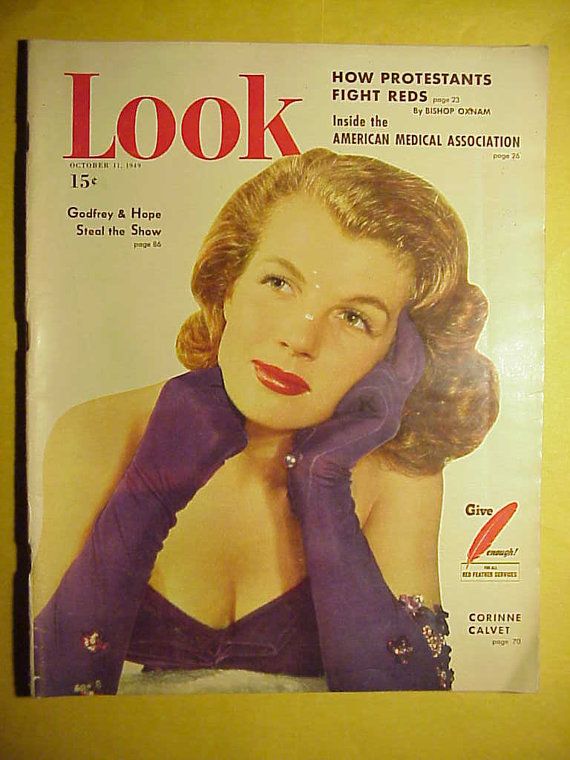

Susan Strasberg obituary in “The Independent” in 1999.

Susan Strasberg was born in New York City in 1938, the daughter of the reknowned Lee Strasberg. She made her film debut in 1955 in “Picnic” as Milly bratty teenage sister of Kim Novak followed by a role in Vincente Minnelli “The Cobweb”. opposite John Kerr. She then retunred to Broadway to win enormous acclaim for the title performance in “The Diary of Anne Frank”. She returned to Hollywood and had a leading role in “Stage Struck” opposite Henry Fonda. Susan Strasberg then made several films in Europe and internationally. She became a very reliable supporting player on film and television. She died in 1999. Article in “Vanity Fair” on Susan Strasberg can be viewed here.

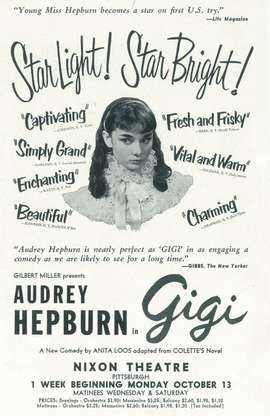

Tom Vallance’s obituary of Susan Strasberg in “The Independent”:The daughter of Lee Strasberg, proponent of the Method and founder of the famed Actors’ Studio, and his wife Paula, who achieved notoriety as Marilyn Monroe’s coach, Susan Strasberg was starring on Broadway in The Diary of Anne Frank at the age of 17; two years later she had the plum role of an aspiring actress in a screen remake of Morning Glory, which in 1933 had won an Oscar for Katharine Hepburn.

