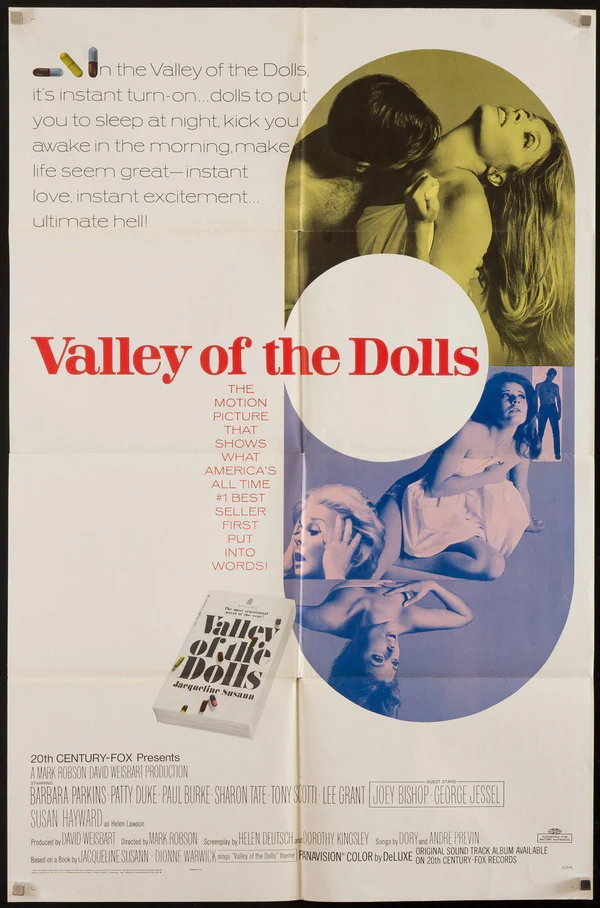

His only movie role in the early 1960s was the Joan Crawford starrer Della (1964) (aka Fatal Confinement), which was actually a failed pilot to a prospective TV series. Winning the co-lead role of fledgling writer “Lyon Burke” in the highly anticipated film adaptation of Jacqueline Susann‘s monstrous best seller, Valley of the Dolls (1967). It could have been the break to turn things around on film. It did not-far from it. The Susann book was, if anything, a guilty pleasure as readers were reeled in by the trashy Hollywood themes of drugs, fame, and sex. The movie was a laughable misfire-riddled with bad acting, bad dialogue and inept directing. It earned instant cult infamy, making many “top 10” lists for worst movie ever. It also damaged the screen careers of many of the talent involved. In reality, Paul and Barbara Parkins, who played his paramour in the movie, actually came off better and more grounded than most. Unfortunately, good or bad, they were identified with a huge turkey, and it stuck.

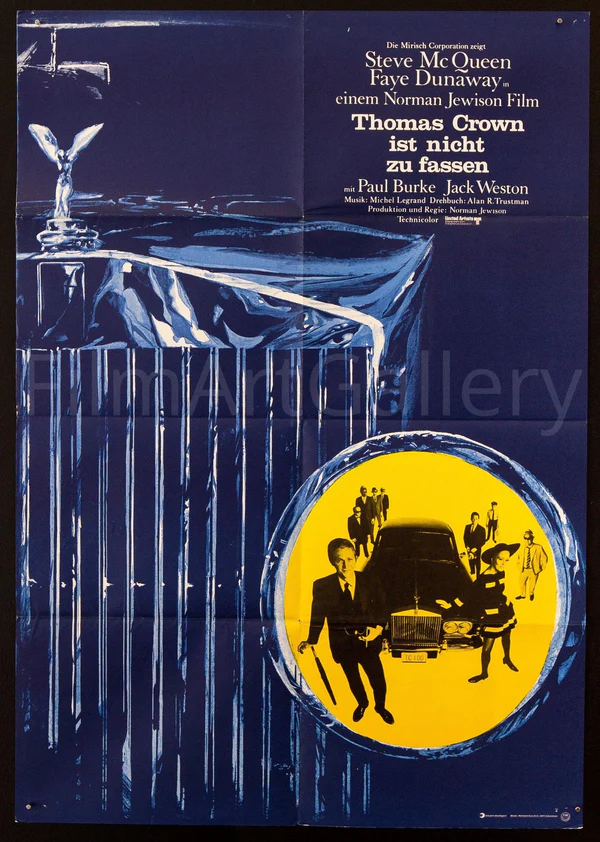

Despite Paul’s co-star cop role, opposite Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway, in the stylish thriller The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), the very next year, it was not able to right the wrong of “Dolls.” Thereafter, Paul tended to be overlooked in his later film, which included standard starring roles both here and abroad in such fare as Daddy’s Gone A-Hunting (1969), Once You Kiss a Stranger… (1969), and Maharlika (1970). TV crime, however, proved again to be a reliable paycheck for Paul with guest roles in such popular 70s series as The Rookies (1972), The New Perry Mason (1973), Police Woman (1974),Harry O (1973), Mannix (1967), Ironside (1967), and the acclaimed Police Story (1973) series. TV movies also came his way, as well, with the starring role of tycoon “C.C. Capwell” (replacing Peter Mark Richman), in the daytime soap opera Santa Barbara(1984). Paul himself was replaced after a relatively brief time.

He played assured roles in the series Hot Shots (1986) and Dynasty (1981), the latter as scheming “Congressman Neal McVane,” who frames Joan Collins‘ character for murder. Paul’s last film, (The Fool (1990), which was shot in England) and last TV guest role (in an episode of “Columbo”) both came out in 1990.

Divorced from Peggy Pryor, the mother of his three children, Paul married actress Lyn Peters in 1979. They met while she was appearing in the 12 O’Clock High (1964) episode12 O’Clock High: Siren Voices (1966). The couple eventually retired to Palm Springs, where the actor died at age 83 of leukemia and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in September of 2009.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net

His “Independent” obituary:

Paul Burke will best be remembered for the three years he spent as the star of the highly regarded television series, The Naked City, which was filmed on the streets and in the buildings of Manhattan.

Inspired by the 1948 film of the same name, it was innovative in its use of location shooting all over the metropolis, from the Staten Island Ferry to Times Square, which gave it a semi-documentary feel, and though Burke was not the most animated of actors, he was handsome and had a tight-lipped doggedness that suited his portrayal of the tough police detective who manages to maintain his integrity and idealism despite confronting the worst aspects of Manhattan life. (The show could never be accused of glamorising New York City.)

“There are eight million stories in the naked city… this has been one of them,” intoned the narrator-producer Mark Hellinger at the end of the movie, and the same words were uttered at the climax of every episode of the television series (shown in the UK by ITV). Although Burke starred in other television shows and had a recurring role in Dynasty, his film career was chequered, despite his playing the leading male role in the colossal hit Valley of the Dolls (1967) and giving arguably his finest performance as the police detective determined to outwit bank robber Steve McQueen in The Thomas Crown Affair (1968).

Born in New Orleans in 1926, Burke was the son of the prize fighter Martin Burke (who once fought the world heavyweight champion Gene Tunney). After retiring from the ring, he opened a restaurant and night club, Marty Burke’s, in the city’s French Quarter. Paul used to help out in the club, and later stated that seeing some of the customers affected his outlook: “I stayed up late watching the barflies, the brawlers. I watched the effect of wasted lives. It gave me a strong feeling of urgency about my own life.”

In his early 20s he moved to Hollywood and studied acting at the Pasadena Playhouse. The director Lloyd Bacon, one of his father’s friends, got him his first screen roles, uncredited parts in the musicals Golden Girl and Call Me Mister (both 1951), the latter a Betty Grable vehicle in which he played a soldier. He was a soldier also in Sam Fuller’s Fixed Bayonets (1951), and he had small roles in two films featuring Francis, the talking mule – Francis Goes to West Point (1952) and Francis in the Navy (1955), plus South Sea Woman (1953), with Burt Lancaster and Virginia Mayo.

He graduated to guest-star roles in such television series as Highway Patrol, Dragnet and M Squad, and in 1964 he co-starred with Joan Crawford and Diane Baker in a TV movie, Della, a fanciful tale in which he was Crawford’s lawyer who falls in love with her daughter, unaware that she has a skin disease that will be fatal if she is exposed to sunlight. His first recurring role on television was that of a veterinarian in a short-lived television series, Noah’s Ark (1956-57), followed by Harbourmaster (1957-58) with Barry Sullivan, and an unsuccessful spy series, Five Fingers (1959), which was loosely based on the Joseph L. Mankiewiez film of 1952.

The Naked City began its television life as a weekly 30-minute show in 1958, with John McIntire and James Franciscus playing the roles originated in the movie by Barry Fitzgerald and Don Taylor. Despite good reviews, its ratings were poor. McIntire’s character was killed off halfway through the season, and the show itself was cancelled at the end of the year, but the production staff and one of the sponsors successfully lobbied the network, ABC, to revive it as an hour-long series, which first aired in 1960, starring Burke as Detective Adam Flint with Nancy Malone playing his loyal, if sometimes stressed, girlfriend. Harry Bellaver was Burke’s older partner and Horace McMahon his crusty superior.

