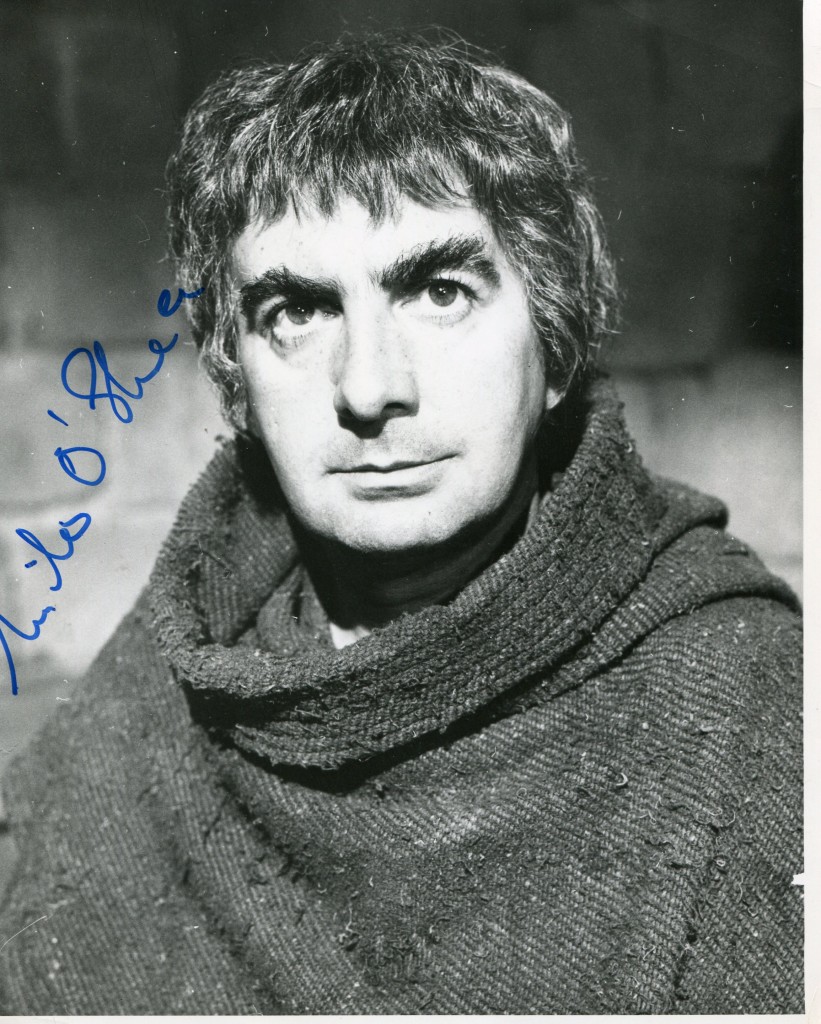

Milo O’Shea obituary in “The Guardian” in 2013.

Great Irish character actor who starred as Leopold Bloom in Joseph Strick’s adapatation of James Joyce’s “Ulysses” and as ‘Friar Laurence’ in the 1968 film version of “Romeo and Juliet”. He also starred with Paul Newman, James Mason and Charlotte Rampling in “The Verdict”. He moved to the U.S. and died in New York in 2013.

Michael Coveney’s obituary in “The Guardian”:

For a performer of such fame and versatility, the distinguished Irish character actor Milo O’Shea, who has died aged 86, is not associated with any role in particular, or indeed any clutch of them. He was chiefly associated with his own expressive dark eyes, bushy eyebrows, outstanding mimetic talents and distinctive Dublin brogue.

