John Mills obituary in “The Guardian” in 2005.

John Mills who has died aged 97, began his acting career in the theatre and returned quite frequently, and with distinction, to the stage in later years. But it was in the cinema that his energies were most often expended, and it is as a dependable British screen personality, over several decades and more than 100 movies, that he will primarily be remembered.

Mills’s background might be described as down to earth – he was born in Felixstowe, Suffolk, the son of a mathematics teacher, grew up in Norfolk, and worked briefly as a clerk before breaking into the theatre in 1929 in the chorus of a revue – and a quality of everyday realism seemed to cling to his best performances, without detracting from his stylistic range.

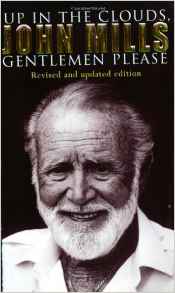

The title of his 1981 autobiography, Up In The Clouds, Gentlemen Please, derived from a backstage direction in his revue days. His gift for comedy may not often have been given full rein, but though he appeared in many routine films, his range as an actor went well beyond the military stereotypes with which he was perhaps too readily associated in the popular mind. Possibly his public image, particularly in later years, of trim avuncularity set off by a Garrick Club tie, served to compound this association.

Mills made his first film, The Midshipmaid, in 1932, and before the war appeared in juvenile leads and subsidiary parts in numerous pictures, some of them the once notoriously corner-cutting “quota quickies”.Advertisement

During the war, after being invalided out of the army, he made more substantial appearances in a variety of films, many of them service pictures such as In Which We Serve (1942), We Dive At Dawn (1943) and The Way To The Stars (1945). To some extent, these used him as a clean-cut officer-type, though not one devoid of irony or sensitivity. But at the same period, Waterloo Road (1944) showed him robustly at home in a working-class role, echoing his unpatronisingly drawn lower-deck character, ordinary seaman Shorty Blake, in In Which We Serve. And in one wartime picture, Cottage To Let (1941), he even characterised a Nazi fifth columnist, albeit in the guise of a dashing Spitfire pilot.

It was just after the war, however, with his Pip in David Lean’s film of Great Expectations (1946), that Mills fully came into his own as a screen performer. The subtlety and variety of his playing in this role were shortly to be seen again in two further literary adaptations, The History Of Mr Polly (1949, after HG Wells) and The Rocking Horse Winner (1950, after DH Lawrence), both of which he produced.

Mills later recalled: “I wasn’t a very good producer because I was always dying to get on the floor and didn’t really like the office work.” He suggested that Mr Polly did not succeed popularly at the time because “I was a blue-eyed hero up to then and audiences hated seeing me as a little wizened chap with smarmed hair, being a henpecked husband. But I wanted to make those two movies and now I’m rather proud of them.”

His “man on the run” in the thriller The Long Memory (1952) had a quality of grittiness more readily found in the French and American cinemas of the early 1950s than in the British – though he himself chose to describe the characterisation as “the old country’s answer to Jimmy Cagney” – while his cameo as the shabby private detective in the 1955 adaptation of Graham Greene’s The End Of The Affair carried the authentic whiff of Greeneland.

The year before, reunited with Lean for the period comedy Hobson’s Choice, he had provided a characterisation which had a representative blend of rumbustiousness and delicacy of detail. “It was the performance I have enjoyed most,” he said later. “Willie Mossop was a wonderful part, an unglamorous chap, but he was a hero.”

Over the next few years, Mills offered incisively scaled down performances in genre films like Town On Trial (1957, as a convincingly chip-on-the-shoulder detective) and Ice Cold In Alex (1958). He enjoyed making the latter, despite the gruelling desert heat of the location, but said with characteristically self-deprecating humour: “I was so disappointed in my love scene with Sylvia Syms. Up to then I had made love on the screen to virtually nothing but submarines and tanks, and this was my big chance – and then most of it was cut out.”

