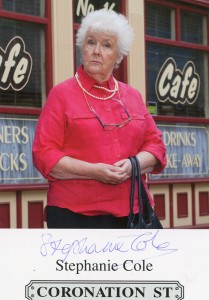

Stephanie Cole auditioned for, and was accepted by, the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School at the age of 15. She made her stage debut there two years later, playing a 90-year-old. Since that auspicious beginning, Cole’s extensive theatre credits have included Rose (starring Glenda Jackson at the Duke of York’s), Noises Off (Savoy), Steel Magnolias (Lyric) and The Relapse (Old Vic).

In 1995, she starred in Kay Mellor’s A Passionate Woman which played to packed houses at the West End’s Comedy Theatre for an extended nine-month run. More recently, she was back in the West End co-starring with Donald Sinden in Ronald Harwood’s Quartet.

On television, Cole’s many regular appearances have included Tenko, Keeping Mum, Life as We Know It, Talking Heads and A Bit of a Do. She won a British Comedy Best Actress award forWaiting for God. A familiar voice in radio drama, the actress has recently published her autobiography, entitled A Passionate Life.

The actress is currently starring in the UK-wide tour of So Long Life, a new work by the award-winning Peter Nichols. She plays an 85-year-old matriarch (pictured), whose extended and highly dysfunctional family gathers to celebrate her birthday. Following its tour, the play is expected to transfer to the West End.

Place of birth

Born in Solihull, Warwickshire.

Now lives in

Somerset

Trained at

Bristol Old Vic School

First big break

When the television series Tenko and Open All Hours ran concurrently, it enabled me to be offered more major roles in both comedy and drama.

Career highlights to date

Both Talking Heads and Waiting for God for the BBC, and A Passionate Woman (1995) at the Comedy Theatre.

Favourite productions you’ve ever worked on

It’s usually the one I’m working on now, and in this case it certainly is. I think So Long Life is a terrific play.

Favourite co-star

There have been so many lovely ones, that to pick any single one out would be invidious.

Favourite director

There are probably two. Ned Sherrin for offering up fun and food, and Dominic Hill for the brilliant direction he provides.

Favourite playwright

There are many, many playwrights I love, stretching from Shakespeare to Alan Bennett. But Peter Nichols is perhaps still the tops for me.

What role would you most like to play (if you haven’t already)?

I would contemplate anything that was new and also well-written.

How do you think the theatre and television industries have changed since you began your acting career?

I feel that theatre has changed completely, and for the worse as far as young actors are concerned, with the slow demise of the repertory system. And television has dumbed down to such an extent that there are very few decent scripts. With regards to the financial situation, it’s take it or leave it – which is hard for the ordinary working actor.

In your opinion, what’s the best thing currently on stage?

Joe Penhall’s Blue/Orange.

What advice would you give to the government to secure the future of British theatre?

Pour more money in and put people in charge of organisations who actually know what they are doing.

If you could swap places with one person (living or dead) who would it?

No one especially, unless I could be Tony Blair briefly and divert extra money into caring for the mentally ill.

Favourite book

The poems of Edward Thomas.

Favourite joke

I laugh like a drain at most jokes, but then instantly forget them so I can’t help!

Why in particular did you want to accept your part in So Long Life?

Because the character of Alice represents a feisty 85-year-old from Bristol, and I am a West Country girl.

Peter Nichols is enjoying a resurgence with major revivals of A Day in the Death of Joe Egg, Privates on Parade etc. To what would you attribute this renewed interest in his work?

Simply the fact that he is one of the great playwrights, and I think it is a disgrace that he was ignored for so long.

Are there any special considerations when performing a new work by Nichols as opposed to one of his “tried and tested” pieces?

The main consideration is that working with a playwright on a new play is the most creative and exciting journey of discovery.

What’s your favourite line from So Long Life?

I’d probably be giving too much away if I revealed anything.

What was the funniest, or oddest, moment during rehearsals for So Long Life?

Despite the fact that we did laugh a great deal in rehearsals, no single incident springs to mind.

What are your plans for the future?

I sincerely hope that So Long Life gets the West End run that it fully deserves.

– Stephanie Cole was speaking to Terri Paddock

The above “What;s On Stage” article can be accessed also online here.