Tom Vallance’s “Independent” obituary:

Born Lewis Frederick Ayre in 1908, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, he studied medicine at the University of Arizona but was more interested in music, playing banjo in the college orchestra. While playing with a dance band at Cocoanut Grove in Hollywood, he was spotted by the talent scout Paul Bern and after a minor role in The Sophomore (1929) was signed by MGM to play opposite Garbo in her last silent film, The Kiss (1929).

Lewis Milestone, about to direct All Quiet on the Western Front at Universal, had decided to cast Douglas Fairbanks Jnr in the lead, though Bern suggested Ayres for the role. The film’s dialogue director, George Cukor, shot a test of Ayres (along with other hopefuls) and Milestone saw it on the day that United Artists (who had Fairbanks under contract) informed him that they would not loan their star. Ayres later stated, “Milestone told me time and time again that if I had made the tests earlier I probably never would have been chosen.”

As one of a bunch of schoolboys persuaded by their jingoistic master to enlist in the war, only to become disillusioned as they are decimated in futile military action, Ayres perfectly captured the pain and resignation of innocence betrayed. Asked while on leave to lecture to a group of young students about the glories of war, he makes a tentative start then angrily tells them, “When it comes to dying for your country, it is better not to die at all!”, provoking hisses and boos. Equally memorable is the famous ending, where a sniper’s bullet ends the boy’s life as he reaches from his trench for a butterfly.

Signed to a contract by Universal, Ayres was loaned to Warners to play a feared gangster boss in Doorway to Hell (1930), a monumental piece of miscasting. (James Cagney’s presence in the cast, as one of Ayres’s henchmen, only made the boyishly innocent Ayres look more incongruous.) He made over 20 films, mostly routine fare that slowly eroded his reputation, over the next few years, and in 1936 tried directing with Hearts in Bondage, which was not a success. Now starring in B-movies, he told a reporter, “Hollywood, quick to acclaim, soon washed its hands of me – and the snubs you get sliding down aren’t nearly as pleasant as the smiles going up.”

He was given his first good role in years when George Cukor offered him the part of Katharine Hepburn’s brother in Holiday (1938), a beautiful screen adaptation of Philip Barry’s play and one of the finest of Thirties comedy-dramas. Ayres, who confessed to having “coasted” through many of his previous roles, made his role as a young alcoholic socialite wistfully endearing, though the film belonged to its stars Hepburn and Cary Grant.

The same year MGM cast Ayres in the title-role of a B- picture, Young Doctor Kildare, as an intern working under the guidance and watchful eye of elderly Dr Gillespie (Lionel Barrymore). A great hit, the film started a series, and Ayres was working on his 10th when he was drafted to serve in the Second World War and he refused combat duty on religious grounds.

His career seemed over. Louis B. Mayer fired him and re-shot his scenes with Philip Dorn. Exhibitors refused to book films in which he appeared, pickets appeared outside cinemas that tried to show the Kildare films, and Variety called him “a disgrace to the industry”.

After working in a labour camp, Ayres volunteered for non-combatant duties and served on the battlefront as a medic and chaplain’s aide. Though he had decided to retire from movies, he changed his mind while overseas. “I realised how important movies are to the lives of so many people,” he said.

Restored to favour, he starred opposite Olivia De Havilland in Robert Siodmak’s The Dark Mirror (1946), but later confessed dissatisfaction with his work. “As a psychiatrist investigating twin sisters, one of whom is a murderer, I played it too lightly. My character should have struggled and sweated more. I did too much smiling.”

In Vincent Sherman’s The Unfaithful (1947), a splendid melodrama that effectively reworked Maugham’s The Letter to deal with the subject of wartime infidelity, he was a lawyer who defends Ann Sheridan on a charge of murder and also tries to salvage her marriage to a returning soldier, Zachary Scott.

His next film, Johnny Belinda (1948), won him a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his sincere portrayal of a doctor who teaches a deaf and dumb Jane Wyman how to communicate, though Ayres was not happy with Jean Negulesco as director. “He was artistic and very extroverted, but none of us felt he was on target with the characterisations, so the actors became their own directors. Jane, Charles Bickford, Agnes Moorehead and myself respected each other’s opinions, so after Jane and I did a scene we’d look at Charles and Agnes. If they nodded, we would proceed: if they shook their heads, we’d do the scene again.”

With roles once again becoming scarce, he embarked on a world tour in 1954 to compile a documentary, Altars of the East, which he wrote, produced, narrated and financed. A probing of the frontiers of faith, it started a decade’s study of comparative religion (“the most meaningful thing I have ever done”) and production of several documentaries on the world’s religions. In 1957 he was appointed by the Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, to serve a three-year term on the US National Committee for Unesco.

