Van Johnson was born in 1916 in Newport, Rhode Island. He started acting on Broadway in 1935. He was Gene Kelly’s understudy in the Broadway musical “Pal Joey”. He was first noticed on film in 1942 in “Murder in the Big House” with Faye Emerson. He replaced Lew Ayres in the Dr Kildare series. He won a contract with MGM and made such movies as “The Human Comedy”, “A Guy Named Joe”, “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo” and “Brigadoon”. In his later years he guest starred with June Allyson in Angela Lansbury’s “Murder She Wrote”. Van Johnson died in 2008 at the age of 92.

I”Guardian” obituary:

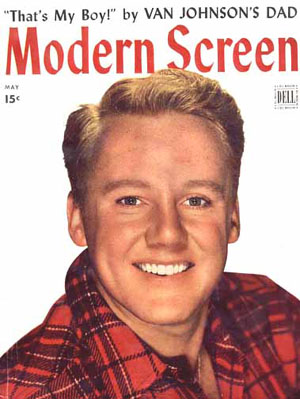

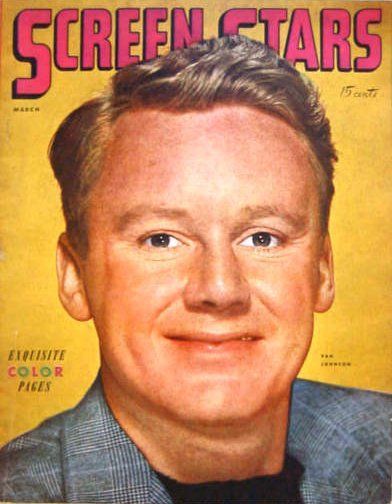

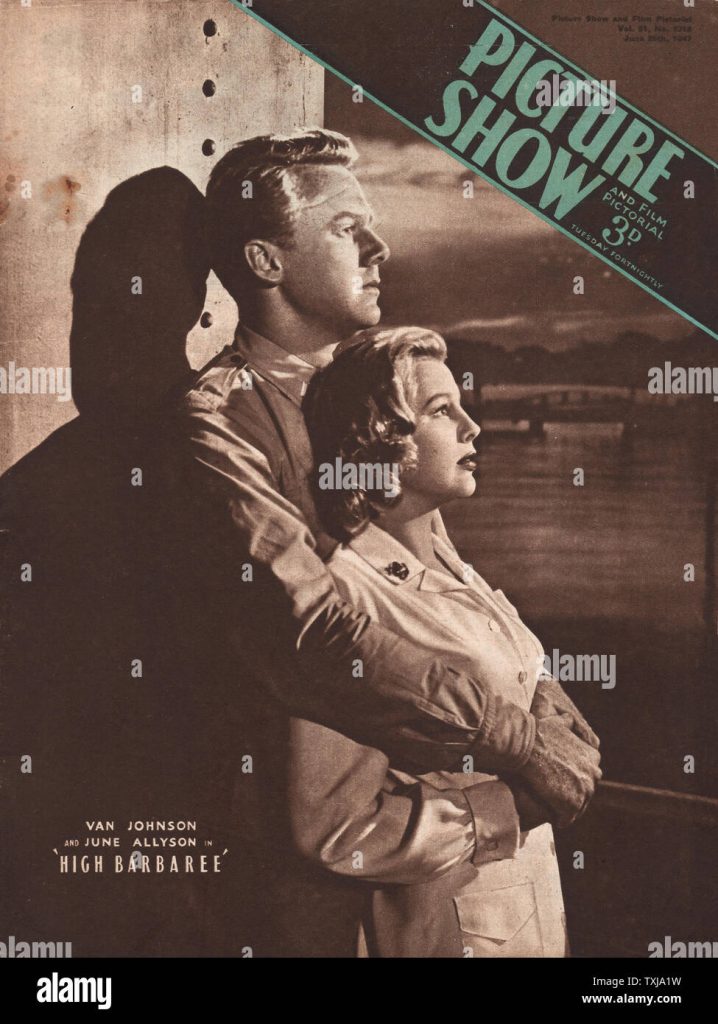

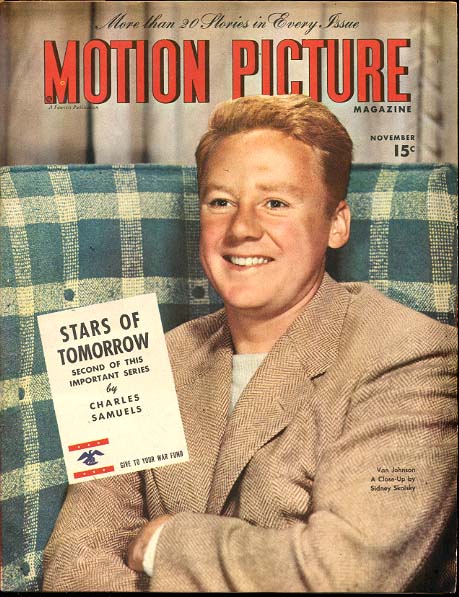

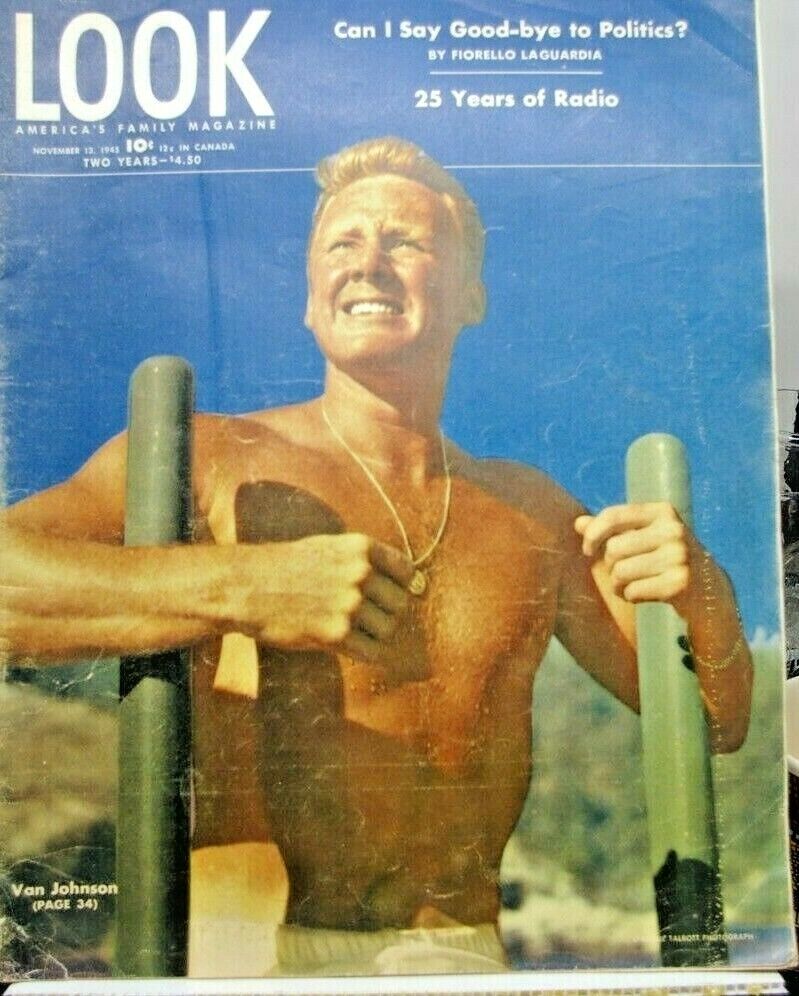

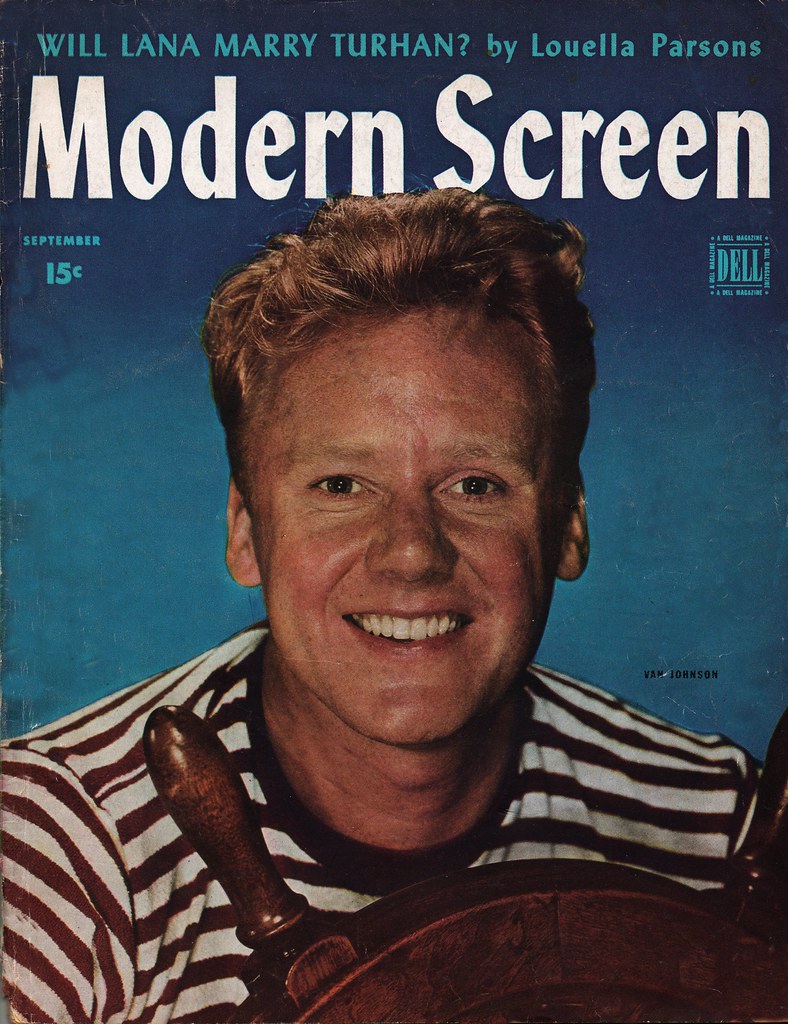

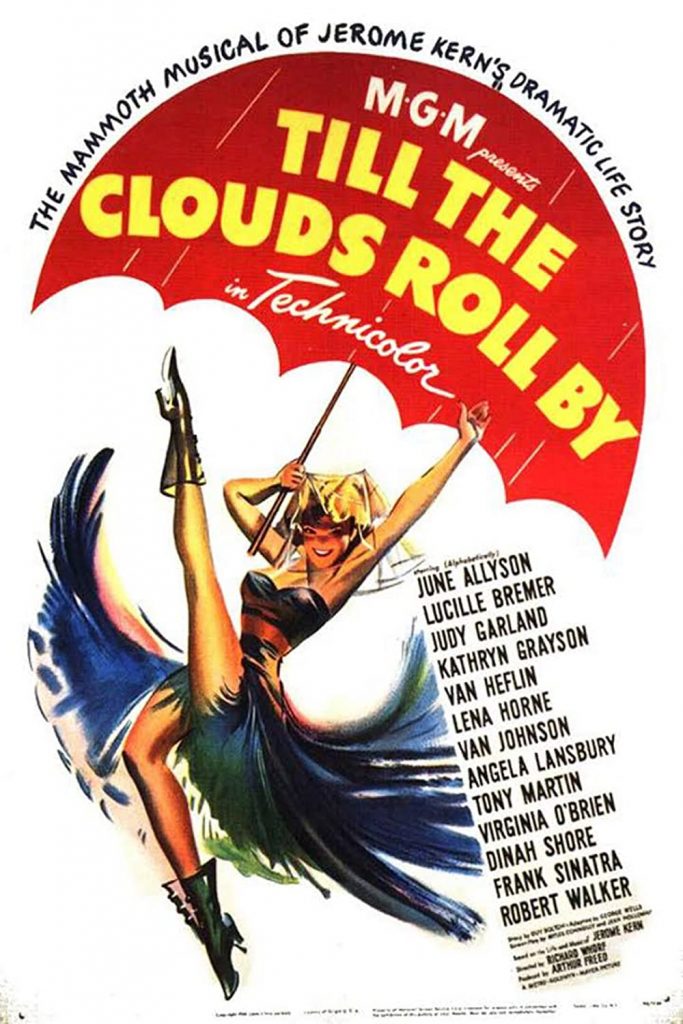

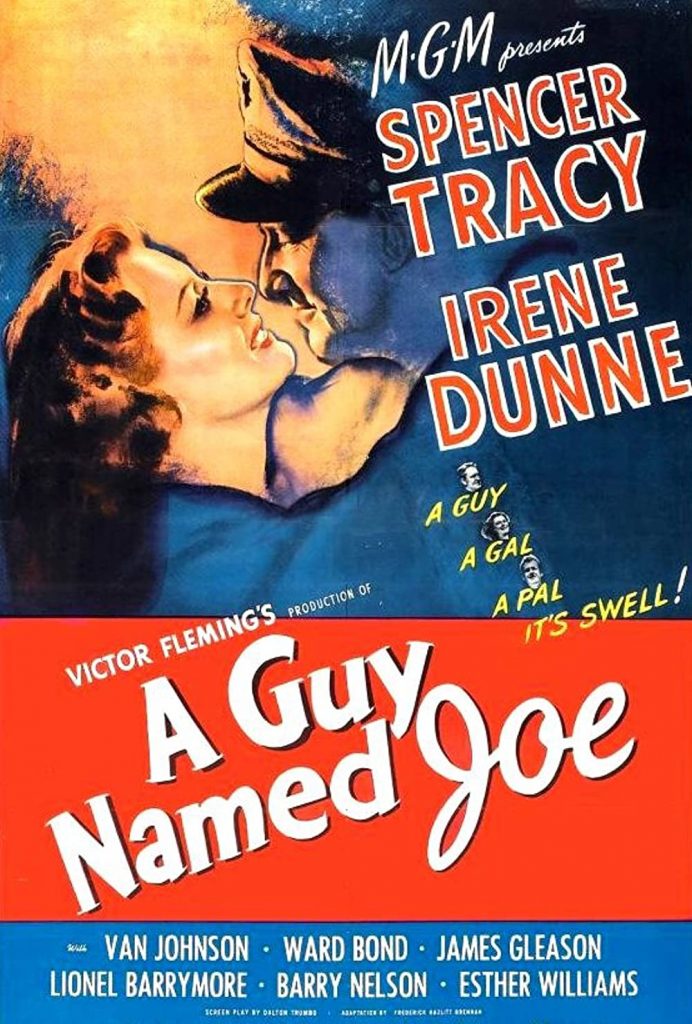

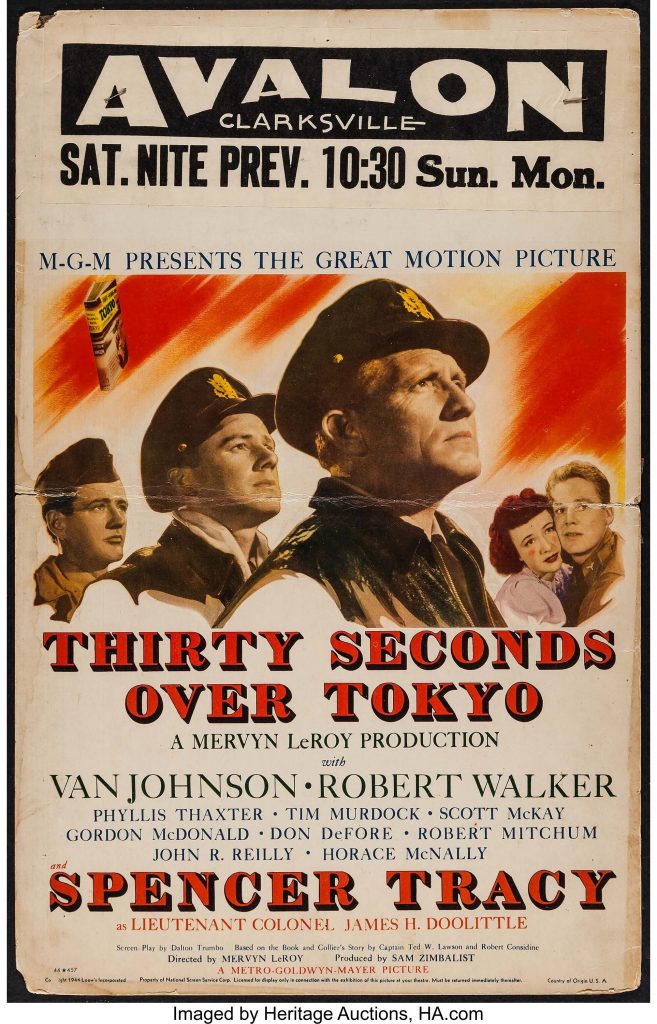

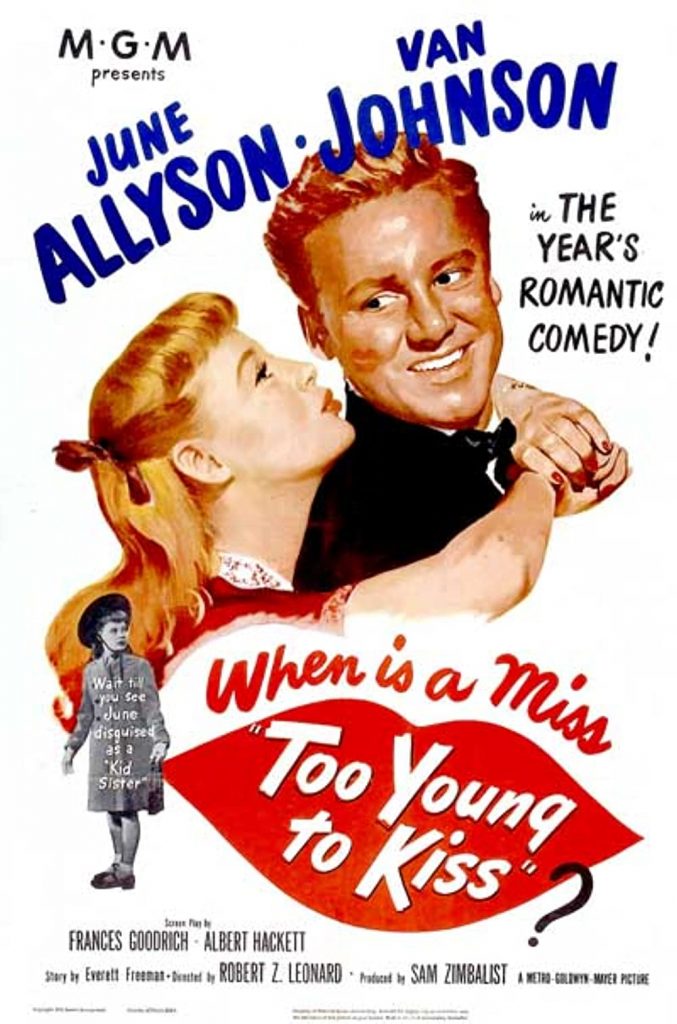

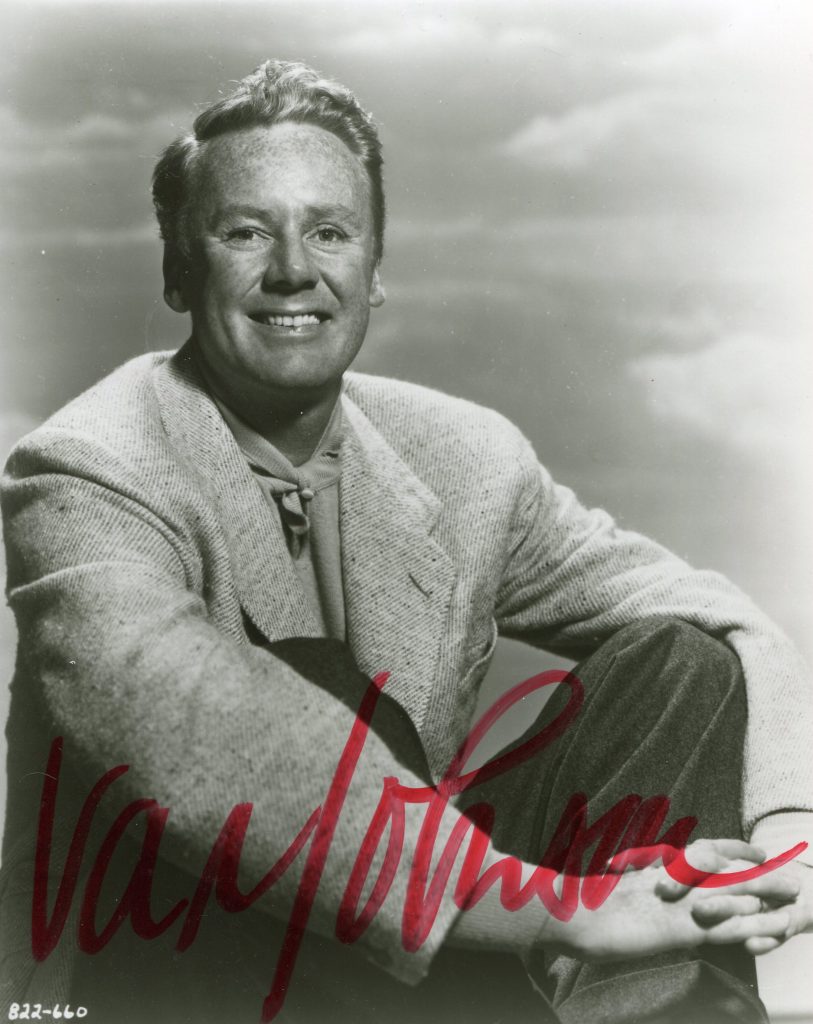

Recalling the life of Van Johnson, who has died aged 92, is not simply to remember a talented, once boyishly handsome film and stage star, but a golden era of Hollywood. A time when MGM could claim “more stars than there are in the heavens” and leading men fell into distinct types, of which Johnson’s freckle-faced boy-next-door was one. He also fell into another significant category, the MGM leading man, the guy who squired the gals. Leading ladies such as Elizabeth Taylor, June Allyson and Esther Williams were paired with him, as was Judy Garland and such male luminaries as Spencer Tracy, Clark Gable and Gene Kelly.