Burke received two Emmy nominations for his performance, and was admired for doing several of his own stunts. “Once I had to jump from one roof to another,” he told the columnist Hedda Hopper, “when the stuntman refused because it was too windy to take a chance.” To prepare for the role, he accompanied police detectives on raids, commenting, “I know areas of the city that are truly jungles. I wouldn’t be a detective there for $1,000 a day.” Before an episode in which his character was to witness an execution, he spent a night in Sing Sing prison. “The area of the condemned has barred windows that look down over the Hudson,” he said. “You can see trains going by, as if to emphasise the life outside that is to be taken away. I was not against capital punishment before we made that show – but now, I don’t know.”

When The Naked City ended its run in 1963, it was described by the Los Angeles Times as, “television’s finest weekly hour. It took the police show and gave it a dignity and compassion that at times approached high tragedy.” Stirling Silliphant, later to win an Oscar for scripting In The Heat of the Night, was primary writer on the series, Billy May provided the jazzy theme music, and directors included John Brahm, Buzz Kulick, Arthur Hiller and Tay Garnett.

The New York location offered a pool of theatrical acting talent, some of them newcomers on the threshold of distinguished careers – they included Robert Redford, Tuesday Weld, Walter Matthau, Dustin Hoffman, Robert Duvall, Dennis Hopper, Peter Falk, Martin Sheen, Rip Torn, Jon Voight and Christopher Walken. The show’s quality, and its tradition of building shows more around the guest stars than its regular cast, also prompted seasoned performers to seek out roles, among them Eli Wallach, Viveca Lindfors, Betty Field, Sylvia Sidney, Steve Cochran and Kim Hunter.

Burke had further success on television when he starred as a Second World War Air Force colonel in the series Twelve O’Clock High (1964-67). He played his first starring role in a movie when given the male lead (billed third to Barbara Parkin and Patty Duke) in Valley of the Dolls (1967), Mark Robson’s screen version of Jacqueline Susann’s best-selling novel about addiction to pills (the “dolls” of the title). Though Robson had made a splendid job of transferring a similarly exploitative novel, Peyton Place, to the screen in 1957, Valley of the Dolls was a tawdry effort which nevertheless made a fortune while doing little for Burke, whose role as a young lawyer who befriends the film’s three heroines and has an affair with Parkin, was colourless.

Norman Jewison’s The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), primarily a glossy vehicle for Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway, gave Burke his best screen role, as a police detective partnering insurance investigator Dunaway to trap millionaire bank robber McQueen. He was a lawyer again in Mark Robson’s Daddy’s Gone A-Hunting (1969), a thriller in which his wife (Carol White) is terrorised by an ex-boyfriend who wants her to kill her own baby because she once concealed an abortion from him. Risibly melodramatic, it effectively ended the Hollywood careers of both Burke and White.

Burke returned to television, guest-starring in such shows as The Love Boat, Starsky and Hutch, Charlie’s Angels and Murder, She Wrote. In the lavish soap opera Dynasty, he had a recurring role from 1982-88 as Congressman Neal McVane, who murders the ex-husband of Krystle Carrington, a crime for which Alexis Carrington (Joan Collins) is convicted. He also had a recurring role as Rear Admiral Hawkes in Magnum, P.I., starring Tom Selleck.

In 1990, after a role in Columbo, Burke retired to Palm Springs with his second wife, Lyn, whom he had married in 1979. “Acting is more exciting than living,” he told TV Guide during the run of The Naked City. “It’s more electric, more immediate. That’s because life is full of random elements. In acting, you select, you choose the elements. This selection allows you to get to the essence of the character, the essence of an experience.” He is survived by his wife, and three children from his first marriage.

Paul Burke, actor: born New Orleans 21 July 1926; twice married (two daughters, one son); died: Palm Springs, California 13 September 2009.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.

Marsha Hunt was born in 1917 in Chicago. She has had a very long career and her films include “Irene”, “Pride and Prejudice” in 1940, “The Human Comedy”, “Carnegie Hall”, “Diplomatic Passport” and “Blue Denim”.

IMDB entry:

Stardom somehow eluded this vastly gifted actress. Had it not perhaps been for her low-level profile compounded by her McCarthy-era blacklisting in the early 1950s, there is no telling what higher tier of stardom Marsha Hunt might have reached. Perhaps her work was not flashy enough, too subdued, or perhaps her intelligence too often disguised a genuine sex appeal to stand out among the other lovelies. Two studios, Paramount in the late 30s and MGM in the early 40s, failed to complete her star. Nevertheless, her talent and versatility cannot be denied. This glamorous, slimly handsome leading lady offered herself to well over 50 pictures during the 1930s and 1940s alone.

Christened Marcia Virginia Hunt, the Chicago-born actress was the younger of two girls born to an attorney and voice teacher/accompanist. The family relocated to New York when she was quite young and she attended such schools as P.S. No. 9 and Horace Mann School for Girls. She developed an exciting interest in acting at an early age (3), performing around and about in school plays and at church functions. Following her high school graduation, the young beauty found work as a John Powers model and also as a singer on radio, a gift obviously inherited from her mother. Marcia (she later changed the spelling of her first name to Marsha) studied drama at the Theodora Irvine Drama School (one of her fellow students was Cornel Wilde).

Encouraged to try Hollywood by various New York people in the business, the young photogenic hopeful moved there in 1934. She was still only 17 but was accompanied by her older sister. It didn’t take long for the studios to take interest in her and she was signed up by Paramount not long after. Marsha’s very first first movie was in a featured role opposite Robert Cummings and Johnny Downs in the old-fashioned The Virginia Judge (1935). Displaying an innate, fresh-faced sensitivity, she moved directly into her second film playing the title role in Gentle Julia (1936), this time with Tom Brown as her romantic interest.

Marsha continued to show promise but these well-acted roles were, more often than not, overlooked in mild “B” level offerings. Appearing in co-starring roles in everything from westerns (Desert Gold (1936) and Thunder Trail (1937)) to folksy or flyweight comedyEasy to Take (1936) and Murder Goes to College (1937), she could not find decent enough scripts at Paramount. Though she was once deemed one of Paramount’s promising starlets, one her last films for the studio was another prairie flower role —Born to the West (1937) — with cowboys John Wayne and Johnny Mack Brown vying for her attention. At about this time (1938) she married Jerry Hopper, a Paramount film editor who turned to directing in the 1950s. This marriage lasted but a few years.

Freelancing for a time for many studios, Marsha’s more noticeable war-era work in sentimental comedy and staunch war dramas came from MGM, and she finally signed with them in 1939. The roles offered, which included a featured part as one of the sisters inPride and Prejudice (1940) starring Greer Garson, and again as a sister to Garson inBlossoms in the Dust (1941), showed much more promise. Some of her better war-era roles came in the films Cheers for Miss Bishop (1941), Kid Glove Killer (1942) and The Affairs of Martha (1942). During this time she also sang on extended USO tours and found busy work on radio. Her best known film is arguably The Human Comedy (1943) but she wasn’t the star. Other film roles served in support to others, such as Margaret Sullavan in Cry ‘Havoc’ (1943), little Margaret O’Brien in Lost Angel (1943), and Greer Garson again in The Valley of Decision (1945). Leading roles did not come in “A” pictures.

Her MGM contract was allowed to lapse in 1945 and a second marriage in 1946 to screenwriter Robert Presnell Jr. became a higher priority. The marriage was long and happy (exactly 40 years), and lasted until his passing in June of 1986. The few pictures she made were, again, uneventful or in support of the star, although she did have a catchy, unsympathetic role in the Susan Hayward starrer Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman (1947) as a plotting secretary. In Raw Deal (1948) starring Dennis O’Keefe, she got the “raw deal” being overshadowed as a “good girl” by the “bad girl” posturings ofClaire Trevor. At this point of her career, she decided to try the stage and made her Broadway debut in “Joy to the World” (1948). Other plays down the road would include “The Devil’s Disciple” with Maurice Evans, “The Lady’s Not for Burning” with Vincent Priceand “The Little Hut” with Leon Ames. She even had a chance to return to her beloved singing as Anna in a production of “The King and I” and (much later) in productions of “State Fair” and “Meet Me in St. Louis”. TV also yielded some new work opportunities, including a presentation of “Twelfth Night” in which she portrayed Viola.

The seams of her film career fell apart in the early 1950s. During the late 1930s and into the 1940s she signed a number of petitions promoting liberal ideals, and was a member of the Committee for the First Amendment. A strong supporter for freedom of speech, these associations led to her name appearing in the pamphlet Red Channels. Although she and her writer husband, Robert Presnell Jr., were never called before the House Un-American Activities Commission, their names were nevertheless smeared in Hollywood. While she still found film work on occasion, it was rare. Working busily from 1935 until 1949, in over 50 films, she made only three films in the next eight years. Her screenwriter husband would be credited for only one film from 1948 to 1955.