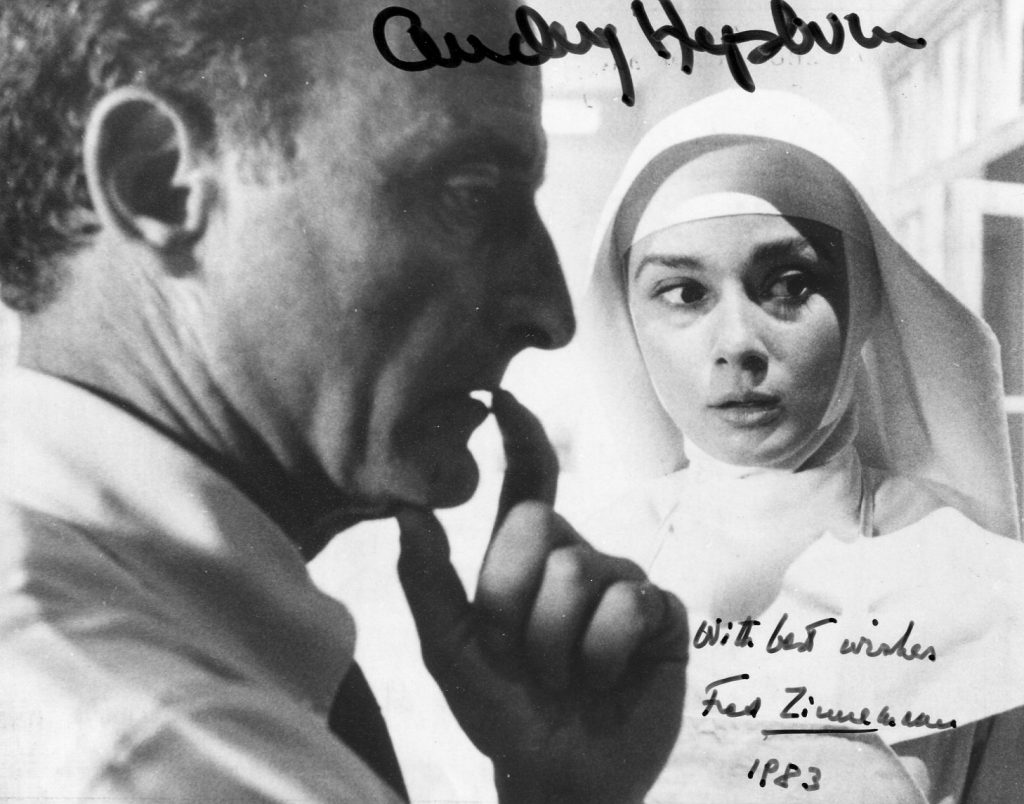

It had seemed as if the beautiful, dark-haired actress might have an impact equal to that made by Jean Simmons and Audrey Hepburn as ingenues, but, though she continued acting in films, theatre, and particularly television, Strasberg’s career never fulfilled its early promise, and her story is one of the sadder ones of show business, both her personal and professional life suffering what the actress herself later referred to as “vicissitudes in fortune”.

Born in New York City in 1938, she attended the High School of Music and Arts, the High School of Performing Arts and the Professional School, and did some modelling before making her stage debut in an off-Broadway play, Maya, at the age of 14. “As far as I can see,” she later said, “about the only thing I’ve missed is a college education.”

In 1953 she made her television debut in Catch a Falling Star on the Goodyear Playhouse, and the following year won praise as Juliet in a live telecast of Romeo and Juliet. Also in 1954, she had a regular role in a fondly remembered though short-lived situation comedy series, The Marriage, which starred Hume Cronyn as a lawyer and Jessica Tandy as his wife with Strasberg as their 15-year-old daughter – the show has the distinction of being the first network series to be telecast in colour.

Strasberg made her screen debut in Vincente Minnelli’s The Cobweb (1955), a static and unpopular portrait of life in a psychiatric clinic, though the scene in which Strasberg and John Kerr (also making his screen debut), as two patients suffering from claustrophobia who give each other courage when they go to a cinema together, was a highlight. The actress was also effective as Kim Novak’s book-worm younger sister in Picnic (1955).

