Russell Todd was born in 1958 in Albany, New York. He made his movie debut in 1980 in “He Knows You’re Alone”. Other movies include “Friday the 13th part Two” and “Chopping Mall”. Now retired from acting, his last movie was in 1996.

Hollywood Actors

Russell Todd was born in 1958 in Albany, New York. He made his movie debut in 1980 in “He Knows You’re Alone”. Other movies include “Friday the 13th part Two” and “Chopping Mall”. Now retired from acting, his last movie was in 1996.

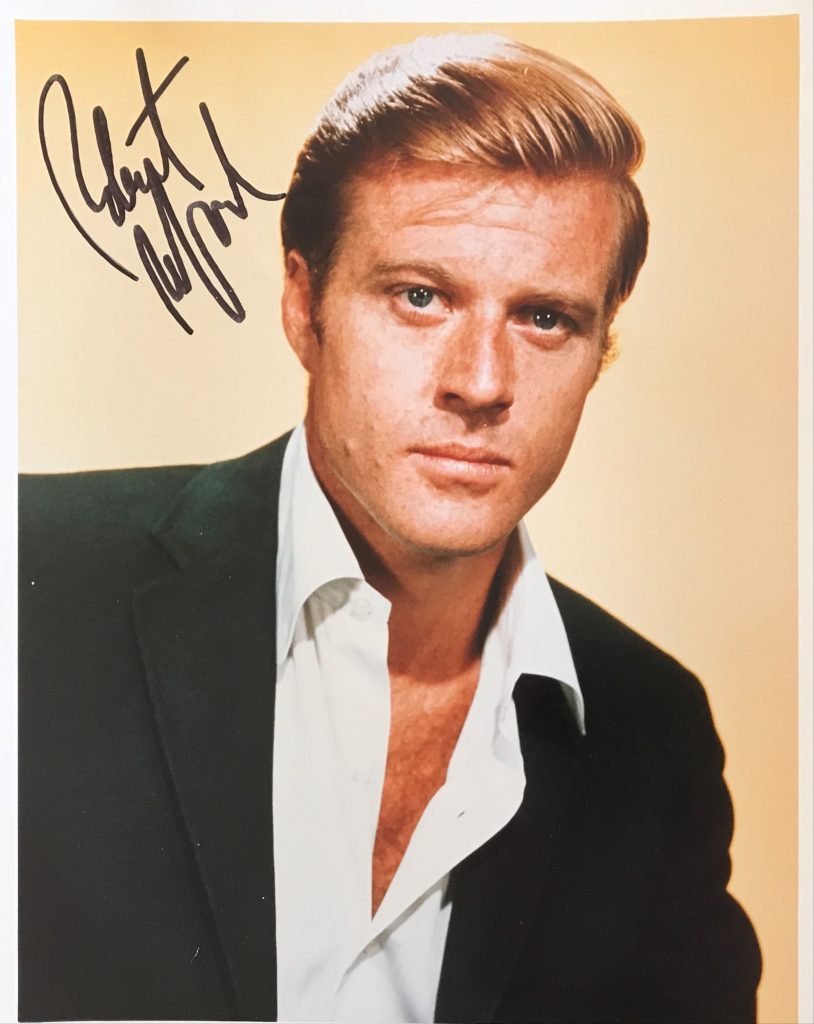

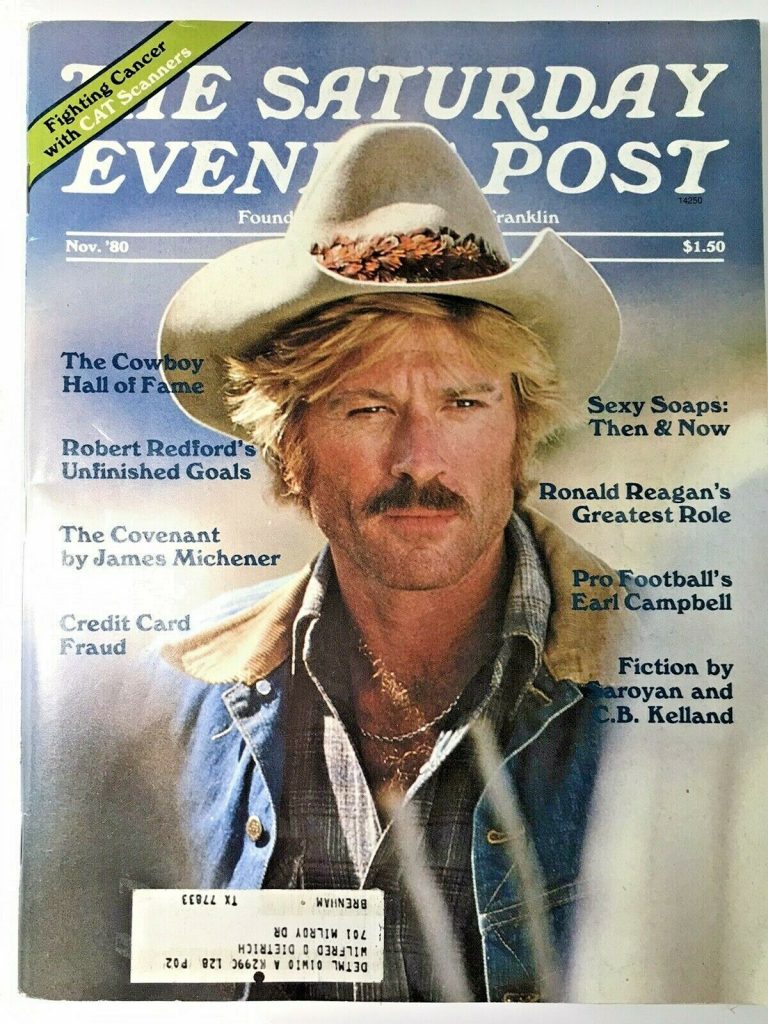

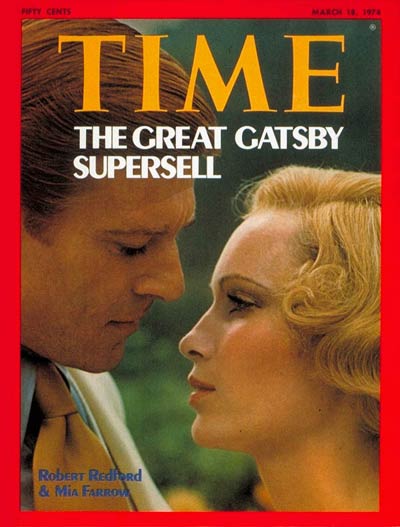

Robert Redford(born August 18, 1936),[ is an American actor, film director, producer, businessman, environmentalist, philanthropist, and founder of theSundance Film Festival. He has received two Oscars: one in 1981 for directing Ordinary People, and one for Lifetime Achievement in 2002. In 2010 he was awarded French Knighthood in the Legion d’Honneur. At the height of Redford’s fame in the late 1960s to 1980s, he was often described as one of the world’s most attractive men and remains one of the most popular movie stars.

TCM overview:

Robert Redford’s all-American blond good looks and subtle, sardonic sense of humor made him one of the most popular leading men of the late 1960s into the 1970s in features like “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969), “The Sting” (1973) and “All the President’s Men” (1976). Along with his peers Warren Beatty and Paul Newman, he was one of the rare movie icons who could balance being both a respected actor as well as undeniable sex symbol – seen most effectively with his heartfelt turn in “The Way We Were” (1973) – a timeless romance which caused many a female heart to flutter through the years. Growing into his age gracefully, he branched out, wisely parlaying his acting fame into an Oscar-winning career as a director, and becoming a patron saint of sorts to independent filmmakers by establishing the Sundance Film Festival and Sundance Institute, as well as numerous critically acclaimed projects that supported original moviemaking outside the Hollywood system.

Redford’s early years showed a distinct rebellious streak that carried well into adulthood. The son of a Standard Oil accountant, Charles Robert Redford, born Aug. 18, 1936, lost his mother while still in his teens, which spurred a rash of adolescent misdemeanors, as well as the loss of a baseball scholarship to the University of Colorado due to alcohol-related infractions. He departed the school in 1957 to attend the Pratt Institute of Art before taking a tour of Europe to explore his painterly side. He returned to the States and promptly decided on a career in acting, which he studied at the acclaimed American Academy of Dramatic Arts. In 1958, Redford married Lola Van Wagenen, with whom he had four children between 1959 and 1970 (the first, Scott, died from Sudden Infant Death Syndrome in 1959).

Redford’s tall frame and physical appeal made him a natural for television and theater producers looking for upstanding young men, so he found himself working regularly on quality shows like “Playhouse 90” (CBS, 1956-1961), in which he appeared in the series’ finale episode, Rod Serling’s “In the Presence of Mine Enemies;” Sidney Lumet’s TV presentation of “The Iceman Cometh” (1960) with Jason Robards; as well as quick paychecks like the game show “Play Your Hunch” (NBC, 1960-1962). He also worked extensively on stage during this period, with his Broadway debut coming in 1959’s “Tall Story” (he also had an uncredited role in the 1960 film version) and he eventually worked his way up to major productions like Neil Simon’s “Barefoot in the Park” in 1963.

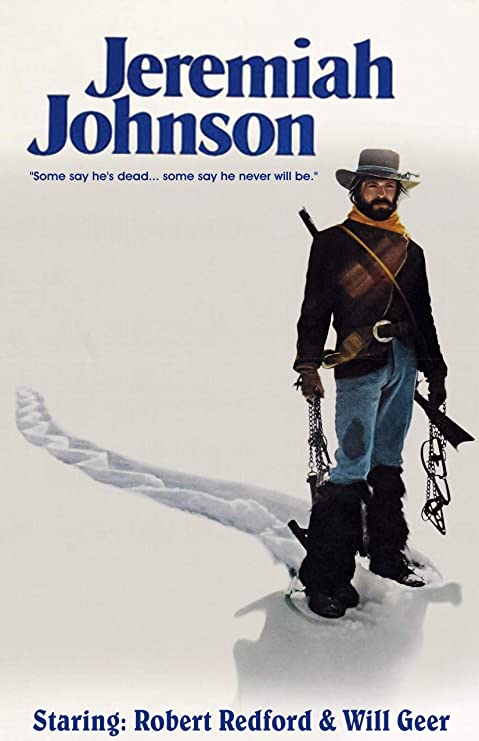

An Emmy nod for an episode of “Alcoa Premiere” (NBC, 1961-63) preceded his first substantial film role in “War Hunt” (1962), a Korean War drama about a psychotic soldier (John Saxon) in an Army platoon. Also making his debut in the project was future filmmaker Sydney Pollack, a longtime friend of Redford’s and his director on several projects, including “Jeremiah Johnson” (1972) and “The Way We Were.” More television followed – including three stints on “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” (NBC, 1955-1965); “The Twilight Zone” (CBS, 1959-1964) in a memorable turn as the Angel of Death; and “The Defenders” (CBS, 1961-65) – but he graduated to regular film work after his success in “Barefoot in the Park.” What followed was a string of roles in solid if unremarkable features that played up Redford’s looks rather than his talent. He was a ’30s-era movie star and closeted homosexual in “Inside Daisy Clover” (1965); a Southern prison escapee targeted by a conflicted sheriff (Marlon Brando) in Arthur Penn’s “The Chase” (1966); and a railway representative who falls for a flirtatious Natalie Wood in “This Property Is Condemned” (1966), with Francis Ford Coppola adapting the Tennessee Williams play for director Sydney Pollack.

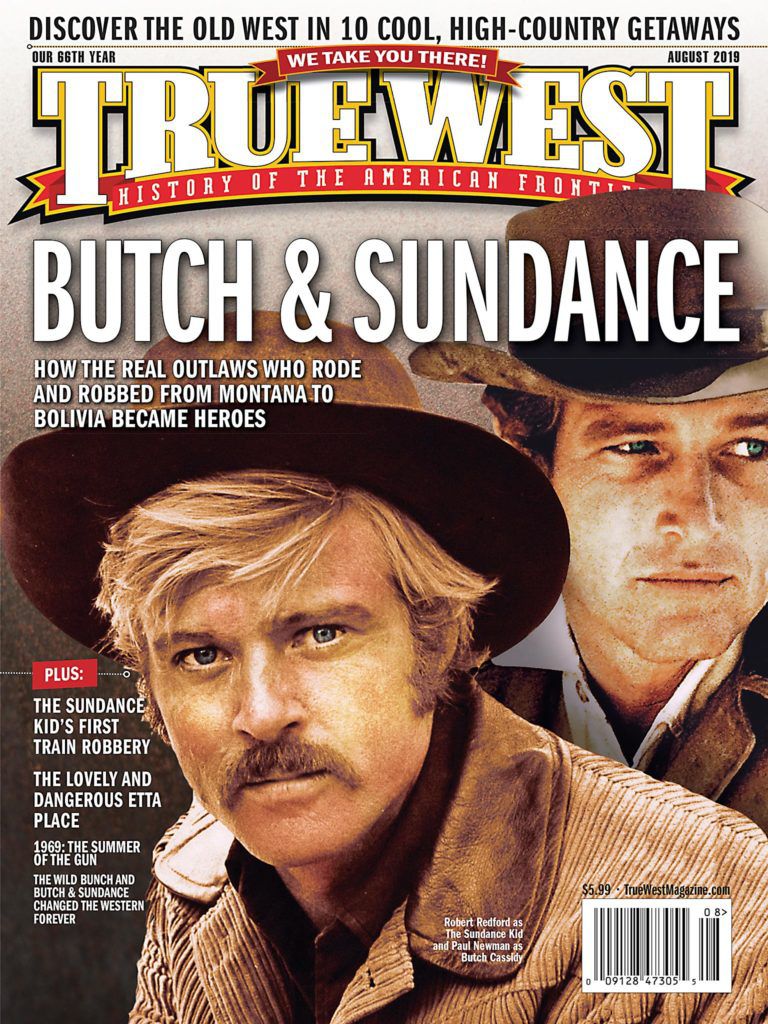

Sensing that his career was heading into stagnant waters, Redford decided to pass on projects like “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” (1966) and “The Graduate” (1967) – both of which would have perpetuated his streak of bland leading men; Redford was holding out for something more substantial. His deliverance came in the form of George Roy Hill’s Western adventure, “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969), which partnered him with Paul Newman as the rowdy title outlaws. Redford was not favored for the role by 20th Century Fox, but Hill was adamant about him in the role of the Sundance Kid. The result was a blockbuster hit and a multiple Oscar winner, as well as the second act of Redford’s career. His turn as the breezy, death-defying Kid redefined his screen persona, and gave him a name on which to hang many of his future endeavors.

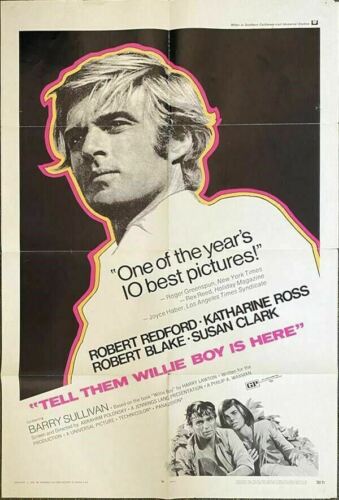

After “Sundance,” Redford embarked on a personal crusade to participate in projects that emphasized quality over concept and star power. His efforts to this end, while not always successful at the box office, were a remarkable string of mature and involving dramas, including “Downhill Racer” (1969), with Redford as an egotistical skier who clashes with coach Gene Hackman (Redford also served as executive producer); “Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here” (1969), with Redford as a sheriff on the trail of Indian Robert Blake, who has killed his white lover’s father; and “Little Fauss and Big Halsey” (1970), with Redford and Michael J. Pollard as motorcycle racers. “The Hot Rock” (1972) was a breezy comedy based on a Donald Westlake novel, with Redford leading an inept team of jewel thieves, but it failed to score with audiences. More successful was “Jeremiah Johnson,” a fact-based Western for Sydney Pollack about a vengeful mountain man (Redford) hunting the Indian tribe that butchered his family, and “The Candidate” (1972), a darkly comic political satire about a lawyer (Redford) corralled into running for a senatorial seat by a savvy campaign expert (Peter Boyle). In each case, Redford stepped as far away from his previous Hollywood image as possible, succeeding in winning both critical and moviegoer praise for these risky moves.

The banner year 1973 marked the beginning of Redford’s reign as Hollywood’s top audience draw with back-to-back blockbusters. “The Way We Were” reunited him with Pollack for a tear-jerking period romance between WASPy collegian Redford and a political activist (Barbra Streisand). The film yielded a massive chart hit with Streisand’s theme song, and set a new standard for Hollywood romances to follow. Redford then paired again with Hill and Newman for “The Sting,” a sparkling caper comedy about two con men who aspire to fleece a mob boss (Robert Shaw). The picture, which touched off a modest revival of the music of jazz era composer Scott Joplin, pulled in $160 million at the box office and gave Redford his sole Oscar nomination for acting.

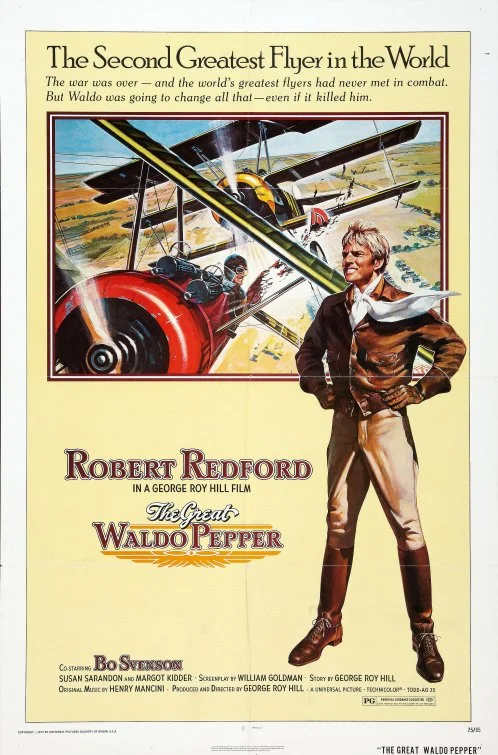

After a slight stumble as Jay Gatsby in Jack Clayton’s flawed “The Great Gatsby” (1974) and as a barnstorming trick pilot in George Roy Hill’s “The Great Waldo Pepper” (1975), Redford enjoyed a second two-fer of hits with “Three Days of the Condor” (1975) and “All the President’s Men” (1976). The former was a tense spy thriller from Sydney Pollack about a CIA operative (Redford) on the run from his own agency, while the latter was a superior political drama based on the investigation of The Washington Post reporters Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) and Bob Woodward (Redford) into the Watergate break-in, which eventually lead to the ousting of President Richard Nixon. The film earned several Academy Awards and yielded a substantial hit for Redford’s production company, Wildwood films, which helped bring the picture to the screen. After a supporting role in Richard Attenborough’s massive, all-star World War II drama “A Bridge Too Far” (1977), Redford ended the 1970s on a high note with Sydney Pollack’s “The Electric Horseman” (1979), an engaging hit about a failed rodeo champion searching for dignity.

Redford made his directorial debut in 1980 with “Ordinary People,” a gripping drama about a family struggling to come to grips with their son’s depression and guilt over the death of a sibling. Redford drew remarkable performances from his cast, especially Mary Tyler Moore as a brittle grieving mother, and earned an Oscar for Best Director. The following year, he founded The Sundance Institute, a non-profit organization built to assist aspiring filmmakers and theater artists in developing their talent. Located in Park City, UT, near where he had maintained a home since the early ’60s, Redford soon expanded the institute’s influence to the Utah/U.S. Film Festival, which was transformed into the Sundance Film Festival in 1985 and became one of the leading film events for independent filmmakers in America. Years later, a cable channel and chain of theaters – all bearing the Sundance brand – were launched in 1996 and 2005, respectively.

