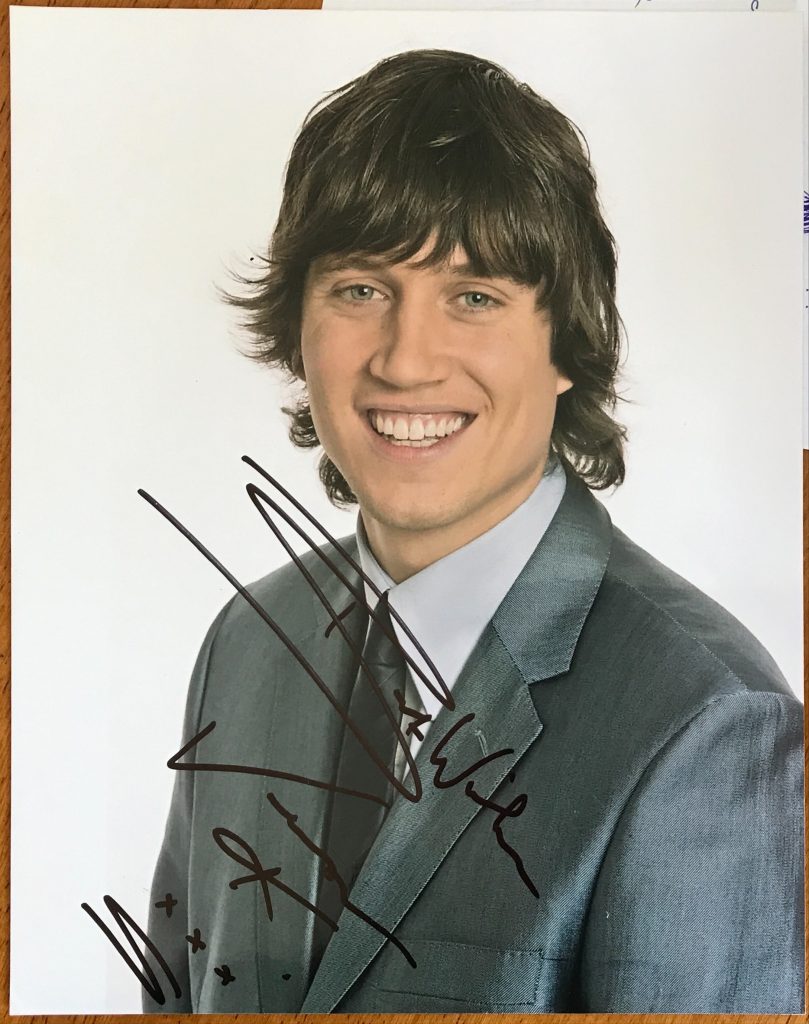

Vernon Kay was born in 1974 in Manchester. He is known for his television work on such British shows as “All Star Family Fortune”. He is married to TV presenter Tess Daly.

Brittish Actors

Vernon Kay was born in 1974 in Manchester. He is known for his television work on such British shows as “All Star Family Fortune”. He is married to TV presenter Tess Daly.

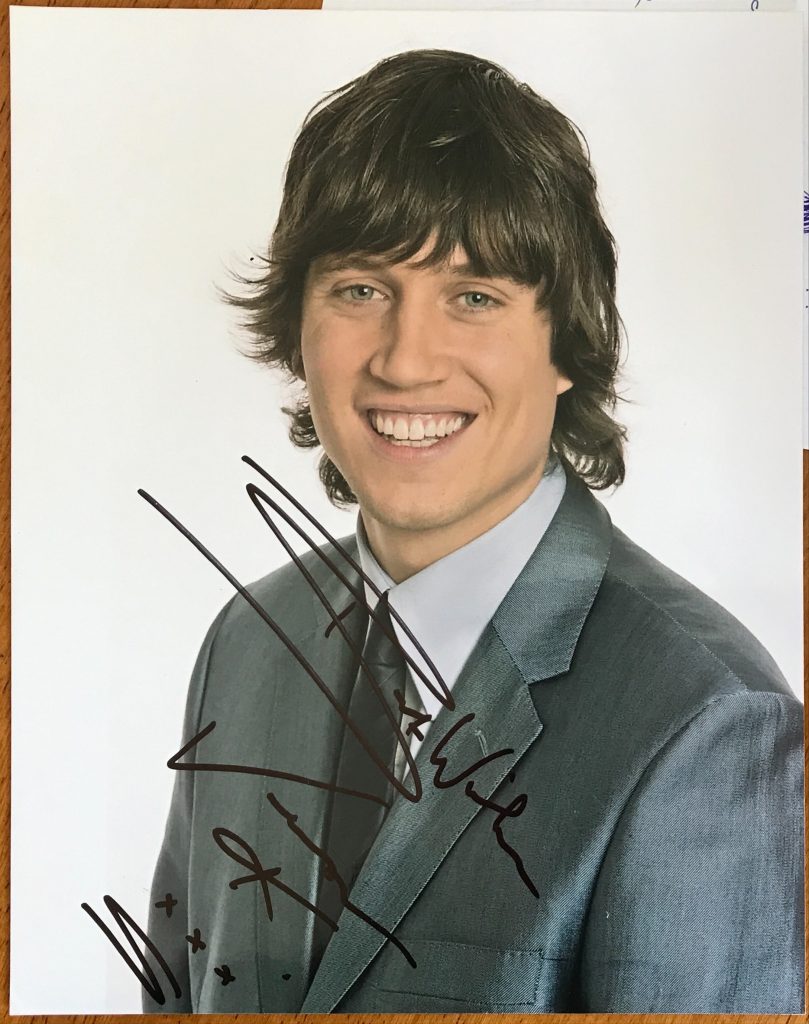

Stephen Haggard was a British actor and poet who was born in Guatemala in 1911. He made his stage debut in Munich in 1930. His films include “Whom the Gods Love” in 1936, “Jamaica Inn” in 1939 and “The Young Mr Pitt” in 1942. He died in 1943 in Egypt during World War Two.

Bryan Ferry is the epitome of style and cool. He was born in Tyne & Wear in the North-East of England in 1945. He was part of the great rock band ‘Roxy Music’ who came to fame in the 1970’s with such classics as “Virginia Plain” and “Do the Strand”. In the 1980’s, ‘Roxy Music’ were eve better with hits like “Avalon” and “Same Old Scene”. On film, Ferry has acted with Cillian Murphy in Neil Jordan’s “Life On Pluto”.

Chris Harvey’s 2013 article in “Telegraph”:

By what strange conjunction of planets did Bryan Ferry find himself creating music for Baz Luhrmann’s spectacular 3D film of The Great Gatsby? The boy from a mining village who grew up to become one of the 20th century’s most impossibly glamorous figures supplying a soundtrack to Fitzgerald’s study of vaulting ambition and the invented self? The gods must appreciate irony, at least, for surely Ferry is Gatsby come to life.

