“Independent” obituary by David Shipman from 1994:

Giulia Anna Masina, actress: born Giorgio di Piano, Italy 22 February 1920; married 1943 Federico Fellini (died 1993); died Rome 23 March 1994.

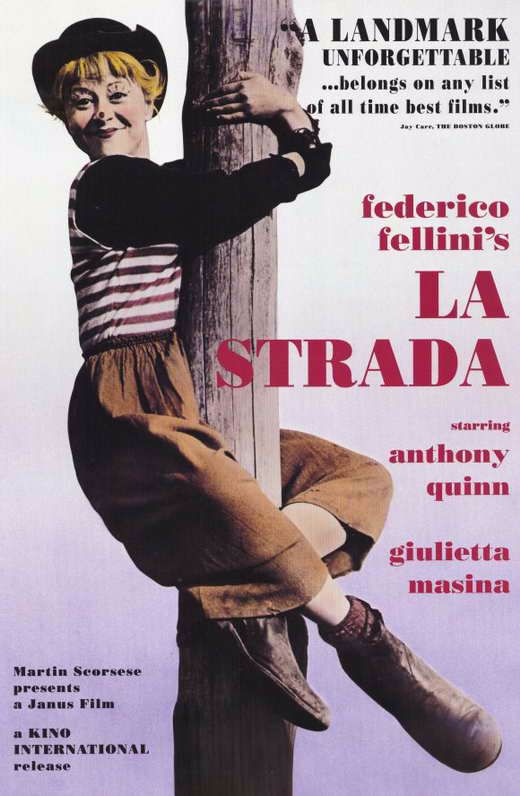

THE ADJECTIVE which has been over-used to describe Giulietta Masina is ‘Chaplinesque’, as she laughed through the tears which cascaded down her clown’s face. There had been no female star before quite like her, and she had the world at her feet when she appeared in La Strada (1955), prepared for her and directed by her husband, Federico Fellini.

There was a decided difference of opinion about the movie: it was either a calculated assault on our tear-ducts or it was a poetic essay on the lot of strolling players in rural Italy. There were moments when you caught your breath, when Fellini captured the beauty and tranquillity of small Italian towns at night, and there were moments when he reached too far back to the traditions of commedia dell’arte.