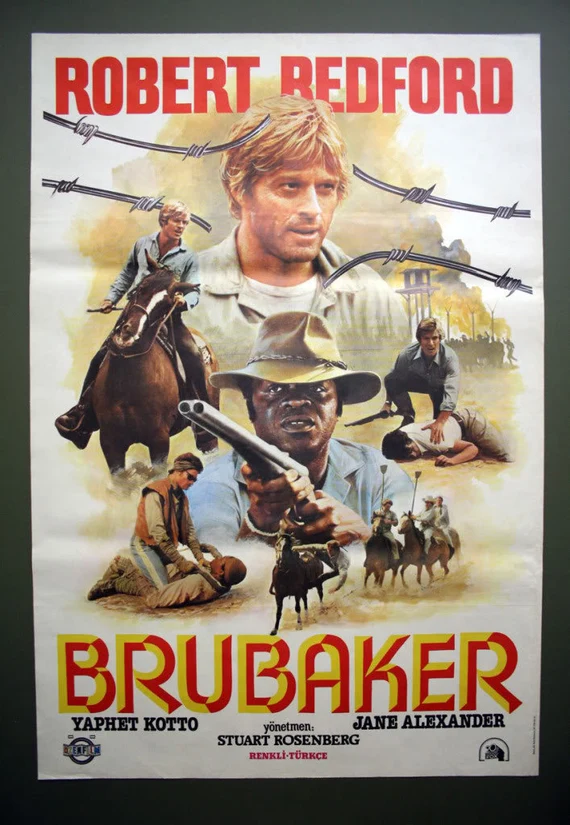

Redford continued to act throughout the 1980s, though the quality of his pictures waxed and waned throughout the decade. Hits included “Brubaker” (1980), a tough drama about a prison warden who impersonates an inmate to investigate the conditions in his own facility; Barry Levinson’s entrancing baseball fantasy “The Natural” (1984), with Redford as a former golden boy player who returns to the majors to give hope to a struggling team; and Sydney Pollack’s sweeping, Oscar-winning period romance “Out of Africa” (1985), with Redford as a big-game hunter in Africa who romances Danish author Karen Blixen (Meryl Streep). Less successful were Ivan Reitman’s comedy “Legal Eagles” (1985), which floundered at the box office and arrived on syndicated television with a completely different ending, and Redford’s sophomore directorial effort, “The Milagro Beanfield War” (1988), which earned mixed reviews and middling box office returns. Redford also divorced his wife in 1985 and courted several notable women, including his “Milagro” star Sonia Braga, before settling into a long term relationship with German artist Sibylle Szaggars in 1996.

The 1990s saw Redford balancing acting with behind-the-camera work on a regular basis, as well as maintaining his growing Sundance empire. “Havana” (1990) was a failed period drama, with Redford as an American gambler who is drawn into the Cuban revolution of 1960, while “Sneakers” (1992) was an entertaining comedy/drama with Redford as the leader of a team of rogue security operatives – including Sidney Poitier, Ben Kingsley, River Phoenix and Dan Aykroyd – who tangle with nefarious government types. “Indecent Proposal” (1993) was perhaps the most dreadful film on Redford’s CV – directed by Adrian Lyne, it was exploitation tricked out as a concept movie, with Redford as an amoral millionaire who offers a money-strapped couple (Demi Moore and Woody Harrelson) a fortune if he can sleep with the wife for one night. “Up Close and Personal” (1996) was a glossy and fictionalized take on the life of news reporter Jessica Savitch with a script by Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne. The former film made a mint; the latter film was memorable only for spawning the Celine Dion soundtrack single, “Because I loved You” – certainly not for any chemistry or lack thereof between the veteran Redford and the much younger Michelle Pfeiffer.

Redford’s efforts as director and producer during this period were more rewarding to audiences and to his own career. Redford directed, produced, and narrated, “A River Runs Through It” (1992) a moving period drama about two young men (Brad Pitt and Craig Sheffer) coming of age during the first World War and Great Depression. Exceptionally well performed by its cast, it earned an Oscar for Best Cinematography, as well as a director nomination for Redford. He followed this with “Quiz Show” (1994), a fascinating drama about the participants in the infamous cheating scandal that rocked the TV game show boom of the 1950s. Though the film struggled to find a substantial audience, it was lauded for its dramatic quality and received four Oscar nominations, including Best Director for Redford and Best Adapted screenplay for Paul Attanasio. And 1998’s “The Horse Whisperer” marked the first time Redford directed, produced and starred in the same picture. The film, about a horse trainer (Redford) who helps a young rider (Scarlett Johansson) recover from a traumatic injury, received mixed reviews but scored major ticket sales. Redford also served as producer for numerous independent features during the 1990s, including Michael Apted’s documentary “Incident at Oglala” (1992), which he also narrated; Edward Burns’ “She’s the One” (1996); the HBO Native American series “Grand Avenue” (1996); and “Slums of Beverly Hills” (1998). The ’90s also saw him bring home a flurry of awards, including the Cecil B. DeMille Award in 1994 and the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Screen Actors Guild in 1996.

Redford’s next directorial effort, “The Legend of Bagger Vance” (2000), starred Will Smith as a mystical golf caddy who aides a struggling duffer (Matt Damon) to recover his game and his self-confidence. The film performed well at the box office, due mainly to its two leads’ star appeal, but received middling reviews. Redford himself made sporadic film appearances in Tony Scott’s action hit “Spy Game” (2001) and “The Last Castle” (2001) – the latter of which tanked despite the presence of James Gandolfini and Mark Ruffalo. More successful was “The Motorcycle Diaries” (2004), which Redford produced, as well as several TV-movie adaptations of Tony Hillerman’s Native American mysteries – including “Skinwalkers” (2002), “Coyote Waits” (2003), and “A Thief of Time” (2004), which aired on PBS. For his numerous contributions to independent cinema, Redford was given an honorary Oscar in 2002. In 2005, Redford was honored alongside Tony Bennett, actress Julie Harris, and Tina Turner by the Kennedy Center.

Redford’s turns as a leading man continued into the 21st century, though they became harder to find. The well-received thriller “The Clearing” (2004) barely saw a theatrical release, and while Lasse Hallstrom’s “An Unfinished Life” gave Redford a plum role as a cantankerous rancher who is forced to reconcile with his daughter-in-law (Jennifer Lopez), the film vanished at the box office due to the restructuring of its distributor, Miramax. He later lent his gravelly tones to the horse Ike in the live-action/CGI remake of “Charlotte’s Web” (2006) and returned to directing with the politically-charged drama “Lions for Lambs” (2007), co-starring Meryl Streep and Tom Cruise (who also produced under his new shingle at United Artists). The picture opened to moderate business and less-than-enthusiastic reviews. Redford worked both sides of the camera in the sociopolitical drama “The Company You Keep” (2013), directing a script by Lem Dobbs (“The Limey”) and starring as a former member of a 1960s radical group in hiding whose new identity is threatened with exposure by a young investigative journalist (Shia LeBeouf). He followed that with the claustrophobic “All Is Lost” (2013), in which he played an unnamed man whose solo ocean voyage becomes a fight for survival.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

Robert Redford, who has died aged 89, was the golden boy of American cinema for more than 50 years.

In one respect, with his blond good looks, he conformed to a mythic Californian stereotype, or what Dustin Hoffman called a “walking surfboard”. However, Redford managed to expand as much as he could within his limitations, once claiming: “I’m interested in playing someone who bats in 10 different ways.”

Redford, who was always ill at ease about his looks, was described by Sydney Pollack, for whom the actor made seven films (including the spy thriller Three Days of the Condor in 1975), as “an interesting metaphor for America, a golden boy with a darkness in him”. To many of his characterisations, he added a wry wit, able to hint, via subtle nuance, at a more complex psychology hidden beneath the surface.

Romantically flawed and fallen heroes were his forte, so he was perfectly cast in the title role of The Great Gatsby (1974). “I wanted Gatsby badly,” he commented. “He is not fleshed out in the book and the implied parts are fascinating.”

According to F Scott Fitzgerald’s description of the novel’s hero, “Jay Gatsby had one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced, or seemed to face, the whole external world for an instant and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favour … he invented just the sort of Jay Gatsby that a 17-year-old boy would be likely to invent, and to this conception he was faithful to the end.” Redford, like Gatsby, carefully polished his image of an alluring, dispassionate, handsome icon

Charles Robert Redford Jr was born in Santa Monica, California, the son of an accountant with Standard Oil, and his wife, Martha (nee Hart). The family moved to Van Nuys, California, where Robert went to Van Nuys high school. He was blessed early on with a graceful athleticism, excelling in swimming, tennis, football and baseball, the last of which won him a scholarship to the University of Colorado, where he could also indulge his love for climbing and skiing.

But he soon became frustrated by what he called “test-tube athletes”. As the character of the Olympic skier that he played in Downhill Racer (1969) says: ‘“I never knew what it was like to just enjoy a sport. I was always out there grovelling to win. You begin to fear not winning.”

When his lack of attendance at baseball practice led to him losing his scholarship, he left for Europe in 1957. Because he had displayed a certain talent as a caricaturist in high school, he did what all hopeful American artists did: he went to paint in Paris before being forced into the realisation that, as an artist, he was mediocre. On his return to the US, he married his girlfriend, Lola Van Wagenen, in 1958 and studied scenic design at the Pratt Institute in New York

None the less, in 1959, he made his professional stage debut on Broadway with a small role as a basketball player in Tall Story, which he repeated uncredited in the feature film version starring Jane Fonda the following year. During the try-out run for The Highest Tree (1959), a short-lived play about a nuclear scientist, his first child, Scott, died of sudden infant death syndrome.

He made it big on Broadway in Norman Krasna’s Sunday in New York (1961) and even bigger in Neil Simon’s hit comedy Barefoot in the Park (1963), which he reprised in the screen version opposite Fonda in 1967. He remained in the play for the first year of its four-year run, but never worked in the theatre again.

At the same time, he was racking up numerous TV credits, including the callow Don Parritt in Sidney Lumet’s production of Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh (1960) and a memorable appearance as the Angel of Death in an exceptional 1962 Twilight Zone episode called Nothing in the Dark

Redford’s first credited film role was in the untrumpeted War Hunt (1962), an off-beat little picture, shot in 15 days, in which Pollack also made his screen debut as a performer. They played members of a platoon in Korea, one of whom (John Saxon) is schizophrenic. He goes out on lone missions and kills the enemy with a stiletto. Redford’s character tries to rescue an orphan from Saxon’s influence.

It was three years before he returned to the big screen, gaining some attention in Robert Mulligan’s Inside Daisy Clover (1965), in which he played Natalie Wood’s egotistical, bisexual matinee idol husband and for which he won the Golden Globe award for most promising newcomer.

This promise was fulfilled in his following films, including Arthur Penn’s steamy The Chase (1966), in which Redford played an escaped convict whom the fair-minded sheriff (Marlon Brando) tries to protect from being lynched by the inhabitants of a small Texas town. Although the role required Redford to spend much of the film running through rice fields, he opted for that rather than playing the sheriff, the part he was offered originally.

He seemed incredibly relaxed and confident in the early stages of his career, rejecting two roles offered to him by Mike Nichols – the younger man in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (eventually played by George Segal), and Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate, because he felt too old for the part, even though he and Hoffman, who made his name from the part, were almost the same age. He also turned down the John Cassavetes role in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby.

Instead, he preferred to co-star with Wood again in Pollack’s This Property Is Condemned (1966), based on a Tennessee Williams play, as a mysterious railway official. Next came Barefoot in the Park, and then one of his best-known roles, Sundance – a role passed over by Brando, Warren Beatty and Steve McQueen – opposite Paul Newman’s Butch Cassidy in one of the most successful westerns ever

George Roy Hill’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) created at its core an irresistible chemistry between its two male leads as charming outlaws, leading to a string of buddy movies, including the equally successful The Sting (1973) with the same director and stars, this time playing scam artists in 1930s Chicago.

Between the two hit movies, Redford made several films, the best being Michael Ritchie’s satirical The Candidate (1972), about a presidential campaign, in which he was well cast in the vapid title role, and Pollack’s The Way We Were (1973). The latter, an odd couple romantic comedy with Redford as an upper-crust Wasp who does not take politics seriously, and Barbra Streisand as a working-class Jewish leftist uncompromising in her political beliefs, saw them both performing well within their comfort zones.

By the end of the 60s, Redford had become one of the world’s top film stars and box-office attractions, with carefully chosen projects to keep alive his screen persona in glossy Hollywood star vehicles. Among the exceptions were movies that satisfied his liberal leanings, especially Alan Pakula’s Watergate exposé, All the President’s Men (1976).

The perspicacious Redford had bought an option on the book by the Washington Post journalists Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward prior to its publication in 1974 for $450,000. William Goldman, who had written three buddy movies in a row for Redford – Butch Cassidy, The Hot Rock (with Segal, 1972) and The Great Waldo Pepper (with Bo Svenson, 1975) – was hired to supply another one for the star and Hoffman, delivering a sort of “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid Bring Down the Government”, as one Washington Post wit described

In the All the President’s Men, of the two leads, Redford had the edge, managing to combine a dry humour, a convincing intelligence and a determined idealism. According to Hoffman, the reason the film was a top earner was because “it is what the public always wanted: that beautiful Wasp finally wound up with a nice Jewish boy”.

In the 80s, Redford gradually scaled down his acting, appearing in only four films, having taken up producing and directing. At the same time, he established the Sundance Institute on his 7,000-acre estate in Provo, Utah, providing workshops, development resources and support to promising independent film-makers.

In 1978, Redford co-founded the Sundance film festival,held in Park City and Salt Lake City, Utah every January as a shop window for independent cinema, and remained a godfather to it. A passionate environmentalist, he also co-founded the Institute for Resource Management, a forum to encourage land developers and environmentalists to work together.

In later acting assignments, he was shown in a noble, almost saintly, light, consistently backlit to turn his golden hair into a saintly halo: as a prison reformer in Brubaker (1980), a mythical baseball player in The Natural (1984), and the English big game hunter Denys Finch Hatton (though there was no attempt to get Finch Hatton (though there was no attempt to get the accent),the lover of Karen Blixen (Meryl Streep) in Out of Africa (1985).

Redford’s first film as a director, Ordinary People (1980), was a middle-class family drama, elegantly shot though not very original, with a sentimental father-son solution. Nevertheless, the film won Oscars for best picture and best director – Redford went on to win an honorary Oscar, too, in 2002 – as well as best supporting actor, for Timothy Hutton, and best adapted screenplay. Its success encouraged Redford to continue directing over the next decades.

The Milagro Beanfield War (1988) was a homespun fable of a New Mexican farmer deflecting water from a housing development to start his own beanfield. A River Runs Through It (1992), shot in Montana (Philippe Rousselot won an Oscar for his cinematography), used fly-fishing as a metaphor for life in an understated way; and Quiz Show (1994) was a gripping account of a television scandal in 50s America, when a winning contestant of a popular programme was exposed as a fraud.

Redford directed himself for the first time in The Horse Whisperer (1998), as a Montana cowboy who cures traumatised horses, a role that fitted him as snugly as his faded denims. The Legend of Bagger Vance (2000), continued his almost mystic interest in sport with a nostalgic look at golf between the wars, while Lions for Lambs (2007) was a flabbily liberal and verbose response to the Iraq war.

He starred in and directed The Company You Keep (2012), a well-intentioned political drama on the Weather Underground 30 years after their terrorist activities. Yet, though one would be hard put to call Redford an auteur, there is no denying that his choice of films reflected his political views and his passion for the American west.

From the 90s, the reasons for some of his acting choices were a trifle less clear. In Adrian Lyne’s Indecent Proposal (1993), Redford’s character, admitting to advanced middle-age, offers to pay $1m to sleep with Demi Moore, with her husband’s approval. He finally gave in to advancing years at the age of 68 and played a crusty and grizzled rancher in Lasse Hallstrom’s An Unfinished Life (2005), the sort of role Newman and Clint Eastwood had been playing for years.

Never straying too far from his persona of dignified masculinity, Redford continued to be active into his 80s. His solo performance in All Is Lost (2013) as a castaway seaman trying to survive was a tour de force, while he demonstrated his fitness in A Walk in the Woods (2015), and his integrity as the TV anchor Don Rather in Truth (2015). His last substantial role was as the real-life bank robber Forrest Tucker in the comedy drama The Old Man & the Gun (2018).

He is survived by his second wife, Sibylle Szaggars, an artist, whom he married in 2009 after a long relationship, and two children, Shauna and Amy, from his first marriage, which ended in divorce in 1985; their son James died in 2020.

Robert Redford, actor, producer and director, born 18 August 1936; died 16 September 2025