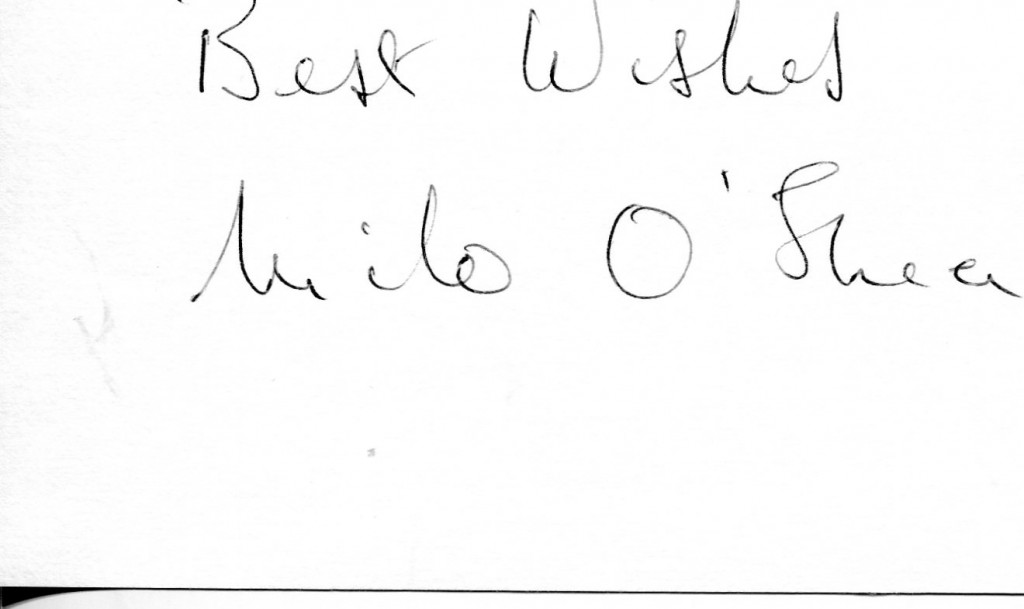

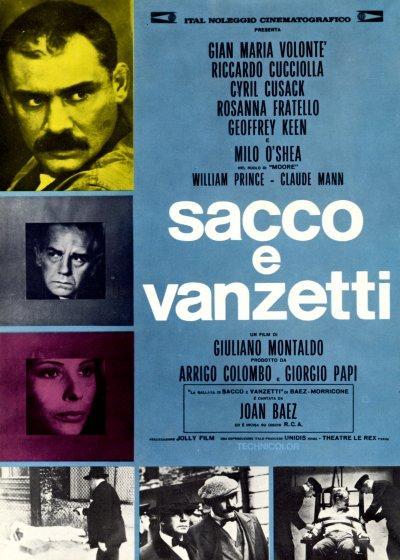

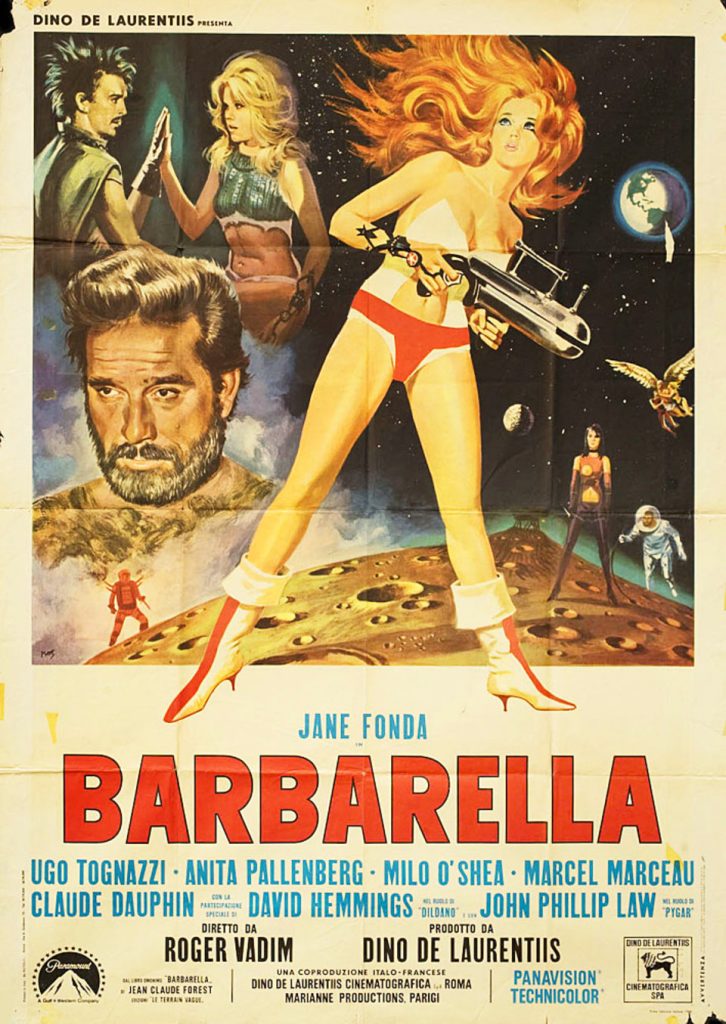

His impish presence irradiated countless fine movies – including Joseph Strick‘s Ulysses (1967), Roger Vadim‘s Barbarella (1968) and Sidney Lumet‘s The Verdict (1982) – and many top-drawer American television series, from Cheers, The Golden Girls and Frasier, right through to The West Wing (2003-04), in which he played the chief justice Roy Ashland.

He had settled in New York in 1976 with his second wife, Kitty Sullivan, in order to be equidistant from his own main bases of operation, Hollywood and London. The couple maintained a penthouse apartment overlooking Central Park by the Dakota building, and formed a spontaneous welcoming committee for any Irish actors or plays turning up on Broadway.