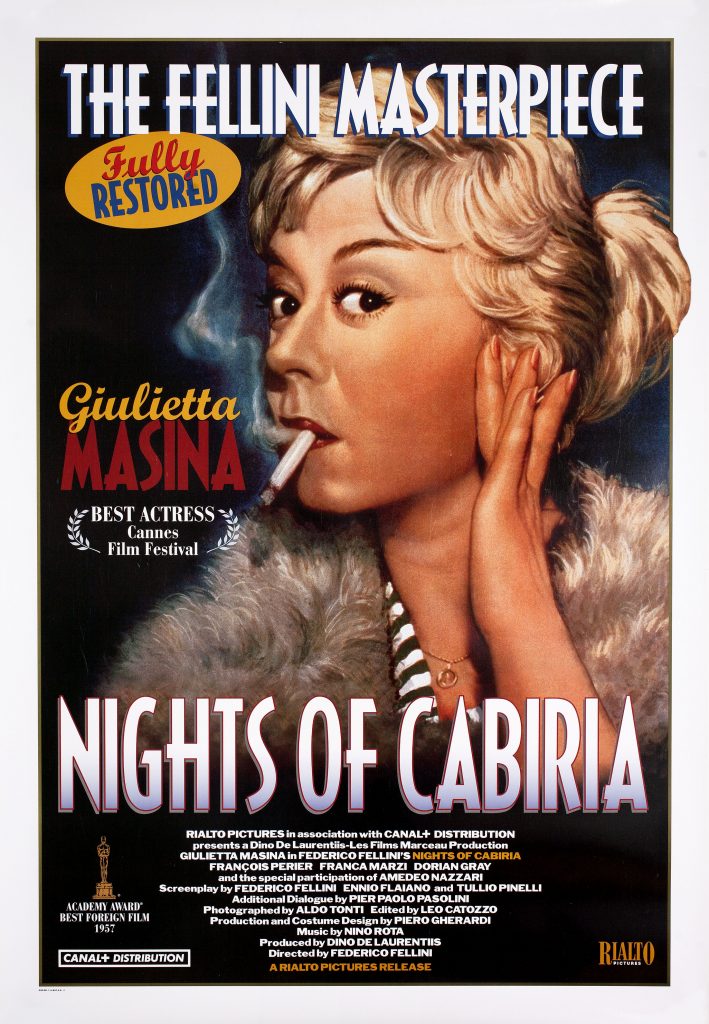

He sculpted another monument to the comic-tragic abilities of his wife in Le Notti di Cabiria (1957). These abilities were genuine. As the critic Paul Dehn wrote, after noting that she ‘deserves a single name as surely as Garbo or Chaplin’, ‘She is a miniature version of the hope which still persists in a bloody world: and the world itself would be lost if it did not love her.’

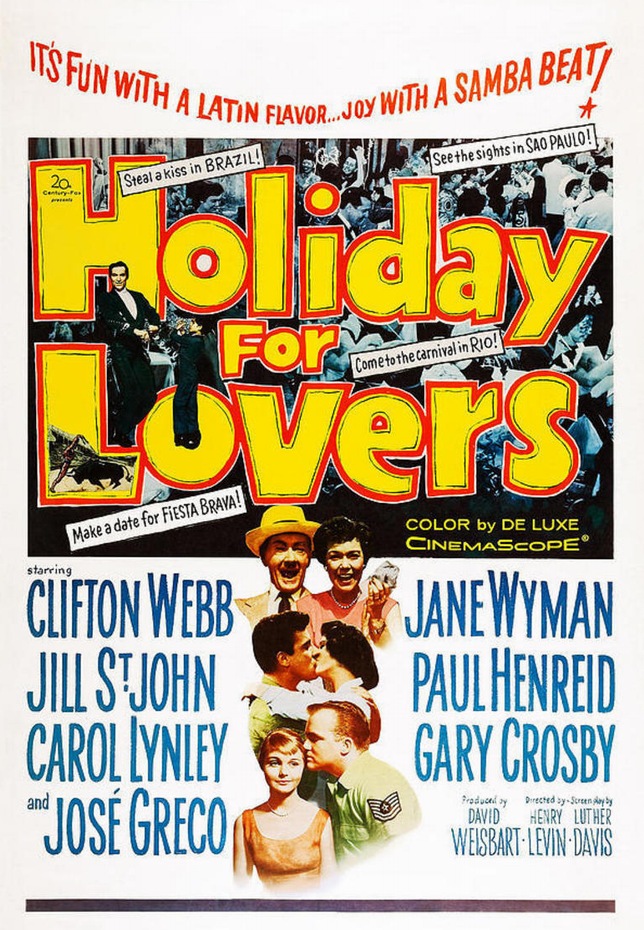

There seldom was a more optimistic hooker than the one played by Masina in Cabiria (as the film was best-known abroad), though the adjective in this case might be obtuse, for the viewer knows – if she doesn’t – that the nice, respectable man (Francois Perier) to whom she has loaned her nest-egg will abscond with it. The enormous success of both films typecast her. She played the role again in Eduardo de Filippo’s Fortunella (1958) and for Julien Duvivier in La Grande Vie (1959).

