Kurt Russell starred in one of my favourite movies “Escape from New York” in 1981. He began his career as a child actor and was featured in “It Happened At the World’s Fair” in 1962 with Elvis Presley. His other movies include “Swing Shift” with his partner Goldie Hawn and “Guns in the Heather” which was made in the West of Ireland for Walt Disney.

TCM overview:

After getting his start as a child star in several movies for Walt Disney Studios, actor Kurt Russell managed to shed his wholesome image to play some of cinema’s most notorious and hard-edged tough guys. Russell first broke the Disney mold with an acclaimed portrayal of the King in the made-for-television biopic, “Elvis” (ABC, 1979), which many hailed as one of the finest performances of his career. Having partnered with director John Carpenter, he next essayed one of his most enduring characters, Snake Plissken, the antihero of Carpenter’s cult classic “Escape from New York” (1981). Russell delivered another solid performance as memorable hard-case R.J. MacReady in Carpenter’s gory remake of “The Thing” (1982). While making the troubled romantic comedy, “Swing Shift” (1984), Russell became romantically involved with co-star Goldie Hawn, with whom he forged a lasting partnership that resembled a marriage, but without the actual legal certificate. He was even considered by Hawn’s two children from a previous marriage, actress Kate Kudston, and her brother, Oliver, to be – at least in spirit – their father. Meanwhile, Russell thrived throughout the 1980s with “Big Trouble in Little China” (1986) and “Tequila Sunrise” (1988), which carried over into the next decade with “Backdraft” (1991), “Captain Ron” (1992) and a dead-on portrayal of Wyatt Earp in “Tombstone” (1993). Following box office success with “Stargate” (1994) and “Executive Decision” (1996), Russell offered up his most engaging performance in the tense thriller “Breakdown” (1997). Though he later faltered with “3000 Miles to Graceland” (2001) and “Poseidon” (2006), Russell nonetheless remained one of the most engaging actors in Hollywood.

Born on March 17, 1951 in Springfield, MA, Russell was later raised in Thousand Oaks, CA by his mother, Louise, a dancer, and his father, Bing, a character actor best known for playing Deputy Clem Foster on “Bonanza” (NBC, 1959-1973). Growing up around the entertainment industry gave the young Russell an opportunity to appear onscreen himself. Russell made his first television appearance with a guest starring role on the short-lived sitcom “Our Man Higgins” (ABC, 1962-63) before turning to hour-long drama with an episode of “The Eleventh Hour” (NBC, 1962-64). In short order, Russell found himself starring in his own series, “The Travels of Jaimie McPheeters” (ABC, 1963-64), in which he played the titular role of a 12-year-old boy who depicts his experiences with his family and the hardships faced after settling California in 1849. Following the cancellation of that series, the young actor appeared as a guest star on shows like “The Virginian” (NBC, 1962-1971) and “Gilligan’s Island” (CBS, 1964-67), before making his feature debut in “Follow Me, Boys!” (1966), one of several pictures for Walt Disney made by Russell early in his career. He played a Boy Scout who befriends a traveling saxophonist (Fred McMurphy) settling down in his small Midwestern town.

Russell continued making films for Disney with a supporting role in “The Horse in the Gray Flannel Suit” (1968), followed by a starring role in “The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes” (1970), in which he played Dexter Riley, a student whose brain becomes a virtual hard drive after a computer he was trying to fix is struck by lightning. He revived the same character, now turned college student, who invents an invisibility spray coveted by a gang of thieves in the pseudo-sequel, “Now You See Him, Now You Don’t” (1972). As he entered his twenties, Russell made his last pictures with Disney – “Charley and the Angel” (1973) and “Superdad” (1974), co-starring Bob Crane – before making his final Disney movie under contract with “The Strongest Man in the World” (1975), playing for the last time troublesome college student Dexter Riley. He began making the segue to more adult roles with two failed series, “The New Land” (ABC, 1974) and “The Quest” (NBC, 1976), and completely shedding his nice kid image with a chilling portrayal of mass-murderer Charles Whitman in the television movie, “The Deadly Tower” (NBC, 1975).