It happened because of the album the former Roxy Music frontman created in 2012 with the Bryan Ferry Orchestra. The Jazz Age features instrumental versions of Ferry’s songs played in the style of Twenties jazz. Luhrmann had almost finished Gatsby when he heard it and got in touch. He persuaded Ferry to add daubs of music throughout the film, including a wonderful backdated update of Beyoncé’s Crazy in Love, with Emeli Sandé, and a recasting of the mournful, bluesy Love Is the Drug that appears on The Jazz Age as a stirring up-tempo number, with Ferry’s voice floating above it like the ghost of New Orleans.

We’re sitting talking about the film the night after Ferry has seen it for the first time. I ask him if Luhrmann’s riot of colour and sound captured the jazz age as he sees it in his imagination. “I kind of see it in black and white,” he laughs. He’s not really a fan of 3D and found himself wanting the odd slower sequence or passage amid the spectacle but looks forward to watching it in 2D, with a rewind button at hand. “I’m quite slow – younger audiences absorb images much faster than somebody of my generation,” he says.

Ferry is 67. It’s more than 40 years since he was beamed down from the Planet Glam to the Top of the Pops stage to sing Virginia Plain in glittery green eyeshadow. Yet even now when he lingers on a word, his eyelids flutter downwards and hover for a few moments before he pulls them up again, just as they did in that performance in 1972. He still has great hair. He’s wearing a blue shirt, darker blue tie, and leaning back on a comfortable sofa. He talks softly, in a voice that is oddly reminiscent of the Prince of Wales. I’m so surprised by this that afterwards I scour YouTube to try to trace the slow vanishing of his Tyne and Wear accent. But no, it seems he has always talked like this. Does he identify with Gatsby?

“Yes, who wouldn’t if you came from a very poor background like mine?” he says. But, as he points out, “it was rich in many ways”. Ferry grew up in Washington, five miles from Newcastle, at the time of the slum clearances in the city. “It’s a very unsophisticated world I grew up in. I would have fancied a house like Gatsby’s,” he adds, “big parties and the sea plane. He had it made really, but the obsession will always get you in the end.”

Ah, the obsession. Fitzgerald’s hero’s rise and his downfall are intimately linked to his obsessive love for the socialite Daisy, a woman he met and fell in love with when he was a penniless soldier. Has there been a Daisy in Ferry’s own life, I wonder.

“That’s a difficult one.” He pauses. “Well, yeah, I identify with his position, yeah.” This is followed by a long silence. “I think there are always things in your life that kind of slip away. Is it fate? Is it meant to be? I guess it’s like that. It’s a good reason, really, for making the most of everything that happens to you. If things in your life do go wrong you’ve got to move on to another thing.”

There have been many women in Ferry’s life. His four children, all boys, are from his 20-year marriage to a London socialite, Lucy Helmore, which ended in the early 2000s. In 2012 he married Amanda Sheppard, a former PR who is 36 years his junior.

Has he experienced Gatsby’s obsessiveness? “Yes, I once had this song, I didn’t call it ‘Slave to Obsession’ but that was one of the key lines. It’s called No Strange Delight, it’s on a Roxy album.” The song is on Flesh and Blood, recorded in 1980, roughly two years after Ferry’s girlfriend Jerry Hall, who had appeared on the cover of the 1975 album Siren, left him for Mick Jagger. The album also includes the delicate pop classic Over You (“Where strangers look for new love, I’m so lost in love – over you.”)

Ferry has written many eloquent songs about love over the years. What has experience taught him about it? “That it’s a bit of a riddle, really. The music that I write is generally quite emotional so it lends itself well to love songs, I don’t want to be singing particularly about wind farms or the war going on here, there or anywhere.

“A lot of the tunes are quite sad as well so without knowing it I get sucked into writing yearning, more intimate songs. Some of the lyrics I’ve done I’ve been very pleased with. It’s by far the hardest part of it but the music that comes out of me tends to be quite melodic, that’s what I think I’m best at, writing melody.” He smiles. “I’m trying to avoid your question as best I can. I don’t know anything about love at all.”

Gatsby, of course, is also about class, about the collision between old money and new. With his country house in Sussex, his house in London and his ability to flit between worlds, I wonder if Ferry feels that he has escaped the boundaries of class altogether. What class does he see himself as? “I’d say classless, definitely, I like to think. The class rigidity that some people still beat themselves up with in this country seems a bit old-fashioned to me now. I do think that standards should be high. I hate dumbing down and I hate political correctness. I identify with the Cavaliers rather than the Roundheads, I always have.”

In Sussex, does he move in aristocratic circles, with “old money”? “A little bit. I’m very private. I go out to dinner most nights when I’m in London, but when I’m in the country I like to stay in. I certainly know about country living and about town living. My music is very urban, I think. It’s always been about cities, people. My mother was very urban, my dad was very rural, and so I have a foot in both camps.”

He regrets that his parents weren’t around long enough to give his own children “the odd clip round the ear”. And he wishes his boys had worked in a factory at some point. What would they have gained? “Discipline maybe. Just the grind of it and knowing every day isn’t great, you know, that you can’t have what you want all the time. Just common sense, but they’ve learnt in other ways.”

Ferry is proud of his eldest son Otis’s progress “in his hunting world” – he’s a joint master of the Shropshire Hunt. It was Otis who in 2005 burst into the House of Commons to protest at the ban on hunting and received a jail sentence. How did it feel when his son was… “Locked up?” He finishes my question. “Very, very bad indeed, yeah, but I don’t like dwelling on it.”

Ferry’s father Fred, he says, was “very quiet, smoked a pipe, courted my mother for 10 years, walked the five miles through the fields to see her and go back again because he had to be up to milk the cows. He was essentially a farm labourer, a ploughman, with the horses. He was very proud of his medals for winning all these ploughing contests. They were opposites in a way, because my mother was very tuned in to the modern world.

“My mother would do all the organising, deal with the pocket money. As long as he had money for his tobacco and his racing pigeons he was fine. So he’d give her his 15 quid and get a pound back and that would last him the week, because he never drank. He would have one drink maybe on pigeon day. It was frugal beyond belief.”

How was it even possible to dream of an existence like his? “I didn’t think I was better than anyone,” he says, “but I didn’t want to be kept down. I didn’t want to work in the mine or the local steel factory, which were the two main sources of work in the area that I lived in.”

Ferry spent his holidays working in the factory, on building sites, then a tailor’s shop. All the while he wanted to be an artist, which then “kind of veered into music”. Encouraging him along the way were his primary school teacher – “dear Miss Swaddle” – who fed his imagination in a class of 50; teachers at his grammar school after he passed the 11-plus; the uncle he talked into taking him to see concerts when he was too young to go by himself (“Chris Barber, Count Basie and Dizzy Gillespie, Ella Fitzgerald – whoever passed through Newcastle I’d try to save up to see them”); and then when he went to Newcastle University to study art, there was his lecturer, the artist Richard Hamilton, who once described Ferry as “my greatest creation”.