Semi-retired by the early 1960s, stage and TV became Marsha’s focal points. She also devoted herself to civil rights causes and such humanitarian efforts as UNICEF, The March of Dimes and The Red Cross. She became actively involved with the United Nations. On the acting front she semi-retired in the 1960s, appearing only in smaller roles in five films but in numerous TV programs and mini-movies playing everything from judges to grandmas. She became the Honorary Mayor of Sherman Oaks, California in 1983, and published a book on fashion entitled “The Way We Wore” in 1993. Widowed by her second husband in 1986, the ever-vibrant Marsha, in her 90s, continues to serve on the Advisory Board of Directors for the San Fernando Valley Community Mental Health Center, a large non-profit in the San Fernando Valley that advocates for adults and children affected by homelessness and mental illness. As recently as 2006, she appeared to good advantage in the movie Chloe’s Prayer (2006).

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net

The above IMDB entry can also be accessed online here.

TCM Overview:

Marsha Hunt (born Marcia Virginia Hunt October 17, 1917 in Chicago, Illinois) is an American film, theater, and television actress. With big, bright eyes, standing five-foot-six, and always very slender, Hunt was considered very attractive in her early career. She was also a very good singer, and was a model, before Paramount Pictures signed her to a contract in 1934. During the late 1930s and into the 1940s she signed a number of petitions promoting liberal ideals. She was also a member of the Committee for the First Amendment. On October 27, 1947 she flew with a group of about 30 actors, directors, writers, and filmmakers, to Washington D.C. to protest the actions of Congress. She had worked steadily from 1935 until 1949, appearing in 52 films. After being blacklisted, she appeared in only three films in the next eight years. Some of her best outing were: Pride and Prejudice (1940), The Human Comedy (1943)and The Valley of Decision (1945). Since 1980 she has been the honorary mayor of Sherman Oaks, California. As of 2007, Marsha Hunt has served for many years and continues to serve on the Advisory Board of Directors for the San Fernando Valley Community Mental Health Center, a large non-profit in the San Fernando Valley.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

Actress who appeared with Laurence Olivier in Pride and Prejudice but found her career torpedoed by anti-communist paranoia

Monday September 12 2022, 12.01am BST, The Times

Marsha Hunt looked back fondly on her role as the plain and bookish Mary, the third of the Bennet sisters in MGM’s 1940 adaptation of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, starring Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson. “[It was] a delicious character for me to play — squinting through glasses, singing off-key, wearing sausage curls,” she recalled, adding self-deprecatingly: “I wouldn’t cause one male heart in a thousand to miss a beat.”

There was, however, a problem with her singing. She was so naturally musical that she struggled to perform sufficiently out of tune to justify Mr Bennet’s immortal line, “That will do extremely well, child. You have delighted us long enough”, and had to be coached for several weeks in the art of singing badly.

She was offered the role without an audition, having been seen by an MGM producer at previous try-outs. “I didn’t want it at first,” she said at the time of the film’s release. “But when I found I was going to be a near-sighted, squinting, priggish wallflower who sang flat and busted up romances — oh boy.”

Later she spoke of the remarkable costumes and the affect they had on the cast. “Before daylight we’d report for work. It was chilly, and we wore sweaters, sneakers . . . it didn’t matter what we came to work in,” she told Persuasions, the journal of the Jane Austen Society of North America. “But once in those costumes, everything changed — the way we stood, sat, even spoke to each other. We became different people. Not that each wasn’t enacting her own character that she was assigned in the film. But it really does transpose you, in a curious way.”

Previously Hunt, who was tall and willowy with sparkling blue eyes, had deservedly been described as “Hollywood’s youngest character actress”. Before being snapped up by MGM she had been signed by Paramount, playing her first featured role at the age of 18 opposite Robert Cummings and Johnny Downs in The Virginia Judge (1935), lisping “I love you” in a southern accent.

Despite obviously being a New Yorker, she was cast in four westerns. When she complained that she should be in easterns instead, she was told that she was best suited to westerns because her height meant she would look tall in the saddle against the skyline.

Despite making more than 50 films between 1935 and 1950, the “red scare” meant that Hunt never managed to fulfil her early promise. In October 1947 she joined the Committee for the First Amendment, a group of prominent Hollywood actors founded by the directors William Wyler and John Huston. They were flown to Washington to witness congressional hearings at which the so-called Hollywood Nineteen, a group of screenwriters, were questioned about their alleged communist affiliations.

Members of the committee were subjected to a concerted campaign of smear, misquotation and misrepresentation. “In my own case, I was quoted as saying things I would never say, at a function I never attended,” Hunt explained. When the committee returned to Hollywood, Humphrey Bogart and his wife Lauren Bacall, who had been the most prominent actors on the trip, came under pressure from Warner Brothers and announced that the trip had been “ill-advised”.

Before long Hunt was being attacked by Red Channels, an anti-communist gossip sheet. In summer 1950, after a successful Broadway performance in The Devil’s Disciple, she was on holiday in Paris when Red Channels branded her a “patriotically suspect citizen”. The publication falsely listed several affiliations under her name and listed others that were innocent. Suddenly, the offers of film roles all but dried up.