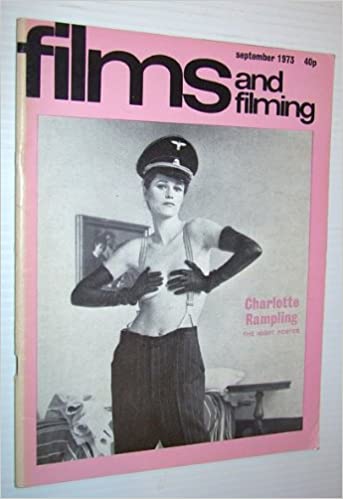

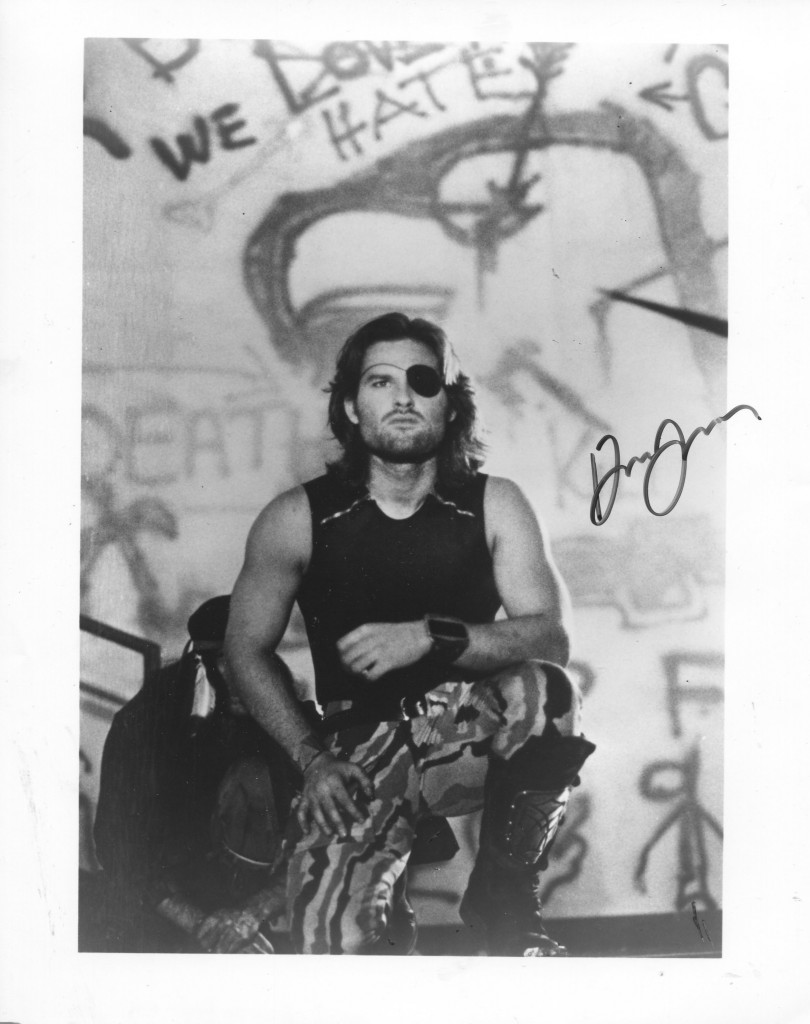

A few years later, Russell delivered a career-defining performance as the King of Rock and Roll in director John Carpenter’s television biopic, “Elvis” (ABC, 1979). Though low-budget and missing certain key details, Carpenter’s movie opened to huge ratings and earned Russell an Emmy Award nomination, whole touching off a fruitful collaboration between actor and director over the next decade. Russell also married co-star, Season Hubley, who played Priscilla Presley, after the couple displayed undeniable chemistry onscreen. On the big screen, he became a bankable adult Hollywood star, thanks to a fine performance as a fast-talking charmer in Robert Zemeckis’ raucous, under-appreciated comedy, “Used Cars” (1980). He experienced greater popular success by reuniting with Carpenter for the cult classic sci-fi actioner, “Escape From New York” (1981), playing eye-patched antihero, Snake Plissken, a former solider-turned-criminal in a dystopian future where Manhattan has been turned into a maximum security prison, who is backed into saving the President of the United States (Donald Pleasence) after Air Force One crash lands on the island. Made on a shoestring budget of $6 million, “Escape” earned over $50 million at the box office. It also ushered in a new career trajectory for Russell, who managed to shed his family-friendly image from the previous decade for good.

After voicing the adult hound dog Copper in “The Fox and the Hound” (1981) for his former employer, Walt Disney Studios, Russell reunited with Carpenter for “The Thing” (1982), a gory remake of Howard Hawks’ 1951 film about a 12-man rescue team that discovers a parasitic alien life form that had been buried beneath the Earth for 100,000 years. Though admired by some critics despite the film’s excesses of violence and gore, “The Thing” wound up being a box office failure. It did, however, live on as another cult classic, while adding on to Russell’s impressive array of big screen tough guys. He next co-starred in Mike Nichols’ somber biopic, “Silkwood” (1983), playing the lover of nuclear plant work, Karen Silkwood (Meryl Streep), whose mysterious car