Bryan Ferry with Roxy Music, circa 1972 (Rex Features)

Ferry continued to dream of being an artist and had moved to London to work as a ceramics teacher when he put together the fledgling Roxy Music. We talk about how the internet age has sparked renewed interest in rock’s most iconic figures, and many a high-profile reunion. Does Ferry feel that route is blocked to him, because of the tensions that forced the classic Roxy line-up apart? This is an oblique approach. I want to ask him about Brian Eno, who added the synthesised sounds that took Ferry’s classic songwriting into the art-rock beyond on Roxy’s first two albums. It’s no secret that Eno left Roxy Music in the summer of 1973 because of “musical differences” with Ferry. “I don’t want to damage Roxy [by talking about it],” Eno said at the time. “I mean, I really like the other members, and I (pause) really like Bryan in a funny way.”

Ferry leans forward. I can tell I’ve touched a nerve. “What would block it?”

There’s no turning back. There remains a perception that his relationship with Brian Eno, although cordial, means that they couldn’t work together again. Does that block it?

“Well, you know, Eno played on the first two albums but we did have a few albums after that and another eight years of our career. So it’s not just him and me, there are others, and we did get together again in 2001. We hadn’t played together in 18 years and we did a reunion tour. You didn’t see that one, then?”

Now I can tell he’s cross. No, I didn’t see it. “We played all round the world, it went incredibly well but it didn’t make me really want to go and record a group album again. It’s not that odd, though. Because it doesn’t seem natural to work with the same people for the whole of your life.”

“I’ve worked with Brian in the studio a couple of times since and that was really refreshing, but I wouldn’t want to work with him for a long period of time. We get on very well when we’re alone, it’s when other people start coming in with expectations and saying, part of you is missing…”

Ferry has continued to collaborate with others, he points out, noting that Nile Rodgers, who provides the guitar on Daft Punk’s recent number-one, Get Lucky, has played on all his solo albums since 1985. Of course, Eno, too, went on to collaborate extensively, including with Ferry’s equally enduring glam-rock rival David Bowie. I wonder if Ferry has been to the Bowie show at the V&A, just a couple of miles down the road from his west London studio. “I’m aware of it. I haven’t been, have you? I ought to go before it closes, actually.”

Like Bowie, Ferry grew up to be one of the iconic figures of his generation. He became one of the stars he idolised and dreamt of being. Is he ever surprised that he became one of those people, a Marilyn Monroe? “I always tell myself that the people I did idolise were just people,” he says. “Marilyn was a goddess of the screen, yet she’s just a poor lonely girl at the end of the day, sad. Even the Sun King, Louis XIV, he was just a guy. I don’t wake up in the morning and think I’m an icon or something, that’s kind of weird. I like going to work every day and trying to achieve something.” And with that Ferry has to leave for Cannes, where he’s performing at a party for The Great Gatsby. In my imagination, he arrives by seaplane, in glorious Technicolor.

The above “Telegraph” article can also be accessed online here.