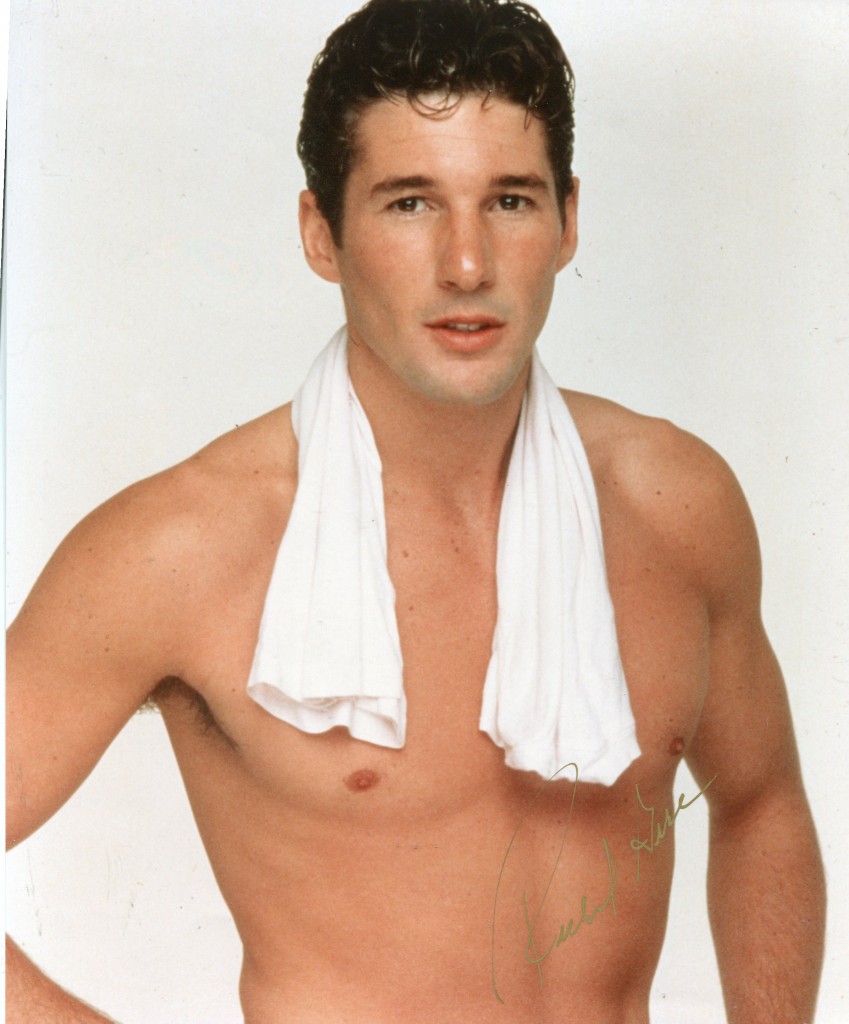

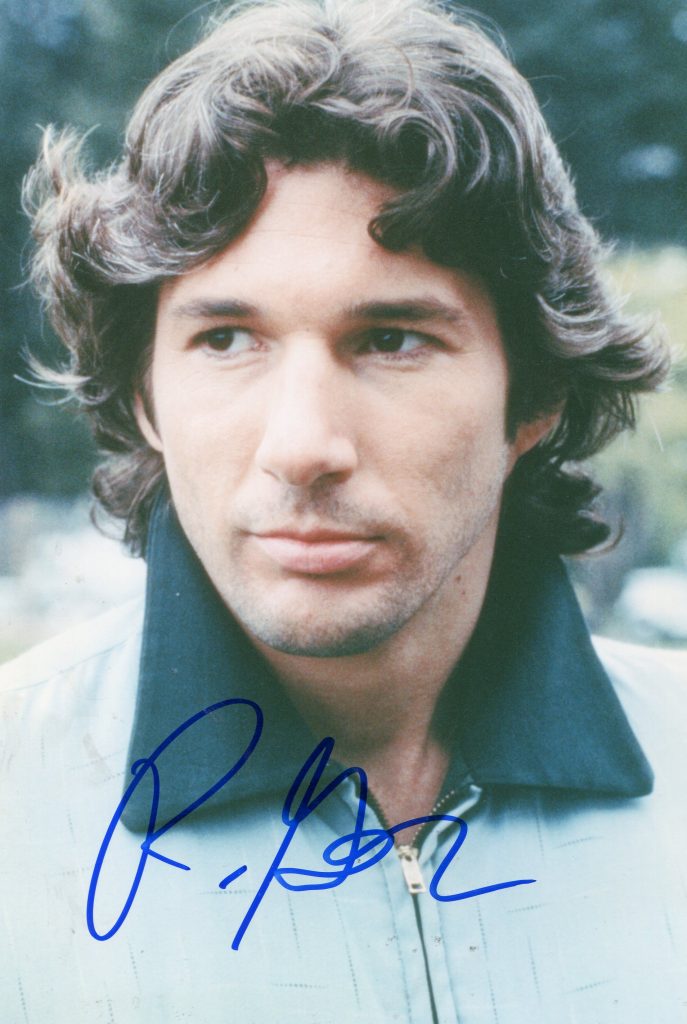

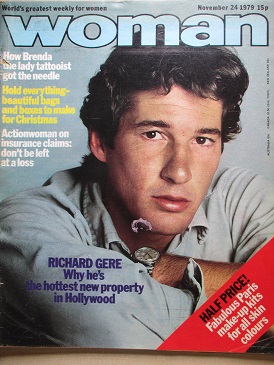

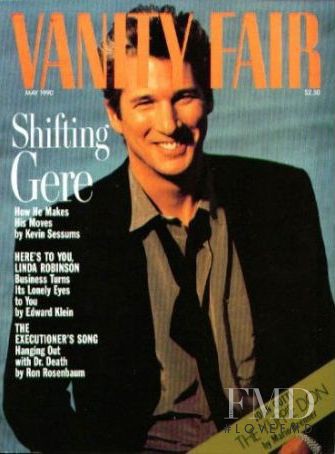

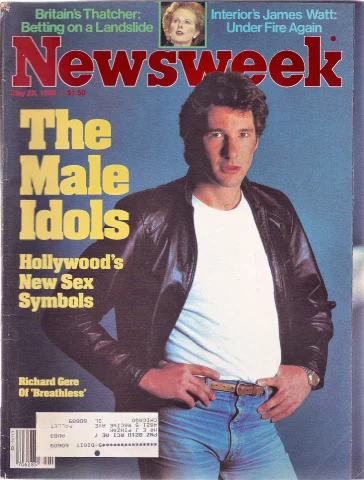

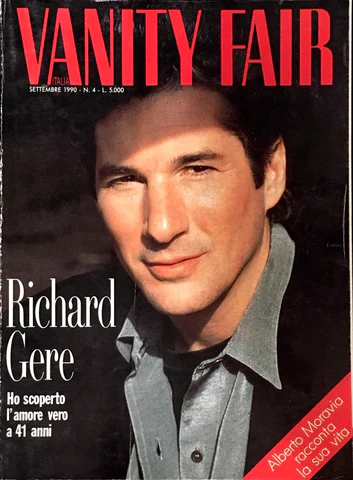

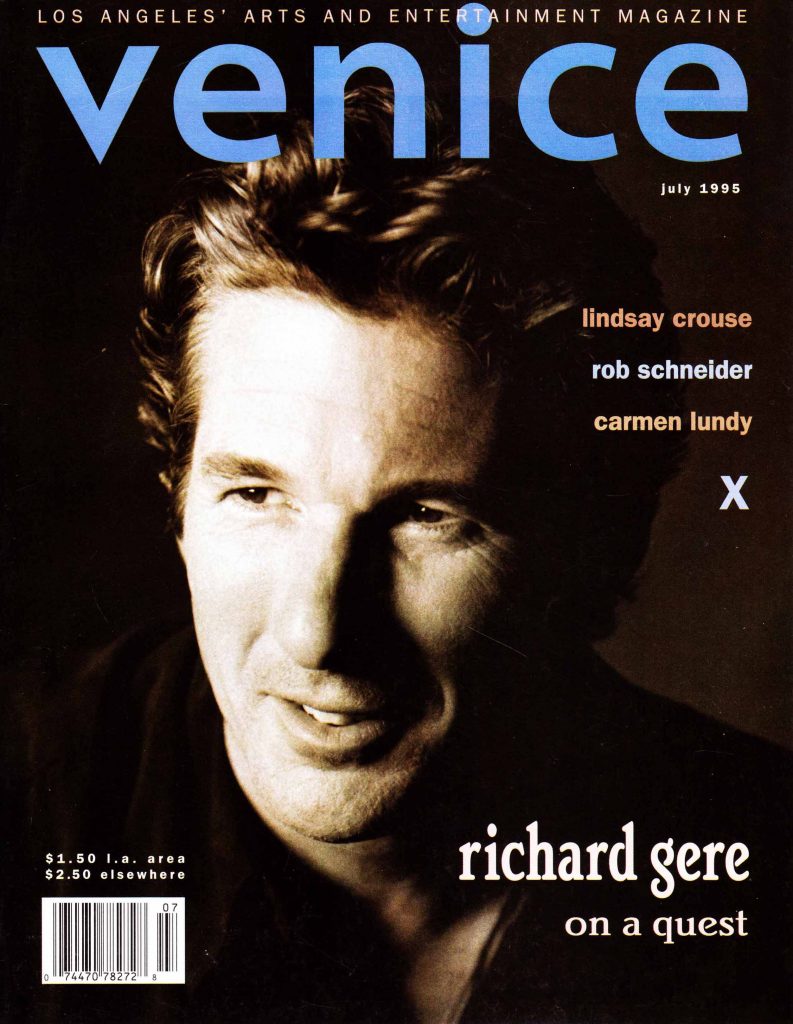

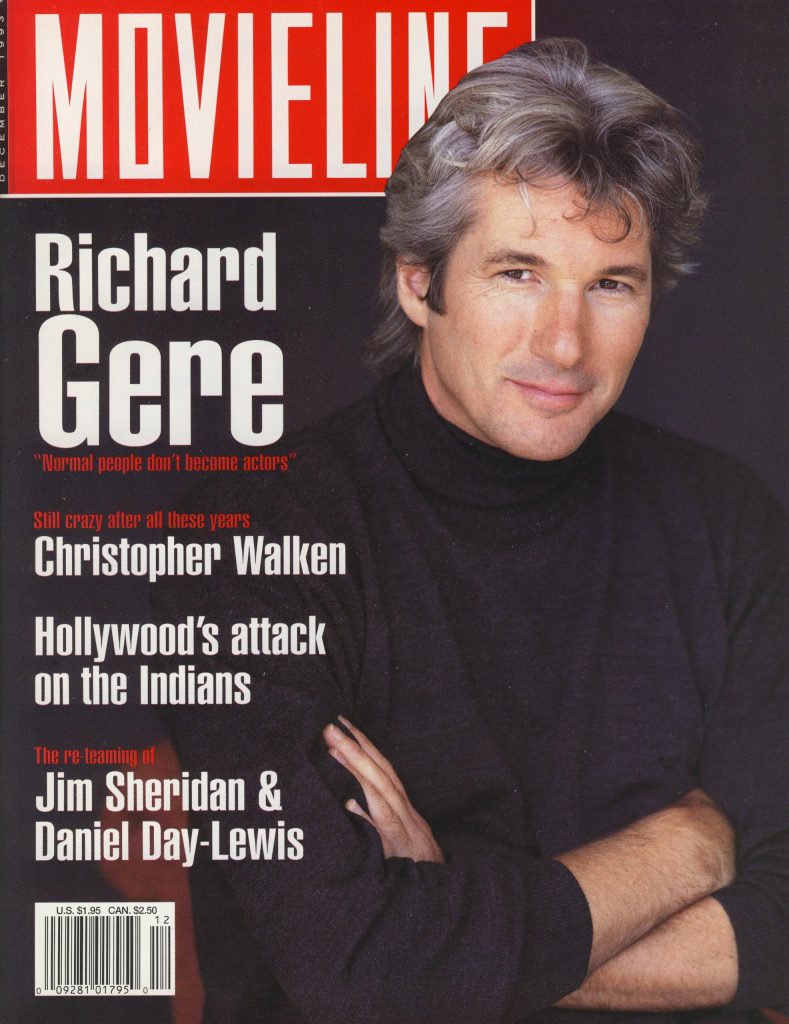

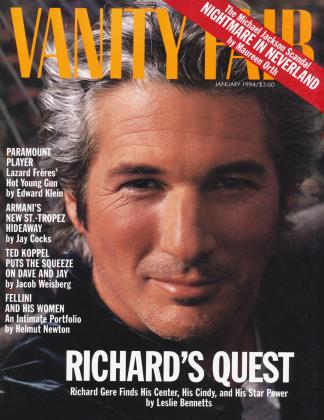

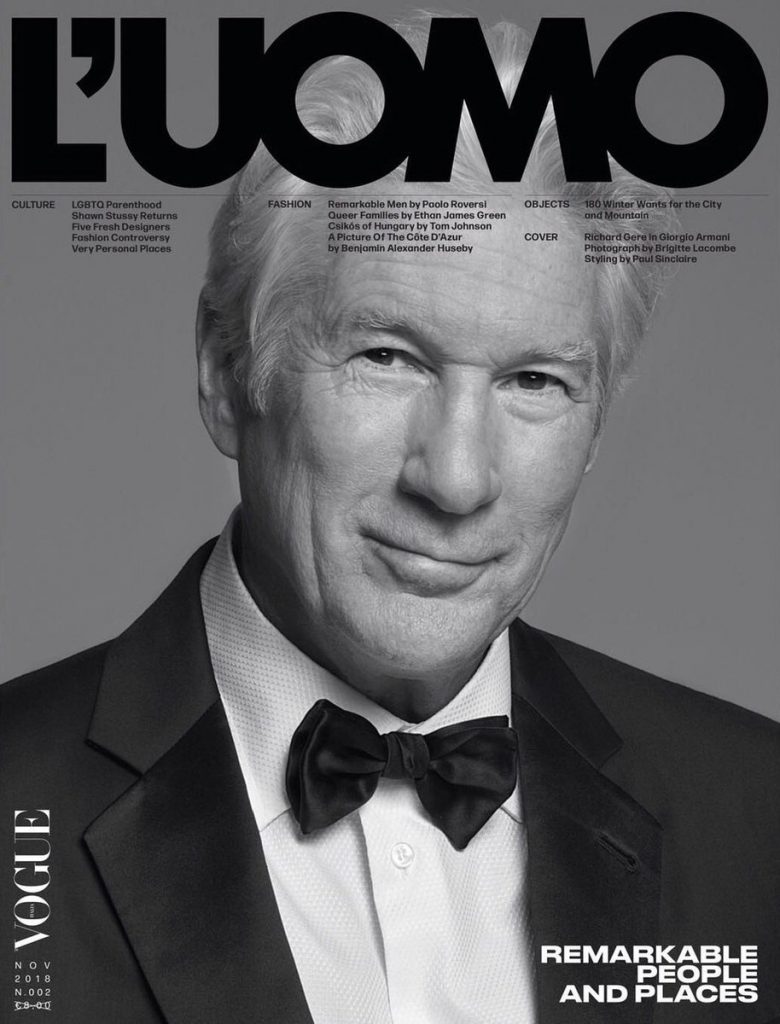

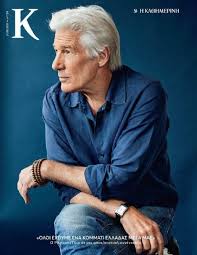

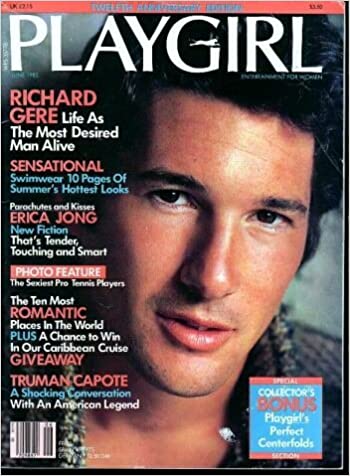

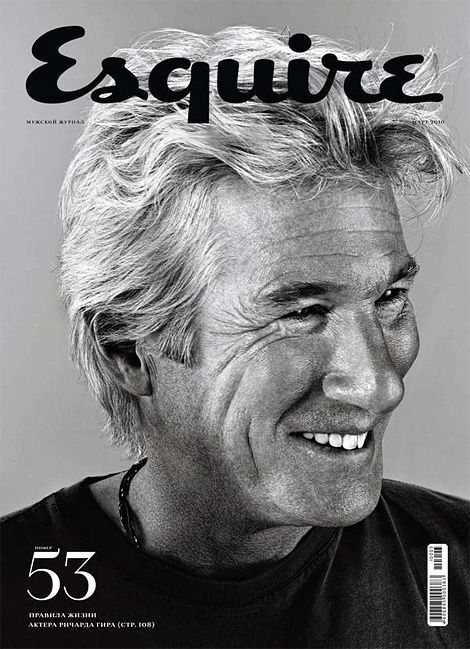

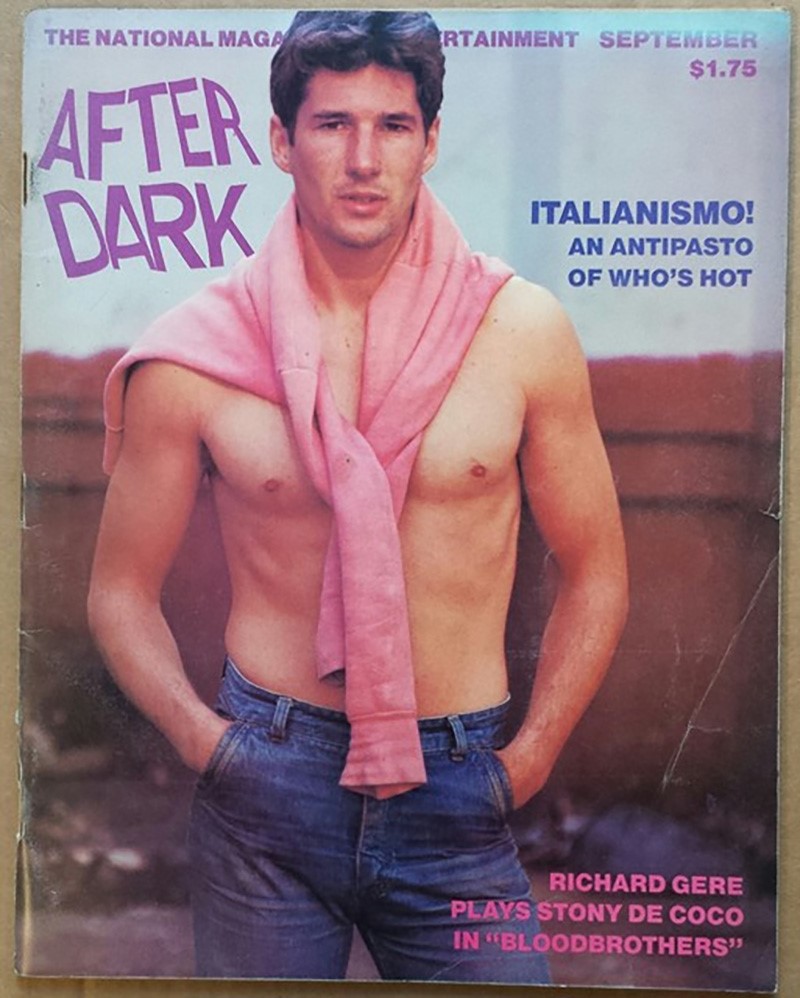

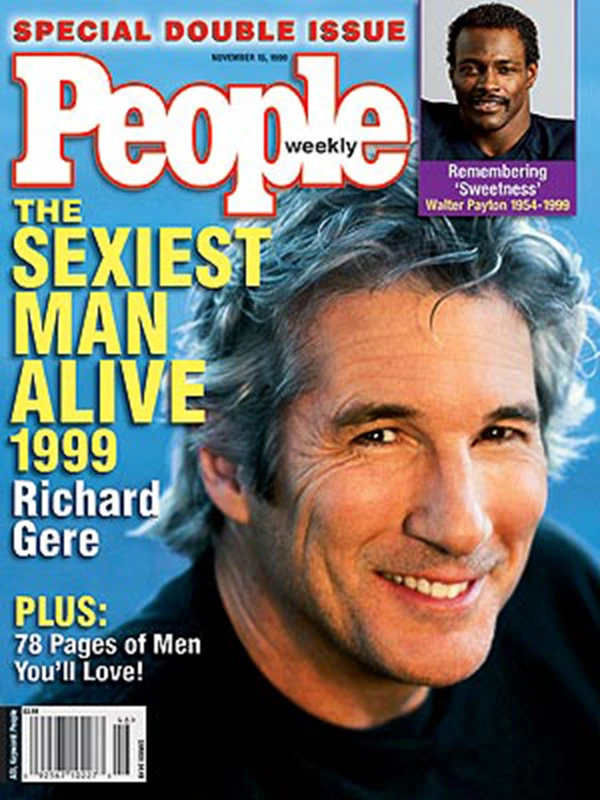

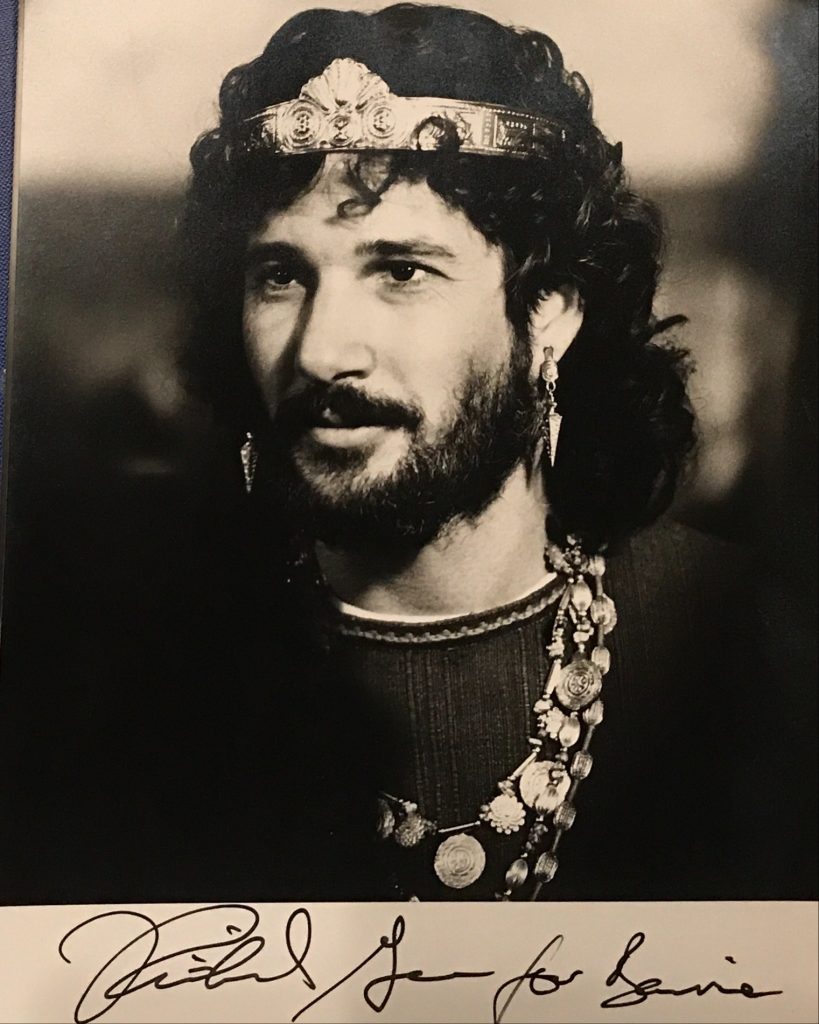

Good looks have never hindered a film star but they can make him suspect – as in the case say of Robert Taylor, who certainly did not owe his steller position to any thesping ability. Those MGM executives ho moulded Taylor’s career remembered the mesmerizing effect of Valentino and showcased Taylor so he could bring in the sort of money to satisfy stockholders. Gere has had no studio to help him. He could not have achieved his position in an age of ‘uglies’ if he had only looks: his interviews indicate a man with a almost desperate regard to be taken seriously. He is handicapped that like Valentino – with whom he shares both a self-absorption and sexual insolence – he is disregarded by men whitle their womenfolk adore him. There are worse things.” – David Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars – The Independent Years”. (1991).