accident death after her groundbreaking investigation into plant safety led to a reexamination of nuclear energy. Meanwhile, Russell took a turn toward romantic comedy with a co-starring role opposite Goldie Hawn in “Swing Shift” (1984), in which he played a factory worker denied enlistment during World War II, who falls for a woman (Hawn) working the production line while her husband is off fighting in Europe. Though conventional onscreen, “Swing Shift” was noted for the behind-the-scenes battles between Hawn, who also served as producer, and director Jonathan Demme over the film’s tone. It also marked the beginning of a long-running companionship between Russell and Hawn; though they never married, the couple remained a steadfast couple for several decades while Russell was considered by Hawn’s children, Kate Hudson and Oliver Hudson, to be their father, even though they were never legally adopted by him.

Following a starring turn opposite Mariel Hemingway in the psychological thriller, “The Mean Season” (1985), Russell teamed up again with John Carpenter for “Big Trouble in Little China” (1986), doing a hilarious John Wayne-like turn as a tough-guy truck driver who tries to save his friend’s fiancée (Suzee Pai) from an ancient sorcerer (James Hong) hiding beneath San Francisco’s Chinatown. He next played a former star high school quarterback-turned-garage owner coaxed back into reigniting an old gridiron rivalry by a teammate (Robin Williams) in “The Best of Times” (1986). In their first film as a famous Hollywood couple, Russell and Hawn starred in “Overboard” (1987), a screwball comedy about a snobby heiress (Hawn) with amnesia who is tricked by a disgruntled carpenter (Russell) into believe she is his wife and the mother of four rambunctious boys, leading her to a hectic life of cleaning and cooking. Though not a major success, the film enjoyed a hefty video rental life and became something of a guilty pleasure for fans of silly but charming romantic comedies. Russell followed up by playing a celebrity cop who falls for the same woman (Michelle Pfeiffer) as his life-long friend – a retired drug dealer (Mel Gibson) – in Robert Towne’s hit crime drama, “Tequila Sunrise” (1988).