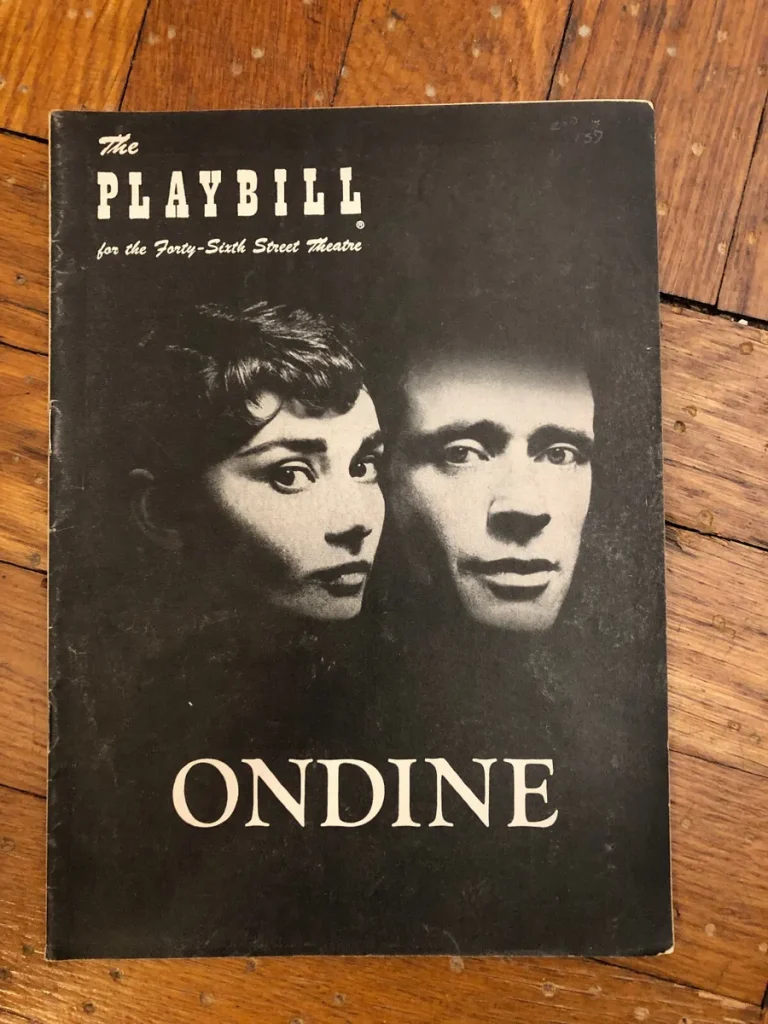

Both films were awaiting release when she was cast as Anne Frank in Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett’s dramatisation of the young girl’s diaries, a role that brought stardom. Brooks Atkinson in The New York Times called her “a slender, enchanting young lady with a heart-shaped face, a pair of burning eyes and the soul of an actress”. Her parents had stayed away from rehearsals and allowed her to be directed by Garson Kanin, and Lee Strasberg stated,

When we saw Susie in action, we were all amazed at her great sensitivity. I just don’t know how she picked it all up. She’s never had any formal training.

Within three months her name was in lights above the title, though Noel Coward, after seeing her wistfully appealing performance, wrote in his diary:

She plays it well, very well indeed, but she knows too much. Poor child, in future years it is to be hoped that she learns to know less.

Strasberg herself, though her childhood had been spent surrounded by theatre folk, had been too young to attend her father’s classes, then after her success did not find the time. “There are so many things I want to do,” she said, “I’m lucky I started young.”

During the two-year run of the play, Strasberg formed a close friendship with Marilyn Monroe, who had been studying with Lee Strasberg and who had come heavily under the influence of Paula Strasberg. “Marilyn used to tell me she envied me having a mother and father,” said the actress. “She said she missed having a home life and parents who cared.” Later Strasberg wrote a book about the friendship, Marilyn and Me – sisters, rivals and friends (1992).

Susan Strasberg’s major chance to attain screen stardom came with her casting as Eva Lovelace, the small-town girl who comes to New York determined to fulfil her destiny as a great actress, in Stage Struck (1955), based on Zoe Akins’s play Morning Glory. Sidney Lumet’s film successfully captured the atmosphere of the incestuous world of the New York theatre, but Strasberg’s mannerisms alienated more viewers than they entranced. (The opposite had been true in 1933, when Hepburn’s equally pronounced mannerisms had annoyed a minority but generally bewitched the public, who flocked to the film, which won her her first Academy Award.)

Strasberg was then bitterly disappointed not to be given the role of Anne Frank in George Stevens’s film of the play, and she later suggested that it was because Stevens was afraid of Paula Strasberg, who was a strong influence on her daughter and who had become intensely disliked in Hollywood because of the trouble she had caused working as a coach for Marilyn Monroe. (Shelley Winters has stated that she went with Stevens to see the play near the end of its two-year run when Strasberg had become “tired and stilted” and this deterred the director. Two years later, with the film nearing production, Winters urged the actress to go to Hollywood and beg to be tested, but she refused in order to stay in New York with her lover Richard Burton.)

Strasberg had returned to the theatre to star with Helen Hayes and Burton in Jean Anouilh’s romantic play Time Remembered (1957), and promptly fell in love with her leading man.

Strasberg and Burton did take an apartment together in New York, but the short-lived affair ended with the actress heart-broken. She confessed later that she had cared too much for the actor, notorious for romancing his leading ladies. Strasberg retained warm memories of Hayes, though: “I was young,” she said. “Miss Hayes really took me under her wing as a woman and actress – and she was fun!” Hayes also had reservations, echoing Coward, of talent blossoming too soon without formal training or the time to accumulate the experience and technique required to sustain a long career.