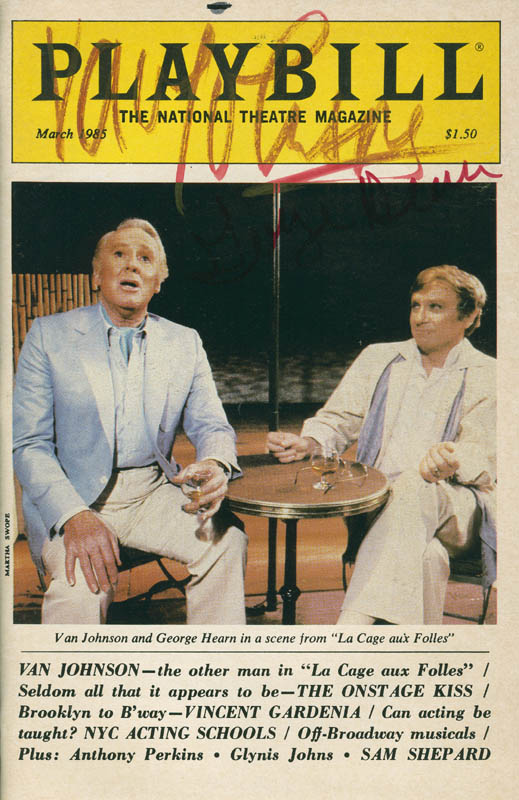

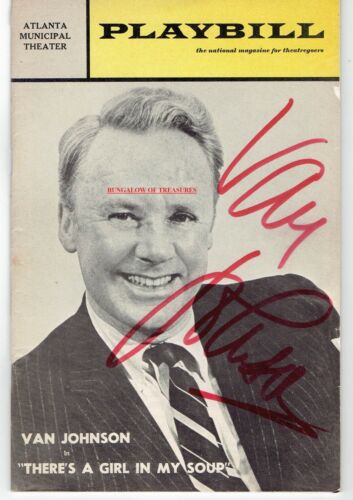

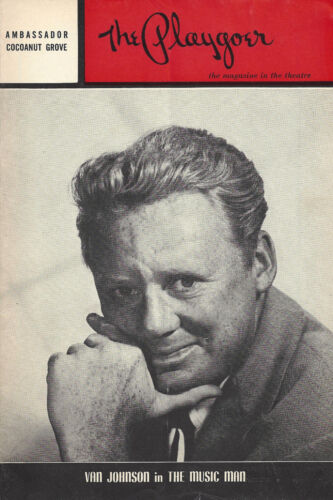

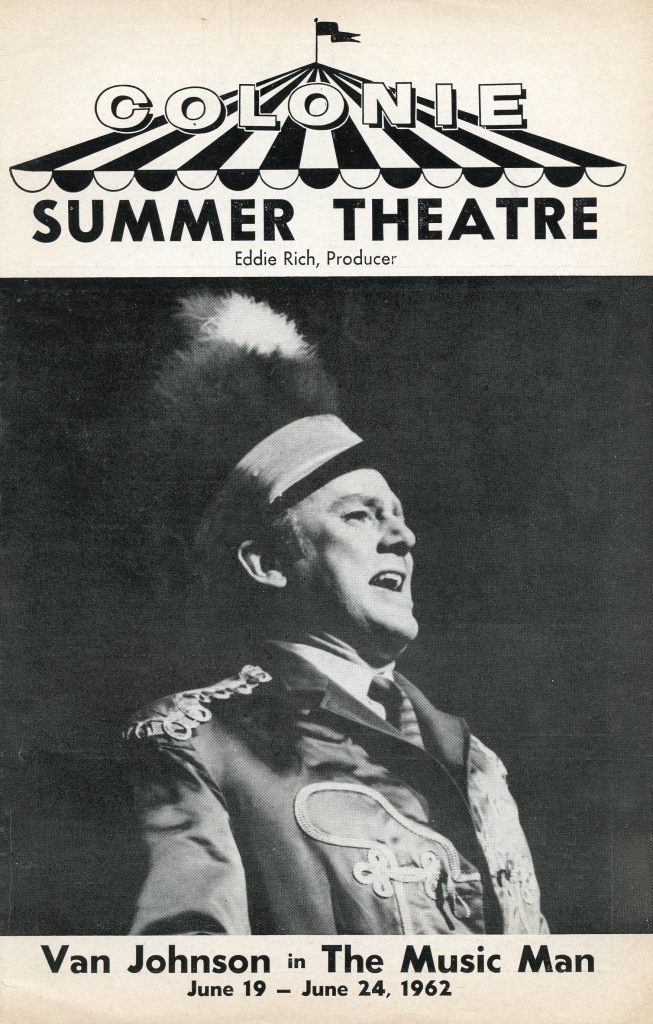

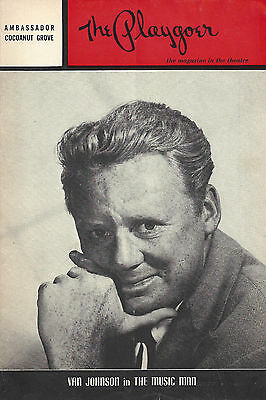

But that was then, and those heydays – in Johnson’s case from the early forties until the mid-fifties – are long gone. In the course of a dozen years he appeared in nearly 50 movies, out of the total of 80 that he notched up between 1942 and 1992. In addition to big screen roles, he starred in many television dramas and mini-series, and guested in such programmes as Batman and Murder, She Wrote. He often returned to the stage, where he began his career in New Faces of 1936, starring in such musicals as The Music Man (on tour and in London) and La Cage aux Folles.

Such a career would have seemed impossible to his resolutely non-showbusiness family. Charles Van Johnson was born in Newport, Rhode Island. His mother, an alcoholic, abandoned the family early on, and he was brought up by his austere Swedish-American father, also called Charles. Johnson’s stepson, Ned Wynn, wrote in his memoir, We Will Always Live in Beverly Hills, that when Johnson became a star he invited his father to Los Angeles and took him to the famous Chasen’s restaurant, only for Charles Johnson to refuse to eat anything but a tuna sandwich. “Van was devastated,” Wynn wrote. “He had wanted to show his father that now, after years of a grey, loveless, miserly life, he was a star, he could afford steak. And the old bastard had beaten him down one more time.”

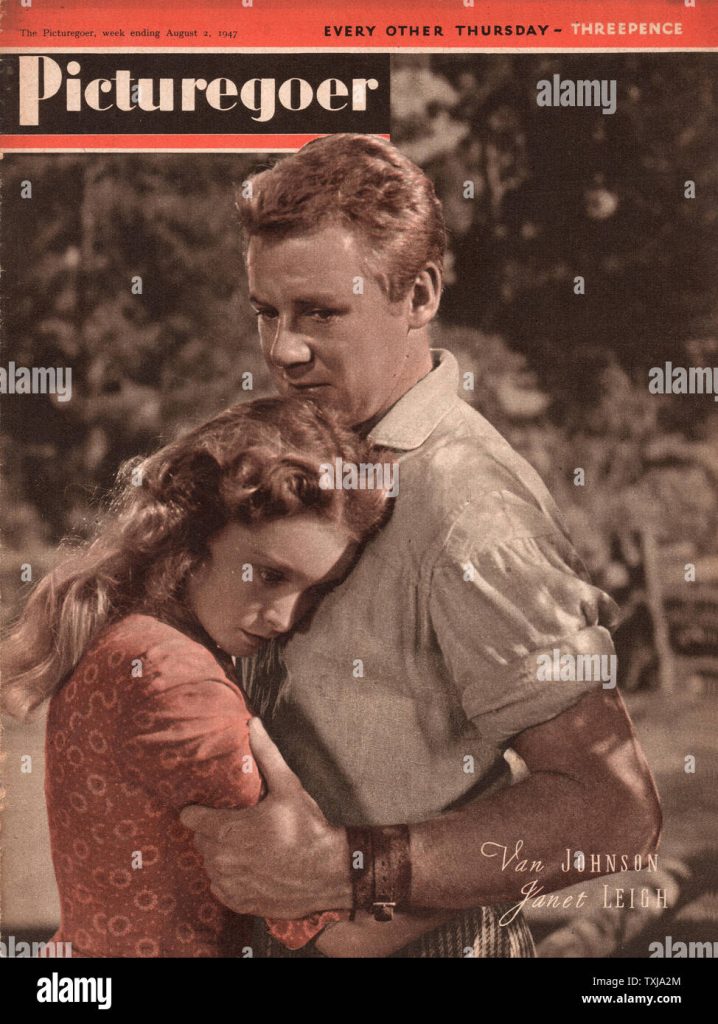

Johnson moved to New York after finishing high school in 1935. The engaging young man with a bright smile and sandy hair took dancing and singing lessons and began work in the chorus. In 1939 he landed a small part in Pal Joey while understudying the star, Kelly. Just 15 years later, he shared top billing with Kelly in the film version of Brigadoon.