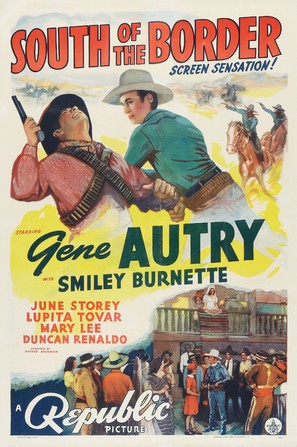

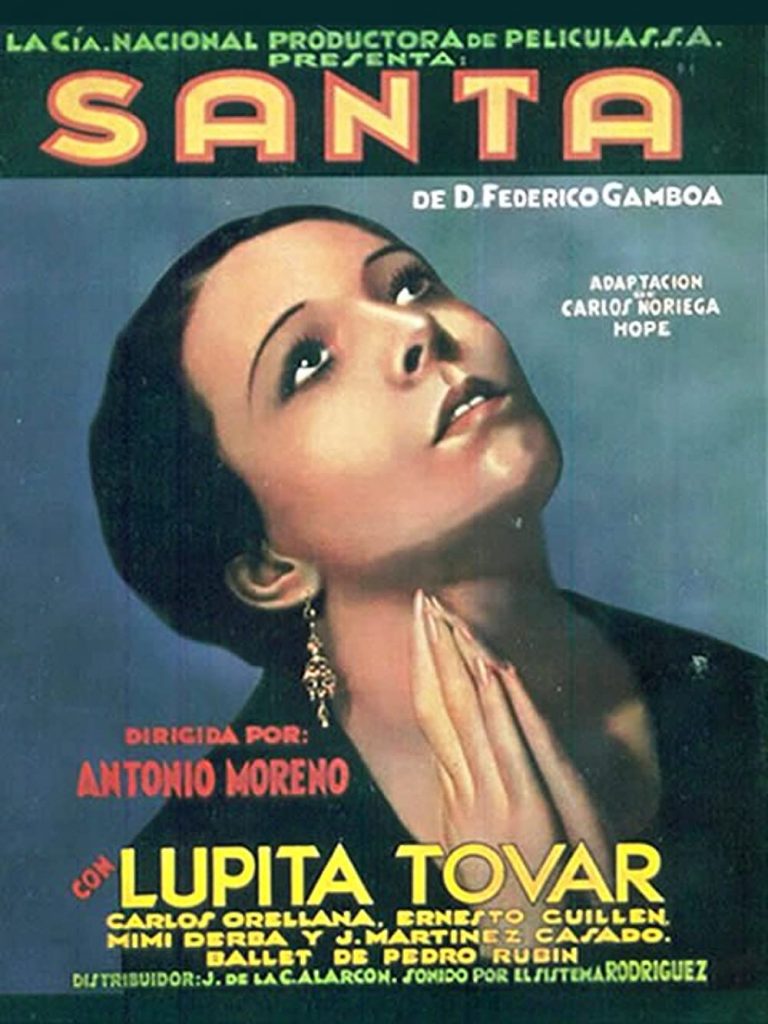

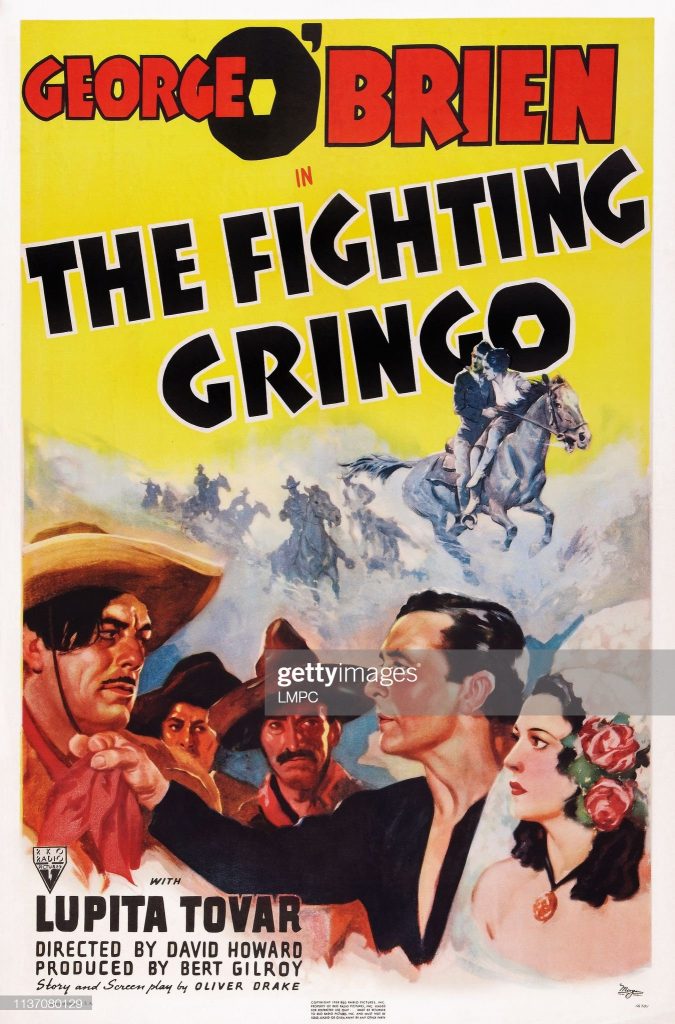

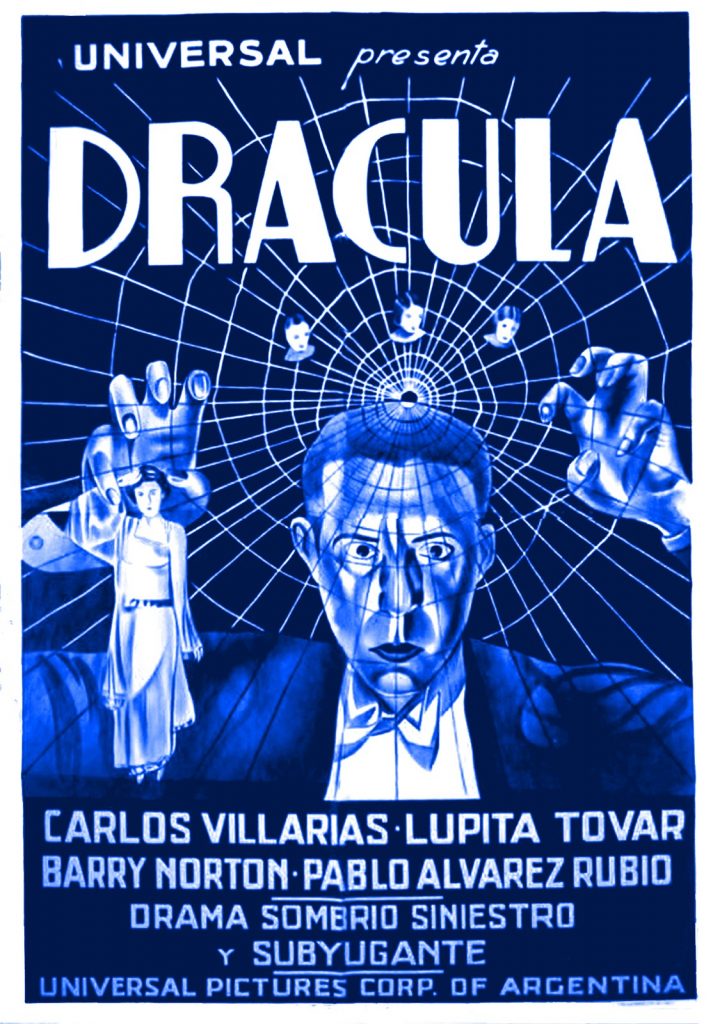

Lupita Tovar was born in Mexico in 1910. She was discovered by the documantary filmmaker Robert Flaherty. She came to Hollywood in 1929 and starred in “Dracula”, She retired early from acting when she married agent Paul Kohner in 1932. Susan Kohner the actress is their daughter. She died at the age of 106 in 2016.

Good article by Michael G Ankreich here.

IMDB entry:

Born in Oaxaca, Mexico, Lupita Tovar appeared first in silent Fox films before making the move to Universal and co-starring in the Spanish-language version of 1930’s “The Cat Creeps” (La voluntad del muerto (1930)). For the same producer, Czech-born Paul Kohner, she appeared as Eva Seward (the Spanish-language counterpart of Helen Chandler‘s Mina) in Universal’s Spanish Dracula (1931). In 1932, she married Kohner, who later became one of the top agents in Hollywood. (Their actress-daughter, Susan Kohner, was Oscar-nominated for her performance in Universal’s 1959 Imitation of Life (1959); their son, Pancho Kohner, is a producer). Tovar gave up films in the 1940s and has been widowed since 1988.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Tom Weaver <TomWeavr@aol.com>

The above IMDB entry can also be accessed online here.

“The Wrap” obituary:

Mexican screen siren Lupita Tovar has died at the age of 106.

The actress starred in the 1931 Spanish-language version of “Dracula,” which was filmed simultaneously with the popular English-speaking version with Bela Lugosi. Tovar died in her Los Angeles home on Saturday, according to a Facebook post by actress Lucy Tovar, her niece.

Tovar was the mother of Oscar-nominated “Imitation of Life” actress Susan Kohner and the grandmother to Hollywood film writers, brothers Chris Weitz and Paul Weitz. Both were nominated for an Oscar for writing 2002’s “About a Boy.” Tovar was married to high-power Hollywood producer Paul Kohner, who worked more than 50 years with icons including Greta Garbo, Lana Turner, John Huston, Lana Turner, Ingmar Bergman, Yul Brynner, David Niven, Billy Wilder and Charles Brons In “Dracula,” Tovar portrayed Eva Steward, the damsel who becomes inextricably enthralled by Dracula (Carlos Villar). Lupita starred in Mexico’s first talking film “Santa,” released in 1932. She starred opposite Buster Keaton in “The Invader,” and also notably appeared in “Blockade” with Henry Fonda. She starred in only 32 films, according to IMDb, as she chose to focus on raising her family by the mid-1940s.

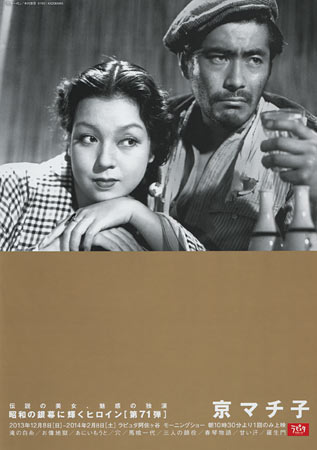

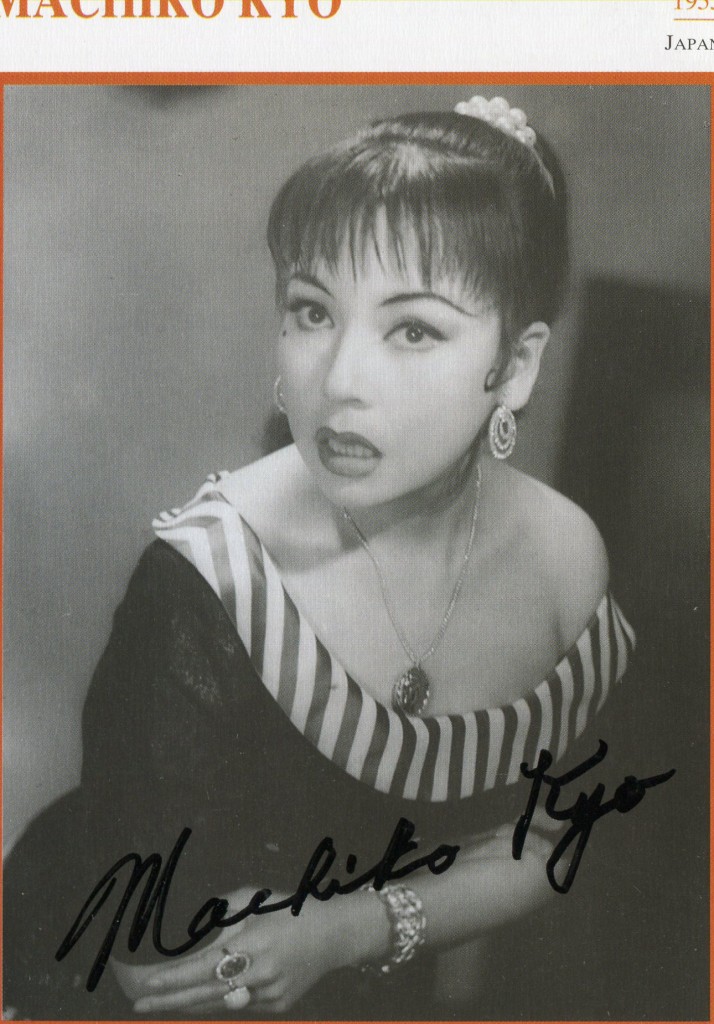

When Rashomon won the Golden Lion award for best film at the Venice film festival in 1951, and was shown widely in the west, the floodgates were opened for more Japanese films to be released worldwide.