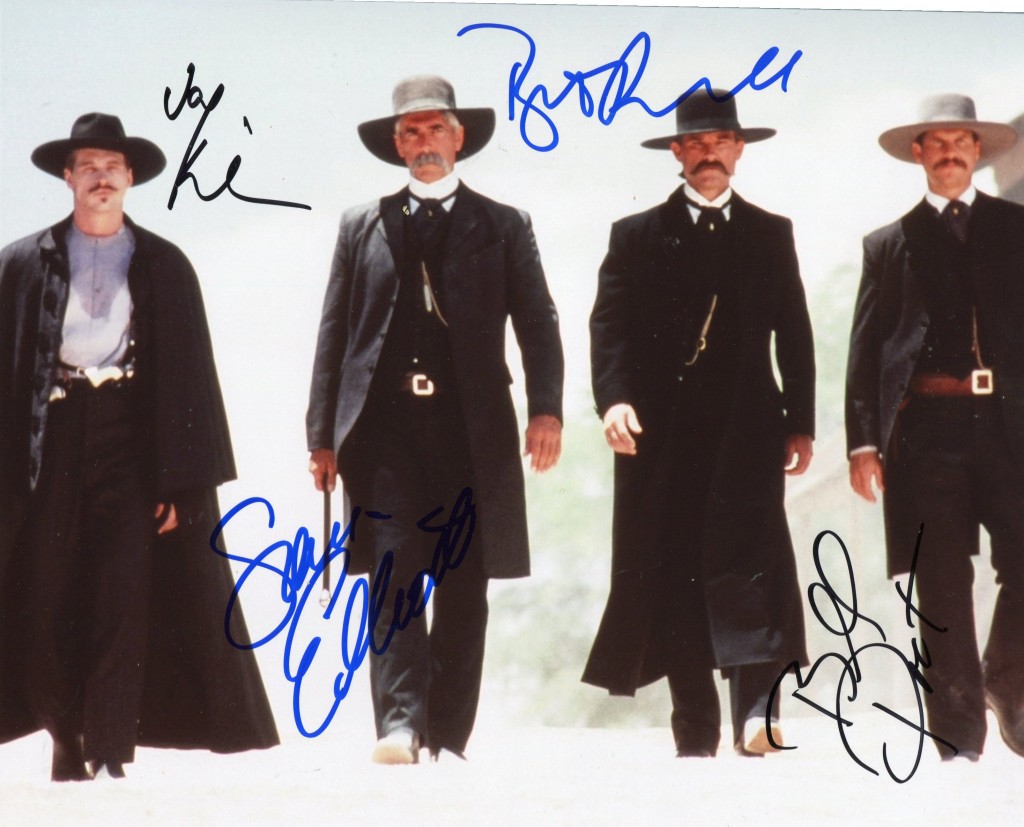

Russell received some of his worst reviews of his career with his next feature, “Tango & Cash” (1989), a buddy action comedy which paired him opposite Sylvester Stallone, as both are set-up for a crime they did not commit by a notorious drug dealer (Jack Palance). Panned by critics, the movie also earned Russell the first Razzie award nomination of his career, thanks to a scene in which he dressed in drag. Russell rebounded quite well with his next film, director Ron Howard’s “Backdraft” (1991), playing a stalwart firefighter who is suspected of being an inside man during a series of arsons investigated by a dogged fire inspector (Robert De Niro). He next played the crusty, seafaring “Captain Ron” (1992), who takes the family of a beleaguered Chicago businessman (Martin Short) on a cruise from the Caribbean. Noted for its finely-tuned comic performance from Russell and numerous quotable lines, “Captain Ron” earned status as a yet another Russell cult hit. After a good turn as a husband terrorized by a crazed cop (Ray Liotta) in “Unlawful Entry” (1992), Russell delivered his most convincing performance then to date in “Tombstone” (1993), playing famed U.S. Marshal Wyatt Earp, whose involvement in the shootout at the O.K. Corral became the stuff of Old West legend.

