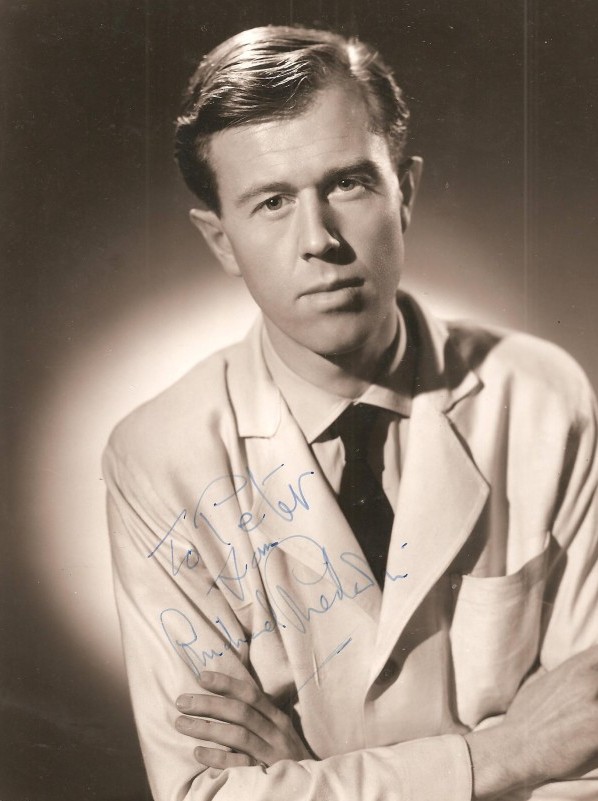

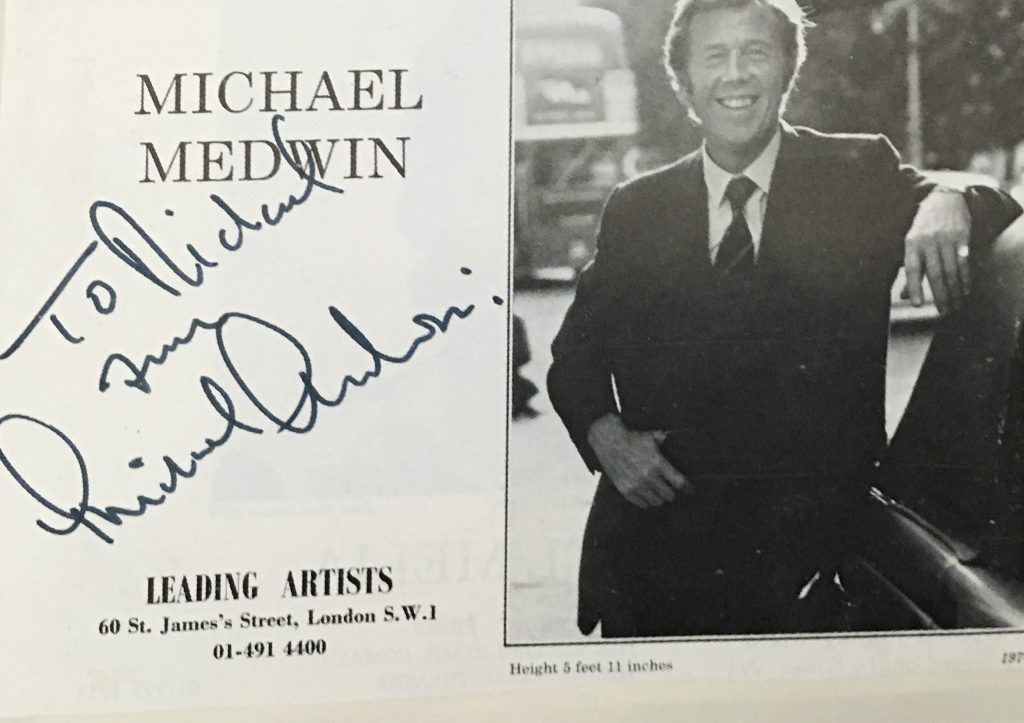

Michael Medwin was born on July 18, 1923 in London, England as Michael Hugh Medwin. He is an actor and producer, known for The Duchess (2008), Three Live Wires (1961) and Scrooge (1970).

Michael Medwin obituary in “The Guardian” in 2020.

Best known for countless character roles in films and as the wide-boy Corporal Springer in the highly acclaimed 1950s TV series The Army Game, the actor Michael Medwin, who has died aged 96, also enjoyed success in other areas of show business across seven decades.

He began his career in the theatre and co-scripted several of the films in which he appeared, including My Sister and I (1948), Children of Chance (1949) and the musical Scrooge (1970), in which he was nephew to a Scrooge played by Albert Finney. He founded a production company, Memorial, with Finney and produced several British classics, including Lindsay Anderson’s If… (1968).

Memorial’s first film, Charlie Bubbles (1968), directed by Finney, was a quirky comedy drama about a novelist returning to his northern roots. It featured a miscast Liza Minnelli and, because of its fragmented narrative, enjoyed only modest commercial success. However, it boasted fine technical and artistic credits that characterised the company’s subsequent productions.