This allowed cinephiles in the west to follow the masterful career of Rashomon’s director, Akira Kurosawa, and to discover the two forceful leads Toshiro Mifune and Machiko Kyo. Although Kyo, who has died aged 95, had appeared in a number of films previously, it was Rashōmon that enabled her to work with other greats of Japanese cinema such as Kenji Mizoguchi and Yasujiro Ozu.

In Rashomon, which is set in feudal Japan, Kyo played the wife of a samurai warrior. While the couple are travelling through the woods, they are accosted by a dangerous bandit (Mifune), who rapes the wife and kills the husband. Or does he? At the trial of the bandit, the incident is described in four conflicting, yet equally credible versions – by the bandit, the wife, the dead samurai (communicating through a medium) and a woodcutter – thus demonstrating the subjective nature of truth.

Through the four conflicting narratives, we see different aspects of the character of the wife, brilliantly played by Kyo – passionate, emotional, devious, weak and strong. Noticing the look of revulsion in her husband’s eyes, she incites the bandit to kill him; or, wielding a dagger, she kills him herself. Western audiences were not used to this kind of stylised screen acting but, as Orson Welles once said about great film performances, they were “not necessarily realistic but true”.

Early on, Kyo found herself mostly in jidai-geki (period films set in the era before the opening of Japan to western influence). For these roles, she sometimes used hikimayu, the practice of removing the natural eyebrows and painting larger and higher eyebrows on the forehead. This was most effective in Ugetsu (1953), one of Mizoguchi’s most acclaimed films.

In it, Kyo was eerily beautiful as Lady Masaka, a mysterious noblewoman who seduces a poor married potter. He later finds out that she was a ghost who had died before she could find true love.Advertisement

In one scene, Kyo showed her versatility by singing and dancing. This gave a hint of her background in the dancing troupe she had joined as a teenager. Most reports claim that she was born Motoko Yano in Osaka. However, in a Rashomonesque manner, there were a few dubious claims that she was born in Mexico, while her father was working there as an engineer, and was brought up by her mother, a geisha, after her parents split up.

While working as a dancer, Kyo was discovered by Masaichi Nagata, head of the Daiei studios in Tokyo, with whom she became romantically involved, and for whom she made Love for an Idiot (1949). This local hit, in which she played a teenage bride, gave no indication of the direction her career would take with the success of Rashomon a year later.

In Teinosuke Kinugasa’s Gate of Hell (1953), the first Japanese picture to use a western colour process (Eastmancolor), Kyo was poignant as a married lady-in-waiting who commits hara-kiri rather than submit to a 12th-century feudal warlord who desires her. The exquisite colour, costumes and decor were used almost as leitmotifs to counterpoint the emotions of the characters, especially the glowing Kyo in the title role of Mizoguchi’s The Empress Yang Kwei Fei (1955), a scullery maid who becomes empress of China.

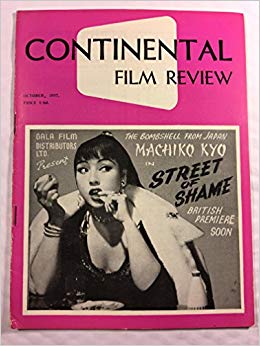

Kyo was almost unrecognisable in Street of Shame (1956), as a Americanised gum-chewing young woman who has become a sex worker in a brothel called Dreamland to spite her tyrannical father. Mizoguchi’s last completed film saw him return to an earlier contemporary subject to illustrate his major theme, the exploitation of women throughout the ages, helped to a certain degree by Kyo.

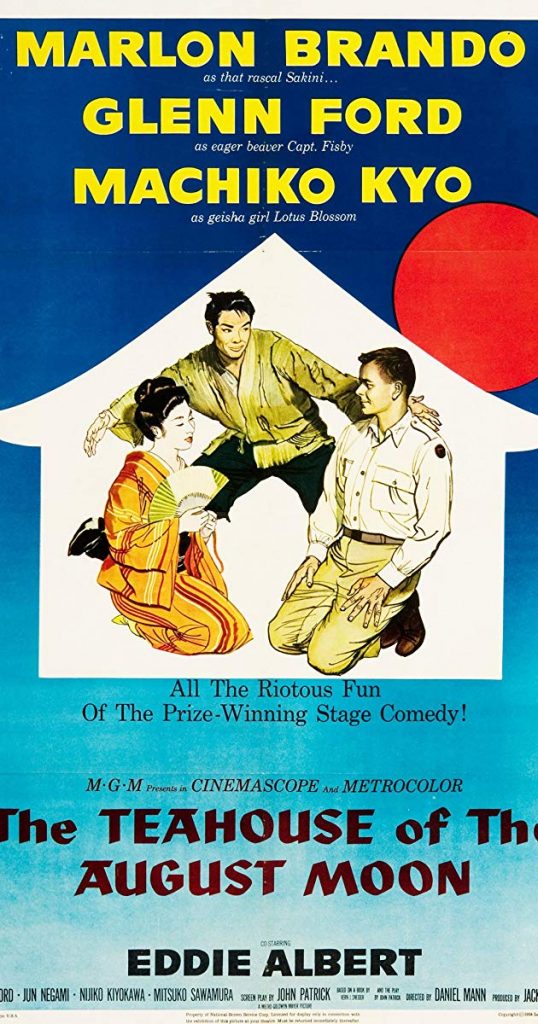

By this time, Kyo’s fame had spread worldwide, and she was invited to co-star with Marlon Brando, epically miscast as a Japanese translator, and Glenn Ford, as a bumbling officer, in the Hollywood production The Teahouse of the August Moon (1956). In this satire on American cultural imperialism in post-second world war Japan, Kyo retained her dignity as Lotus Blossom, a geisha, trying to keep GIs happy on the island of Okinawa.

Towards the end of the 1950s, considered the golden age of Japanese cinema, Kyo shifted partly and easily to gendai-geki (films in a contemporary setting), notably Ozu’s Floating Weeds and Kon Ichikawa’s Odd Obsession (both 1959). In the former, she played the scheming and jealous mistress of the leading actor of a touring kabuki theatre group, and in the latter, the young wife of an elderly man frightened by his growing impotence.

Among her films of the 60s, only The Face of Another (1966), stands out. This bizarre drama, directed by Hiroshi Teshigahara, saw Kyo deceived by her facially disfigured husband, disguised behind a handsome mask, into sleeping with him, then being accused by him of adultery.

When Daiei studios went into bankruptcy in 1971, Kyo entered semi-retirement, although she worked in television series from time to time and appeared in several commercial films into her 80s.