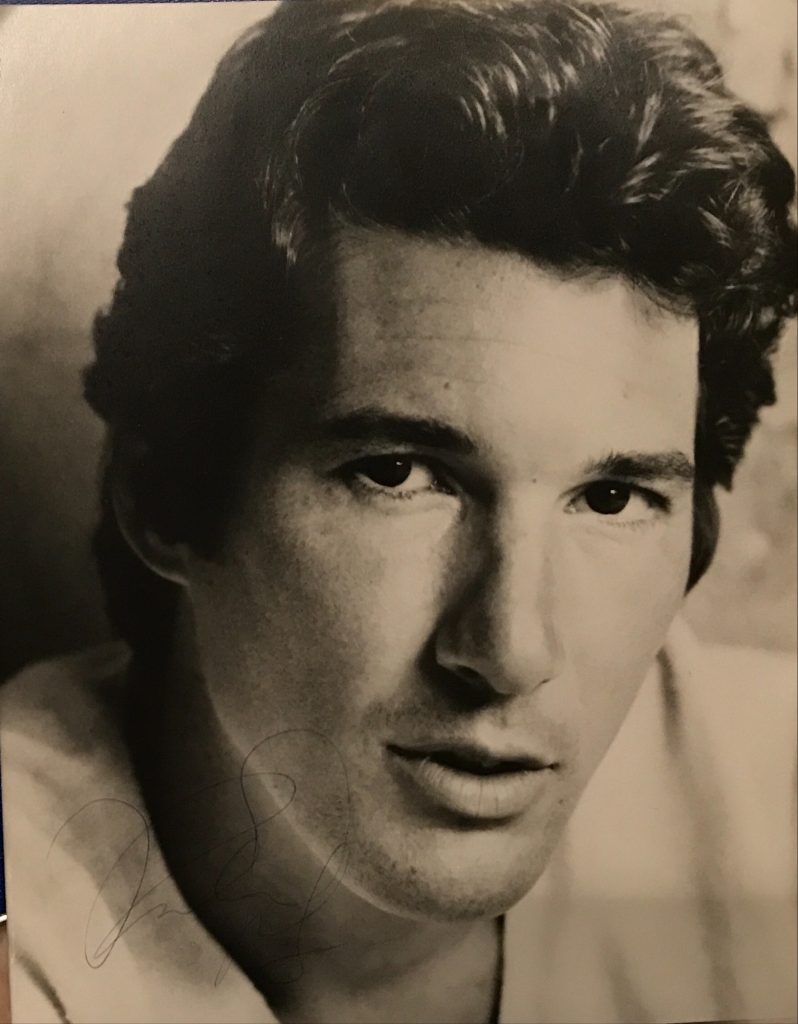

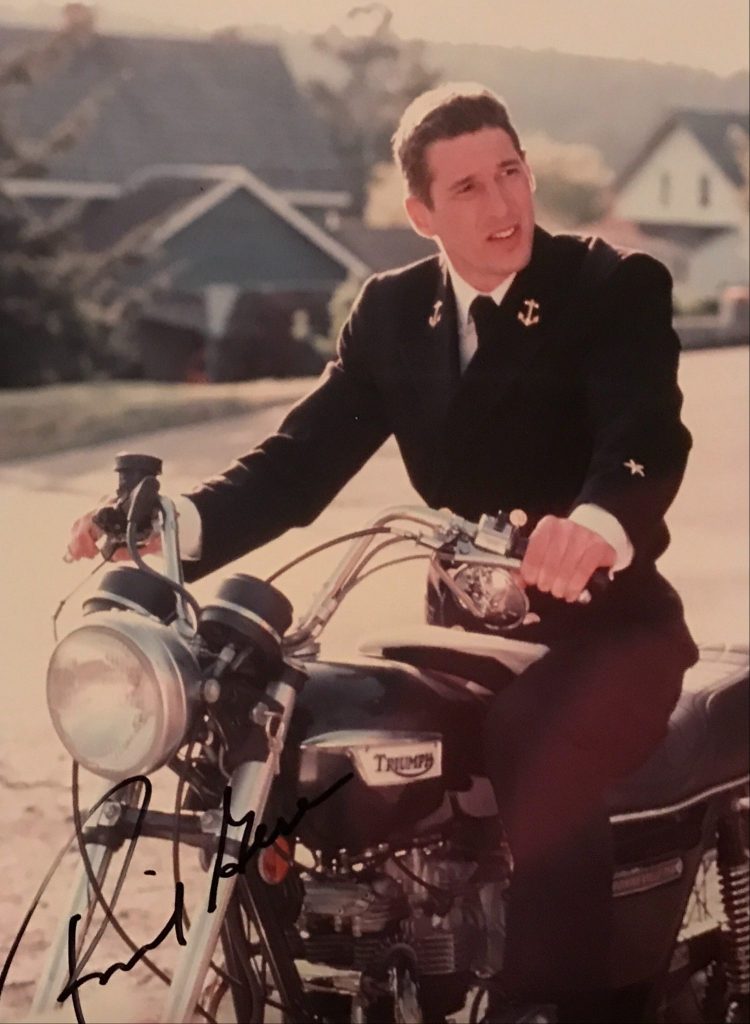

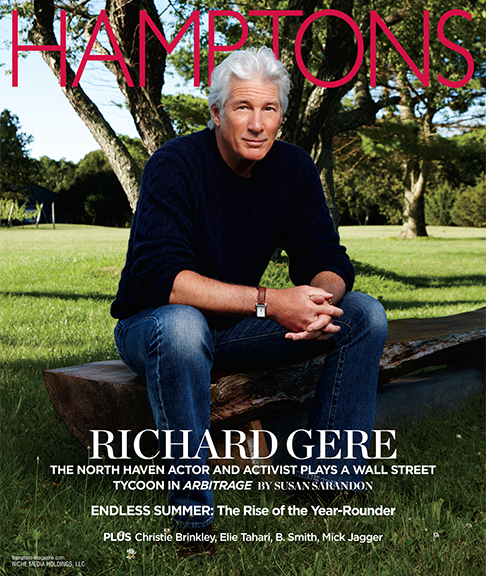

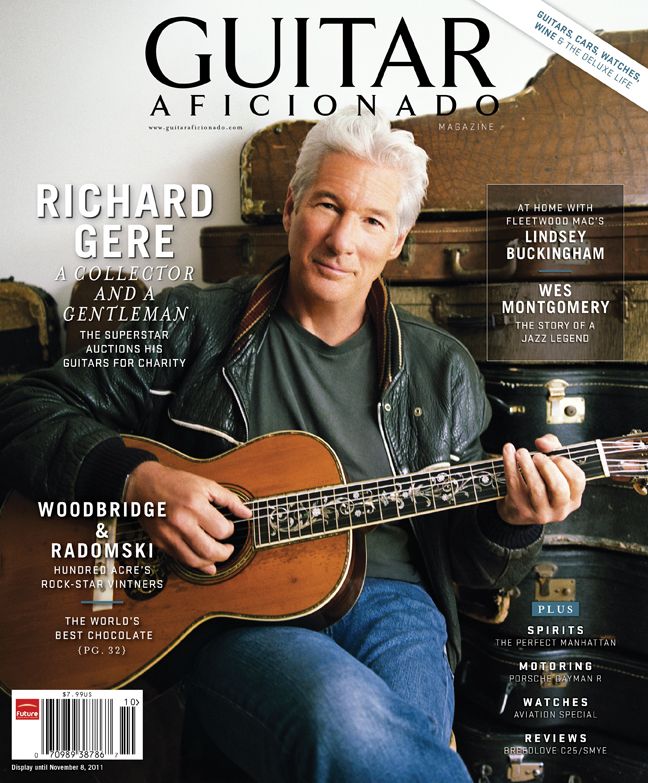

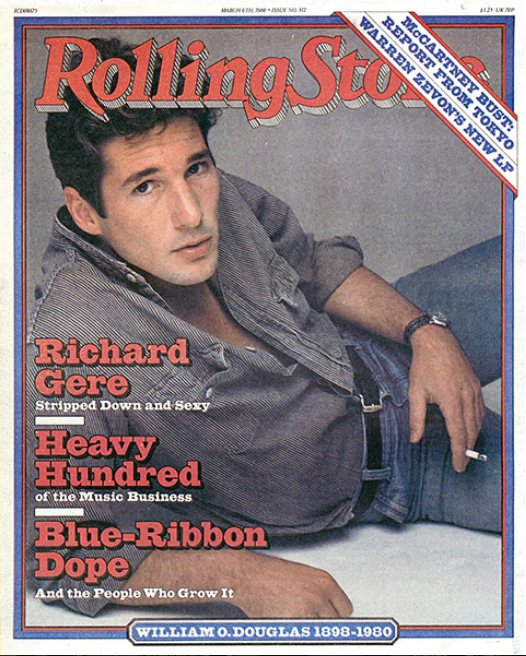

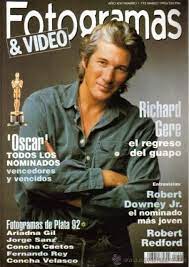

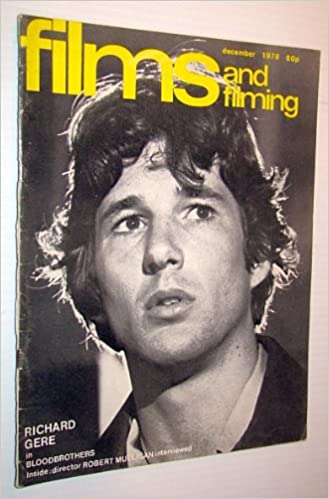

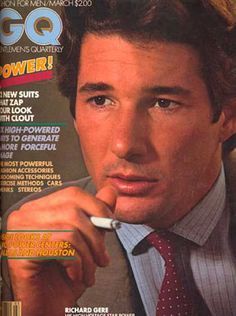

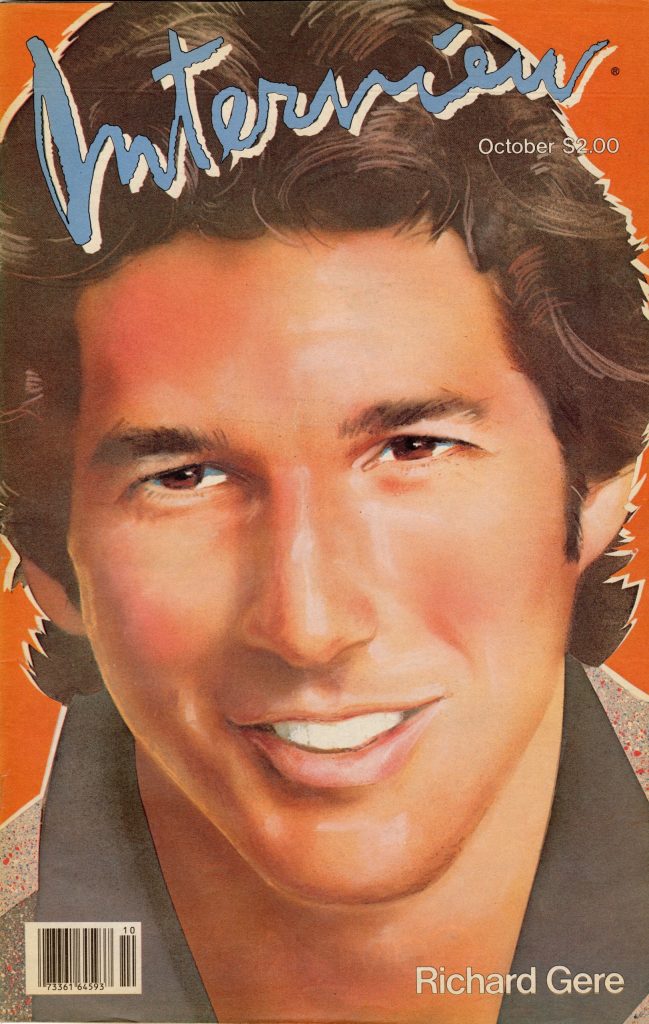

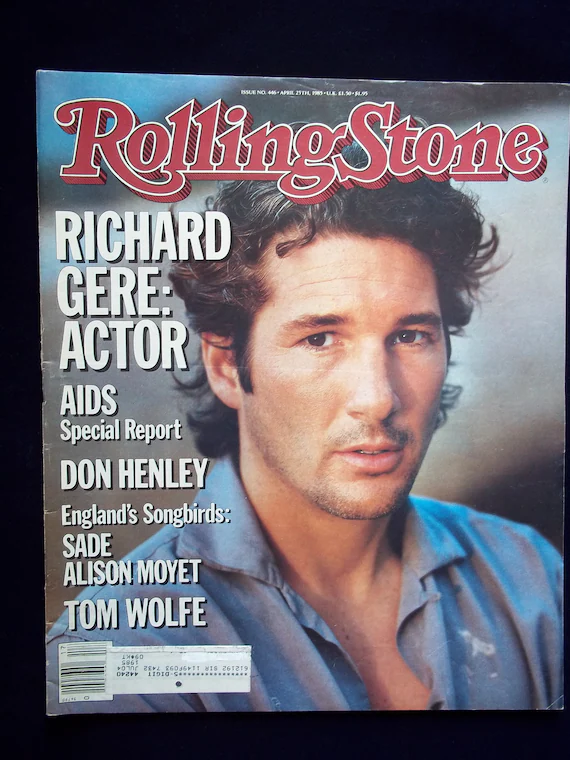

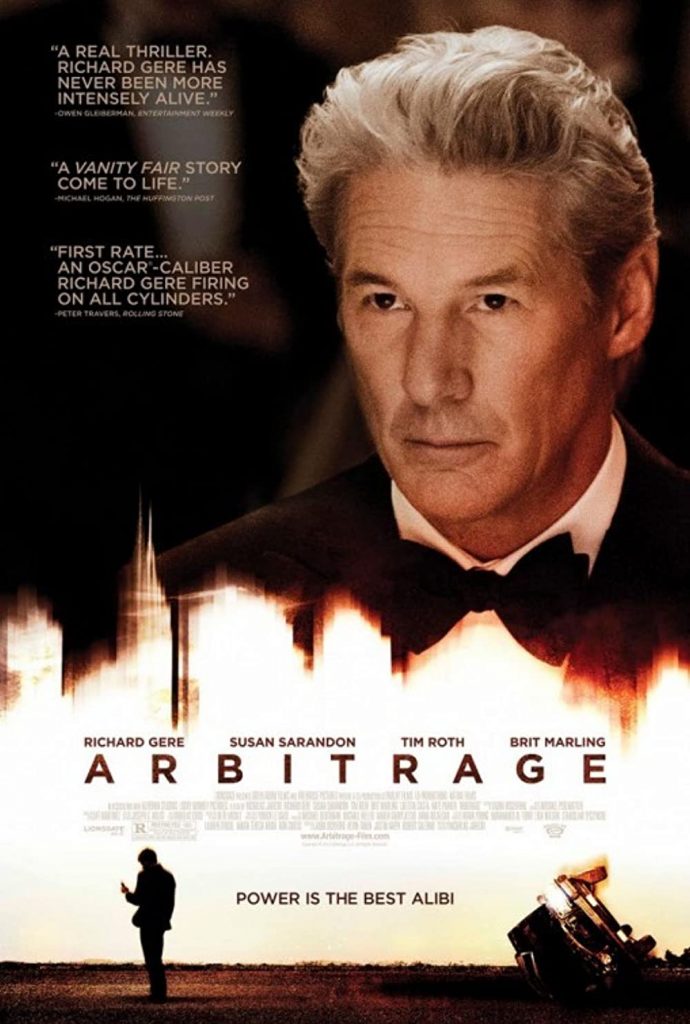

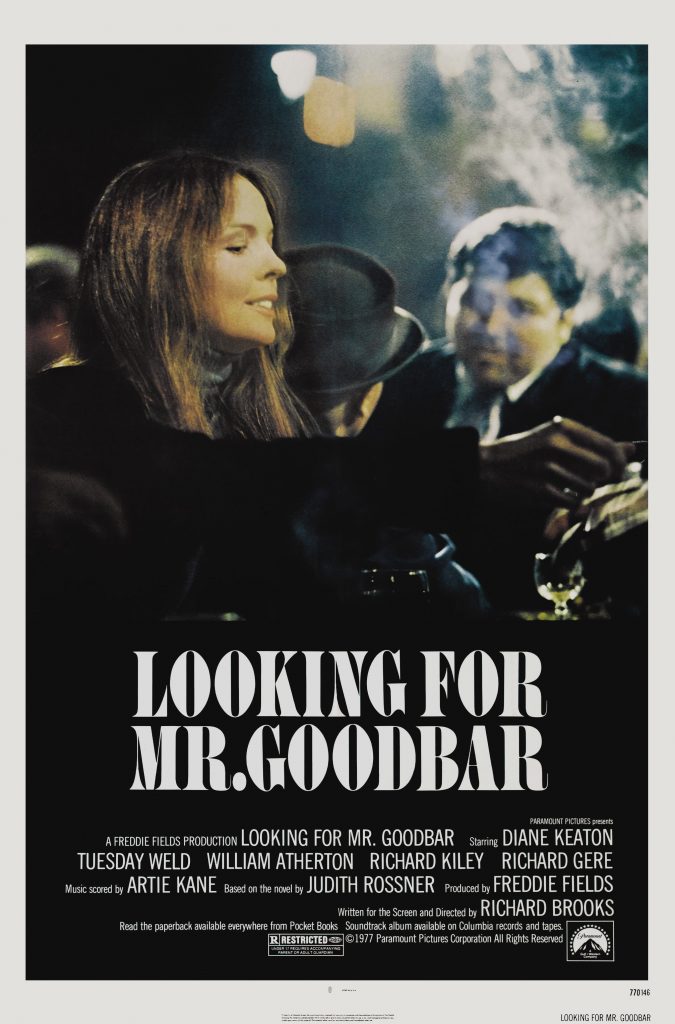

Richard Gere (born August 31, 1949) is an American actor. He began acting in the 1970s, playing a supporting role in Looking for Mr. Goodbar, and a starring role in Days of Heaven. He came to prominence in 1980 for his role in the film American Gigolo, which established him as a leading man and a sex symbol. He went on to star in several hit films including An Officer and a Gentleman, Pretty Woman, Primal Fear, and Chicago, for which he won a Golden Globe Award as Best Actor, as well as a Screen Actors Guild Award as part of the Best Cast. He is currently winning rave reviews for his performance in “Arbitrage”.