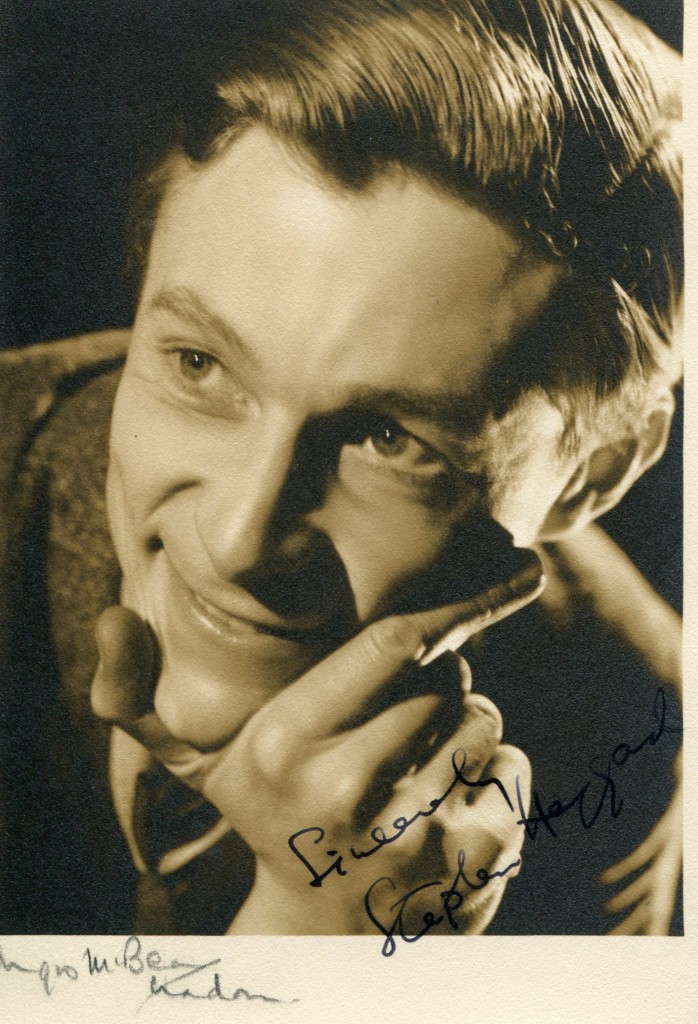

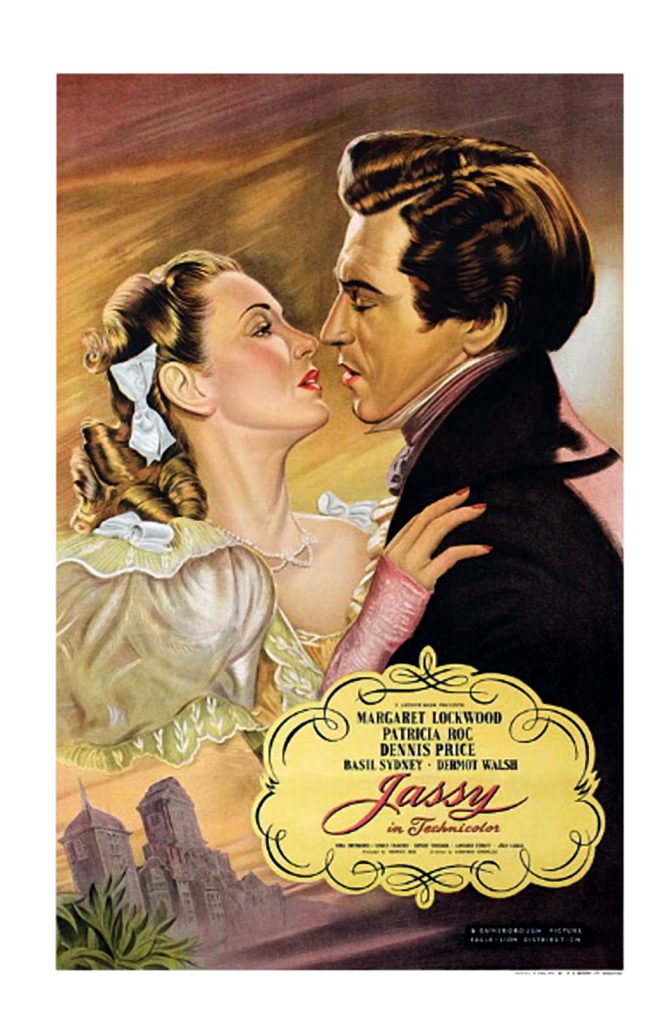

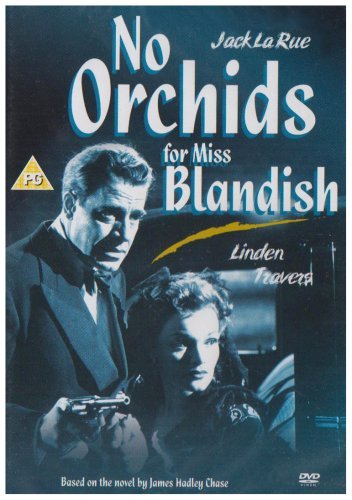

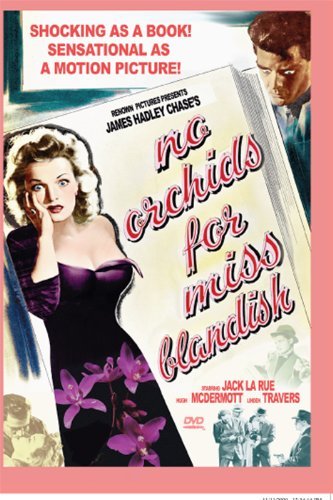

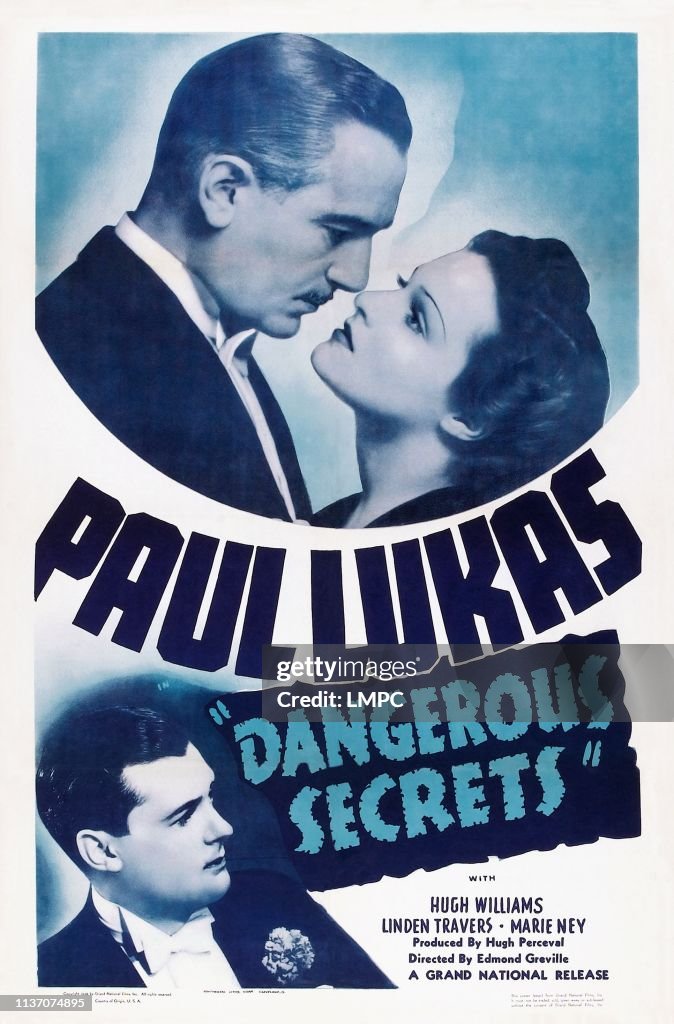

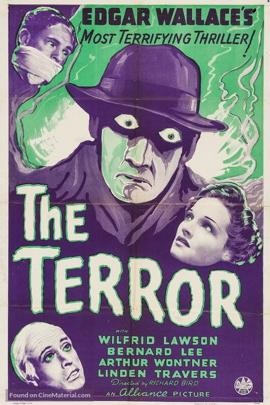

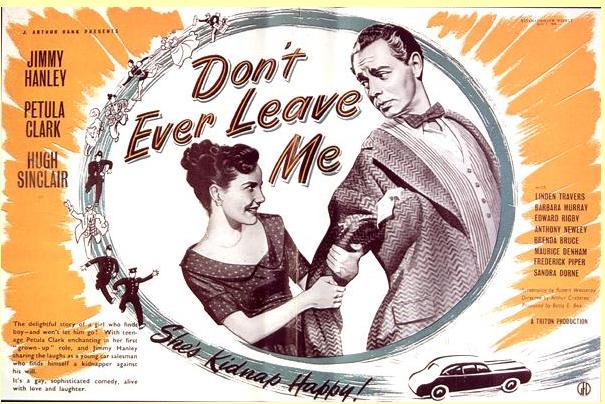

Linden Travers was a very attractive actress in British movies of the 1930’s and 40’s. She was the older sister of actor Bill Travers. She is particularly remembered for Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Lady Vanishes” in 1938 and then ten years later in “No Orchids for Miss Blandish” opposite George Raft. She died in Cornwall in 2001. She was the mother of actress Susan Travers.

Ronald Bergan’s “Guardian” obituary:

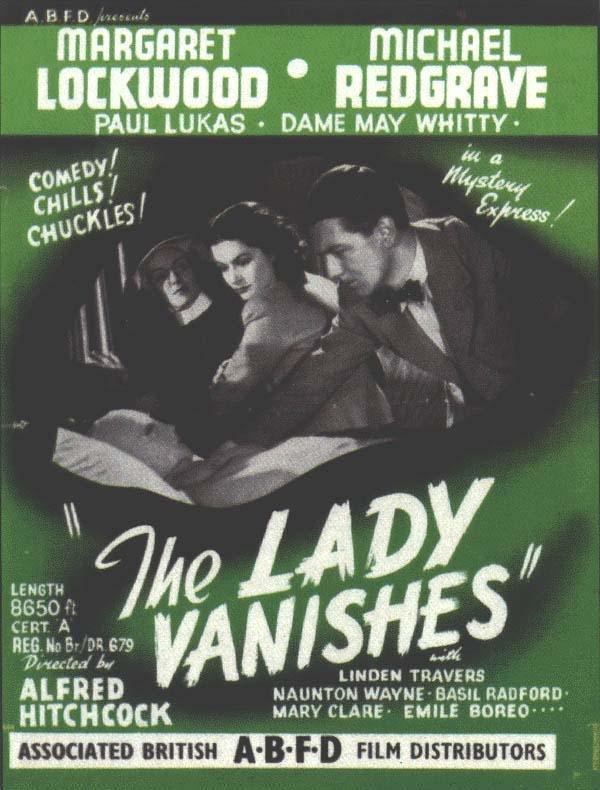

Among the many questions film-goers ask themselves while watching Alfred Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes (1939), the penultimate film of the director’s British period, is what on earth the exquisite brunette Mrs Todhunter sees in the pompous and pusillanimous Mr Todhunter (portrayed by portly Cecil Parker).

So passionate and sympathetic is the lovely Linden Travers, who has died aged 88, that we can only be pleased for her when Todhunter is shot by the Nazis as he tries to make a run for it. Travers’ performance in the Hitchcock picture, the best and most famous of her films, makes one wonder why she was not, at least, the equal of Margaret Lockwood, another “wicked lady” of British cinema. Perhaps she was a victim of the timidity of the British film industry in the 1930s and 40s.