• Machiko Kyo (Motoko Yano), actor, born 25 March 1924; died 12 May 2019

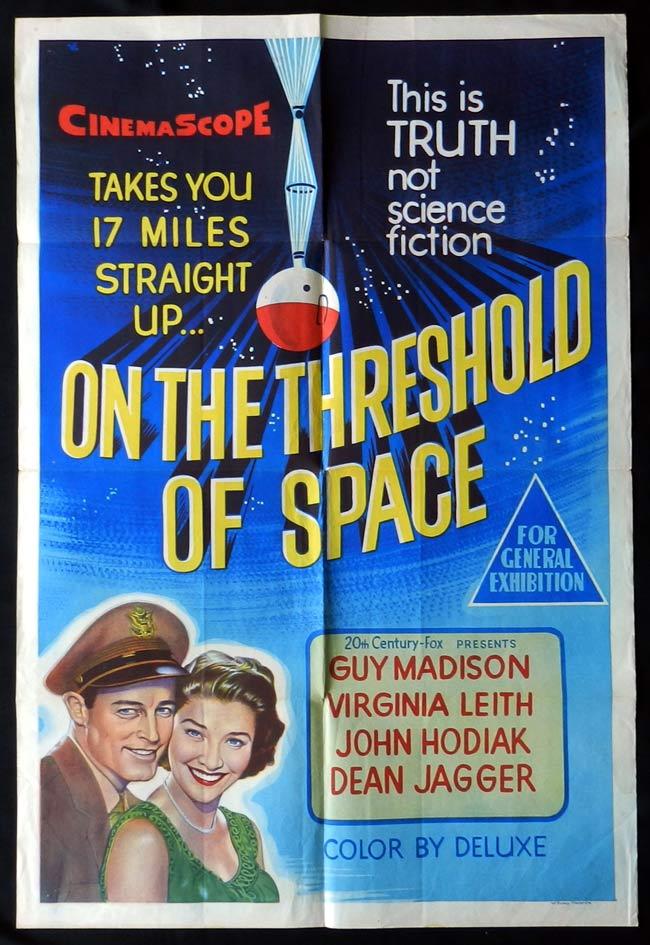

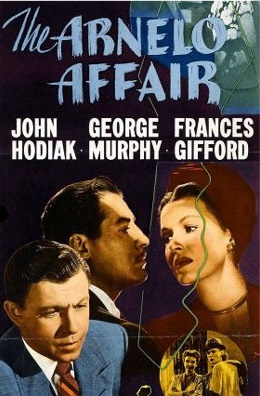

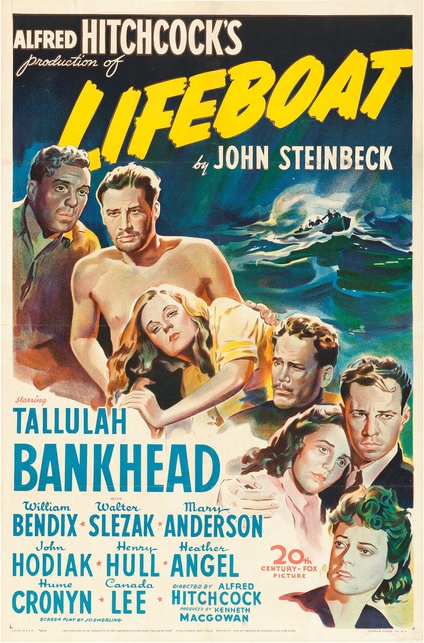

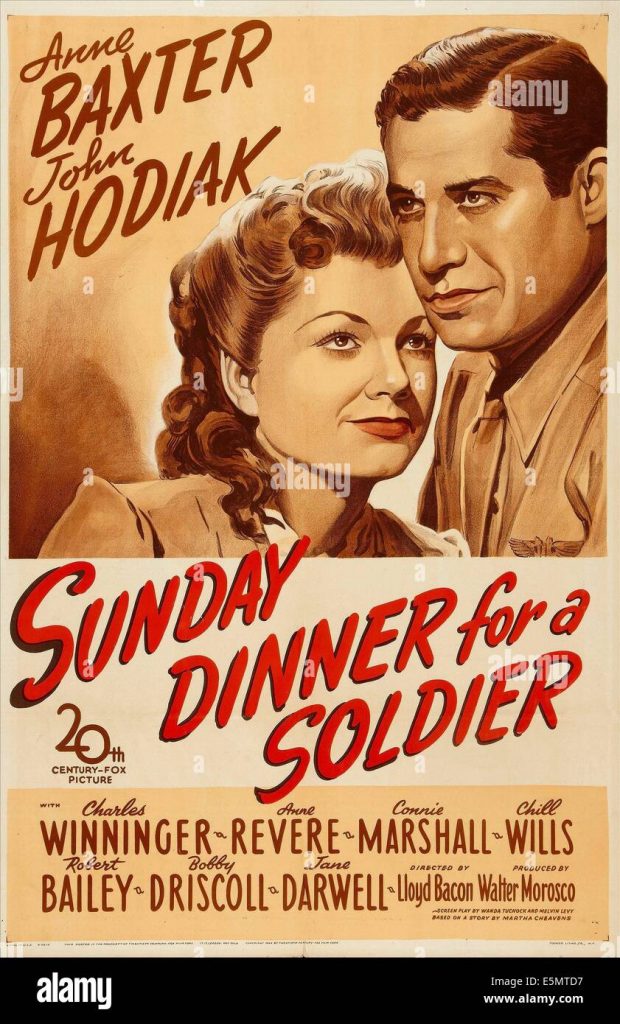

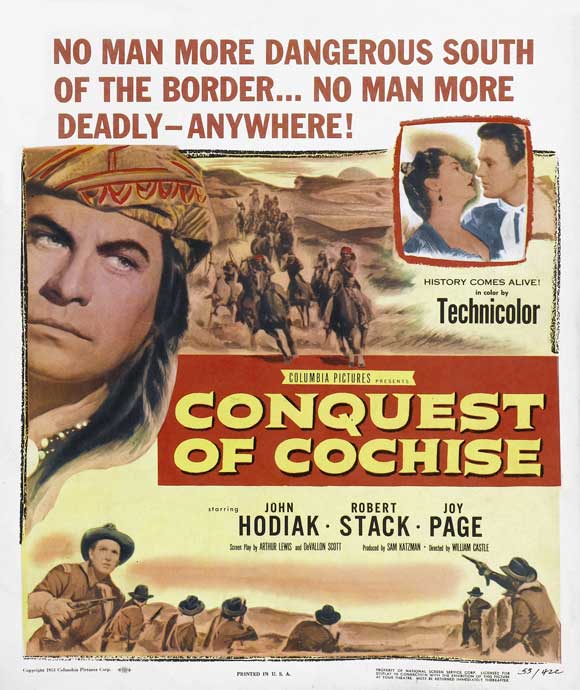

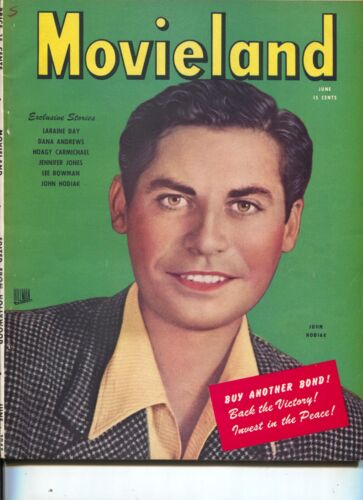

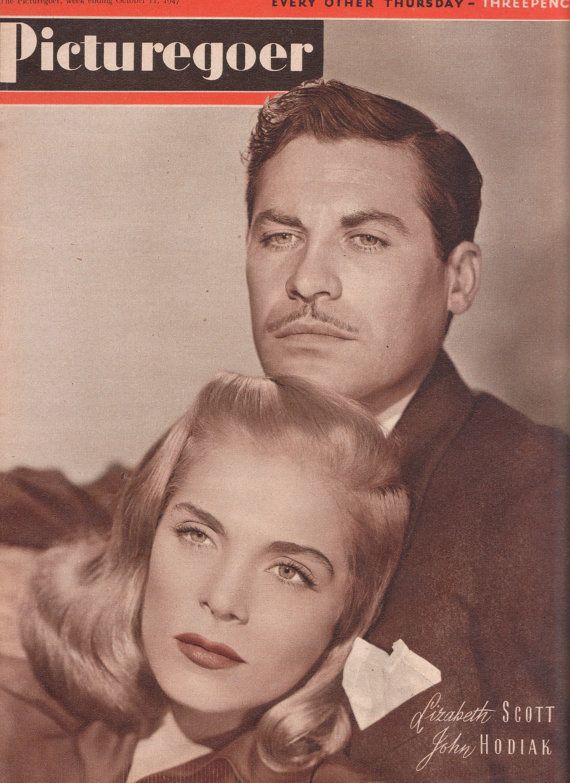

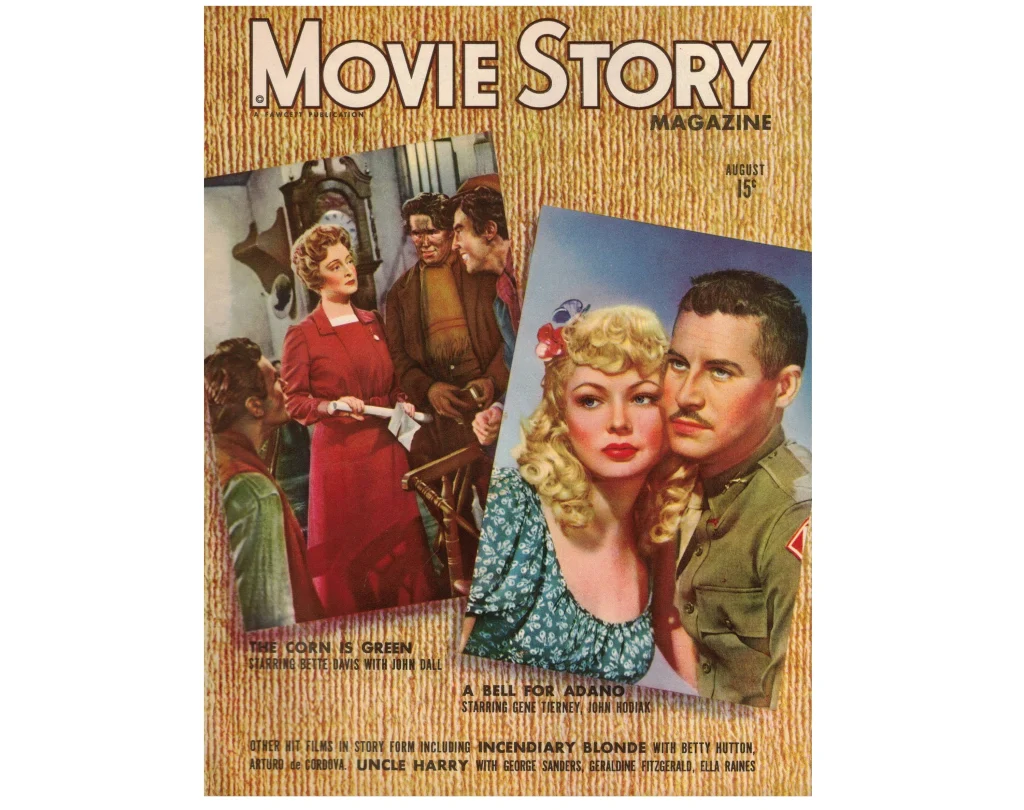

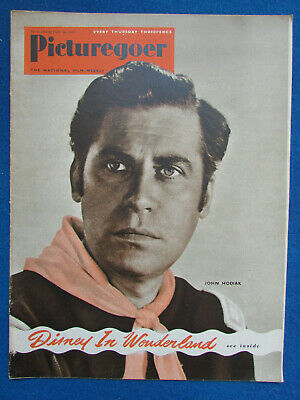

John Hodiak was born in 1914 in Pittsburgh. He came to fame with Alfred Hitchcock cast in “Lifeboat” in 1944. He starred opposite Gene Tierney in “A Bel for Adano”, opposite Judy Garland and Angela Lansbury in “The Harvey Girls” and “Battleground”. He died suddenly at the age of 41 in Tarzana, California in 1955.

Gary Brumburgh’s entry:

Pittsburgh-born John Hodiak was one of several up-and-coming male talents who managed to take advantage of the dearth of WWII-era superstars (MGM’s Clark Gable,Van Johnson, Robert Taylor and James Stewart, among others) who were off serving their country. John’s early death at age 41, however, robbed Hollywood of a strong player and promising character star.

Born on April 16, 1914, the eldest of four (one daughter was adopted), John was eight years old when his middle-class family moved to a thriving Polish community in a suburb of Detroit, Michigan. His father, Walter, was born in the Ukraine and his mother, Anna, was Polish. Expressing interest in music and drama at an early age, he was encouraged by his father who had appeared in amateur shows. He found roles in school plays (done in Hungarian or Polish), sang in the Ukranian church choir, played the clarinet, and even took diction lessons. Not to be outdone, his athletic skills were also put on display. At one point, he was considered by the St. Louis Cardinals for their farm league but he declined the offer in favor of pursuing an acting career.

Following high school, John found work as a golf caddy and stockroom clerk (at a Chevrolet company) before breaking into radio (WXYZ) in Detroit and (later) Chicago. His more notable roles was as the title figure in “L’il Abner” (a role created on radio) and in the serials “Ma Perkins” and “Wings of Destiny”. While in Chicago he was noticed by MGM talent agent Marvin Schenck and signed. Proud of his heritage, he refused to change his name to a more marquee-friendly moniker despite mogul Louis B. Mayer‘s concerns. Hodiak made his debut as a walk-on in A Stranger in Town (1943), and had a bit part in one of Ann Sothern‘s “Maisie” series Swing Shift Maisie (1943) before becoming her leading man in a subsequent entry (Maisie Goes to Reno (1944)) the following year.