TCM overview:

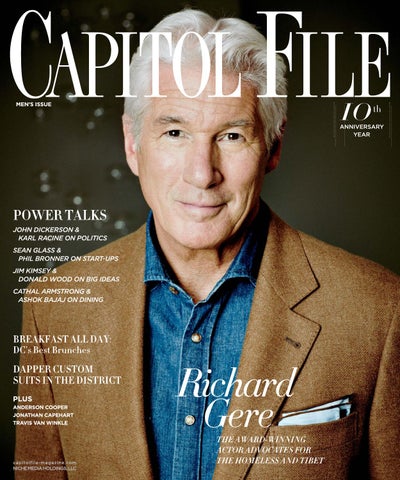

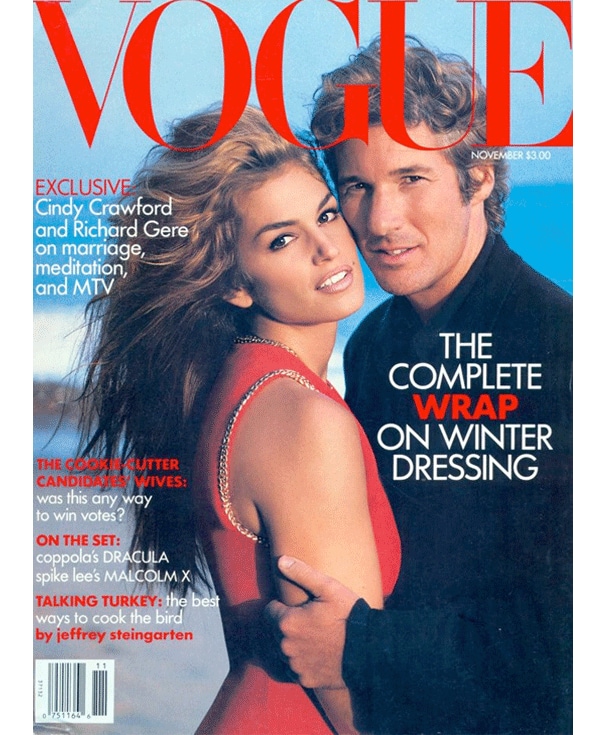

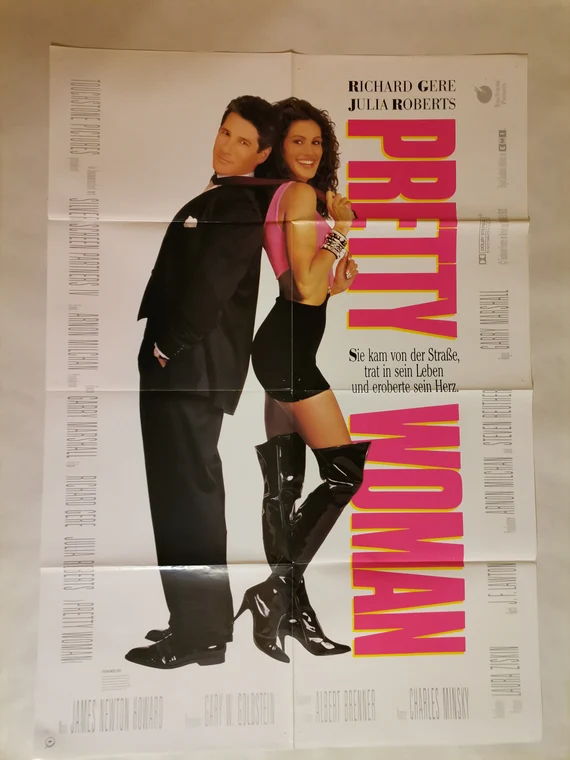

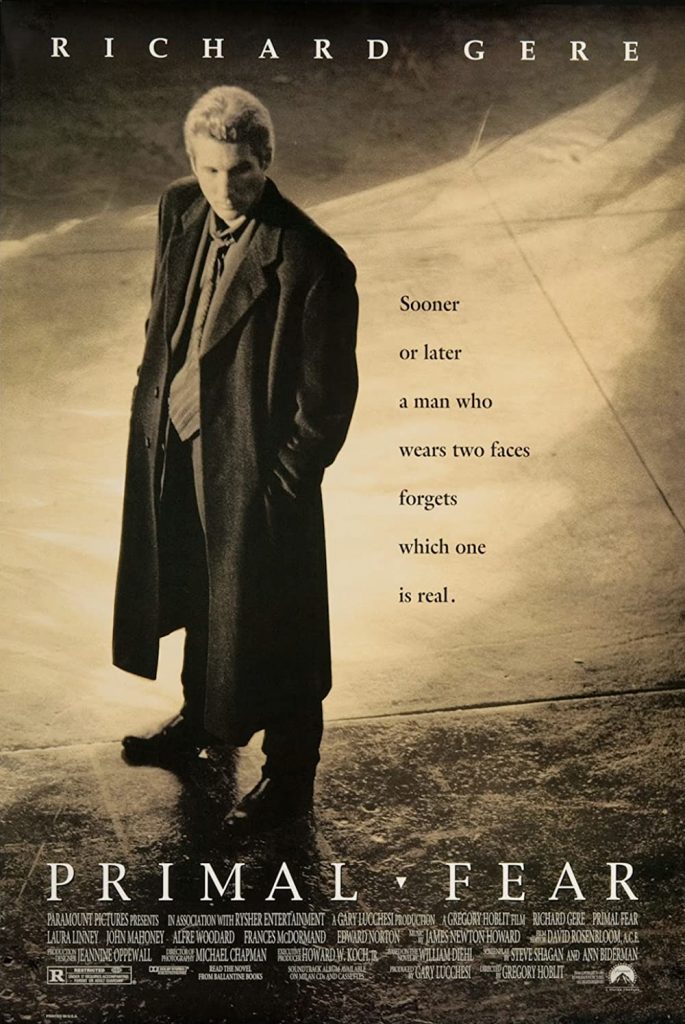

Long recognized as one of Hollywood’s most bankable leading men, actor Richard Gere was at times almost as widely known for his brief marriage to supermodel Cindy Crawford, as well as his spiritual convictions to Buddhism and political support of the region of Tibet. Emerging as an up-and-coming talent both on and off-Broadway, Gere soon garnered attention for roles in films like “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” (1977) and Terence Malick’s “Days of Heaven” (1978). A career-making turn as the titular “American Gigolo” (1980) made him an instant sex symbol, while his magnetic performance as “An Officer and a Gentleman” (1982) solidified his reputation as a top leading man. However, a series of box office disappointments followed, until his turn as a modern day Prince Charming opposite Julia Roberts in “Pretty Woman” (1990) once again made the actor a hot commodity. While offerings like the legal thriller “Primal Fear” (1996) met with modest success, Gere returned to his Broadway musical roots to reinvent himself onscreen for the Academy Award-winning film adaptation of “Chicago” (2002), which earned him a Golden Globe. Although he continued to work steadily over the following decade, it wasn’t until the harrowing drama “Arbitrage” (2012) that Gere once again found himself on the receiving end of unanimous critical praise. Over a career that experienced its fair share of highs and lows, Gere remained a consistent film presence, frequently surprising audiences with new levels of craft and charm.

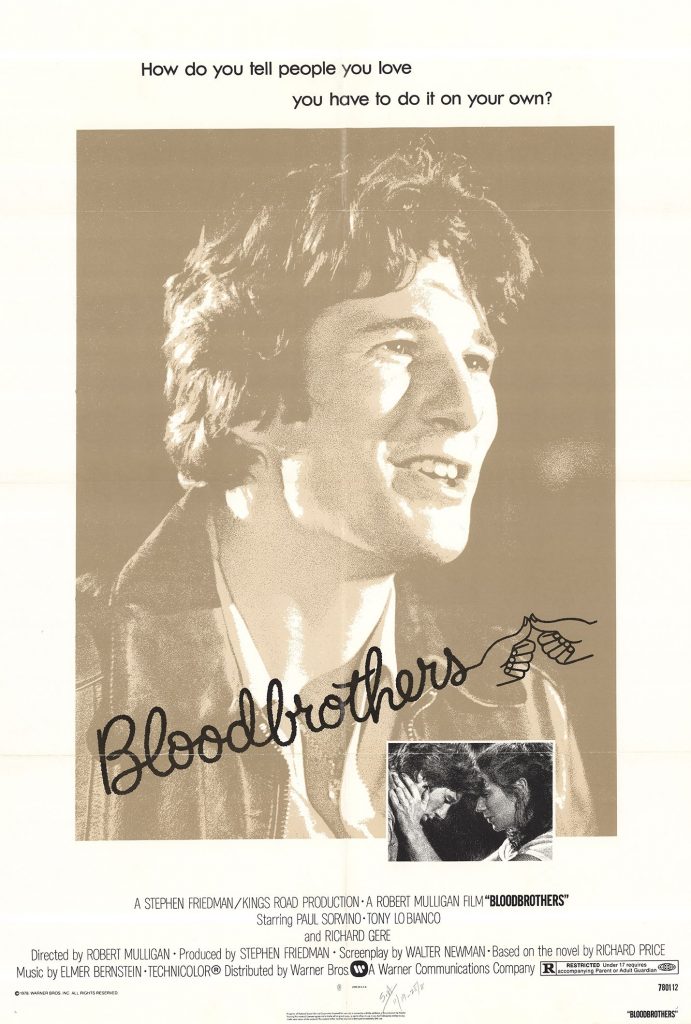

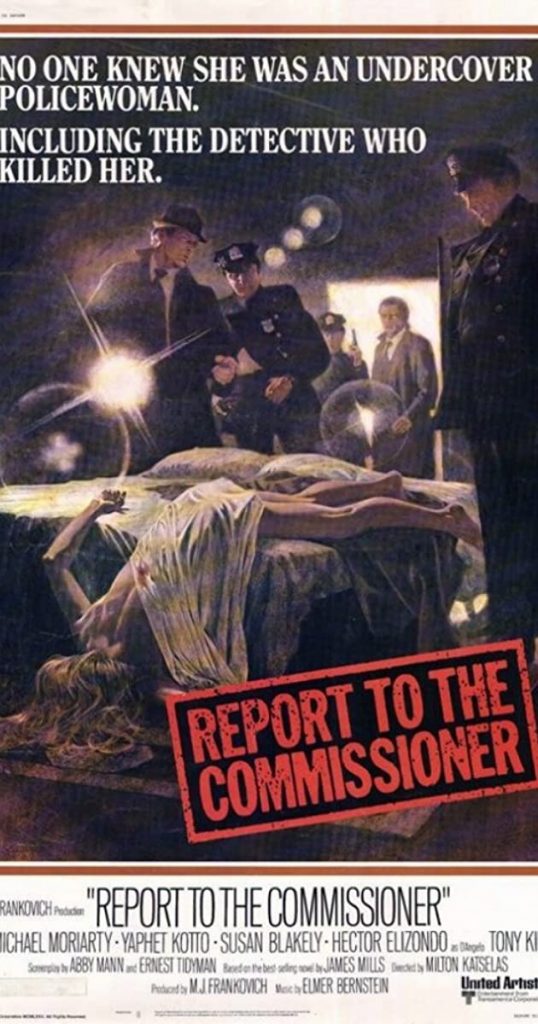

Gere was born on Aug. 31, 1949 in Philadelphia, PA, but grew up in upstate New York where his father, Homer, sold insurance and his mother, Doris, worked as a homemaker. Finding his way to the University of Massachusetts on a gymnastics scholarship, Gere studied philosophy and drama, only to drop out after two years to pursue acting. Gere spent a season each with the Provincetown Playhouse and Seattle Repertory Company before settling in NYC, where he eventually starred on Broadway as Danny Zuko in “Grease” (1973). He continued to work in theater while securing his first film parts, making his debut in “Report to the Commissioner” (1975), before finally gaining notice as Diane Keaton’s hustler beau in “Looking for Mr. Goodbar” (1977). He landed his first leads in two films released a week apart in the fall of 1978: Terrence Malick’s lyrical “Days of Heaven” and Robert Mulligan’s urban working class family drama “Bloodbrothers.” Stardom came two years later with “American Gigolo” (1980), Paul Schrader’s ambitious updating of Robert Bresson’s film “Pickpocket” (1959) to a contemporary Californian milieu. Playing a cocky prostitute, decked out in Armani suits and driving a fancy car, Gere’s character became not only a fashion statement but a symbol for the Reagan years about to come.