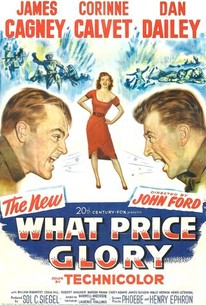

Strasberg next appeared in Shadow of a Gunman (1958) with a group of Actors’ Studio players, though she had still not attended the studio herself. “I could stand it, but I don’t know if my father could,” she said. She was part of the New York City Centre production of Saroyan’s The Time of Your Life that played at the Brussels World Fair in 1958 before becoming a memorable Armchair Theatre presentation on ITV, its cast including Ann Sheridan, Dan Dailey and Franchot Tone besides Strasberg, and the following year she toured with Tone in Caesar and Cleopatra.

In 1961 she was in a British horror film, playing the wheelchair-bound heroine of Seth Holt’s A Taste of Fear, co-starring with Ann Todd, who later commented, “I thought it was a terrible film. I didn’t like my part and I found Susan Strasberg impossible to work with, all that `Method’ stuff.” In The Adventures of a Young Man (1962), based on the autobiographical short stories of Ernest Hemingway, Strasberg was the ill-starred nurse with whom the wounded hero falls in love during the First World War, then she returned to Broadway to play Marguerite Gautier in Franco Zeffirelli’s lush production of The Lady of the Camelias (1963), but her performance was considered wan compared to the indelible memories of Garbo.

Disappointed in her career, Strasberg began to use a variety of drugs, and in 1965, despite having once said, “I’d rather not marry an actor because there isn’t room in the house for two egos”, she married the quixotic young actor Christopher Jones, who was taking LSD. The couple had a daughter, Jennifer, who was born with a congenital birth defect which the actress blamed on the drug-taking. Strasberg and Jones were divorced after just one year of marriage.

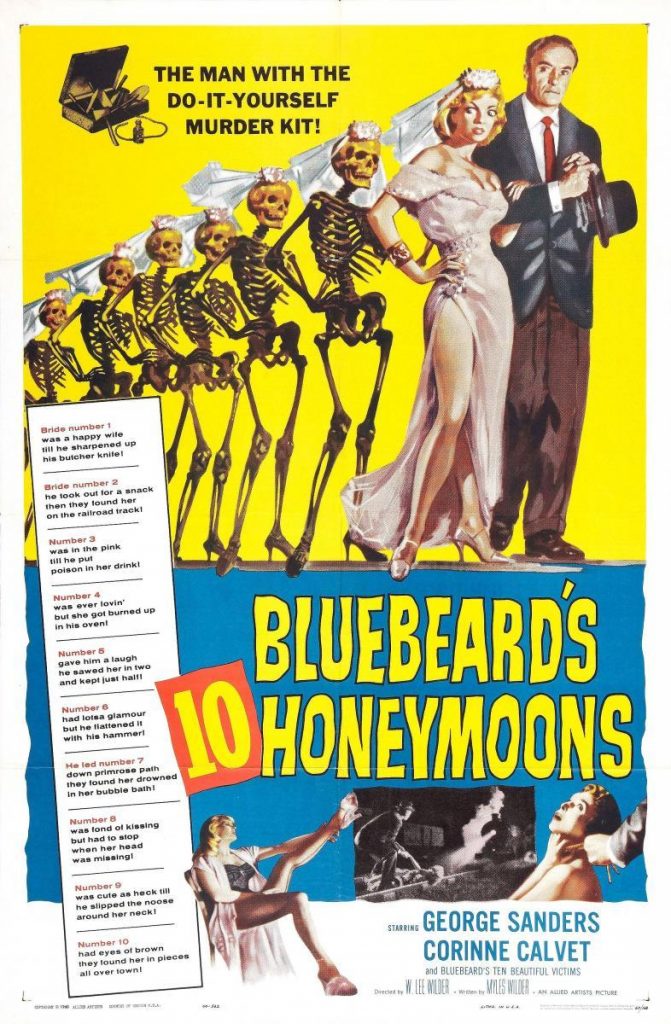

She returned to England to appear as Dirk Bogarde’s love interest in Ralph Thomas’s story of anti- British terrorists in 1954 Cyprus, The High Bright Sun (1966), after which her film career became undistinguished, including some youth exploitation movies for American International (The Trip, Psych-Out) and some films in Italy, where she lived for a while, becoming noted for the poker sessions she held in her large apartment. (“At the beginning, when they thought me a novice, I cleaned out a couple of the boys,” she remarked later.)