Although he had worked for Hilton Edwards and Micheál MacLiammóir at the Gate theatre in Dublin, and returned there in 1996 to appear in a revival of Neil Simon’s The Sunshine Boys opposite his great friendDavid Kelly, his Irish theatre connections belonged to the city of his youth, and he preferred it that way.

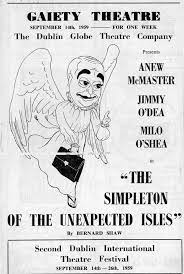

His father was a singer and his mother a ballet teacher, so it was inevitable, perhaps, that Milo gravitated towards the stage. He was just 12 when he appeared in Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra at the Gate. He completed his education with the Christian Brothers at the Synge Street school (where the actor Donal Donnelly was a classmate) and took a degree in music and drama at the Guildhall School in London; he remained a superb pianist all his life and could – and usually did – sit down at the keyboard and play more or less anything.

He made a London debut in 1949 as a pantry boy in Molly Farrell and John Perry’s Treasure Hunt at the Apollo, appearing in John Gielgud‘s production of the jewellery-theft potboiler alongside Sybil Thorndike, Marie Lohr and Alan Webb. When Queen Mary came backstage, she asked O’Shea where the gems had gone. “Don’t tell her,” whispered Thorndike, “or she won’t come back after the interval.”

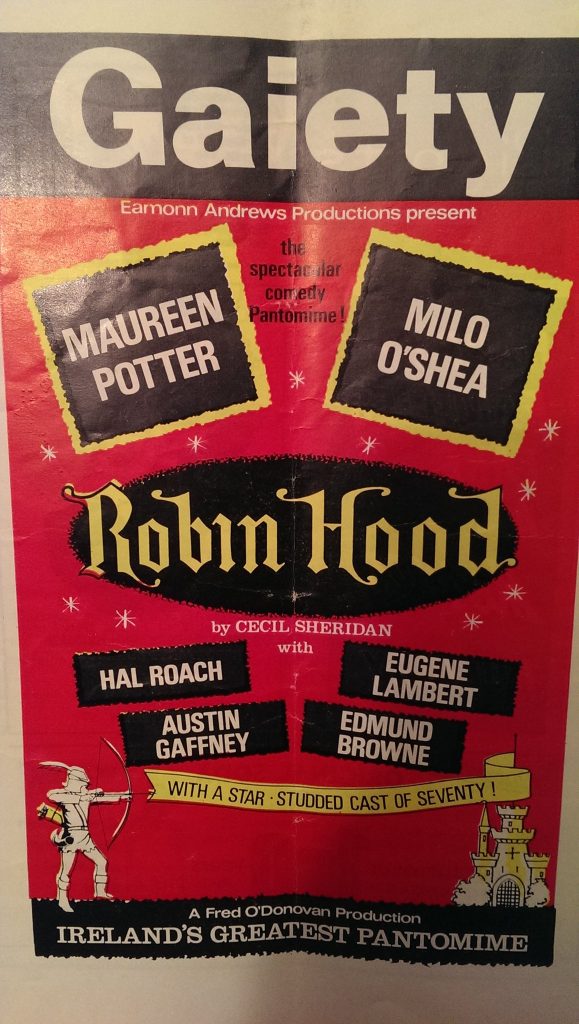

Back in Dublin, he appeared in revues at the 37 Theatre Club on Lower O’Connell Street and was part of a group including Maureen Toal, whom he married in 1952, Norman Rodway and Godfrey Quigley at the Globe, as well as appearing at the Pike. He toured America with Louis D’Alton’s company and played a season at Lucille Lortel’s White Barn theatre in Westport, Connecticut.

The 1960s started inauspiciously with a brief run at the Adelphi in London in Mary Rodgers’s Once Upon a Mattress, which lasted just 38 performances. But Brendan Behan had seen and loved Fergus Linehan’s musical Glory Be! and recommended it to Joan Littlewood, who presented it for a season at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, in 1961. O’Shea was a hit, leading a cast of young Dublin actors including Kelly and Rosaleen Linehan. Some critics mistook youthful buoyancy for amateurism and likened the show to Salad Days, suggesting it be renamed “Mayonnaise”.

By the end of the decade, O’Shea was fully established on Broadway, winning a 1968 Tony nomination as one of Charles Dyer’s two gay hairdressers in Staircase (the other one was Eli Wallach) and appearing opposite Angela Lansbury as the sewerman in Jerry Herman’s Dear World in the following season.

Around the same time, two major movie performances, following Strick’s admirable but unsatisfactory Ulysses (O’Shea was Leopold Bloom), confirmed his status: as the mad scientist Durand Durand (inspirational name for Simon Le Bon’s pop group Duran Duran), he was seen gibbering ecstatically as he tried to destroy Jane Fonda’s Barbarella with simulated lust waves in his Excessive Machine; and as Friar Laurence in Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet (1968) he brought brief hope and humour to the carnally doomed coupling of Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey.