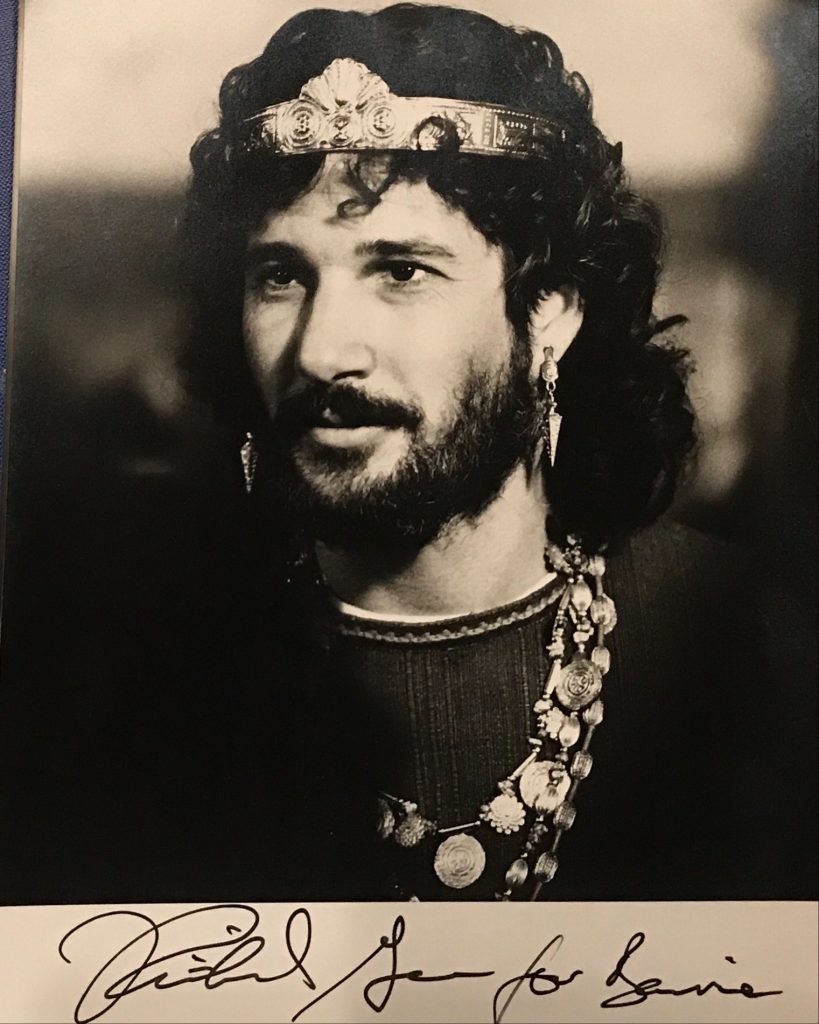

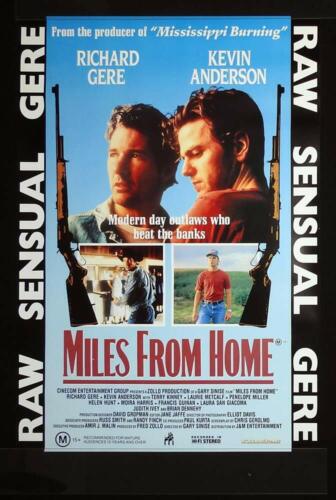

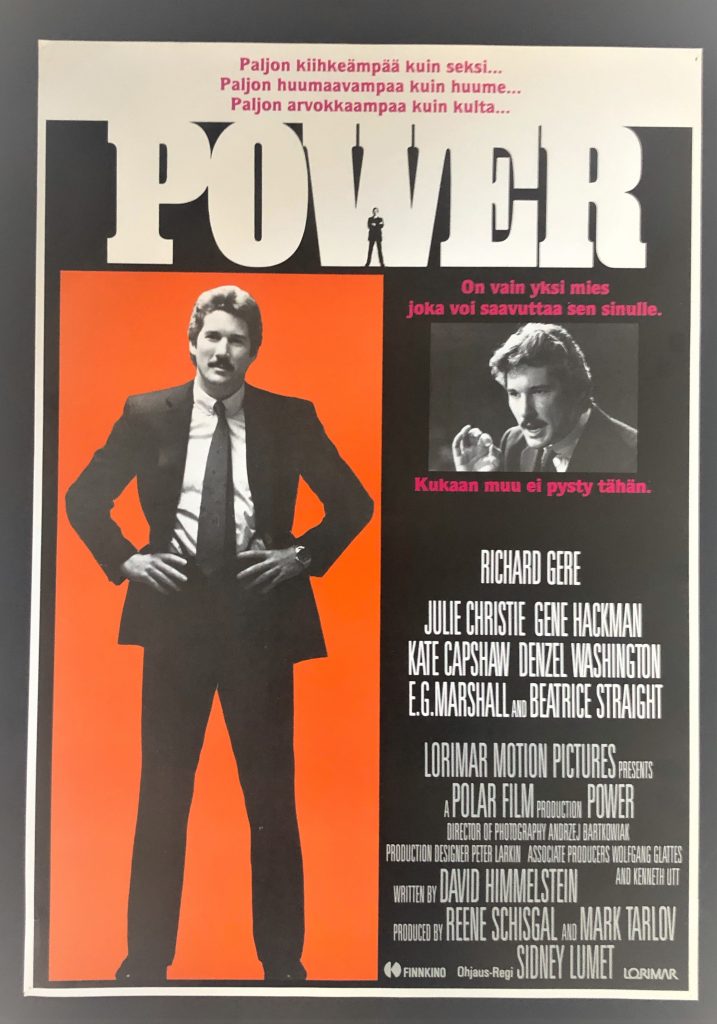

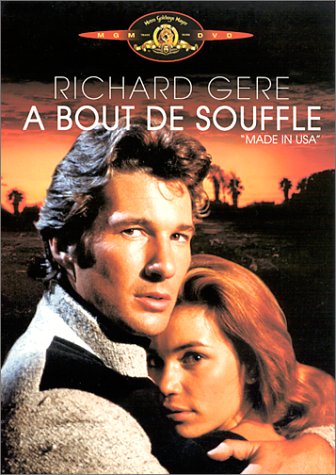

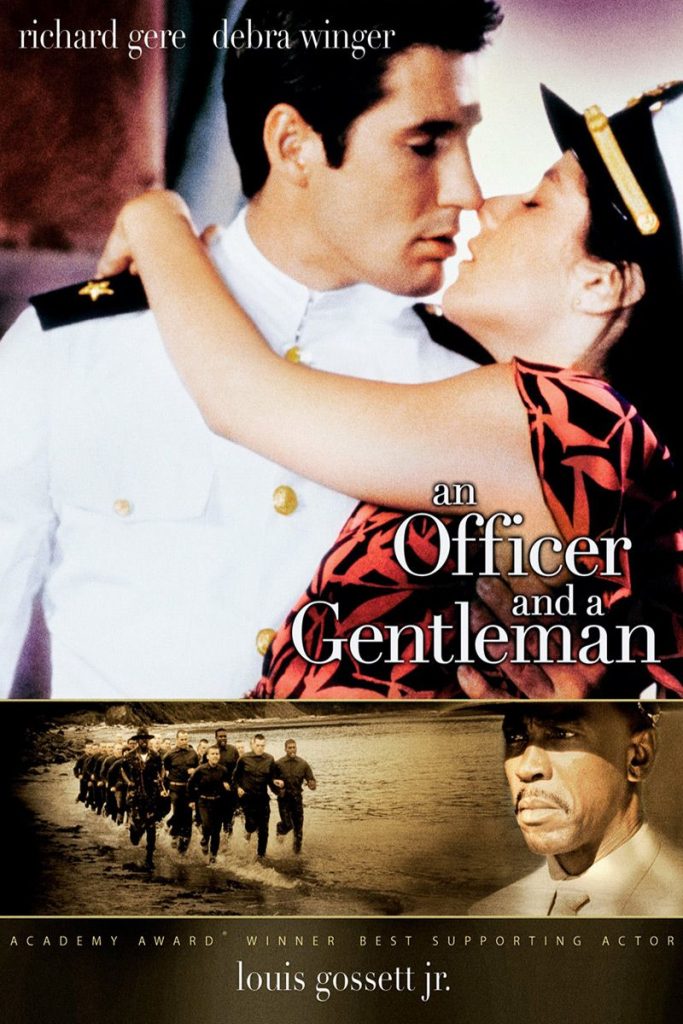

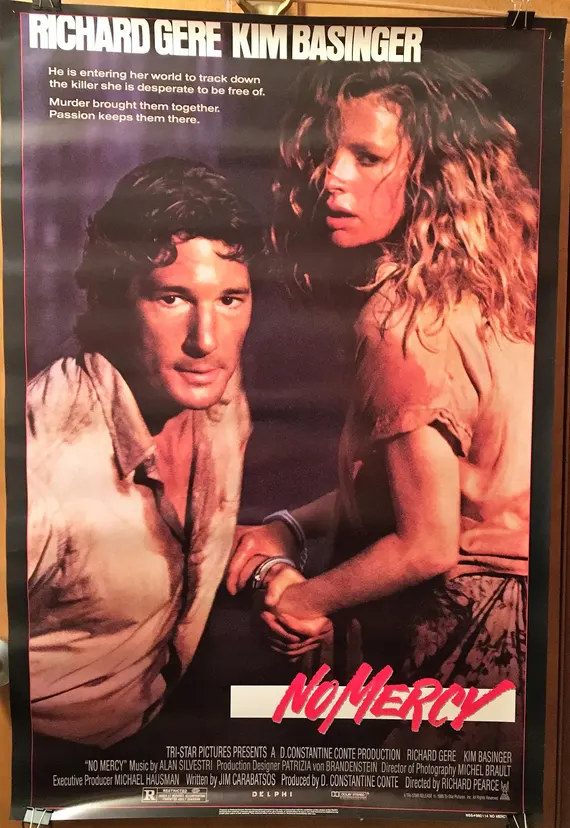

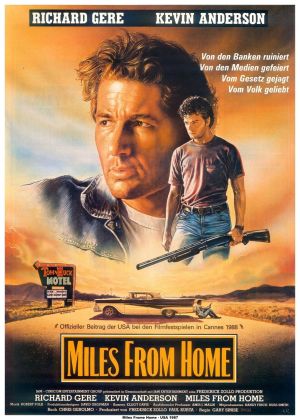

Gere enjoyed his greatest commercial success of the 1980s with “An Officer and a Gentleman” (1982), a surprisingly old-fashioned military romance pairing him with Debra Winger, a co-star with whom he famously fought with off camera. Despite the on-set rancor between the two leads, it did provide combustible chemistry onscreen, culminating with one of filmdom’s most famous scenes: Gere carrying Winger out of the factory, to the tune of “Up Where We Belong.” It had taken a mere five years to reach the top, but he would have little time to savor the altitude. Miscast as a British doctor who becomes involved with South American revolutionaries in “Beyond the Limit” (1983), an adaptation of Graham Greene’s The Honorary Consul, Gere fared no better as an amoral punk in “Breathless” (1983), as his non-stop scenery-chewing and trouser-dropping began growing tiresome at that time. Meanwhile, “The Cotton Club” (1984) proved disastrous from the word go, and a lack of screen chemistry between Gere and sexy co-star Kim Basinger doomed the mindless melodrama “No Mercy” (1986). He turned down blockbusters like “Wall Street” (1987) and “Die Hard” (1988), but his risk-taking – which had paid off with critical raves for his starring turn as a homosexual Holocaust victim in Broadway’s “Bent” (1979) – backfired in failures like “King David” (1985) and “Miles from Home” (1988). In just a few short years, Gere suffered a string of failed movies, casting a spotlight on his early promise now unfulfilled.

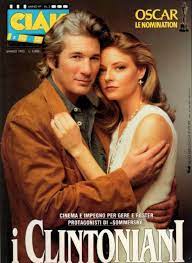

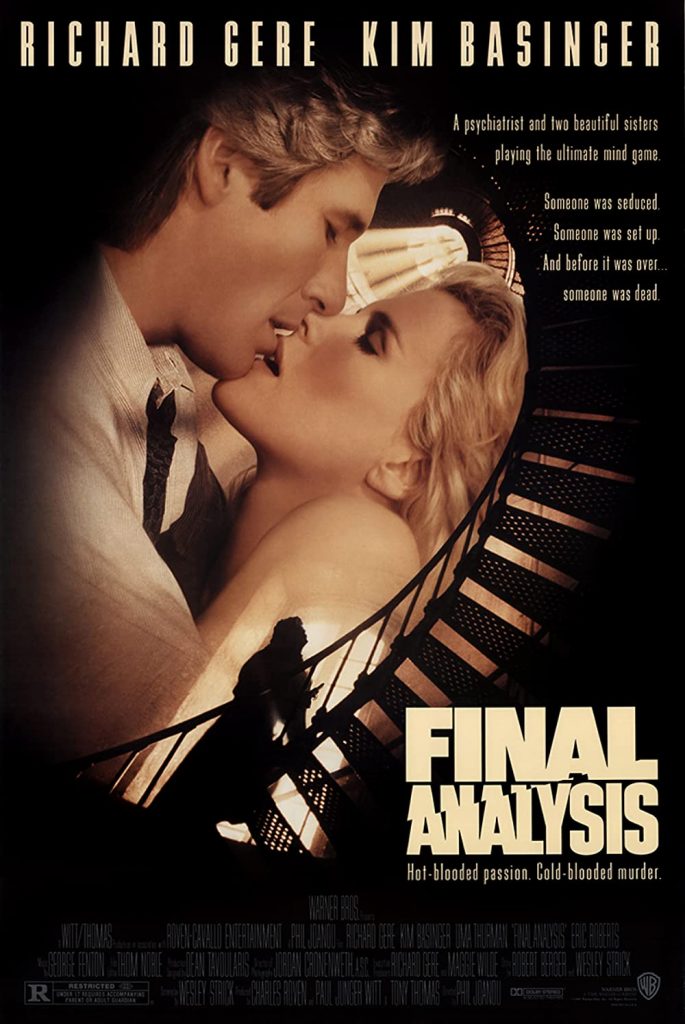

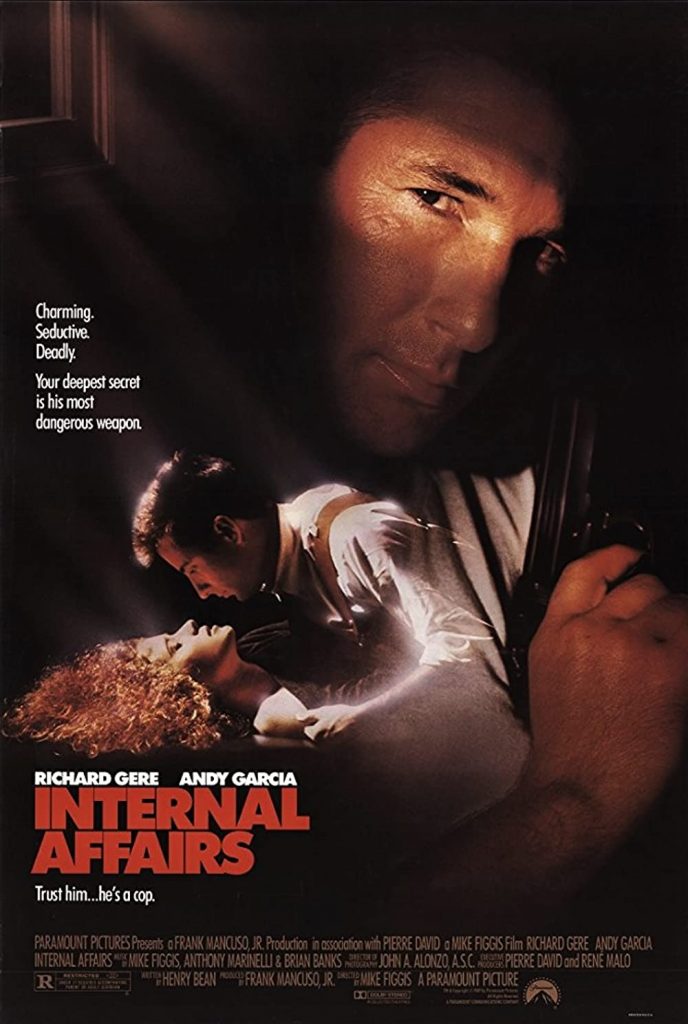

But it took only two years before he reasserted his position as a bankable star with two change-of-pace roles. First, he painted a chilling portrait of corruption and misogyny with his portrayal of rogue cop Dennis Peck in Mike Figgis’ sophisticated thriller “Internal Affairs” (1990), a film which returned him to the homoeroticism of “An American Gigolo.” He followed with the huge box-office success “Pretty Woman,” which allowed him to display a heretofore untapped Cary Grant-like comedic sensibility. There was also no lack of screen chemistry with co-star Julia Roberts; two beautiful people who allowed each other to shine in this updated take on “Cinderella.” Gere went on to play a Eurasian who visits his Japanese relatives in Nagasaki in Akira Kurosawa’s well-intentioned “Rhapsody in August” (1991) before making his executive producing debut with the psychological thriller, “Final Analysis;” a duty he also performed for “Sommersby” and “Mr. Jones” (both 1993). With the exception of “Sommersby,” which co-starred Jodie Foster, Gere was mired in feature failures throughout the early 90s, but his small role as a gay choreographer helped launch HBO’s “And the Band Played On” (1993), earning him an Emmy nomination.

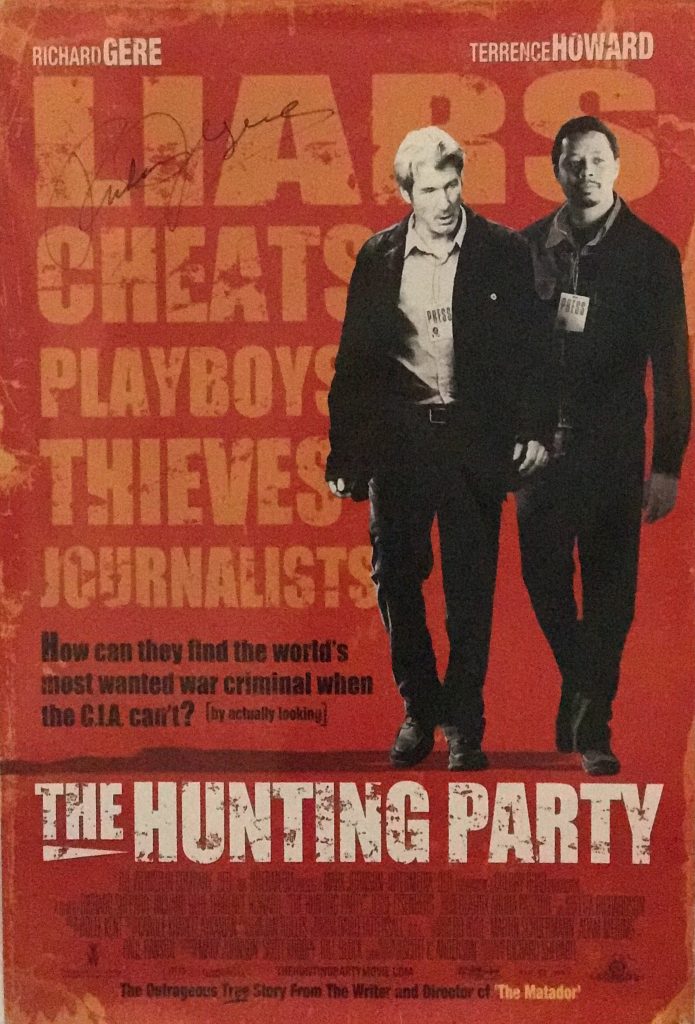

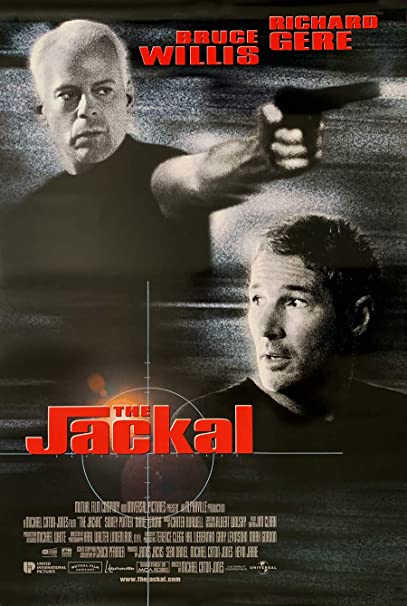

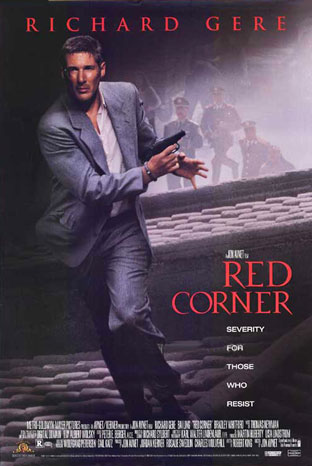

After the embarrassment of his contemporary American-sounding Lancelot in yet another telling of the Camelot story, “First Knight” (1995), Gere returned to form as a cocky attorney defending accused killer Edward Norton in “Primal Fear” (1996). The courtroom thriller “Red Corner” (1997) addressed something close to his heart: the oppressive Chinese regime which had persecuted his beloved Tibet since 1949. Featuring an all-Chinese cast, whose involvement placed their families back home in danger, “Red Corner” told the story of an American entertainment lawyer (Gere) railroaded by a brutal, arcane judicial system. He followed quickly that same year with “The Jackal,” playing a former IRA commando hunting a noted terrorist (Bruce Willis) in this loose remake of Fred Zinneman’s “The Day of the Jackal” (1973). Meanwhile, Gere’s continued promotion of Tibetan Buddhism and its spiritual leader while raising awareness of Chinese repression of the Tibetan culture made him the Hollywood “point man” for high-profile appearances and fundraisers involving the Dalai Lama.

Gere continued to act steadily in movies, though for a stretch his films were less than remarkable. He re-teamed with his “Pretty Woman” co-star Julia Roberts and director Garry Marshall for “Runaway Bride” (1999), a sort-of-sequel-in-spirit, in which he played a journalist investigating the story of a woman who has backed out of several marriages at the altar. The film did well enough at the box office, but the excitement was nowhere near the original Gere/Roberts/Marshall teaming. Worse was the May-December romantic tearjerker, “Autumn in New York” (2000), in which both he and Winona Ryder were seriously miscast against one another in a soggy “dying-girl-finds-love” melodrama. Gere fared much better under the direction of Robert Altman in the seriocomic “Dr. T and the Women” (2000), playing a handsome gynecologist who seems beset by the many demanding women in his life, including his wife, daughters, office staff and patients. Gere was perfectly believable as a man who lures females into his orbit, yet fails to understand what drives them; nevertheless, it was one of Altman’s entertaining but trifling efforts and never lured a large audience.

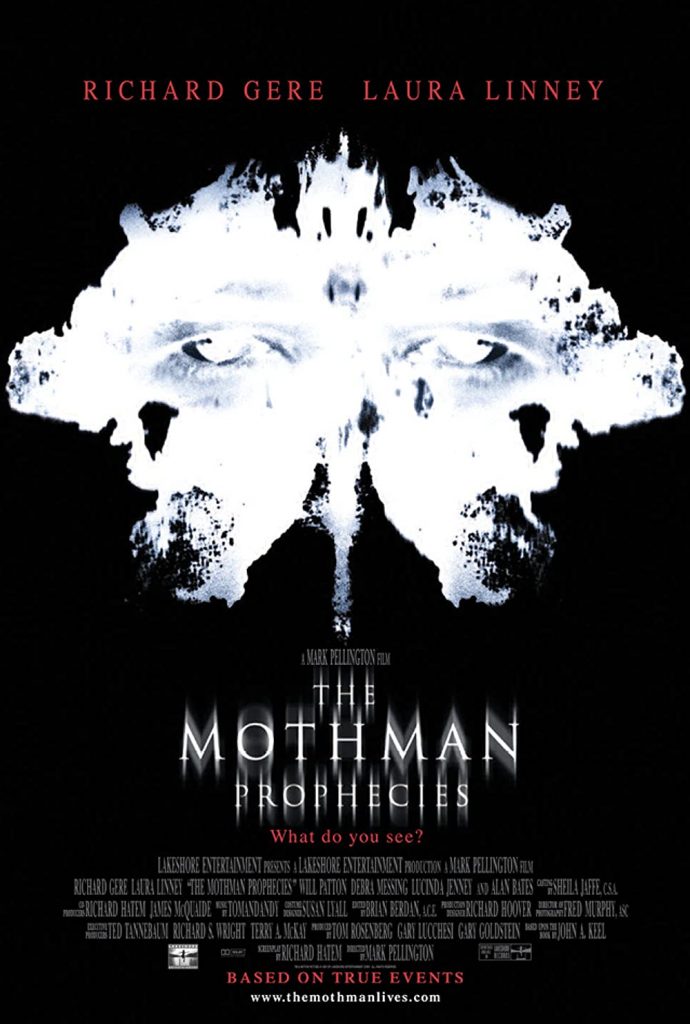

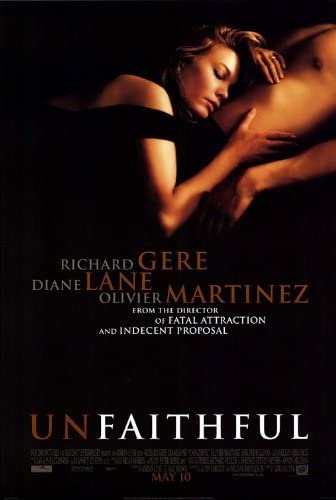

In 2002, Gere starred in “The Mothman Prophecies,” a horror thriller pairing him with Laura Linney that disappeared from theaters with nary a ripple. His next project, “Unfaithful” (2002), brought Gere back to the fore, playing the loving, attentive and dashing husband whose beautiful wife (Diane Lane) nevertheless cheats on him with a sensual Frenchman (Olivier Martinez). The film offered one of the best, most measured performances of the actor’s career, particularly when the truth is finally revealed to him. Gere next got to display his oft-ignored musical talents in the much-anticipated movie version of the musical “Chicago” (2002), playing the slick huckster of a lawyer Billy Flynn, in a role that earned him several award wins, including a Golden Globe for Best Actor – Musical or Comedy. Around this same time, he married his companion of seven years and the mother of his son, actress Carey Lowell. His previous marriage to supermodel Cindy Crawford, while perfect fodder for the tabloids, what with the natural beauty of both on full display, had shockingly ended in 1994 after the couple had been together since 1988.