His inability to sign up for military duty due to his high blood pressure ended up giving him a starring career. Attention started being paid after he played Lana Turner‘s soldier husband in Marriage Is a Private Affair (1944). An interested Alfred Hitchcock then borrowed John for the role of Kovac, the torpedoed ship’s crew member, in one of his classic war dramas Lifeboat (1944) starring the irrepressible Tallulah Bankhead at 20th Century-Fox. The studio was so impressed with John’s work in this that it cast him in two other quality films: Sunday Dinner for a Soldier (1944) and A Bell for Adano (1945), both of which showed off his quiet but rugged charm.

In the former he played the patriotic title role and co-starred with Anne Baxter. No sparks as of yet between these two, but a year or so later they reconnected at a party and started dating. They married on July 6, 1946. The second film, the exquisitely sensitive and moving war picture A Bell for Adano (1945) made him a star by Hollywood standards. Co-starring a rather miscast Gene Tierney (as a blonde Italian village girl) andWilliam Bendix, John was more than up to the challenge of playing the role of U.S. Major Joppolo, originally created on Broadway by Fredric March. The irony of it all is that the actor never found better roles (at MGM) than the ones he filmed while lent out to Fox.

Back at MGM, John went through the usual paces. He was overlooked in the rousing Judy Garland vehicle The Harvey Girls (1946), but seemed much more at home in the film noirSomewhere in the Night (1946) and in the WWII drama Homecoming (1948) that starredClark Gable and Lana Turner, with John and wife Anne Baxter serving as second leads.

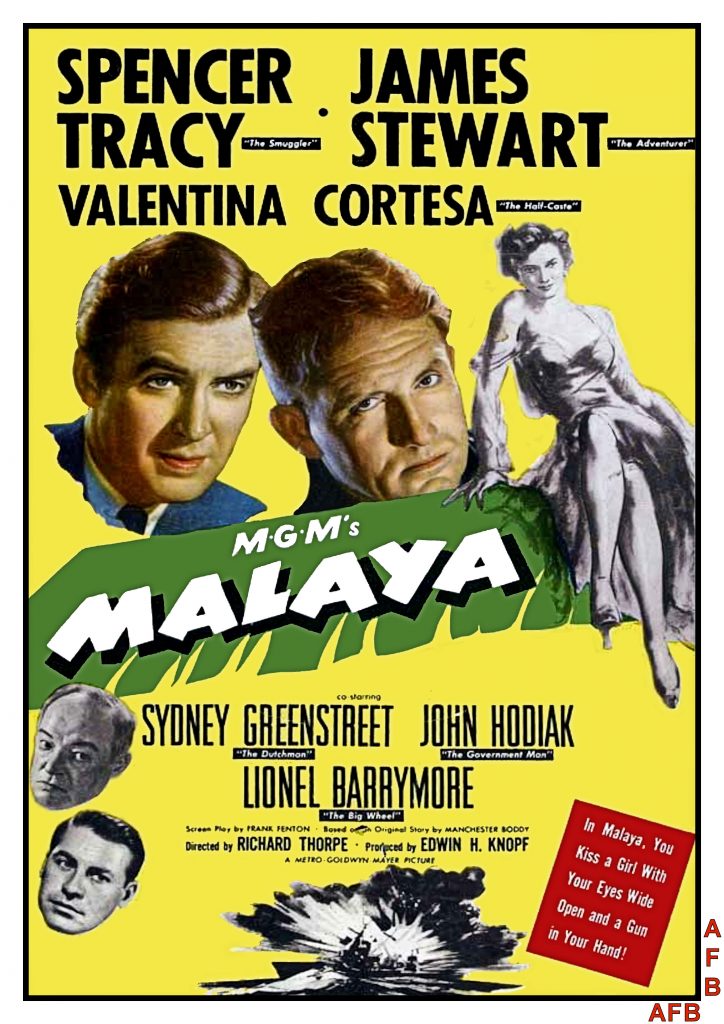

With MGM’s male roster of talent back home now from the war, John was unceremoniously relegated to second leads that supported the top-tier actors, including Gable, Spencer Tracy, Robert Walker, James Stewart and Robert Taylor. While several of his subsequent post-war films drew desultory reviews, notably the Greer Garson “Miniver” sequel The Miniver Story (1950), Hedy Lamarr‘s so-called tale of intrigue A Lady Without Passport (1950), and the Clark Gable western Across the Wide Missouri (1951), John did manage to co-star in two of MGM’s more stirring war pictures — Command Decision(1948) and Battleground (1949). Occasionally deemed “glum” and “wooden” by his harsher critics, John’s MGM contract expired in 1951 and he began to freelance. Most of the work that followed were starring roles in low-budget entries. Battle Zone (1952) had John and Stephen McNally as two Korean war photographers distracted by the lovelyLinda Christian, and Conquest of Cochise (1953) featured a miscast John as the famed Indian warrior.