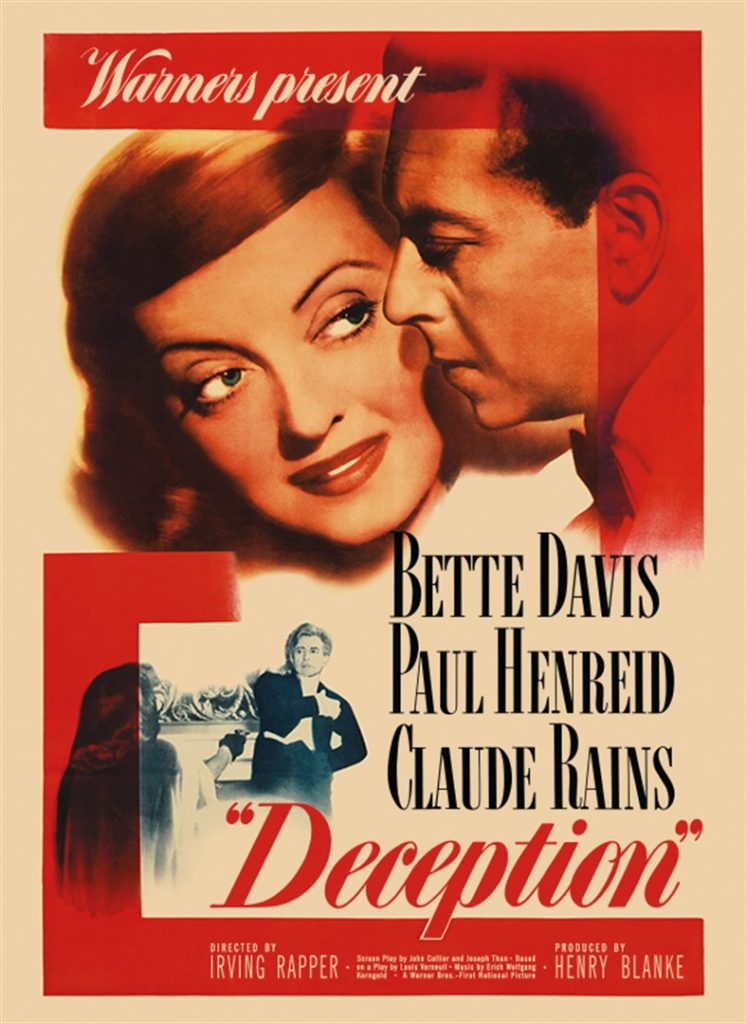

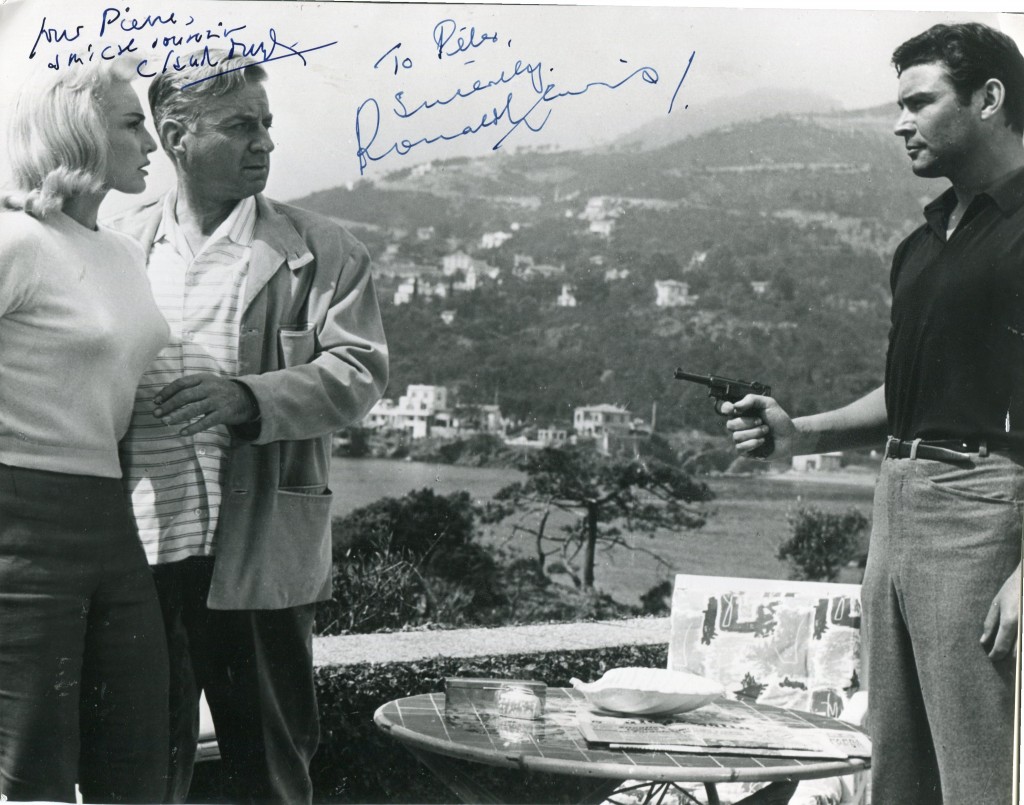

Masina lacked the demonic power of her contemporary (and co-star, in Nella Citta l’Inferno, 1958) Anna Magnani. On both sides of her brief reign of acclaim she was fated to play the role of the heroine’s friend or confidante – in for instance Alberto Lattuada’s brilliant study of conditions in post-war Italy, Senza Pieta (1948), helping her fellow whore Carla Del Poggio, and Roberto Rossellini’s Europa ’51 (1952), comforting her fellow socialite Ingrid Bergman. There was no chance here for the pyrotechnic displays of her later star vehicles, but she showed herself an artist of resource, integrity and dignity. Between La Strada and Cabiria Fellini gave her another chance to underplay, in one of his best and least pretentious films, Il Bidone (1955), an engaging comic melodrama about the retribution dealt out to con-men, including Broderick Crawford and Richard Basehart. Masina’s role, as Basehart’s wife, was not of long duration, but you could agree with the hyperbole evoked by the critic of Time and Tide – ‘She is one of those performers you can’t bear to tear your eyes from’ – though he was in this case reviewing Cabiria.

Cabiria brought Masina a Best Actress award at the Cannes Film Festival, but the failure of a handful of co-productions with France and Germany spoiled her chances of an international career. She was one of the victims of the mass-murderer Landru (1963) in Claude Chabrol’s comedy-thriller, but with much less footage than some of the others, who included Michele Morgan and Danielle Darrieux. She was on screen for about the same time in her only English-language film, the disastrous The Madwoman of Chaillot (1969), but as one of Katharine Hepburn’s coven she was one of the few names of the starry cast (Danny Kaye, Charles Boyer, Richard Chamberlain) to emerge with credit.