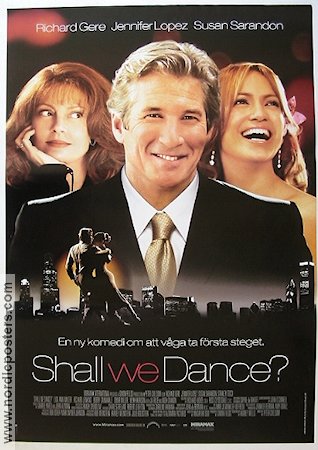

Now in his mid-fifties, Gere still cut a dashing enough figure to be believably paired opposite Jennifer Lopez for the romantic comedy, “Shall We Dance?” (2004), playing a family man who becomes obsessed with reigniting the passion inside Lopez’s chilly dance instructor, while simultaneously discovering the joy of dance himself. He then received mixed reviews for his role in “Bee Season” (2005), playing Saul Naumann, a family man previously distracted by his religious studies of the traditional cabala who bonds with his daughter (Flora Cross) when she becomes a champion speller. Though many critics admired the film and the performance, some took Gere to task for not convincingly portraying the character’s intellectual inner life, as well as not making a convincing Hebrew due to his WASP-y looks and his famous Buddhist beliefs.

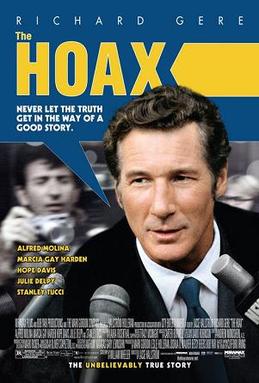

The actor made yet another return to form with his next film, “Hoax” (2007), the true story of faux Howard Hughes biographer Clifford Irving (Gere). In 1970, Irving claimed he had permission to be the biographer of the reclusive and enigmatic Hughes, landing a six-figure advance from publisher McGraw-Hill. Irving later handed the publisher a finished manuscript, which was eventually snuffed out by journalists, and later Hughes himself, as being fraudulent. Gere was persuasive as Irving, a performance that earned the actor critical kudos. Meanwhile, Gere made headlines around the world in April 2007, after an incident involving Bollywood actress Shilpa Shetty at an AIDS awareness event in New Delhi. In an impromptu moment, Gere embraced an unsuspecting Shetty, then bent her backwards while profusely kissing her. “The Kiss,” as it was henceforth called, ignited fury across India, with groups of men burning and kicking effigies of Gere in public. Even a judge from the northwestern city of Jaipur issued an arrest warrant for both stars for violating obscenity laws. While Gere apologized as profusely as he had kissed Shetty, the actress expressed concern that her countrymen were overreacting. The arrest warrant was later rescinded after the furor died down.

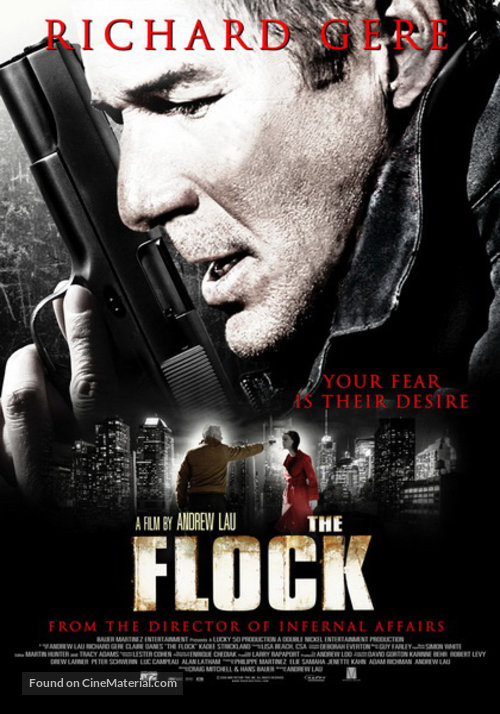

Largely overshadowed by the recent controversy was Gere’s appearance with Claire Danes as a Public Safety agent obsessed with locating a kidnapped girl in the grim mystery “The Flock” (2007). The first English language film directed by noted Hong Kong director Andrew Lau, it was given a wide theatrical run internationally, although it would only be released on DVD the following year in the U.S. Capping off an exceptionally busy year, he also appeared as one of several different metaphorical variations of Bob Dylan in the experimental biopic “I’m Not There” (2007), co-starring Heath Ledger, Christian Bale and Cate Blanchett as other interpretations of the folk-rock legend. The following year saw the always dependable leading man in familiar territory opposite Diane Lane in an adaptation of novelist Nicholas Sparks’ romance “Nights in Rodanthe” (2008) prior to taking on the role of George Putnam, husband of America’s most famous pioneering aviatrix (Hilary Swank) in the historical biopic “Amelia” (2009). Another effort that performed reasonably well overseas, yet only saw a DVD release stateside, was “Hachi” (2009), a based-on-fact inspirational drama about a young Akita puppy who forms an unbreakable bond with an American professor (Gere) after being abandoned at a train station.

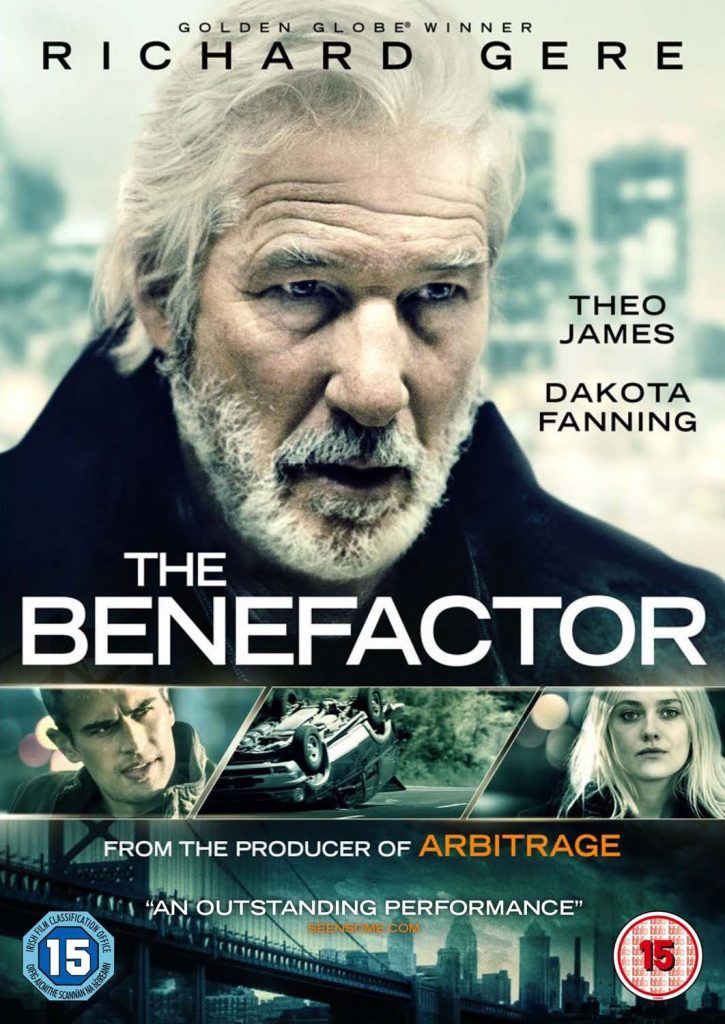

Gere next starred alongside Don Cheadle, Ethan Hawke and Wesley Snipes in director Antoine Fuqua’s gritty police drama “Brooklyn’s Finest” (2010) as a cynical cop facing a crisis of conscience in the weeks leading up to his retirement. Unfortunately, while Gere and his co-stars earned high marks for their work, the majority of critics felt Fuqua and writer Michael C. Martin delivered little more than genre clichés and a bloody climax. After a co-starring turn alongside Topher Grace in the unremarkable spy thriller “The Double” (2011), Gere delivered what many pundits considered to be among his very best in the character drama “Arbitrage” (2012). Cast as a hedge fund billionaire whose professional and personal worlds begin to crumble around him as he attempts to cover up a fatal accident, Gere brought to life a man of fascinating contradictions nearing the end of his rope with intensity and believability. He received a Golden Globe nomination for Best Actor for his work in the film. The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

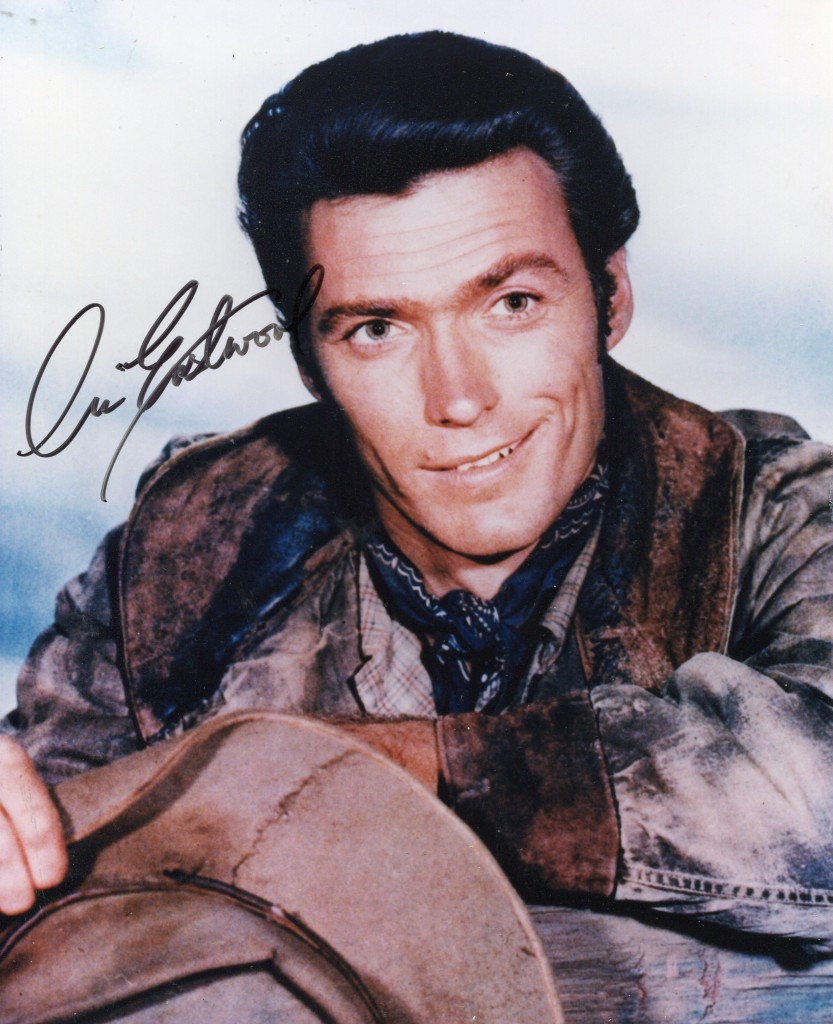

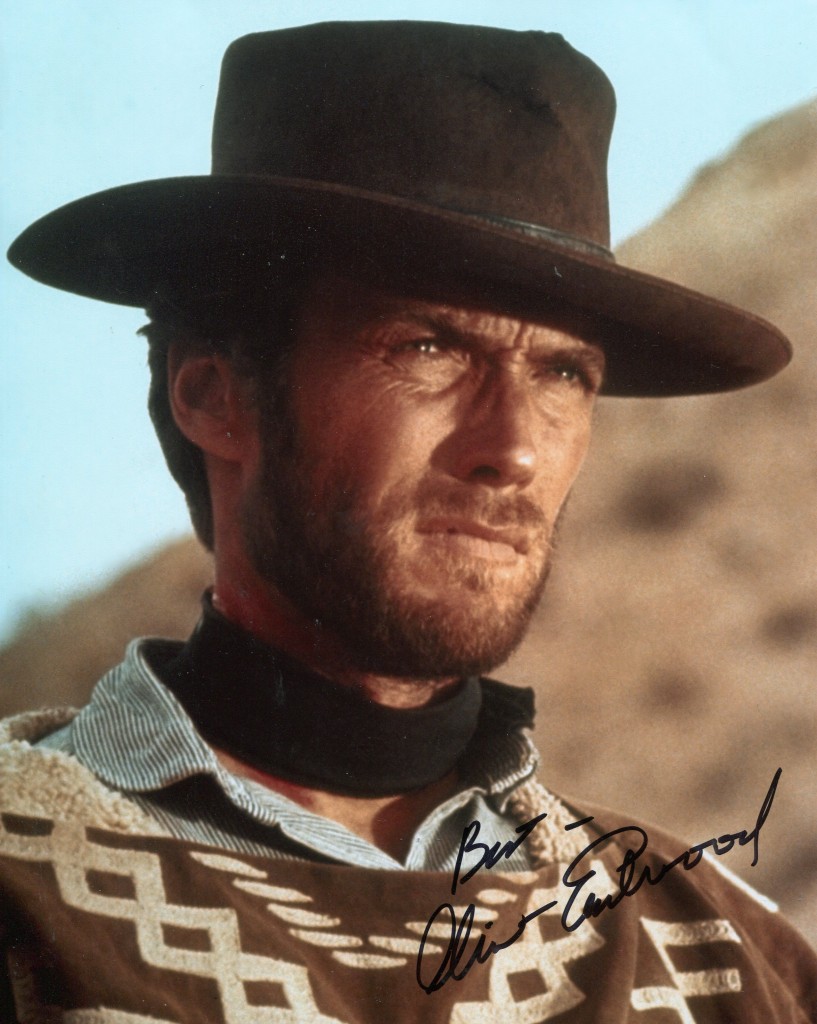

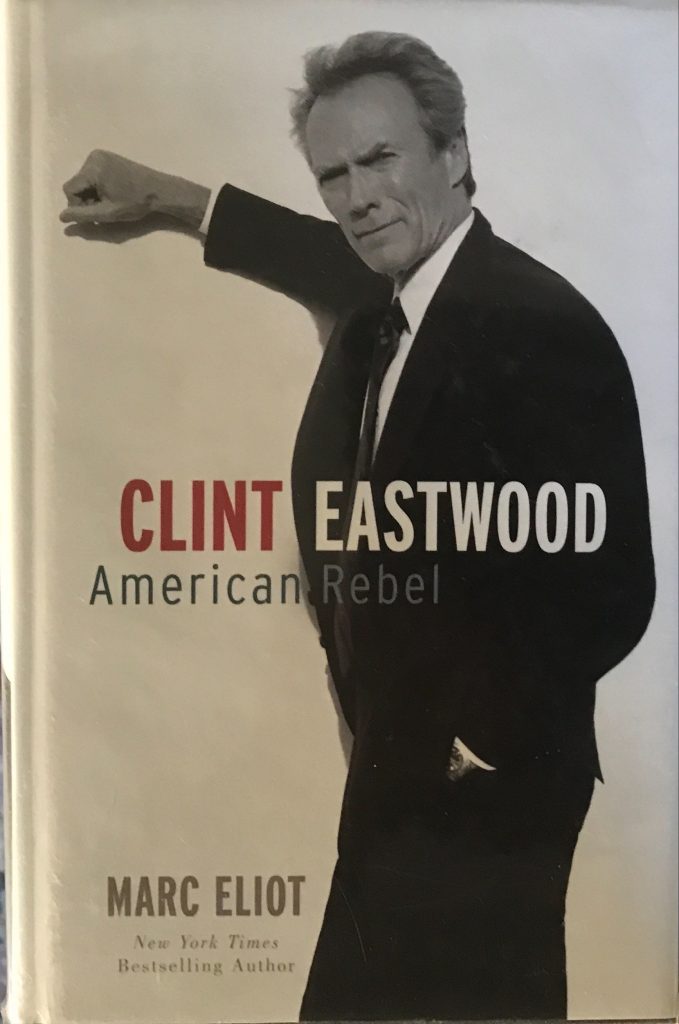

Eastwood is my very favourite actor. Born in San Francisco in 1930, the length of his career is amazing. From his debut in 1955 in “Revenge of the Creature” to 2012 and “Trouble With the Curve, he has consistently shone in the movies. I particularily like “A Fistful of Dollars”, “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly”, “Where Eagles Dare”, “Play Misty For Me”, “Dirty Harry”, “Thunderbolt and Lightfoot”, “The Bridges of Madison County” and “Gran Torino”. Long may he continue.

TCM Profile:

Survey the iconic leading men through every generation of Hollywood filmmaking, and you’d be hard-pressed to find one who has been as durably bankable as Clint Eastwood. Literal generations of devoted fans have been snared by the considerable charisma of the tall, athletic figure with the demeanor as leathery as his features, the less-is-more approach to his craft, and unforgettable portfolio of implacable cowboy and cop heroes. His star clout also enabled him to start a remarkable career behind the camera, and the years have seen him lend an ever-more assured directing touch to many personal projects as well as his more familiar genre efforts.

Clinton Eastwood, Jr. was born in San Francisco on May 31, 1930, to a steelworker father who kept the family transient through the era of the Depression as he searched for steady employment. The Eastwoods ultimately settled in Oakland, where Clint graduated high school in 1948. He spent the next several years of his life rather aimlessly, as he pursued a string of menial jobs from pumping gas to digging swimming pools to playing piano in honky-tonks. In 1950, he entered the U.S. Army, and served as a swimming instructor. Among his fellow servicemen stationed at Fort Ord were actors David Janssen and Martin Milner, who suggested that Clint consider Hollywood after his discharge.

Thereafter, Eastwood enrolled in Los Angeles City College as a business major on the GI Bill; he would never complete his studies. Marrying the former Maggie Johnson in 1953, Clint would finally get his foot in the door with Universal the following year. The studio signed the novice actor for $75 a week, and he logged his first screen time with small roles in Revenge of the Creature, Francis in the Navy and Tarantula (all 1955). Universal cut him loose after a year, but Eastwood persevered over the next few years, continuing to do odd jobs in between sporadic studio assignments.

His first big break came in 1959, when he successfully auditioned for the CBS Western series Rawhide. The show enjoyed a seven-year run, and his stint as cattle driver Rowdy Yates made his name with American TV fans. It was while Rawhide was on production hiatus in 1964 that Clint made a sojourn to Spain, piqued by a screenplay that transferred Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) to the American West. His performance as the taciturn and deadly Man With No Name in Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964) became a European smash hit. Leone would lure him back abroad to reprise the gritty character in For a Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966). Once the trilogy came to American screens in 1967, Eastwood enjoyed cinema superstardom in his homeland as well.

Now a hot commodity, Eastwood was swiftly adopted by Tinseltown as a contemporary cowboy hero, headlining sagebrush stories like Hang ‘Em High (1968) and Coogan’s Bluff (1968), the latter of which started his long-running and influential collaboration with director Don Siegel. He weathered the notorious disaster ofPaint Your Wagon (1969) to headline memorable Westerns and war movies like Where Eagles Dare (1968),Two Mules For Sister Sara (1969) and Kelly’s Heroes (1970).

1971 was a watershed year in Clint’s career in many respects. First, he made the film that he has long considered his personal favorite, Siegel’s unusual Gothic drama, set during the Civil War – The Beguiled(1971). Next, he got his distinguished directing career underway, and also played the lead role of a stalked disc jockey, in Play Misty For Me (1971). Finally, he put in his debut appearance as the Magnum-wielding maverick police lieutenant Harry Callahan in Siegel’s Dirty Harry (1971). The film made him a fixture in the crime action genre and paved the way for four more Callahan shoot-’em-ups (Magnum Force (1973); The Enforcer (1976); Sudden Impact (1983); The Dead Pool (1988)).

Eastwood’s touch continued to prove golden through the ’70s, whether he turned his attention to Westerns (The Outlaw Josey Wales(1976)), action/comedy (Every Which Way But Loose (1978)), or thriller (Escape From Alcatraz (1979)). By the mid-’80s, his marriage to Maggie had ended, and the environmentally conscious star was devoting attention to responsibilities like his two-year stint as mayor of Carmel, California. As the ’80s wound down, the director Eastwood continued to receive critical praise for personal projects such as Bird(1988) and White Hunter, Black Heart (1990), but his familiar star vehicles became less and less of a guaranteed draw.

The rumors of his professional demise were quickly squelched by the success of his revisionist westernUnforgiven (1992), which landed Oscars® for Best Picture and Best Director. He followed up solidly with the successful suspenser In the Line of Fire (1993) and the adult romance The Bridges of Madison County(1995). Into the new millennium, he doggedly continued to portray men of action in the twilight of their lives, even as the box office returns diminished (Absolute Power (1997); True Crime (1999); Blood Work (2002)).

