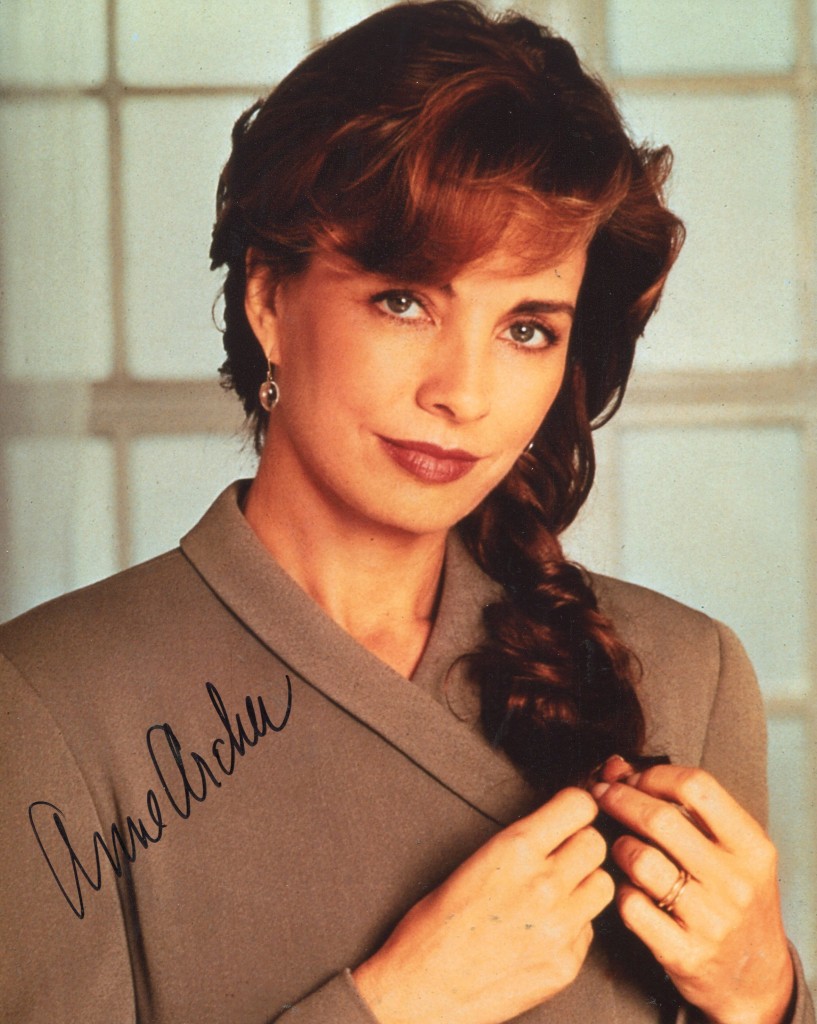

Anne Archer was born in Los Angeles in 1947. She is the daughtor of actors Marjorie Lord and John Archer. She made her film debut in 1972 in “The Honkers”. In 1976 she garnered positive reviews for her performance opposite Sam Elliott in “Lifeguard”. She was nominated for an Oscar for her performance in “Fatal Attraction|” with Glenn Close and Michael Douglas in 1987. Other films include “Raise the Titanic” and “The Narrow Margin” opposite Gene Hackman

TCM overview:

While Anne Archer earned an Academy Award nomination for her supporting performance in the popular 1987 thriller “Fatal Attraction,” it was the actress’ television career that provided the most long-term visibility. She earned her reputation as a loyal wife in big budget movies “Patriot Games” (1992) and “Clear and Present Danger” (1994) opposite Harrison Ford, and on the small screen she starred in countless movies-of-the-week as women coping with the aftermath of divorce, death, remarriage and infidelity. Archer also starred in a number of family-related television series, playing high-powered executive matriarchs on the glamorous dramas “Falcon Crest” (CBS, 1981-1990), and “Privileged” (The CW, 2008-09), proving her versatility as both a vulnerable every-woman and a saucy force to be reckoned with.