After such useful training, he headed west, making an uncredited debut in Too Many Girls (1940) and securing a contract with Warner Bros. When that lapsed, he was taken up by MGM and became a contract player, joining the illustrious group who made up the largest and most famous group of entertainers ever controlled by one organisation. In an interview in 1985, he recalled his years at MGM with fondness. “It was one big happy family and a little kingdom,” he said. “Everything was provided for us, from singing lessons to barbells. All we had to do was inhale, exhale and be charming. I used to dread leaving the studio to go out into the real world, because to me the studio was the real world.”

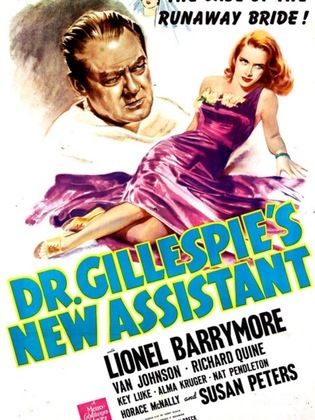

Johnson got a lucky break with Dr Gillespie’s New Assistant (1942) where he played the role vacated by Lew Ayres (whose objection to the war made him unemployable in Hollywood for many years). So popular was Johnson that by his third appearance as the assistant he had taken over as star. The following year, Johnson played a pilot guarded over by an angel (Tracy) in A Guy Named Joe, one of the 20 or so films that made him a bobby soxers’ delight. While filming it, however, he had a near-fatal car crash that made him unfit for military service. Helped by the comparative lack of competition – Robert Taylor, James Stewart and Gable had all joined the armed services – he soon became a leading man. In 1944, he received his first top billing in Two Girls and the Sailor. Two years later Johnson entered the list of Hollywood’s top 10 stars, fourth only to Greer Garson, Bing Crosby and Ingrid Bergman. He was among the all-star cast in the glossy Week-End at the Waldorf (1945), and the dry leading man in two Williams extravaganzas, The Thrill of Romance (1945) and Easy to Wed (1946). By the war’s end he was an established star.

In 1948 he displayed increasing versatility by starring in a sturdy war film, Command Decision, switching to a frothy romance, The Bride Goes Wild, opposite Allyson, and then joining his friend Tracy – and Katharine Hepburn – in Frank Capra’s political satire State of the Union. This sharp movie gave him one of his best parts, and he followed it in 1949 with the engaging In the Good Old Summertime, MGM’s musical reworking (for Garland) of the classic The Shop Around the Corner.