An independently produced horror film, Who Fears The Devil? (1973), has acquired a cult reputation as an off-beat tale of hill-billies battling the devil, but The Manitou (1978), in which Strasberg sprouted a foetus on her neck, wasted her talents along with those of such veterans as Tony Curtis, Ann Sothern and Burgess Meredith. Her most prolific work was on television, with countless guest appearances in shows including McMillan and Wife, Streets of San Francisco, The Rockford Files, Cagney and Lacey and Murder She Wrote. In 1980 she wrote an autobiography, Bitter Sweet, because, she said later, her career was “stalled”:

It seemed totally untenable to me, acting for 25 years – I had played Juliet, Cleopatra and Anne Frank – and there I was, sitting in Hollywood just waiting for somebody to want me.

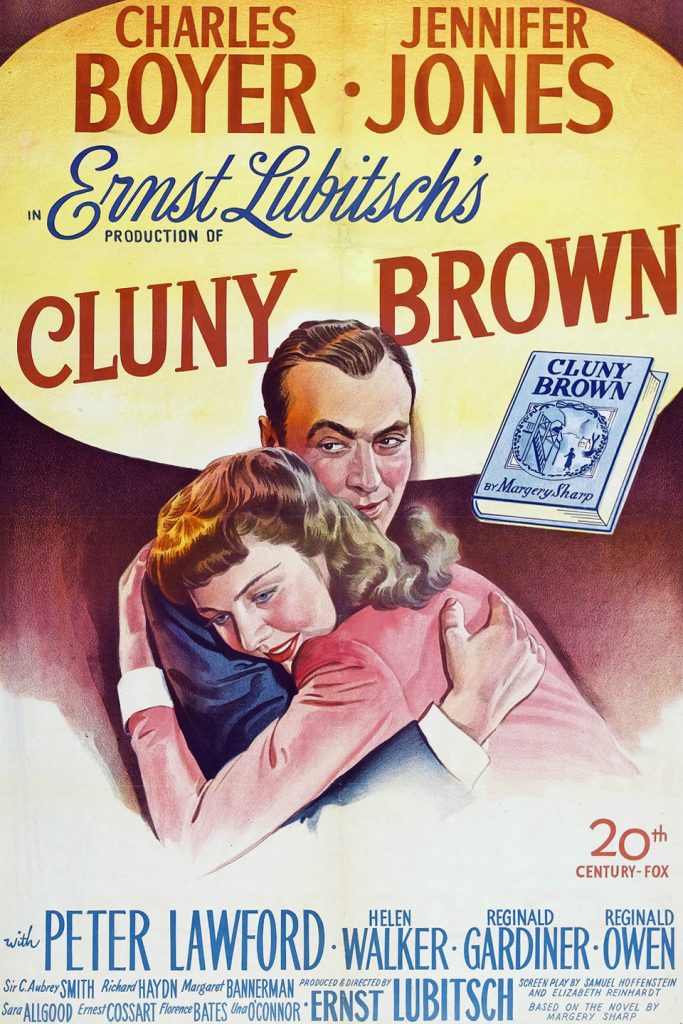

She criticised her father for being preoccupied with his acting classes and her mother for alienating prospective employers with the strong supervisory stance she adopted over her daughter’s work. (Knowing that her father had a crush on Jennifer Jones, the 16-year-old Strasberg had aspired to please her father by emulating Jones’s dark hair and eyebrows. “When I saw photos of myself,” she said later, “I realised with a shock that I resembled a young Jennifer Jones.”)

Among Strasberg’s last films were The Delta Force (1986), in which she was a passenger on a hijacked plane, and Prime Suspect (1989) with Frank Stallone.

Back in 1959, when asked about her future, Strasberg had talked excitedly of plans to do The Wild Duck with Sir Laurence Olivier. But that was just four years after the first night of The Diary of Anne Frank when her triumph had been so emphatic that – Lee, Paula, Susan and Marilyn Monroe having taken their places in Sardi’s restaurant after the show, and before the newspapers had appeared – Franchot Tone stood and asked all the patrons to join him in a toast, saying, “Little Susan, you have been launched on a long and glittering career . . .”

Tom Vallance

Susan Strasberg, actress: born New York 22 May 1938; married 1965 Christopher Jones (one daughter; marriage dissolved 1966); died New York 21 January 1999.