The Lady Vanishes was Travers’ 10th feature, but her own favourite was No Orchids For Miss Blandish (1948), in which she played the title role, repeating her stage performance of six years earlier in London. The British film, directed by St John L Clowes, based on the James Hadley Chase shocker, was considered such strong stuff – “the most sickening exhibition of brutality, perversion, sex and sadism ever to be shown on a cinema screen,” screamed the Monthly Film Bulletin – that it was banned in England for many years. Despite most of the British cast struggling to convince as New York gangsters using unspeakable dialogue, Travers, as the sensual kidnapped heiress who falls for her psychotic captor, emerged with some credit.

She was born Florence Lindon Travers in Durham, and showed her talents at an early age. While still a pupil at the Convent de la Sagesse, she was engaged to teach younger classmates elocution, drama, painting and sketching. Her first professional stage appearances were in repertory at the Playhouse, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, in 1933.

The following year, she played the ingénue lead in Ivor Novello’s Murder In Mayfair, at the Globe in London. There, she met her future first husband, Guy Leon, whose sister was in the cast. (Their daughter, Jennifer Susan, was born in 1939.) Travers was soon alternating between stage and screen, and between femme fatale roles and light comedies.

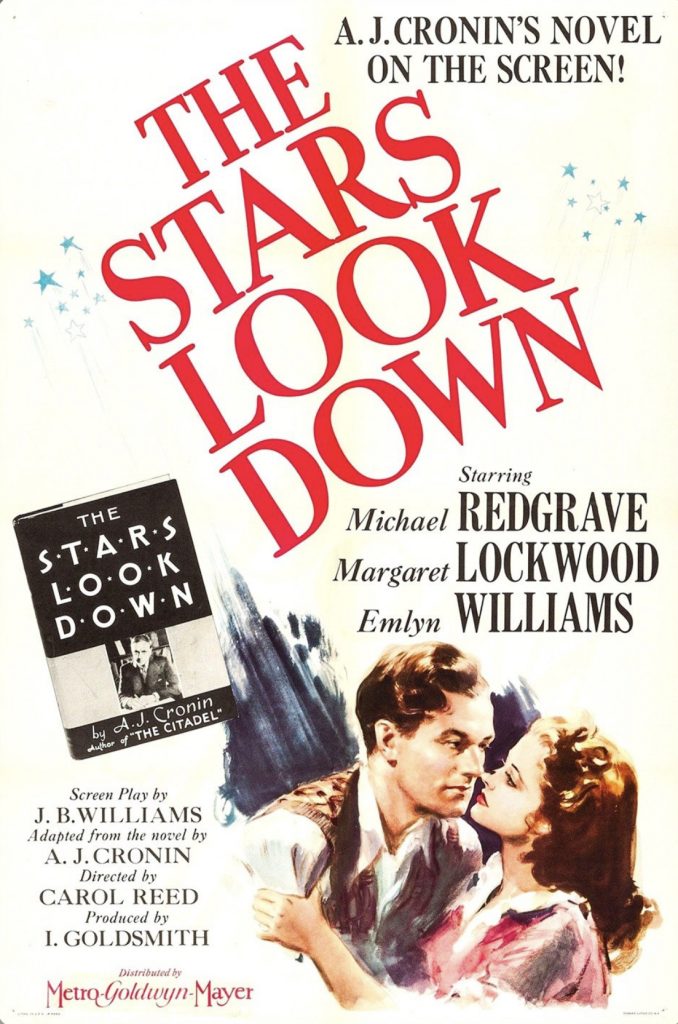

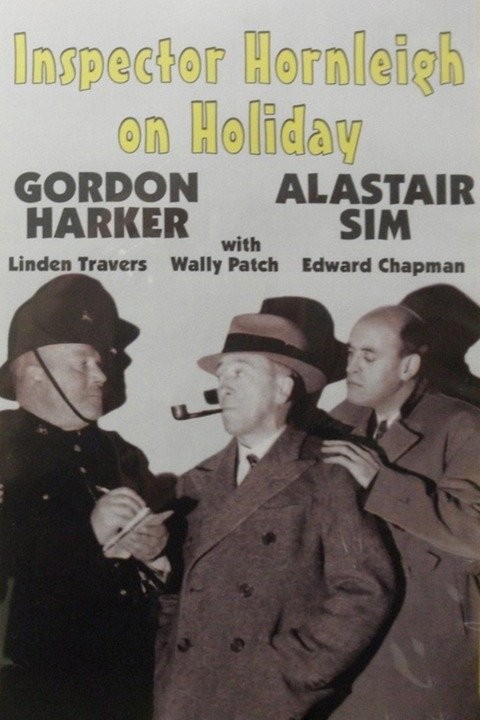

Carol Reed cast her in small, but sexy, parts in Bank Holiday (1938) and The Stars Look Down (1939), both starring Margaret Lockwood. Then, “I seem to have jumped out of being mistresses to playing with the comics,” she recalled later. She was an effective foil to Tommy Trinder in Almost A Honeymoon (1938), was withering towards Arthur Askey in The Ghost Train (1941) and was George Formby’s inamorata in South American George (1941).

In the latter, she is a press agent who talks posh, like all Formby’s leading ladies, though she drops into Lancashire dialect once or twice, much to George’s delight.

Travers again played second fiddle to Margaret Lockwood in Jassy (1947), and was Augusta Leigh, one of the many female witnesses in The Bad Lord Byron (1949) accusing poet Dennis Price of caddishness. Her last feature was Christopher Columbus (1949), in which she is chased around the Spanish court by King Ferdinand.

After her second marriage to James Holman in 1948, and the birth of their daughter, Sally Linden, the following year, Travers limited herself to occasional television appearances, allowing her much younger brother, Bill Travers, to continue the family acting tradition. She had, however, always continued painting and, with her sisters, Alice and Pearl, opened the Travers Art Gallery in Kensington in 1969.

In 1974, after her husband died of a heart attack, Travers spent some years travelling, before settling down to paint in St Ives, in Cornwall. She also studied psychotherapy, and qualified as a hypnotist. In the 1990s, she appeared at a showing of The Lady Vanishes at the National Film Theatre, and was seen in a BBC tribute to Alfred Hitchcock, instantly recognisable as the shamefully underused star of British pictures.

She is survived by her two daughters, her brother Ken and her sister-in-law, Virginia McKenna.

· Florence Lindon ‘Linden’ Travers, actor, born May 27 1913; died October 23 2001

Benedict Taylor was born in 1960 in London. He is the eldest of six children. He lived in Nigeria for the first few years of his life. He made his debut in “The Turn of the Screw” on television in 1974. His movies include “The Watcher in the Woods” with Bette Davis and Carroll Baker, “Every Time We Say Goodbye” with Tom Hanks and “Monk Dawson” with John Michie.

Jeremy Northam was born in 1961 in Cambridge. He made his U.S. movie debut opposite

Sandra Bullock in “The Net”. His other films include “Carrington” and “Gosford Park” where he played ‘Ivor Novello’.