Though the movie itself was successful with both critics and audiences, “Tombstone” was plagued with problems during production, especially when original director, Kevin Jarre, was fired for refusing to cut down an over-long script. Though the rest of the film was helmed by George P. Cosmatos, Russell had claimed – especially in later years – to have directed some scenes himself. He delivered another memorable tough-guy turn in “Stargate” (1994), an action sci-fi combo in which he played a suicidal colonel teamed up with a nerdy Egyptologist (James Spader) to explore another world reached by an ancient cosmic traveling device. Following a reprisal of sorts in voicing Elvis for a brief scene in “Forrest Gump” (1994), Russell starred in the political thriller “Executive Decision” (1996), in which he portrayed a military intelligence analyst who tries to save 400 passengers aboard a hijacked 747. After a good 15 years, Russell once again played futuristic antihero Snake Plissken in John Carpenter’s follow-up, “Escape from L.A.” (1996). Despite the hype surrounding the reprisal, the film failed to live up to expectations, while also having a poor run at the box office. Aside from his starring role, Russell also served as a producer and co-screenwriter.

Russell delivered a good performance in the surprisingly tense Hitchcockian thriller, “Breakdown” (1997), playing a desperate husband trying to find his wife (Kathleen Quinlan), who was mysteriously kidnapped after their jeep breaks down in the middle of the New Mexico desert. Following this compelling addition to his oeuvre, Russell began appearing in a string of disappointing films that pushed him further and further from the public’s consciousness after spending a better part of his career at the forefront of Hollywood’s most bankable stars. He starred in the critically panned box office flop, “Soldier” (1998), playing a genetically enhanced officer tasked with protecting an innocent civilian village in a distant galaxy from being destroyed. Following a small role as a court psychologist in the Cameron Crow misfire “Vanilla Sky” (2001), Russell made another questionable choice by starring opposite Kevin Costner in “3000 Miles to Graceland” (2001), a much-maligned caper movie in which Russell revisited his Elvis roots by dressing up as the King alongside his partner in crime (Costner) to pull off a heist at a Las Vegas casino.

In 2003, Russell co-starred in the emotionally charged, James Ellroy’s adaptation, “Dark Blue,” playing a streetwise, but corrupt police veteran in Los Angeles during the 1992 riots. Russell delivered a commanding performance in the controversial, gray-shaded role and carried the movie on his shoulders until the plot gave way to conventional thriller territory. He again had a strong turn in “Miracle” (2004) playing Herb Brooks, the real-life coach of the United States Olympic hockey team; the same Cinderella team that pulled off the unimaginable defeat of the dominating teams from the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia. Russell, an avid hockey enthusiast himself, practically channeled the complicated Brooks and delivered another knockout performance. Russell’s next effort was not as winning, however, though he did deliver his trademark charm in the superhero spoof “Sky High” (2005), in which he played Captain Stronghold, a super-powered father who sends his non-powered son (Michael Angarano) to a secret academy for superhero offspring. He next had a turn in the family film “Dreamer: Inspired by a True Story” (2005), playing a once gifted horseman who is given a lame horse and takes the mare on a quest to win the Breeders Cup Classic, thanks to the unwavering determination of his young daughter (Dakota Fanning).

After turning in several fine, low-key performances, Russell tried to step back into the limelight with the larger-than-life remake, “Poseidon” (2006), playing a middle-aged father struggling to escape a capsized ocean liner with a ragtag group of passengers. But “Poseidon” sank at the box office, leaving Russell still attempting to recapture past box office glory. In a hat-tip to Snake Plissken and other onscreen bad-asses of films past, Russell was a sadistic stunt driver named Stuntman Mike in the Quentin Tarantino-Robert Rodriguez double bill “Grindhouse” (2007). A compilation of two 90-minute horror flicks from both directors, “Grindhouse” was a throwback to the days of bloody, sex-fueled, low-rent double features that played in seedy 42nd Street theaters in New York City. In Tarantino’s offering, a slasher-cum-road rage flick called “Death Proof,” Russell was a crazed killer who tries to mow down young women – including Rosario Dawson and Zoë Bell – in a black Chevy Nova. Though unsuccessful at the box office, “Grindhouse” – which included the Rodriguez portion, “Planet Terror,” and fake movie trailers – was embraced by a majority of critics.