They moved on to the spirited and subversive If…, co-produced and directed by Anderson. This powerful study of rebellious youth became a key movie of the decade and Memorial’s most significant production. Others included Bill Naughton’s Spring and Port Wine (1970), which had originated on radio, and Stephen Frears’s spoof thriller Gumshoe (1971), a stylish success that starred Finney as the eponymous detective.

Medwin again collaborated with Anderson on the satire O Lucky Man! (1973) and a year later worked in the US co-producing and playing a cameo in Ivan Passer’s uneven comedy, Law and Disorder. There was a gap until Memoirs of a Survivor (1981), an ambitious attempt at filming Doris Lessing’s novel. It failed commercially and proved to be Memorial’s swansong.

Medwin was born in London, and adopted by Dr Mary Jeremy and Ms Clopton-Edwards, whom he described as “two maiden aunts”. He was educated at Canford school, Dorset, before training for the theatre at the Italia Conti school in London, and made his acting debut in Where the Rainbow Ends at the New theatre in 1940.

After a busy period on stage, he had a couple of walk-on parts in the films Piccadilly Incident (1946) and The Root of All Evil (1947), before the director Herbert Wilcox cast him as Edward Courtney in the glamorous and highly successful The Courtneys of Curzon Street (also known as Katy’s Love Affair, 1947). Medwin was up and running in the heyday of postwar British cinema, notching up around 20 roles in five years.

They varied from the guileless Just William’s Luck (1948) and Woman Hater (1948) to Cavalcanti’s formidable For Them That Trespass (1949) and Thorold Dickinson’s The Queen of Spades (also 1949). Medwin played a spiv in Night Beat (1947), a cabby in Forbidden (1949), an elderly doctor in Anna Karenina (1948) and, alongside his fellow youngsters Roger Moore and Christopher Lee, was a marquis in Trottie True (also known as The Gay Lady, 1949).

Despite specialising in brash roles, he proved exceptionally versatile, and Michael Caine, who appeared with him in the war movie A Hill in Korea (1956), wrote: “I was amazed when I met him to discover that he had a very upper-crust accent. Cockney is a hard accent to do and he did it brilliantly.” By the time that film came out, Medwin was playing leading roles, but his attitude to work remained modest and he said later: “I’ve never been ambitious. Being a character actor in a high-risk business can be difficult, so it was a joy to be employed. I had no Everest to climb.”

The parts grew better, including one as the sparky British soldier in Four in a Jeep (1951), an intriguing portrait of the “four-way divide” in postwar Vienna. He was the title character in the spy story The Teckman Mystery (1954), and landed the best role of his career in The Intruder (1953), adapted by Robin Maugham from his novel Line on Ginger. Medwin was Ginger, a former soldier caught by his commanding officer (Jack Hawkins) while burgling the officer’s home. It was an intelligent snapshot of postwar Britain, with Medwin brilliant as the sympathetic, yet gutsy, unemployed “villain”, and a precursor to the social movies with which he and Finney would later be involved.

Until then, Medwin remained busy, acting in the thriller Bang, You’re Dead (AKA Game of Danger, 1954) and Joseph Losey’s bizarre short A Man on the Beach (1956), and giving valuable support to Max Bygraves in Charley Moon (1956), Frankie Vaughan in The Heart of a Man (1959) and Tommy Steele in The Duke Wore Jeans (1958). He was also on call for the Doctor and Carry On series and ubiquitous war films.

He had made his television debut as a boxer in Kid Flanagan (1948). In The Army Game (1957-58), he was Springer, the ringleader to four privates who regard national service as a licence for anarchy. In the series The Love of Mike (1960) he starred as the jazz musician Mike Lane, and in Shoestring (1979-80), he was the radio station boss Don Satchley to Trevor Eve’s phone-in detective Eddie Shoestring. He was in the Mel Smith comedy series Colin’s Sandwich (1988), the spy miniseries The Endless Game (1989), which starred Finney, and played the Red King in a TV version of Alice Through the Looking Glass (1998).

Later film roles included a theatre surgeon in Anderson’s Britannia Hospital (1982), a doctor in the Bond saga Never Say Never Again (1983), a producer in Hôtel du Paradis (1986) and a speechmaker in The Duchess (2008).

He had appeared in many theatre productions, including Man and Superman, Joe Orton’s What the Butler Saw and Noises Off. In 2010, playing Paris, he was the oldest cast member of a Bristol Old Vic production of Romeo and Juliet that starred the 76-year-old Siân Phillips as Juliet and Michael Byrne, in his late 60s, as Romeo. In 1988 he was a co-founder of David Pugh Ltd, a London and Broadway theatre production company and he remained a director well after announcing his retirement from acting in 2008.

He was appointed OBE in 2005 for services to drama.

His marriage to Sunny Sheila Back ended in divorce in 1971.

• Michael Hugh Medwin, actor and producer, born 18 July 1923; died 26 February 2020