TCM overview:

Tall and slender with dark good looks and a rich, plummy voice, Jeremy Northam was already established as a stage and television performer in his native Britain when he landed his breakthrough screen role as the suavely seductive villain stalking Sandra Bullock in the cyber thriller “The Net” (1995). The son of a professor and a potter, he spent his formative years in Bristol and Cambridge. After completing his college education, Northam enrolled at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School but left before completing the three-year program when he began landing TV roles like the soldier in the WWI drama “Journey’s End” (1988). The following year, the limelight shone on him briefly when he understudied and then replaced Daniel Day-Lewis in the National Theatre production of “Hamlet”. Additional stage roles followed, including an award-winning turn in “The Voysey Inheritance” and a supporting role in “The Gift of the Gorgon” (1992), starring married couple Judi Dench and Michael Williams as well as additional work at the Royal Shakespeare Festival. As his stage presence increased, Northam lent his presence to other small screen roles before landing his first major feature role, as Hindley Earnshaw in the uneven remake of “Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights” (1992). That film met with a derisive critical reaction in England and was relegated to TV in America (it aired on TNT in 1994).

After his strong performance in “The Net”, Northam seemed on the verge of being typecast as cads when he portrayed Beacus Penrose who beds and abandons the titular artist played by Emma Thompson in the biopic “Carrington” (1995). Switching gears, however, he excelled in the real-life role of a man with dual personalities, the reclusive composer Peter Warlock and his bete noir, the dyspeptic music critic Philip Heseltine in “Voices/Voices From a Locked Room” (also 1995). Further demonstrating his range, Northam cut a dashing romantic figure as Mr. Knightly to Gwyneth Paltrow’s “Emma” (1996) before stumbling a bit in both “Mimic” (1997), as a scientist, and Sidney Lumet’s remake of “Gloria” (1999), as a gangster. While his onscreen roles offered little challenges to the actor, he found success as a buttoned-up real estate agent who falls in with some free spirits in the British telefilm “The Tribe” (1998) and in his return to the London stage playing a gay obstetrician in “Certain Young Men” (1999). In fact, 1999 would prove to be a key year for the actor, with high profile, critically-praised performances in three films. The Sundance favorite “Happy, Texas” cast him opposite Steve Zahn as a pair of escaped convicts who seek refuge in the titular town where they are mistaken for a gay couple. In David Mamet’s remake of “The Winslow Boy”, Northam anchored the film as the wily barrister defending the boy accused of theft who also harbored unexpressed romantic yearnings for the Winslow daughter (Rebecca Pidgeon). Rounding out the trio of movies was Oliver Parker’s period adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s “An Ideal Husband”, with the actor as a married politician who is haunted by a youthful indiscretion. Continuing to corner the market in period films, Northam joined the cast of the Merchant Ivory production “The Golden Bowl” (2000), playing an Italian prince. He followed up with a fine turn as actor-composer Ivor Novello in the Robert Altman-directed period mystery “Gosford Park” (2001) and as an 19th-century poet in Neil LaBute’s adapation of A S Byatt’s novel “Possession” (2002). After a much discussed stint playing Dean Martin opposite Sean Hayes as Jerry Lewis in the CBS biopic “Martin & Lewis” (2002) in which Northam ably captured the singer-actor’s suave charisma if not his naughty-boy appeal, Notham appeared in the Mel Gibson-produced adaptation of “The Singing Detective” (2003) and played a French army officer hounding Michael Caine in “The Statement” (2003). He next played Walter Hagen in the biopic “Bobby Jones, Stroke of Genius” (2004), which told the story of the iconic golf champion (Jim Caviezel) who quit the sport on top at age 28.

The above TCM overview can be accessed online here.

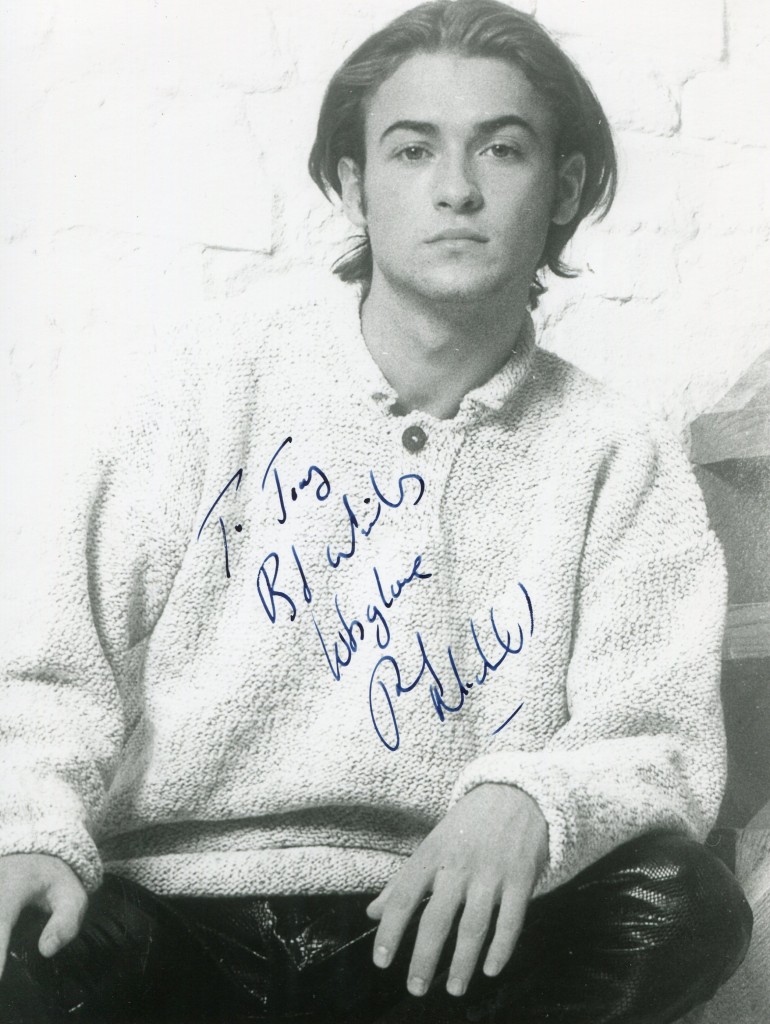

Paul Nicholls was born in 1979 in Bolton, Lancashire. His movies include “The Trench”, “The Clandestine Bridge. He was seen in “Law & Order UK up to this year.

IMDB entry:

Born to a roofer and a psychiatric nurse, Paul was born on April 12, 1979, joining his sister, Kelly who was born in 1978. Paul started acting at an early age of 10, when he joined the Oldham Theatre Workshop, but had acted before that at Church Road Primary School, Bolton and then Smithhills Dean High School. Still at the age of 10, Paul had his first television role, in “Childrens Ward” on ITV, though only saying 3 lines.

Later, he started appearing in TV shows like The Biz (1995) and became UK teenage girls’ favourite pin-up when he joined the EastEnders (1985) cast as Joe Wicks. 12 record companies have reportedly offered Paul the opportunity to record a single but they have all been turned down. Paul has publicly stated that he will never record a single, adding that his cat, Gizmo, is better at singing than him.