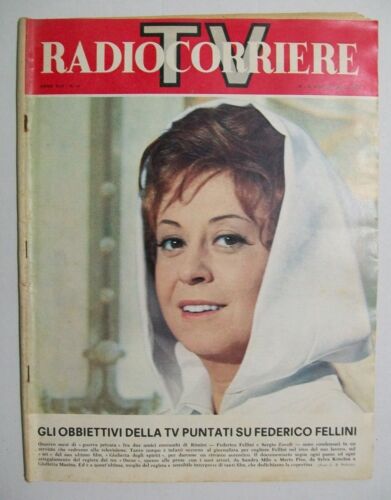

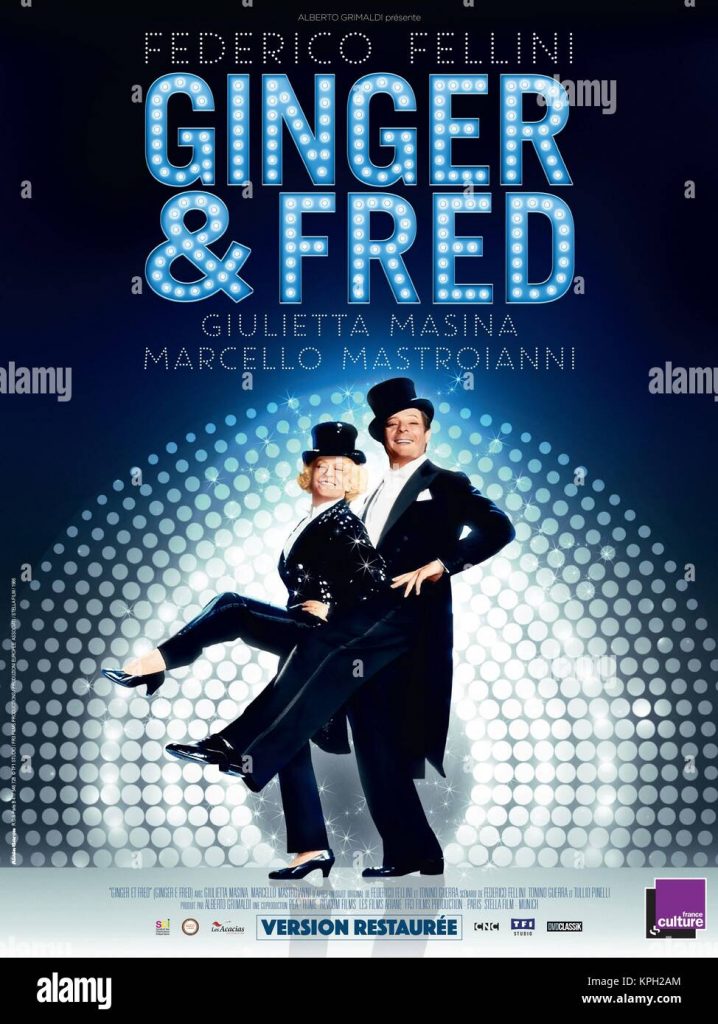

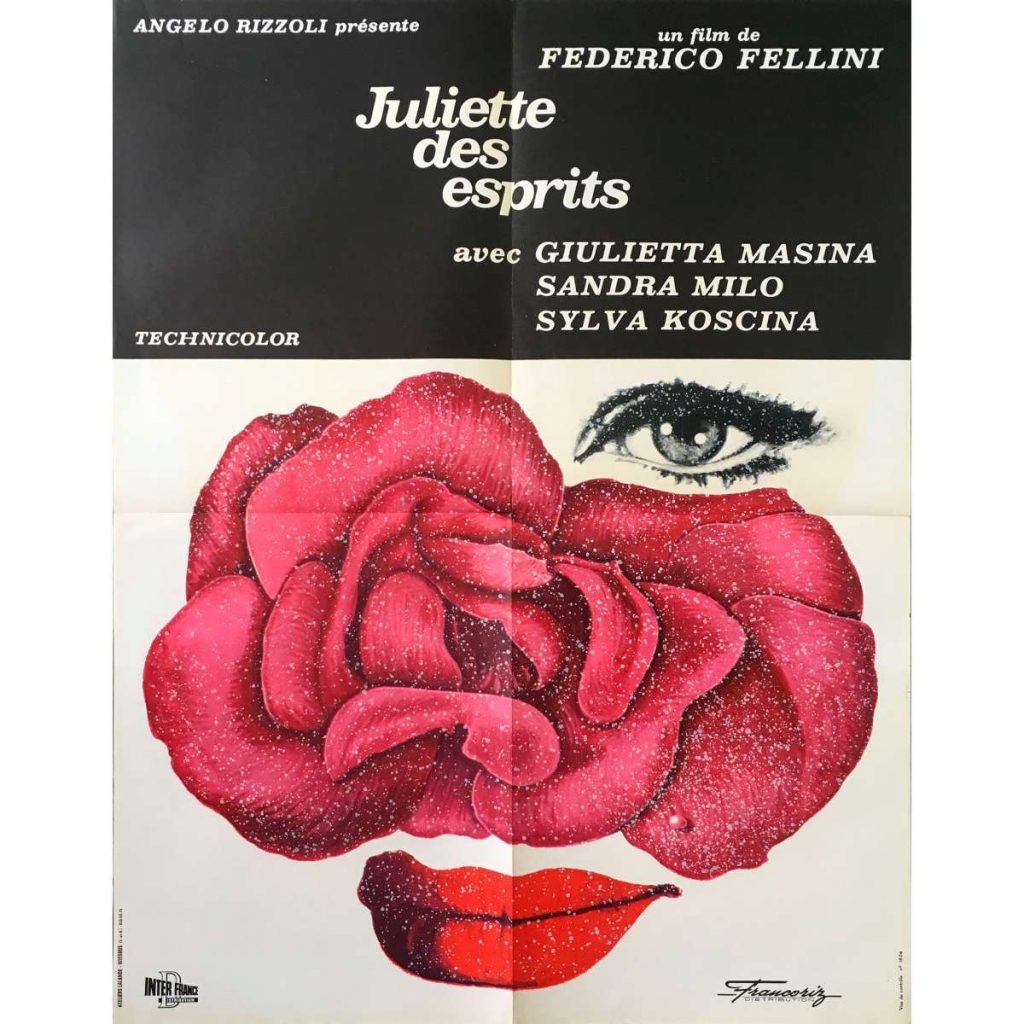

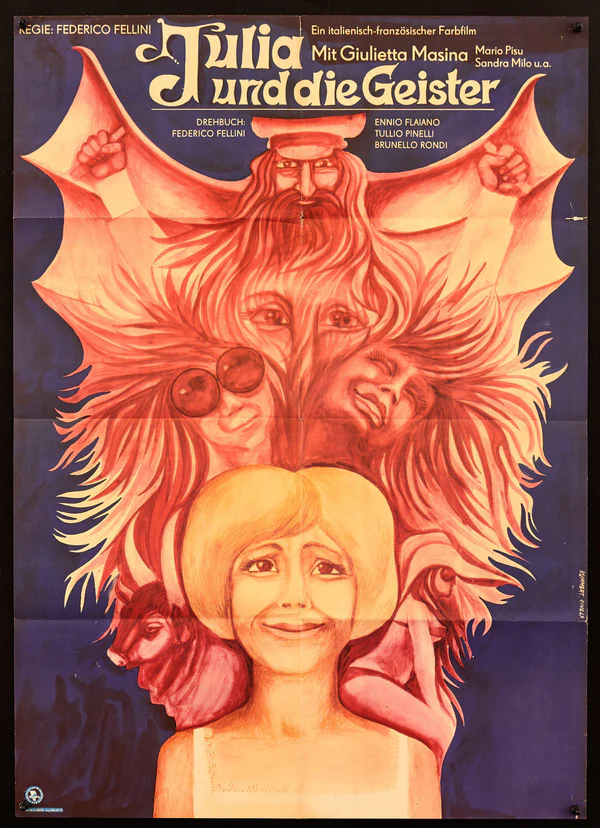

When Fellini really attracted world attention with La Dolce Vita in 1960 Masina was busy enough being his wife and chatelaine – roles she played for him on screen in Giulietta degli Spiriti (1965), a follow-up to his autobiographical 8 1/2 , even more fantastical and self-indulgent. Her few later films only contain one role of consequence, when she starred opposite Fellini’s frequent alter ego Marcello Mastroianni in Ginger e Fred (1985), yet another of his obsessive studies of the hollow dreams and aspirations of those besotted with show business.

That was where they came in. His first film with her and his first as director was Luci del Varieta (1950), a tale of a tatty touring company which played to mixed results in the country’s shabbier halls. It was one suffused with melancholy, made with a wit and compassion many feel were missing from his later films. And Masina was touching and discreet. It was a far cry from the junketings of Giulietta degli Spiriti (1965).

The “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.