And in 1969 he struck sitcom gold in the BBC’s Me Mammy, scripted by Hugh Leonard, in which he played bachelor Bunjy Kennefick, a West End executive with a luxury flat in Regent’s Park and a mountainous mum, played by Anna Manahan, with her apron strings tied round his neck. The show ran for three series to 1971, and O’Shea was now a household face on both sides of the Atlantic.

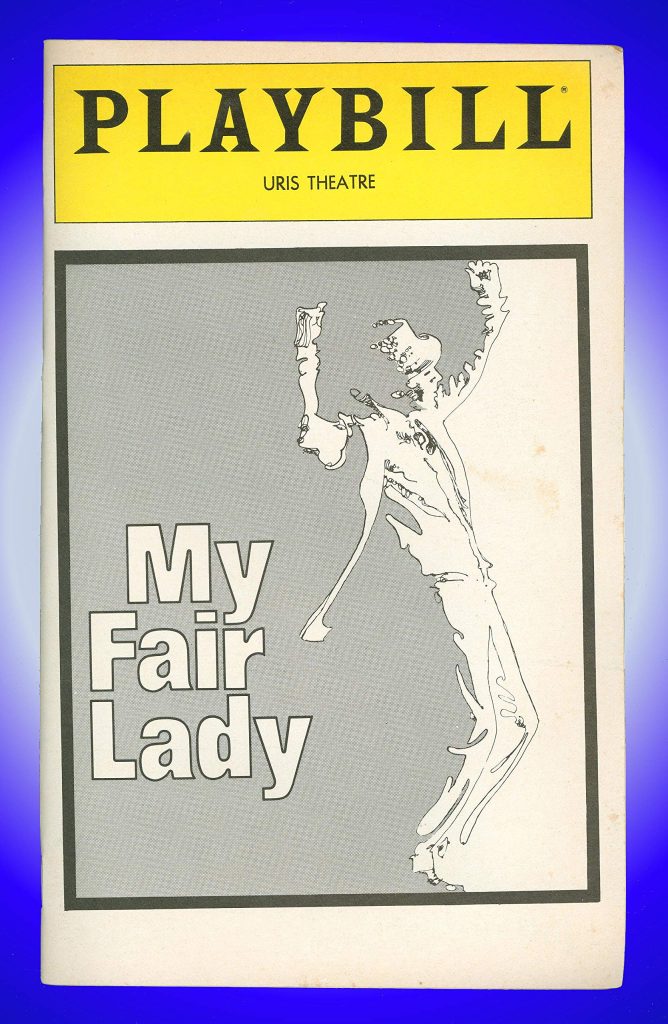

After the move to Manhattan, he appeared on Broadway as Eddie Waters, the failed old comedian, in Mike Nichols’s production of Trevor Griffiths’s Comedians; as James Cregan in Eugene O’Neill’s extraordinary A Touch of the Poet, with Jason Robards and Geraldine Fitzgerald; and as Alfred Doolittle in a 1981 revival of My Fair Lady, once again starring Rex Harrison.

But he won his second Tony nomination for his luxury-lifestyle-loving Catholic priest, Father Tim Farley, in Bill C Davis’s debut Broadway play, Mass Appeal in 1982. The critic Frank Rich applauded his comic mischievousness and timing, and noted how the mask slipped on the sham of a life of this lost alcoholic soul who was inducting a rebellious young seminarian; the play was finally about secular and religious love, not the Catholic church at all.

Unfortunately, O’Shea did not return to London with Mass Appeal, but with Gerald Moon’s Corpse! at the Apollo in 1984. He played an Irish war veteran trapped in a basement with Keith Baxter; Baxter was playing a pair of effete twins who each wanted to kill the other (without success, alas). The play was as moribund as its title.

O’Shea will survive, though, whenever we catch a glimpse of him in Silvio Narizzano‘s odd version of Joe Orton’s Loot (1970), or as yet another priest in Neil Jordan’s weird and wonderful The Butcher Boy (1997), or as an incredulous inspector in Douglas Hickox’s critic-baiting Theatre of Blood (1973), or holding the ring between Paul Newman and James Mason, his hair slightly longer than usual, as the trial judge in The Verdict (1982).

His last stage appearance was a homecoming of sorts as Fluther Good in Sean O’Casey’s tremendous tenement tragedy The Plough and the Stars 12 years ago at the Guthrie Theatre in Minneapolis, directed by Joe Dowling, with Linehan as Bessie Burgess.

He is survived by Kitty and by his two sons, Colm and Steven, from his first marriage, which ended in divorce in 1974.

• Milo O’Shea, actor, born 2 June 1926; died 2 April 2013

His Guardian obituary can be accessed here