David Tennant was born in 1971 in West Lothian, Scotland. He is best known for his performance as “Dr Who”. He also played ‘Barty Crouch Jnr’ in “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire” in 2005. His other movies include “The Decoy Bride”.

TCM overview:

To much of the world’s television viewing audience, David Tennant was the tenth and arguably most popular incarnation of England’s iconic science fiction hero “Doctor Who” (BBC One 1963-1989, 2005- ), who took audiences by storm with the venerable science fiction television series’ revival in 2005. But the Scottish actor’s c.v. also included a lengthy, award-winning string of performances in classical and modern theater as well as numerous turns in British television dramas and comedies. But it was his vigorous and frequently amusing turn as the Doctor that not only restored much of the charm and appeal of the long-running series, which had been mothballed for nearly two decades prior to 2005, but also vaulted him to international fame. Unlike many of the other actors who played the Doctor during its five decade run, Tennant was successful in finding substantive work outside of the show, including appearances in “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire” (2005) and such highly praised small screen efforts as “Recovery” (BBC One 2007) and “Broadchurch” (ITV 2013- ).

Born David John McDonald on April 18, 1971 in the Scottish town of Bathgate, David Tennant was the son of a Presbyterian minister, the Reverend Alexander McDonald, and Essdale Helen McLeod, whose father, Archibald McLeod, was a champion footballer for Scotland in the 1930s. His fascination for acting developed at a very early age and was inspired in part by “Doctor Who,” of which he was a devoted fan. Tennant began acting in school productions during his time in primary and secondary schools, and soon added Saturday classes at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama to his training. He was admitted to the Academy at the age of 16, the same year he made his screen debut in an anti-smoking film produced by the Glasgow Health Board. At his time, he adopted the stage name of “David Tennant,” inspired by Pet Shop Boys singer Neil Tennant, because an actor named David McDonald was already registered with the Equity union. He graduated from the Academy with a Bachelor of Arts in acting and landed his first professional role in a production of Bertolt Brecht’s “The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui” for the agitprop 7:84 Theatre Company. Roles on television soon followed, most notably his 1993 turn as a transsexual barmaid well loved by the patrons of her pub on the comedy “Rab C. Nesbitt” (BBC Two 1988-1999, 2008- ). The following year, Tennant earned his breakthrough role as a young bipolar patient/DJ at a hospital radio station on “Takin’ Over the Asylum” (BBC Scotland 1994).

A critically acclaimed appearance in a 1995 production of Joe Orton’s “What the Butler Saw” at the Royal National Theater in London underscored Tennant’s growing reputation as a stage star on the rise, which he soon cemented by joining the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1996. By 2003, he had netted Olivier and Ian Charleson Award nominations for performances in “The Comedy of Errors” and Kenneth Lonergan’s “Lobby Hero,” which translated into regular work as a guest star on episodic television. These efforts included appearances on the revived “Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased)” (BBC One 2000-2001) and the well-praised television version of “People Like Us (BBC Two 1999-2000). In 2004 and 2005, Tennant received critical praise for his comic performances in the BBC’s adaptation of Anthony Trollope’s “He Knew He Was Right” (2004) and the musical series “Blackpool” (BBC One 2004), as well as supporting turns in more dramatic fare like the live broadcast of “The Quatermass Experiment” (BBC Four 2005) and in “Casanova” (BBC Three 2005) as the legendary lover in his younger days. The last production was written by Russell T. Davies, who cast Tennant as the tenth incarnation of the Time Lord in his revival of “Doctor Who” that same year.

Tennant replaced Christopher Eccleston as The Doctor in the second season of the new “Doctor Who” and quickly became one of the most popular actors to personify the role in the course of its five-decade history. His Doctor combined the whimsy and eccentricity of Tom Baker’s Fourth Doctor with flashes of the steely reserve seen in Jon Pertwee’s Third Doctor, but was also shot through with streaks of loneliness and romantic longing that made him positively Byronic at times. Tennant was also a devotee of the series, which imbued both his performance and his promotional appearances outside the show with an infective enthusiasm that won him numerous fans. He participated in numerous related and spin-off projects, from audio plays by Big Finish Productions to the BBC’s charity holiday specials and “The Sarah Jane Adventures” (CBBC 2007-2011), which starred former Baker companion Elisabeth Sladen reprising her turn as the intrepid Sarah Jane Smith. For his performances on “Doctor Who,” Tennant won three National Television Awards and a BAFTA Cyrmu (BAFTA in Wales), but more importantly, his performance was crucial in reviving a moribund franchise and making it relevant to modern audiences. Fans would later name him the best Doctor in the history of the series by its official house organ, Doctor Who Magazine.

While appearing as the Doctor, Tennant also remained busy with numerous other projects, most notably as the villainous Barty Crouch, Jr. in “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire” (2005) and a 2005 production of “Look Back in Anger.” In 2008, he won rave reviews for his performance as Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” for the Royal Shakespeare Company, which was subsequently filmed as a BBC Two production the following year; his work as a charming psychopath in “Secret Smile” (ITV 2005) and as a brain injury victim in “Recovery,” also drew critical acclaim. These, along with turns in numerous episodic television series, promotional appearances, recordings for audio books and radio plays and even television advertisements, made Tennant one of the busiest and most in-demand performers in the United Kingdom between 2005 and 2009. At the end of that four-year period, Tennant decided to part ways with the Doctor with a quartet of four special episodes, culminating in “The End of Time” (BBC One 2010), which was seen by over 10 million viewers. While his final episodes aired, Tennant filmed a pilot for an American series, “Rex is Not Your Lawyer” (NBC 2009), about a panic-stricken Chicago lawyer who coached his clients while representing themselves. Though it received considerable media attention, the pilot was not picked up for broadcast.

Tennant worked steadily in the post-Doctor years, picking up a Best Actor nomination from the Royal Television Society Programme Awards as a photographer raising five children after the death of his partner in “Single Father” (BBC One 2010) while enjoying critical praise for appearances in “United” (BBC Two 2011) and the semi-improvised “True Love” (BBC One 2012). His fame as the Doctor won him opportunities in the States, but these efforts, including a remake of the 1985 horror film “Fright Night” (2012) and an audition to play Hannibal Lecter in NBC’s “Hannibal” (2013- ), received either a lukewarm response or failed to come to fruition, save for his spirited vocal performance as Charles Darwin in the Aardman Animation film “The Pirates! Band of Misfits” (2012). The U.K. remained his most diverse showcase, as evidenced by his antagonistic police detective hunting a child murderer in “Broadchurch” and his gifted barrister in “The Escape Artist” (BBC One 2013). That same year, two different factors of Tennant’s vast fan base were thrilled to hear that 2013 would not only see the actor reprise the Doctor for “The Day of the Doctor” (BBC One, 2013), a 75-minute special celebrating the 50th anniversary of “Doctor Who” by teaming the Tenth Doctor with his successor, Eleventh Doctor Matt Smith, but also a return to the Royal Shakespeare Company in a production of “Richard II.” In 2014, Tennant made his debut on American TV by starring in “Gracepoint” (Fox 2014), a limited-run American adaptation of “Broadchurch,” which had garnered both strong ratings and solid reviews when it was broadcast on U.S. television in the summer of 2013.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