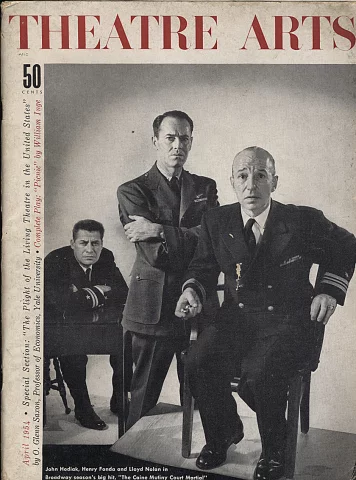

John reaped better rewards on the stage during this time. Receiving excellent reviews following his 1952 Broadway debut as the sheriff in “The Chase” (he received the Donaldson Award), the actor returned to Broadway as Lieutenant Maryk in “The Caine Mutiny Court Martial (1954) co-starring Henry Fonda. He was extremely disappointed when former fellow MGM player Van Johnson was cast as the lieutenant in the acclaimed film version starring Humphrey Bogart as Captain Queeg.

The father of daughter Katrina Baxter Hodiak, who was born in 1951, John and Anne’s varied backgrounds (he was middle class and she more high society — her grandfather being the renowned Frank Lloyd Wright) and their busy film careers created significant problems. They divorced on January 27, 1953. John later built a home for his parents and younger brother in Tarzana, California and eventually lived there with them. His later years grew difficult and were plagued by self-doubt, a diminishing career and an equally diminishing social life.

John’s key Broadway success in “Mutiny” led to a fine comeback role on screen as a prosecuting attorney in Trial (1955), finding “guest artist” work on dramatic TV as well. What might have led to a strong resurgence, however, was sadly cut short. On the morning of October 19, 1955, 41-year-old John suffered a coronary thrombosis and died instantly while shaving in the bathroom of his home. He was on his way to the 20th Century-Fox lot to complete final work on his last film, On the Threshold of Space (1956), when he was stricken.

The movie was released posthumously with John’s role left intact. No previous record of a heart ailment was ever uncovered. It was an extreme shock to lose someone so relatively young, and even sadder for those he loved and left behind, including his 4-year-old daughter. Katrina Hodiak later became a composer, an actress and a theater director). John was interred at the Calvary Cemetery in Los Angeles.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net

John Agar was born in 1921 in Chicago, Illinois. He starred with John Wayne in six movies, “Sanda of Iwo Jima” and John Ford’s “She Wore a Yellow Ribbon”, “Big Jake”, “Chisum”, “Ford Apache with Shirley Temple to whom he was married for a time and “The Undefeated”. He died in 2002 at the age of 81.

Ronald Bergan’s obituary in “The Guardian”:

The American film actor John Agar, who has died aged 81, was famous in different quarters for different things; his well-publicised marriage to Shirley Temple and his subsequent alcoholism; his appearance in two of John Ford’s best westerns – Fort Apache and She Wore A Yellow Ribbon – and, later, as the star of dozens of cheesy but cultish science-fiction B-movies.

Agar was a tall, handsome, 24-year-old US Army Air Corps sergeant and physical education instructor, when, in early 1944, a friend arranged for him to escort the 16-year-old Temple to a Hollywood party given by her boss, David O Selznick. They married a few months later in front of gossip columnists from all over the world and thousands of screaming fans.

For the next few years, the glamorous couple – he was the scion of an old Chicago meat-packing family – were seldom out of the screen magazines, which included pictures of them posing blissfully with their baby daughter Linda Susan, born in January 1948. By the end of the following year, however, troubled by her husband’s excessive drinking – he had been arrested for drunken driving – and his philandering, Temple filed for divorce.

With his career on the skids, Agar joined Alcoholics Anonymous, remarried and tried to remake himself by keeping a straight face amid campy situations in films such as The Revenge Of The Creature, Tarantula (both 1955), The Mole People (1956), The Brain From Planet Arous (1957) and The Attack Of The Puppet People (1958).

These enjoyably ridiculous low-budget pictures contrasted greatly with the films he made in the 1940s. Before Selznick signed him for a five-year contract at $150 a week, with acting lessons thrown in, Agar had made his screen debut opposite his young wife in Fort Apache (1948), in which Henry Fonda’s martinet colonel refuses to allow his daughter (Temple) to marry the non commissioned Lieutenant O’Rouke (Agar). Nonetheless, the on-screen love affair blossoms, reflecting what audiences wanted to believe was the pair’s true-life romance.

The following year, they co-starred in an anti-feminist comedy, Adventure In Baltimore. Agar then appeared as another naive but brave young officer in She Wore A Yellow Ribbon (1949), vying humorously with Harry Carey Jr for the hand of Joanne Dru, under the fatherly eye of John Wayne.

He was with Wayne again in The Sands Of Iwo Jima (1949), as a cocky recruit with an axe to grind; when Wayne dies, Agar grimly leads his men forward. Two decades later, Wayne gave him small roles in The Undefeated (1969), Chisum (1970) and Big Jake (1971).

Among Agar’s other westerns were Along The Great Divide (1951), giving good support to Kirk Douglas, and Star In The Dust (1956), in which he got top billing as a sheriff battling to convince the townsfolk of his methods. Many more movies followed until his last appearance, in Miracle Mile (1989). He then became a popular guest at US science-fiction conventions.

Agar is survived by his daughter, and the two sons of his second marriage, to former model Loretta Combs, who died in 2000.

John Agar, film actor, born January 31 1921; died April 7 2002

Nancy Kelly was born in 1921 in Lowell, Massachusetts. She was the sister of Jack Kelly who starred with James Garner in “Maverick”. Her films include “Jesse James” with Tyrone Power in 1939, “Murder in the Music Hall” with Vera Ralston in 1945 and repeated her Broadway success in “The Bad Seed” in 1956. She died in 1995 aged 73.

Dick Vosburgh’s obituary in “The Independent”:

Although she made more than 30 films and received an Academy Award Best Actress nomination, Nancy Kelly’s greatest triumphs were in the theatre.

One of New York’s most successful child models from infancy, she made her first appearance on the Broadway stage at the age of 10 in Give Me Yesterday (1931). A role in Rachel Crothers’s Susan and God (1937), which ran for two seasons on Broadway with Gertrude Lawrence heading the cast, led to a 20th-Century Fox screen-test for Kelly, swiftly followed by a long-term contract and a leading role in John Ford’s Submarine Patrol (1938). Frank S. Nugent wrote in the New York Times: “Here’s a morning g un forNancy Kelly, who has the responsibility of being the only girl in the cast, not merely by being as decorative as she is, but with a charming and assured performance. Miss Kelly bears watching; in fact, it will be a pleasure.”

A year later, the same paper’s Bosley Crowther was equally enamoured of Kelly, to the extent that he actually forgave Fox for crowbarring her into Stanley and Livingstone as the patently fictitious object of Henry Morton Stanley’s affection. “We don’t see,” he wrote, “how any one could be so officious as to demand that the presence of an actress so charming must also be supported by documents.”

Despite effusions from critics, Fox assigned Kelly a pallid “Outlaw’s Noble Wife” role in Jesse James (1939), put her into minor fluff like He Married His Wife and Sailor’s Lady (both 1940), and loaned her out for the likes of One Night in the Tropics and Parachute Battalion (both 1941). Her last film for 20th Century-Fox was To the Shores of Tripoli (1942) in which the studio showed its indifference by letting her lose John Payne to Maureen O’Hara.

A return to Broadway to play Alec Guinness’s wife in Terence Rattigan’s London success Flare Path (1942) was a disappointment; the play ran only three weeks. In Tarzan’s Desert Mystery (1943), Kelly was cast as a wisecracking vaudeville magician in a plot that also found room for Nazis, giant spiders, sinister Arabs and dinosaurs. In Show Business (1944) she played a scheming burlesque performer, hell-bent on breaking up the marriage of George Murphy and Constance Moore. Such was the skill of her actingthat she actually managed to simulate convincing lust for Murphy.

After a handful of films in which she was paired with such fading leading men as William Gargan, Lee Tracy and Chester Morris, Kelly returned to Broadway. Her experience with the studios could only have helped her performance as John Garfield’s Hollywood-hating wife in Clifford Odets’s searing play The Big Knife (1949). Four years later she played another tortured Odets wife in a tour of The Country Girl. Her performance as the agonised mother of an eight-year-old murderess in Maxwell Anderson’s Broadwa y hit The Bad Seed (1954-55) won her a Tony Award. Two years later Kelly and other key members of the New York cast journeyed west to make the screen version. She received her Oscar nomination for her work in the film.

Kelly twice received the Sarah Siddons Actress of the Year Award in a theatre career that embraced such disparate playwrights as Shakespeare, Neil Simon and Edward Albee. Her television work included Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Climax and The Pilot (1956), a TV biography of Sister Mary Aquinas, a noted educator and the first nun to be granted a pilot’s licence. Variety reported: “Miss Kelly humanised Sister Mary and made a colourful, interesting and touching character out of her.” For this performance, Nancy Kelly added an Emmy Award to her crowded mantelpiece.

The above “Independent” obituary can be accessed online here.

Anyone who knows me are aware that I am a bit of a movie buff. Over the past few years I have been collecting signed photographs of my favourite actors. Since I like movies so much there are many actors whose work I like.