In 1960 came a full-blown, but far from self-indulgent, character study of a neurotically repressed army officer in Tunes Of Glory, in which he played opposite his friend of many years, Alec Guinness. “I’ve been asked a hundred times how I did the quivering eye bit,” he said, “but I’m not telling.” The performance brought him the best actor prize at the Venice film festival. However, Mills’s later claim that he and Guinness had tossed a coin as to which role each should play was one that the film’s director, Ronald Neame, was later at pains to deny.

In 1961 he appeared on Broadway in Terence Rattigan’s play about TE Lawrence, Ross (a role Guinness had played in the West End). During the 1960s, Mills gravitated, along with many other British actors of his generation, toward international movies – some, unfortunately, of a less than distinguished sort. Often these were costume pictures about historical personages, ranging from Lady Hamilton (1967) – he played the cuckolded Sir William Hamilton – to Lady Caroline Lamb (1972), with Mills as George Canning.

Mills never “went Hollywood”, but he appeared in occasional American films, among them a role as a US cavalry officer in the western Chuka (1967). He even played in a western series on US television, Dundee And The Culhane, as a British lawyer on the frontier, though it only lasted for one season. A more memorable television venture came later, on home ground, in Quatermass 4 (1979).

He also directed one film, Sky West And Crooked (1965), a rural melodrama conceived as a vehicle for his actor daughter Hayley Mills and written by his wife Mary Hayley Bell. The film proved a commercial flop. “You could have fired a shotgun in any Odeon where it was showing and not hit a soul,” he philosophically remarked.

Hayley Mills had made her screen debut at age 13 with her father in Tiger Bay (1959). However, her elder sister Juliet first appeared on screen as a three-month-old baby in In Which We Serve. Both daughters progressed to successful acting careers.

Perhaps Mills’s most worthwhile acting role at this time was in Bryan Forbes’s King Rat (1965). In a prison camp setting, Mills again, as in Tunes Of Glory (1960), delineated an outwardly correct figure succumbing to terminal strain. In 1969, his caricature of Haig in Richard Attenborough’s film of Oh! What A Lovely War had a florid skill, and the following year he was rewarded with the Academy Award for best supporting actor for his role as the village idiot in Lean’s Ryan’s Daughter, though this performance, with him smothered under grotesque make-up as an Irish village idiot, was not among his most notable.

During the 1970s, he made several returns to the West End theatre, appearing opposite Judi Dench in a musical version of The Good Companions, in a revival of Separate Tables, and in Little Lies. Later, he was content to essay supporting film roles, as with his portrayal of yet another military man, albeit in period garb, in the 1978 remake of The 39 Steps.

He was made a CBE in 1960 and knighted in 1976.

His last substantial role in the cinema was, somewhat incongruously, with Madonna in the comedy Who’s That Girl? (1987), but even in these curious circumstances he showed that he had lost nothing of that practised ease which made him for so long such a durable presence in the British cinema’s acting ranks.

His sight was increasingly impaired in his last years and he had been almost blind since 1992, but he continued to make occasional television appearances, notably in the serial of Martin Chuzzlewit (1994).

Subsequently, he returned to cameo roles in films as diverse as the comedy Bean (1997) and Kenneth Branagh’s all-star version of Hamlet (1996). He also travelled the country in a one-man show of reminiscences, full of pawky anecdotage and even the occasional song. When the interval arrived, he was apt to confide in the audience that he was repairing for “a Mars bar and a Guinness”.

Nor did he disappear from the public gaze in a more formal context. His 90th birthday was the occasion for several television interviews, and in the summer of 2000 he delivered an address in homage to Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother on her 100th birthday at a ceremony in Horseguards Parade, despite the fact that he was only eight years her junior.

The following year, he “made it up” to his wife for the fact that their wartime wedding had been a somewhat utilitarian affair by “remarrying” her in fine style at the village church close to their Berkshire home. This happy occasion was a suitably theatrical gesture by a man who had come to be seen as an elder statesman of the British acting profession.

He appeared earlier this year as A Tramp in a short titled Lights2.

He is survived by his wife; their two daughters; and a son, Jonathan Mills, a screenwriter.

· John Lewis Ernest Mills, actor, producer and director, born February 22 1908; died April 23 2005