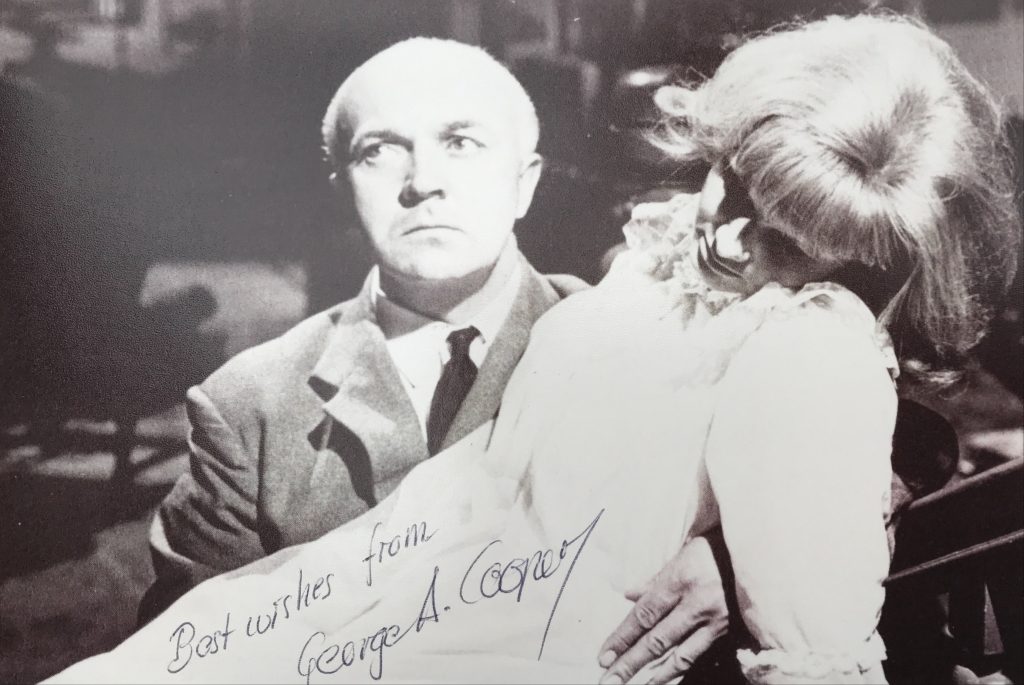

George A. Cooper is a very profilic British actor with a long list of credits on film and television. He was born in 1925 in Leeds. His movie debut was in 1946 in “Men of Two Worlds”. His movies include The Secret Place” in 1957, “Miracle in Soho” and “Violent Playground”. George A. Cooper died in 2018.

“Loose Cannon” page website:

George Cooper was born in Leeds in 1925, As a youth he decided he wanted to be an electrical engineer. He soon changed his mind and his next planned career was as an architect which also fell by the side as he realised his true yearning was to be an actor. However the war intervened and he was called up for National Service and became a Royal Artillery Surveyor, being posted in Dulally India where he became involved in the armies concert party.

After the war he joined the Theatre Workshop in Manchester run by Joan Littlewood where he stopped for almost 6 years whilst gradually moving into television and adding the “A” to his stage name due to confusion with another George Cooper.

During the 1960’s he become one of the most familiar character actors on television and his filmography includes almost all of the major shows of the day such as Coronation Street, The Adventures of Robin Hood, An Age of Kings, Danger Man, Z Cars, Softly Softly, The Avengers and Man in a Suitcase.

In the following decade he continued in the same stead but also managed to appear in many classic sitcoms such as Steptoe & Son, Bless this House, Rising Damp, Sykes and a well remembered role as the job advisor in Some Mothers Do ‘Ave ‘Em who attempted to get Frank Spencer employment, the only time in a TV studio George admits to having an attack of the giggles. He also starred in the TV adaptation of Billy Liar in which he had previously starred in the West End.

Once again in the 1980’s George was again very busy in serials such as Juliet Bravo, When The Boat Comes In, CATS Eyes and Taggart before settling down in the role he is probably best remembered as Mr Griffiths, caretaker of Grange Hill, where his experience helped many of the young child actors, much to George’s delight.

Now retired, George remains a very friendly man and enjoyed sharing his experiences with the Loose Cannon team on your behalf.

The above page on the “Loose Cannon” website can be accessed here.

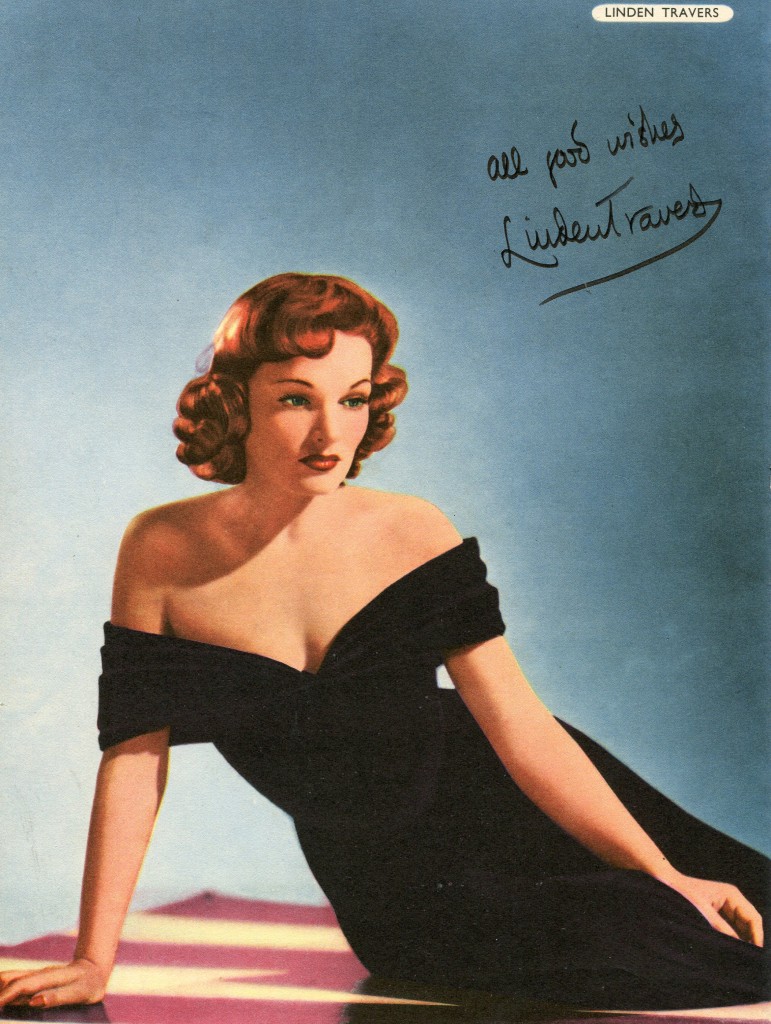

Anyone who knows me are aware that I am a bit of a movie buff. Over the past few years I have been collecting signed photographs of my favourite actors. Since I like movies so much there are many actors whose work I like.