John McEnery obituary in “The Guardian” in 2019

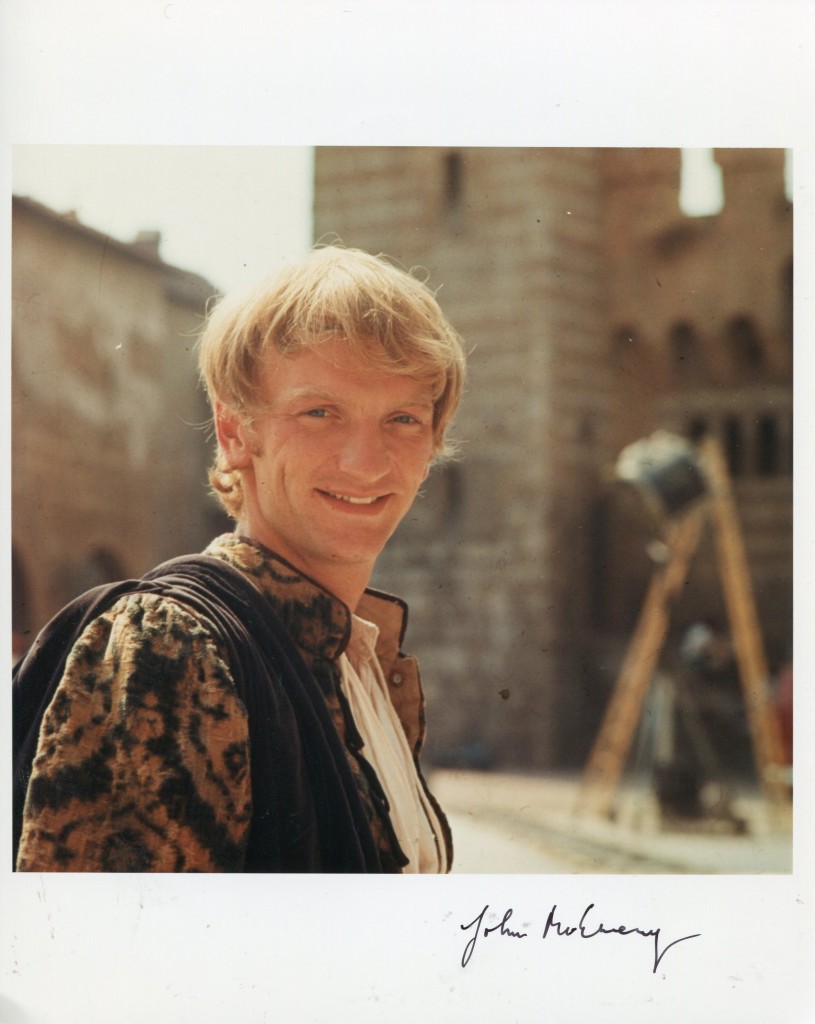

John McEnery, who has died aged 75, was an intuitive actor in the abrasive style of Nicol Williamson, whom, in some respects, he resembled: tall and rangy, with a thatch of blond hair, a default setting of sardonic indifference, piercing blue eyes, and a voice that could rasp like sandpaper and dissolve in mildly suppressed emotion.

Also, like Williamson, McEnery was a dedicated hellraiser, a free spirit who, said his former wife, the actor Stephanie Beacham, woke up each morning and invented how to live. Despite this innate unpredictability, his talent blazed when he played Mercutio in Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 film version of Romeo and Juliet, a performance that won him a Bafta nomination and, briefly, a European and Hollywood reputation.

His elder brother, the actor Peter McEnery, a smoother sort of jeune premier, had made a film with Roger Vadim and Jane Fonda, La Curée (The Game Is Over), in 1966; John followed suit, co-starring with Jean-Pierre Cassel and Claude Jade in Gérard Brach’s Le Bateau sur l’Herbe (The Boat on the Grass) five years later. But, beyond a striking appearance as Kerensky in Franklin Schaffner’s sumptuous Nicholas and Alexandra (also 1971), he was unconcerned about structuring a career.

This did not deter him from accumulating some impressive spells with both Laurence Olivier’s National Theatre in the late 1960s and Trevor Nunn’s Royal Shakespeare Company in the mid-70s, culminating in a splendid double of the spendthrift Mantalini and theatrical all-rounder Snevellicci in the celebrated Nicholas Nickleby in 1980.

He found a third “home” at Shakespeare’s Globe under Mark Rylance, where he played a caustic Fool to Julian Glover’s Lear in 2001, another great double as John of Gaunt and the senior gardener (“Go, bound thou up yon dangling apricocks”) in Mark Rylance’s all-male Richard II in 2003, and as an original, persuasive Shylock in 2007.