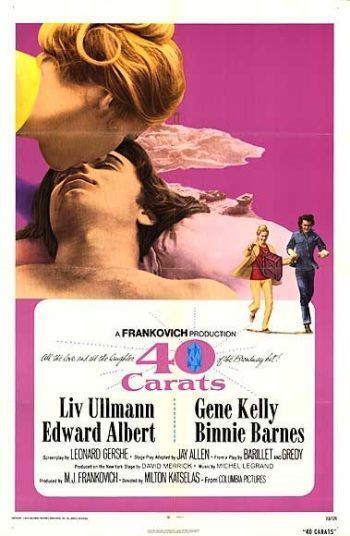

Archer was born on Aug. 24, 1947 in Los Angeles to actor parents John Archer – who appeared in the film classics “White Heat” (1947) and “Rock Around the Clock” (1956) – and Marjorie Lord, who starred as Danny Thomas’ TV wife Kathy “Clancy” Williams on the classic sitcom, “Make Room for Daddy” (ABC, 1953-57; CBS 1957-1964). Young Anne was determined to continue in the family business, and earned a degree in Theater Arts from nearby Claremont Men’s College (now known as Claremont McKenna College). Archer’s professional acting career began with a number of guest television appearances before she was cast as one of the title foursome on the short-lived sitcom version of Paul Mazursky’s feature “Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice” (ABC, 1973). She had a number of supporting film roles in the early 1970s and landed her first screen lead in “Lifeguard” (1976), playing opposite Sam Elliott as a former sweetheart who reconnects at a high school reunion and encourages Elliot’s lifeguard to reexamine his life. Archer studied with Scientologist drama coach Milton Katselas at the Beverly Hills Playhouse in the late 1970s and appeared in a string of movies like Sylvester Stallone’s “Paradise Alley” (1978) and the famous adventure flop “Raise the Titanic!” (1980).

While continuing to average a movie a year, Archer worked steadily in television on the blended family drama “The Family Tree” (NBC, 1982-83) and “Falcon Crest” (CBS, 1981-90), where she made her mark as a duplicitous advertising exec. Archer’s status rocketed from “working actress” to “noted actress” in 1987 with her role as the beautiful, wronged wife of Michael Douglas in Adrian Lyne’s thriller “Fatal Attraction” (1987), who ends up taking out her onscreen nemesis, Glenn Close, with a famous gunshot to the heart. For her work in the seminal 1980s film, Archer was recognized with Best Supporting Actress nominations from the Academy and Golden Globe Awards. Suddenly in demand, she began to field offers for big budget Hollywood features like “Patriot Games” (1992), where she played the beleaguered wife of CIA agent Jack Ryan (Harrison Ford). She followed up with supporting role in the critically lambasted Madonna vehicle “Body of Evidence” (1993), but made a better showing with her role as a children’s party clown at a moral crossroads with her husband (Fred Ward) in Robert Altman’s brilliant ensemble “Short Cuts” (1993), which earned a Best Ensemble Cast award at the Golden Globe Awards.

Archer reprised her role as Harrison Ford’s supportive wife in “Clear and Present Danger” (1994), but the actress spent the majority of the decade playing wives in peril in movies-of-the-week, starring as a recent divorcee in “Because Mommy Works” (NBC, 1994), the new wife of a widower (James Woods) in “Jane’s House” (CBS, 1994), and a woman whose marriage to a writer (Alan Alda) is threatened by his imaginary love life in “Jake’s Women” (CBS, 1996). In a change of pace, the actress played Angelina Jolie’s alluring mother in the independent feature “Mojave Moon” (1996) before resuming her telepic run with “Indiscretion of an American Wife” (Lifetime, 1998) and “My Husband’s Secret Life” (USA, 1998). A pair of thankless roles in the military legal drama “Rules of Engagement” (2000) opposite Tommy Lee Jones, and the action thriller “The Art of War” (2000) opposite Wesley Snipes followed. Archer hit the London stage to essay the sultry Mrs. Robinson in “The Graduate,” and following guest stints on “The L Word” (Showtime, 2004-09) and “Boston Public” (Fox, 2000-04), resurfaced on movie screens as Tommy Lee Jones’ college professor love interest in the comedy “Man of the House” (2005).

After Archer’s portrayal of first lady to president Jack Scalia in the political thriller “End Game” (2006) went straight-to-DVD, the actress returned to television with recurring roles as the socialite mom of Dee and Dennis on the sitcom “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia” (FX, 2005- ) and as the mother of a psychically gifted woman (Jennifer Love Hewitt) on the supernatural drama “Ghost Whisperer” (CBS, 2005-09). In 2006, Archer founded the non-profit organization Artists for Human Rights. She resurfaced on movies screens as the sultry cougar who catches the eye of an irrepressible bachelor (Matthew McConaughey) in “Ghosts of Girlfriends Past” (2009) while at the same time appearing weekly as a jet-setting cosmetics entrepreneur on the glitzy drama “Privileged” (The CW, 2008-09).

By Susan Clarke