Romantically linked to leading ladies Sondra Locke and Frances Fisher in the years since his divorce, Eastwood remarried in 1996 to news anchor Dina Ruiz. He has fathered seven children by five different women; he has given screen opportunities to his eldest, Kyle (Honkytonk Man (1982)) and Alison (Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1997)). This past May, he squelched rumors of a sixth Harry Callahan movie, finally admitting his willingness to hang up the holsters at age 73. The Carmel cowboy hasn’t stopped exercising his creative chops, as evidenced by his adaptation of the novel Mystic River (2003) with Sean Penn, Tim Robbins and Kevin Bacon.

by Jay Steinberg

The above TCM Profile can also be accessed online here.

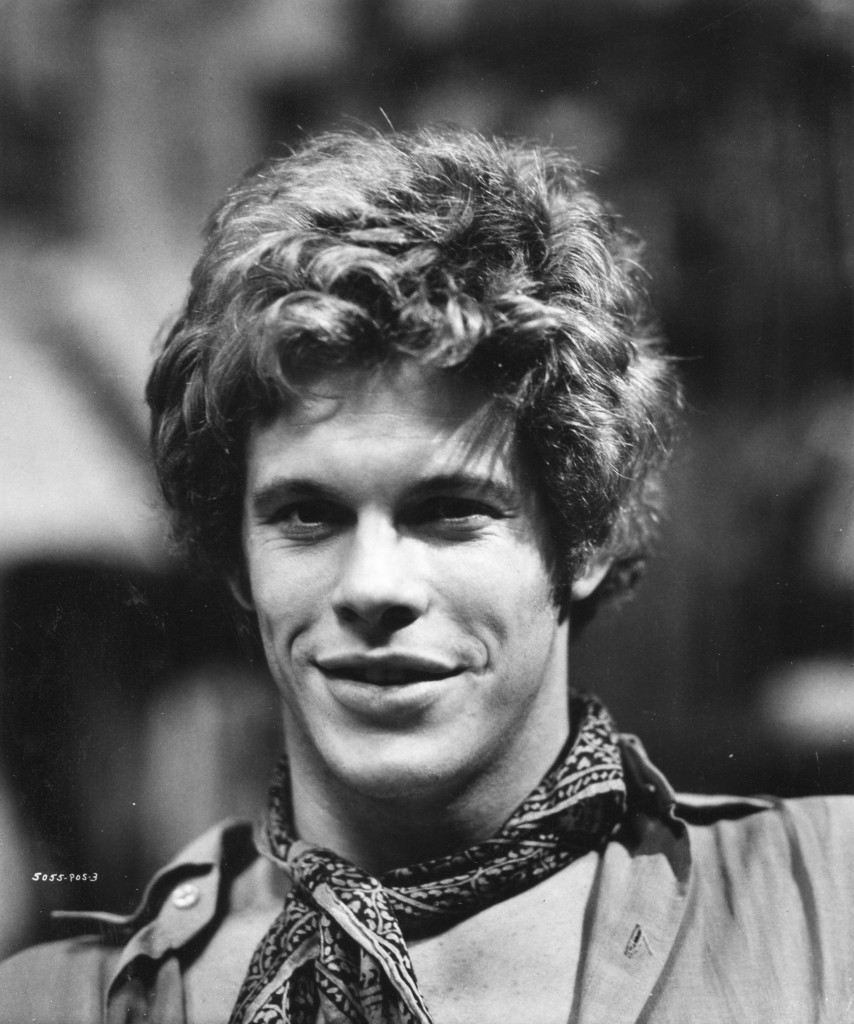

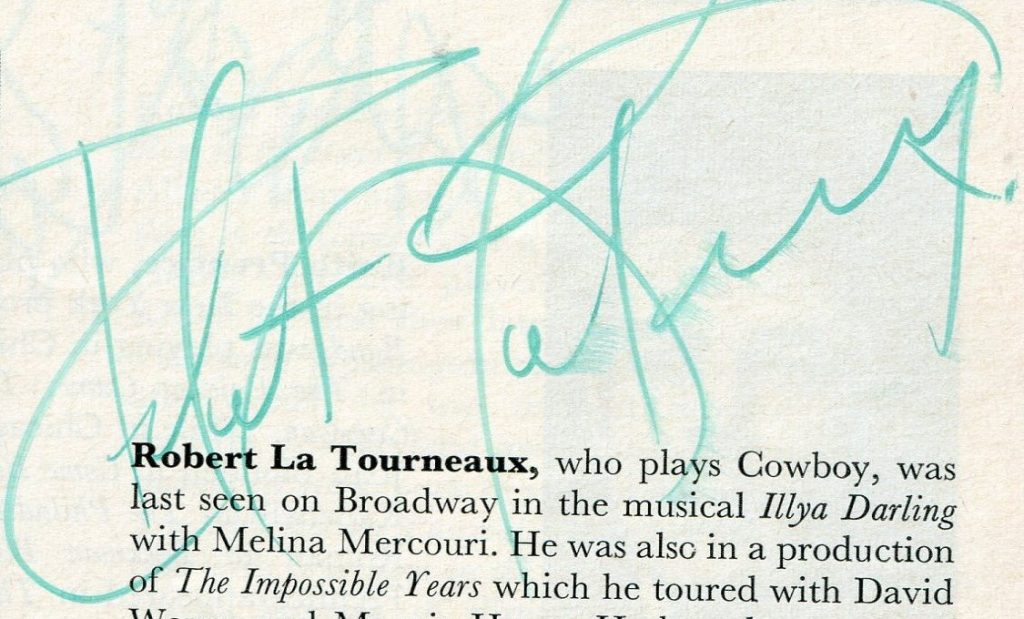

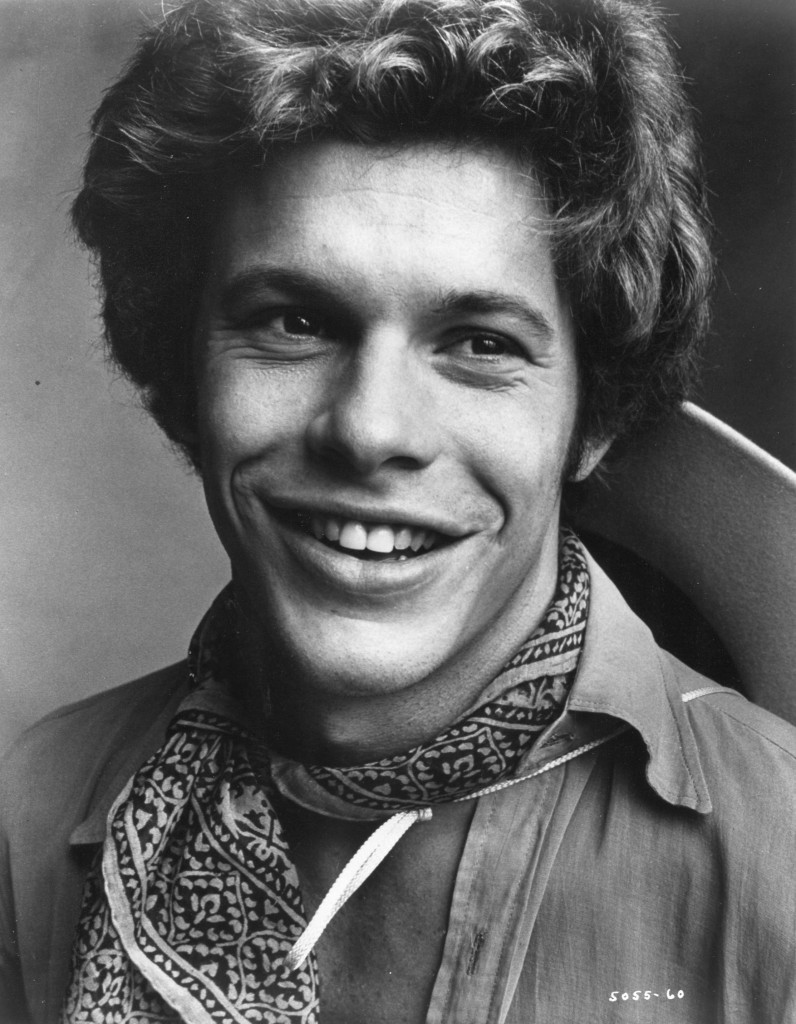

Robert la Tourneaux was born in 1945. He starred in the stage and film productions of “The Boys in the Band”. He died in 1990.

“New York Times” article:

Speaking of the later life of the characters in his “Boys in the Band,” the playwright Mart Crowley speculated that “some of them would have got lost in the night or died. Probably of AIDS.” [ “A Play of Words About a Play,” Oct. 31 ] . Indeed, of the original cast of nine actors, four are known to have died of AIDS. Most recently, there was Kenneth Nelson, who died last month at age 63. Frederick Combs died in 1992 at age 57. Leonard Frey, who was 49, died in 1988. And Robert La Tourneaux died two years earlier at 44.

In “The Boys in the Band” Nelson played Michael, the writer at whose East Side duplex the birthday party was given for Harold (Frey), and Harold’s birthday present was Cowboy (La Tourneaux), a lanky hustler; finally, one of the party guests was played by Combs.

The post-“Band” lives and careers of these actors could not have been more different. For the last two decades of his life, Nelson, a singer-actor from North Carolina, lived in Britain, where he was seen regularly on the stage. He appeared on the West End in “42d Street,” “Showboat,” “Annie” and “Colette.”

Opting for film work, Frey had roles in “Tell Me That You Love Me, Junie Moon,” “Where the Buffalo Roam,” “Tattoo” and other movies, most notably “Fiddler on the Roof,” for which his performance as Motel, the tailor, brought him an Oscar nomination as best supporting actor.

But only the worst of luck came to La Tourneaux. In an interview several years after the 1970 release of the film version of “The Boys in the Band,” he claimed that all doors in Hollywood had remained closed to him. “I was too closely identified with homosexuality, with ‘Boys in the Band,’ ” he said. “I was typecast as a gay hustler, and it was an image I couldn’t shake.” The only movie roles he managed to land were bits in a few low-budget pictures made in Europe.

Late in 1978, La Tourneaux was working in a male porno theater in Manhattan, doing a one-man cabaret act between showings of X-rated films. He said he still believed he could beat the “curse” of his famous gay role and work “straight.” But that didn’t happen. Stricken with AIDS in October 1984, he died on June 3, 1986. It had been 18 years and two months since he had first set foot on stage at Theater Four — handsome and hopeful — in “The Boys in the Band.” DAVID RAGAN New York The writer is the author of “Who’s Who in Hollywood,” a history of motion picture actors.

Noel Harrison was born in London in 1934 and is the son of actor Rex Harrison. He began his show business career as a singer. He went to the U.S. in 1965 and the year after he starred with Stefanie Powers in the TV series “The Girl from U.N.C.L.E.”. He starred with Hayley Mills and Oliver Reed in the movie “Take A Girl Like You”. He had a hit with the song “The Windmills of Your Mind” from “The Thomas Crown Affair” which starred Steve McQueen.

Adam Sweeting’s obituary in “The Guardian”:

Noel Harrison, who has died aged 79 following a heart attack, was the son of the actor Sir Rex Harrison and followed his famous father into show business. He pursued a varied career on stage and in film and television, but it was as a musician that he achieved his moment in the spotlight. In 1968 he recorded the song The Windmills of Your Mind for the soundtrack of the Steve McQueen/Faye Dunaway film The Thomas Crown Affair and it became a top 10 hit in the UK the following year.

“Recording Windmills wasn’t a very significant moment,” he recalled. “It was just a job that I got paid $500 for, no big deal. The composer, Michel Legrand, came to my home and helped me learn it, then we went into the studio and recorded it, and I thought no more about it.” It went on to win an Oscar for best original song. (Coincidentally, Talk to the Animals, the song sung by Rex Harrison in Doctor Dolittle, had won the Oscar the previous year.)

“People love [Windmills],” said Noel, “and it’s great to have a classic like that on my books.” His pleasure was marred only slightly by the fact that he could not perform it at the Oscar ceremony because he was in Britain filming Take a Girl Like You (1970).

Noel was born in London to Rex Harrison and his first wife, Collette Thomas; they divorced when he was eight. He attended private schools, including Radley college, Oxfordshire, and when he was 16 his mother invited him to live with her in Klosters, Switzerland. He jumped at the chance, which allowed him to develop his gifts as a skier. He became a member of the British ski team and competed at the Winter Olympics in Norway in 1952 and Italy in 1956.

After completing his national service in the army, Harrison concentrated on learning the guitar and in his 20s made a living travelling around Europe playing in bars and clubs. In 1958 he was given a slot on the BBC TV programme Tonight, on which he would sing calypso-style songs about current news events.

In 1965 he left for the US with his first wife, Sara, working on both coasts as a nightclub entertainer. He scored a minor hit with his version of the Charles Aznavour song A Young Girl (of Sixteen), which also featured on his first studio album, Noel Harrison, released in 1966. Then he landed a leading role in the TV series The Girl from U.N.C.L.E., playing Mark Slate opposite Stefanie Powers as April Dancer, though the show lasted for only one season.

Harrison’s high profile earned him a recording deal with Reprise, for whom he made three albums, Collage (1967), Santa Monica Pier (1968) and The Great Electric Experiment is Over (1969), and notched another minor hit with Leonard Cohen’s song Suzanne. He also toured with Sonny & Cher and the Beach Boys. However, while his career flourished, his marriage was disintegrating, and Sara returned to Britain with their three children. In 1972 Harrison, beguiled by the back-to-the-land spirit of the era, left Los Angeles for Nova Scotia, Canada, with his second wife, Maggie. There they built their own house and lived on home-grown fruit and vegetables.

He now earned a living from hosting a music show on CBC, Take Time, and took several stage roles in touring musicals including Camelot, The Sound of Music and Man of La Mancha. He even played Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady, which had been an Oscar-winning film role for his father. “I went to see my dad in New York and I said ‘I really need the money, so how do you feel about it?’ He said ‘Oh why not? Everybody else is doing it.'” In the 80s he also staged a one-man musical, Adieu Jacques, based on the songs of Jacques Brel.

He ventured into screenwriting, penning episodes of two “erotic” TV series, Emmanuelle, Queen of the Galaxy and The Adventures of Justine, before returning to Britain in 2003 with his third wife, Lori. They originally planned a short visit to his stepdaughter, Zoe, who was running a cafe in Ashburton, Devon, but liked it so much they decided to stay. Harrison played gigs in village halls across Devon and in 2011 performed at the Glastonbury festival. He released two new albums, Hold Back Time (2003) and From the Sublime to the Ridiculous (2010), and his three Reprise albums were reissued in 2011.

He is survived by Lori and five children from his first two marriages, which both ended in divorce.

• Noel Harrison, actor, musician and writer, born 29 January 1934; died 19 October 2013

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

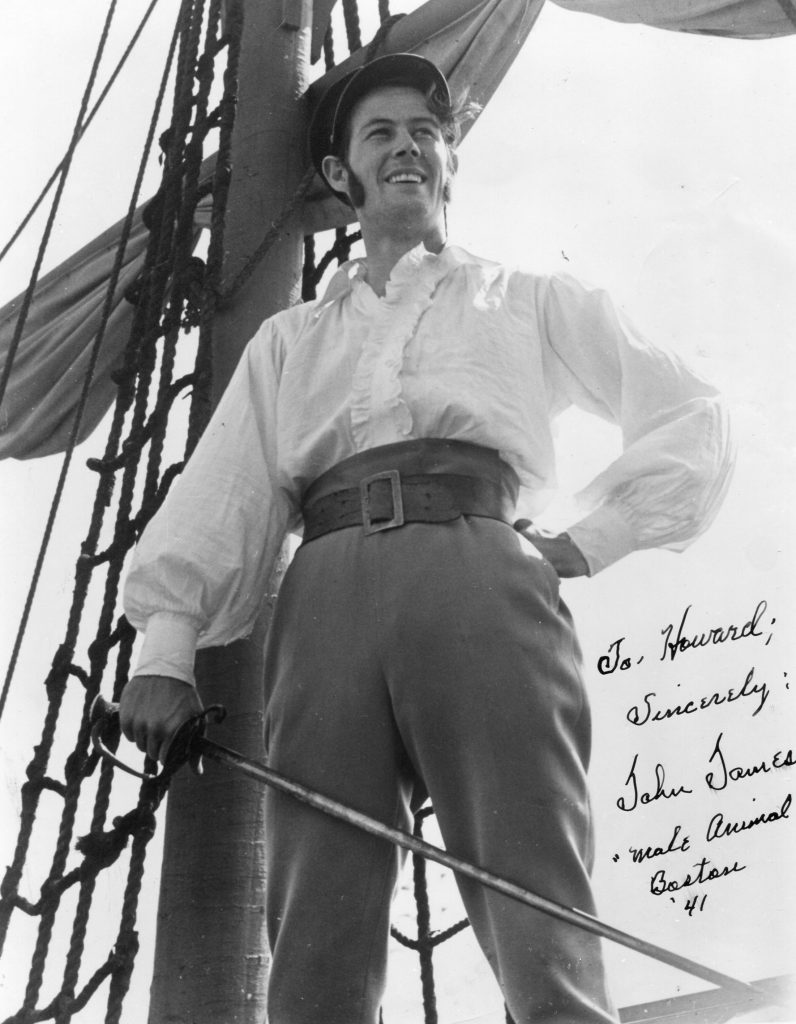

John James was born in 1910. His movies include “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo”, “Outlaw Brand” and “Tap Roots”, He died in 1960.

John James

Llona Massey was born in Budapest in 1910. She came to Hollywood ion 1937 and made movies such as “Rosalie” opposite Nelson Eddy, “Frankenstein Meets the Wolfman” and in 1959 “Jet Over the Atlantic”. She died in 1974.

Gary Brumburgh’s entry:

Sultry, opulent blonde Hungarian singer Ilona Massey survived an impoverished childhood in Budapest, Hungary to become a glamorous both here and abroad. As a dressmaker’s apprentice she managed to scrape up money together for singing lessons and first danced in chorus lines, later earning roles at the Staats Opera. A Broadway, radio and night-club performer, she appeared in a couple of Austrian features before coming to America to duet with Nelson Eddy in a couple of his glossy operettas. In the first, Rosalie(1937), she was secondary to Mr. Eddy and Eleanor Powell, but in the second vehicle,Balalaika (1939), she was the popular baritone’s prime co-star. Billed as “the new Dietrich,” Ms. Massey did not live up to the hype as her soprano voice was deemed too light for the screen and her acting talent too slight and mannered. She continued in non-singing roles in a brief movie career that included only 11 films. For the most part she was called upon to play sophisticated temptresses in thrillers and spy intrigues.Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943) and Love Happy (1949) with the four Marx Bros. are her best recalled. She appeared on radio as a spy in the Top Secret program and, on TV, co-starred in the espionage series Rendezvous (1952). In the mid-50s she had her own musical TV show in which she sang classy ballads. She became an American citizen in 1946. Married four times, once to actor Alan Curtis, Ms. Massey died of cancer in 1974.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.n

Ilona Massey

Joanne Woodward was an American actor who began his career as a ‘pretty boy’ but quickly developed into a good solid actor with a legacy of fine performances. He was born in 1926 in Hollywood. He had his first major role in “Knock on Any Door” with Humphrey Bogart in 1949. The same year he played Broderick Crawford’s wayward son in “All the King’s Men”. His other notable films include “The Hoodlum Saint”, “The Ten Commandments” and “Exodus”. Married four times, three of his wives were famous actresses., Ursula Andress, Linda Evans and Bo Derek. John Derek died in 1998.

Anyone who knows me are aware that I am a bit of a movie buff. Over the past few years I have been collecting signed photographs of my favourite actors. Since I like movies so much there are many actors whose work I like.