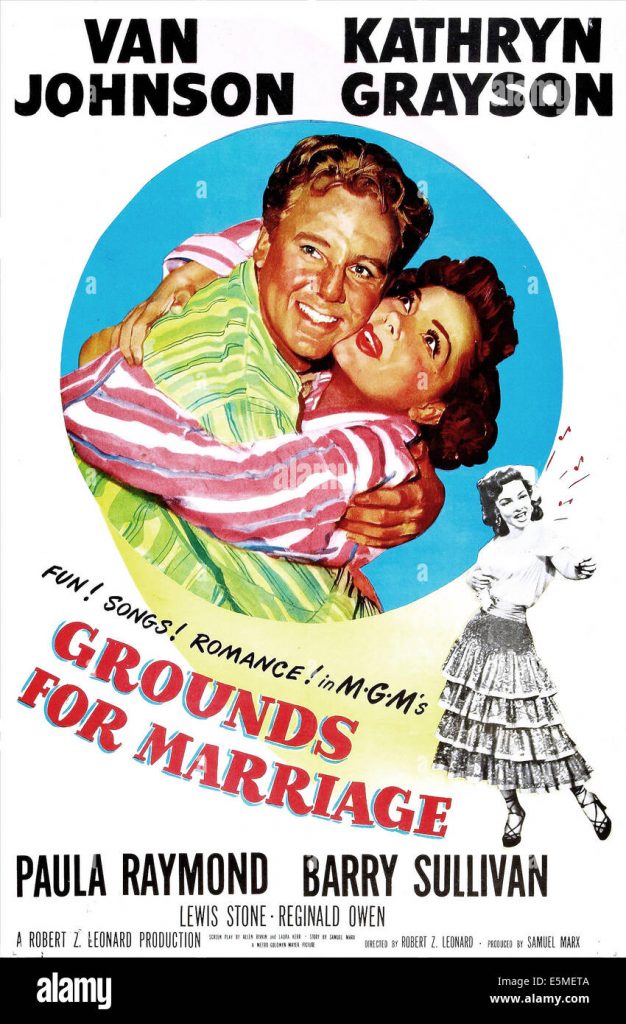

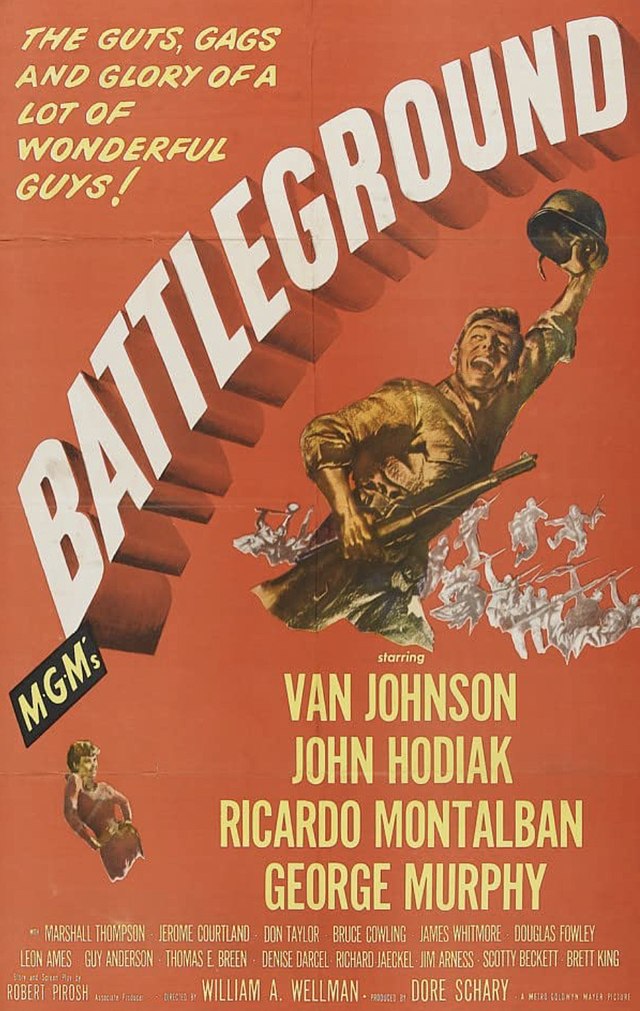

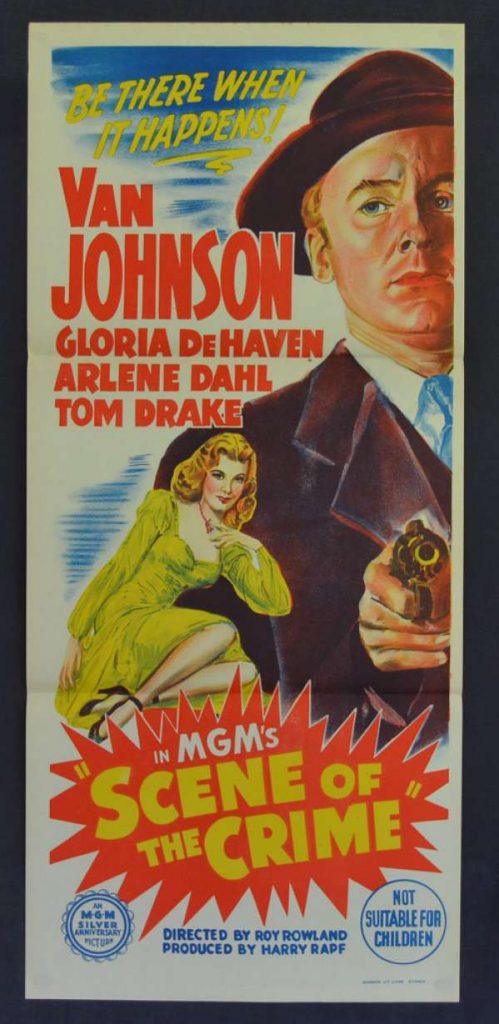

But he was soon back at war in the memorable Battleground (1949), and the early 1950s ushered in even more work – 16 movies between Grounds for Marriage (1951) and his final contract film for MGM, The Last Time I Saw Paris (1954), with Taylor. In this busy period he made his last film with Williams, Easy to Love (1953), played a sympathetic priest in When in Rome (1952) and an army captain in Siege at Red River (1954). Also in 1954 came the prestigious but dull Brigadoon.

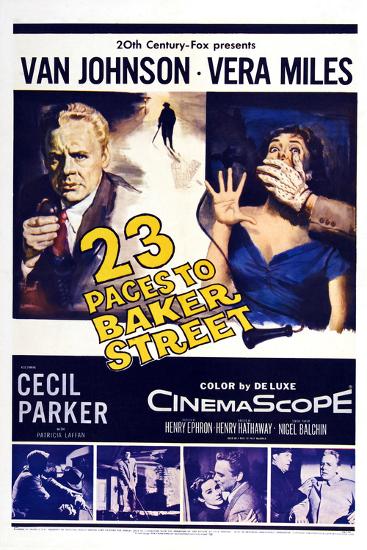

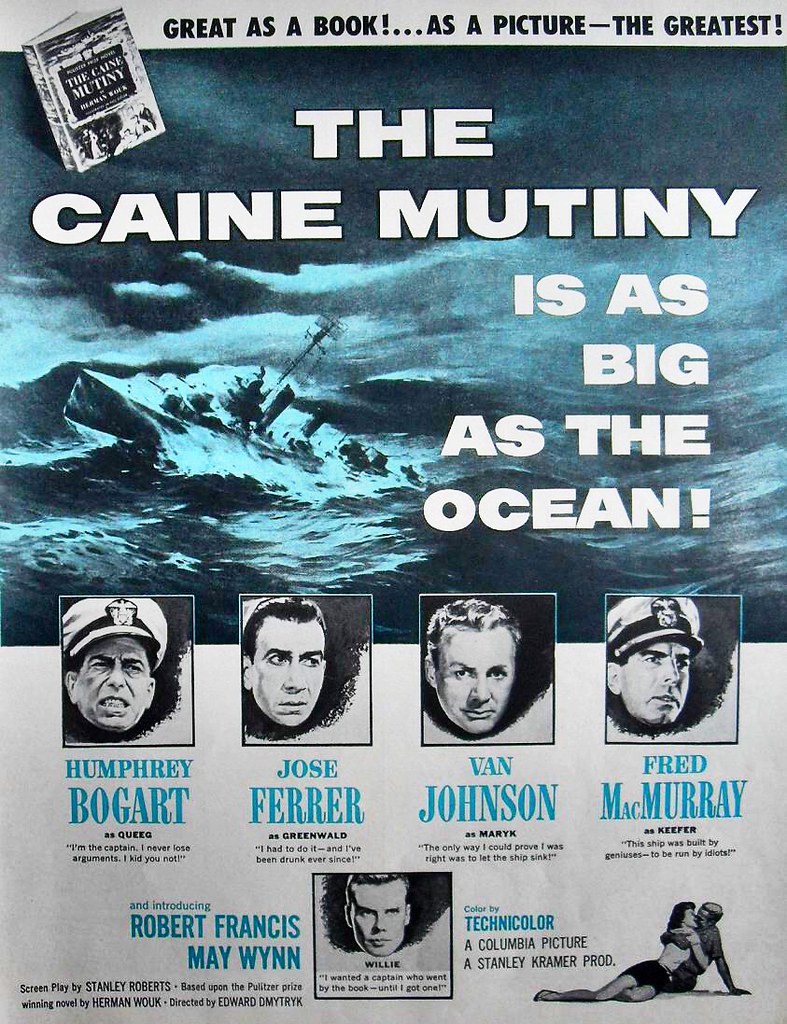

It looked for a while as though more characterful roles would beckon as he nudged 40. The best of these was in The Caine Mutiny (1954), playing Lieutenant Maryk, the officer who takes command when Captain Queeg (Humphrey Bogart) loses his marbles, only to find them again in the climactic court scene. His director, Edward Dmytryk, thought so highly of him that he (miscast) him in an adaptation of Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair (1955), playing the adulterous writer. Much criticism was levelled at the Americanisation of his character. Even so, he returned to Britain to play another writer in the thriller 23 Paces to Baker Street (1956). Here the writer, on the track of a murderer, was hampered by blindness, not guilt, and Johnson received better notices for this.