His offstage life became increasingly rackety. Latterly, he combined living in a hostel near St Leonard’s, in Shoreditch, east London, (where his hero, Shakespeare’s leading man, Richard Burbage, is buried) with playing large roles for the small-scale Malachite theatre in the church.

In 2015, he played a moving but unsentimental King Lear which transferred for a short season to the exposed remains of the Rose, Bankside’s first playhouse in 1587, just 50 yards from the new Globe.

Having then moved into a basement flat on the Isle of Sheppey, he was arraigned in 2017 for having brandished a water pistol in a pub in Faversham, but was cleared of all charges of intent to cause fear and violence one year later when he and a friend were dismissed by the court in Maidstone, where he appeared in shorts and sandals, as “two old fools having a laugh”. Here indeed was Lear on the blasted heath.

Born in Walsall, near Birmingham, John was the third son of Charles McEnery, who owned and managed a pickle factory, Mack’s Pickles, and his wife Mary (nee Brinson). Charles sold the factory and moved with the family to Brighton, East Sussex, mainly to benefit the health of the eldest boy, David, who had rheumatic fever.

There, and in Hove, he opened four stationery shops. John attended the Dorothy Stringer secondary modern school (now Dorothy Stringer high school, a comprehensive) and worked in a department store before taking the plunge into theatre.

He trained at the Bristol Old Vic in 1962, just as Peter established himself as a shooting star at the new RSC under Peter Hall. His first job, in 1964, was in the newly founded Everyman theatre in Hope Street, Liverpool. McEnery stayed for three years, in a company that included Terry Hands, Susan Fleetwood, Terence Taplin and Beacham.

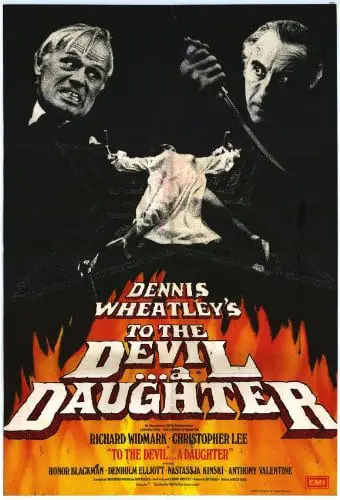

He then joined the National Theatre at the Old Vic, appearing in the premiere of Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1967) as Hamlet, upstaged by his own courtiers. Other notable new NT plays included Peter Shaffer’s The Royal Hunt of the Sun and Charles Wood’s H, and he was a very funny Costard in Olivier’s production of Love’s Labour’s Lost. After Romeo and Juliet, his film career imploded save for the title role in Anthony Friedman’s Bartleby (1970) opposite Paul Scofield, as Captain van Schoenvorts in the dinosaur adventure The Land That Time Forgot (1974) and as an amiable second in Ridley Scott’s The Duellists (1977).

At the Nottingham Playhouse in the 70s, he returned to Stoppard’s quizzical play, taking the title role opposite brother Peter as Guildenstern and renewed his relationship with Beacham when they appeared together in Harold Pinter’s The Homecoming; they married in 1973 and had two daughters, but divorced five years later. Beacham remained in touch at the end of his life.

At the RSC from 1975, McEnery played a string of important roles – Private Meek in Shaw’s Too True To Be Good, Antonio in Middleton and Rowley’s The Changeling, Andrew Aguecheek in Twelfth Night, Roderigo in Donald Sinden’s Othello, with Bob Peck as Iago, and Pistol in a 1979 Merry Wives directed by Nunn and John Caird in a company – Timothy Spall, David Threlfall, Ben Kingsley – that prefigured the Nickleby experience.

His best television appearances included John Harmon, opposite Jane Seymour’s Bella Wilfer, in a BBC Our Mutual Friend (1976), the Rev Francis Davey, again with Seymour, in Jamaica Inn (1983) and Uncle Ted in Hanif Kureishi’s autobiographical The Buddha of Suburbia (1993). Later films included Peter Medak’s The Krays (1990), Mr York in Caroline Thompson’s Black Beauty (1994) and the apothecary in Peter Webber’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003).

He was the kind of actor you could not see without thinking how good he was, still and dangerous, ticking like a time bomb, but his reputation with the public was unfocused. He was terrific again at the RSC in Sam Shepard’s dysfunctional family drama Curse of the Starving Class in 1991, and, 10 years later, as a bogus Quaker ancestor in Nick Stafford’s Luminosity.

His last mainstream stage performance came at the Young Vic in 2012, when he played an old gardener, who seduces a starving girl, in a revival of Edward Bond’s Bingo with Patrick Stewart as Shakespeare and Richard McCabe as Ben Jonson.

McEnery is survived by his daughters, Phoebe, who played Regan to his King Lear, and Chloe, and by Peter. His eldest brother, David, a photographer, predeceased him.

• John Murray McEnery, actor, born 1 November 1943; died 12 April 2019