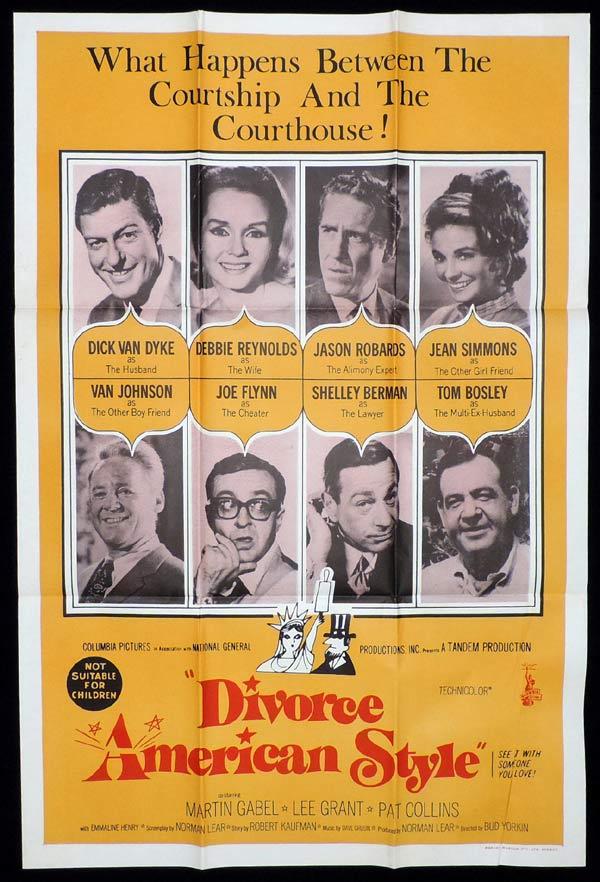

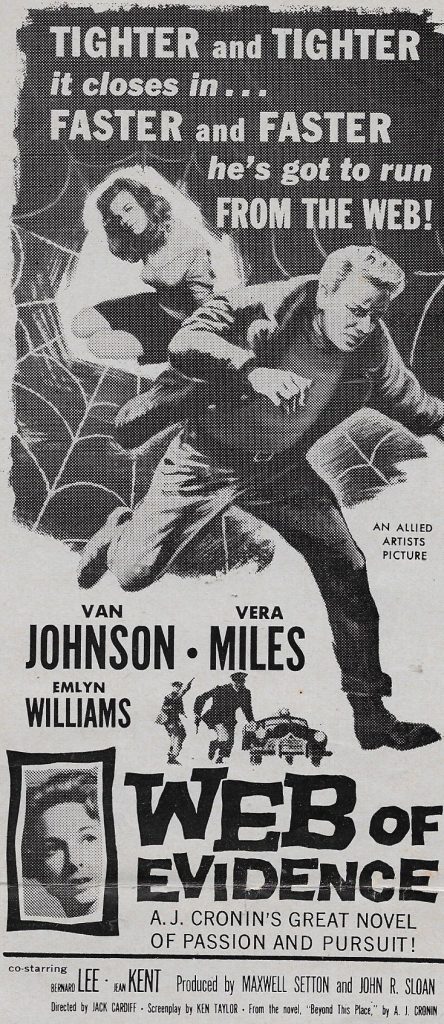

Sadly these meatier roles did not lead to a sustained change of direction. In 1957, he co-starred with a dog in the amiable Kelly and Me, and later that year took the title role in a television film The Pied Piper of Hamelin. Between then and the late 1960s he alternated between war movies (The Last Blitzkrieg and The Enemy General) and fun comedies (Wives and Lovers and the witty Divorce American Style), but never re-established his earlier fame.

Like other actors of his generation, Johnson found it easier to work in Europe and television, where his experience was more gratefully received than in Hollywood. In the late 1960s and 70s his work in Spain and Italy included Battle Squadron, The Price of Power and The Concorde Affair. These were squeezed between equally forgettable TV dramas such as Call Her Mom (as president) and mini-series such as Rich Man, Poor Man (1976).

I The 1980s and 90s were less busy. He was demoted to vice-president in The Kidnapping of the President (1990), a general in Delta Force Commando II (1990) and a captain in Taxi Killer (1988). There were further films in Italy and some TV work. Among all the dross was a role in Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985). Even this, playing a supporting role to the tedious antics of the stars, must have been more satisfying than the almost unseen Australian movie, Clowning Around (1992), where after taking fifth billing to a group of nonentities he quietly retired. According to the estimable film-writer Ephraim Katz he could, in his 80s, be found ensconced in a Manhattan penthouse, delighting in his cat Fred and his hobby of painting acrylics.

Though his screen image was generally lighthearted and he referred to himself as “Cheery Van”, Wynn remembered him as anything but. The deprivations of his childhood had made him moody and morose, his stepson wrote. “His tolerance of unpleasantness was minuscule. If there were the slightest hint of trouble with one of the children, or with the house, the car, the servants, the delivery of the newspaper, the lack of ice in the silver ice bucket, the colour of the candles on the dining-room table, Van immediately left the couch, the dinner table, the pool, the tennis court, the party, the restaurant, the vacation, and strode off to his bedroom.”

Johnson had married Ned’s mother, Eve Lynn Abbot, in 1947, only hours after she had divorced the actor Keenan Wynn, a friend of Johnson’s. They had one daughter, Schuyler, but divorced in 1968. Eve died in 2004.

• (Charles) Van Johnson, actor, born 25 August 1916; died 12 December 2008