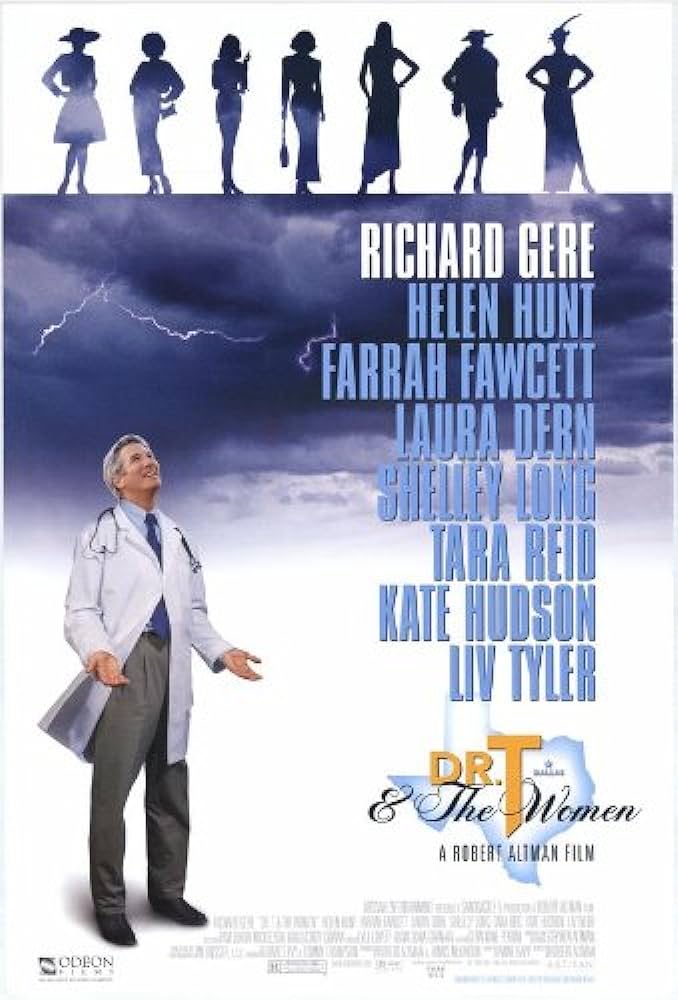

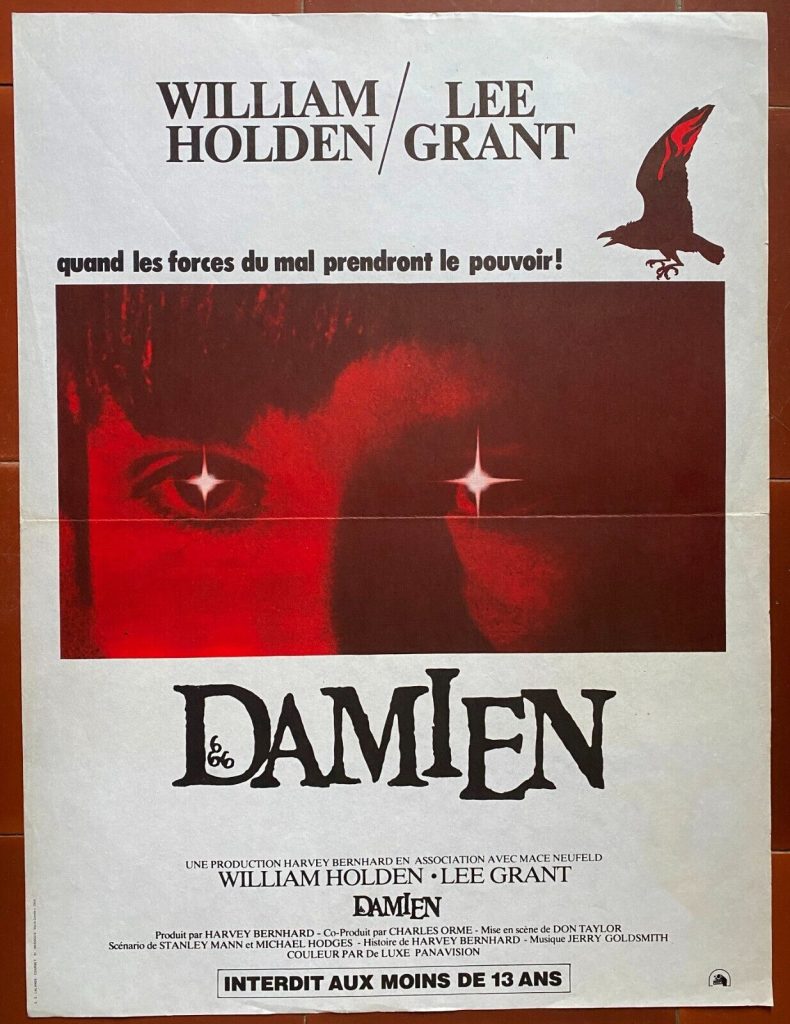

Returning to acting as a character player, he was a frequent performer in television plays and movies, plus occasional big-screen roles, among them Advise and Consent (1962), Battle for the Planet of the Apes (1973) and Damien – Omen II (1978). “I still act occasionally,” he said recently, “but I’m in my eighties and have never had my face lifted, so there aren’t a lot of roles.”

Two early marriages were unsuccessful – to Lola Lane (1931-33) and Ginger Rogers (1933-40) – but in 1964 he married an Englishwoman, Diana Hall, and the day before his 60th birthday she gave birth to their son, Justin.

“If I were young again,” Ayres said, “I don’t think I’d be an actor. I’ve met some wonderful people, and it made many things possible for me, but if I had it all to do over again, my field would be philosophy.”

Lewis Frederick Ayre (Lew Ayres), actor: born Minneapolis, Minnesota 28 December 1908; married 1931 Lola Lane (marriage dissolved 1933), 1933 Ginger Rogers (marriage dissolved 1940), 1964 Diana Hall (one son); died Los Angeles 30 December 1996.

The “Independent” obituary above can also be accessed online here.

TCM overview:

This earnest, boyishly handsome star of the pacifist classic “All Quiet on the Western Front” (1930) was extremely prolific during the 1930s, at first primarily at Universal Studios, and then also at Fox and Paramount. Although a very talented and sensitive actor, Ayres found his early stardom fade during the decade as he was cast in either trivial light comedies which suited his gentle manner or in films which called for tough, streetwise characterizations which didn’t always suit him. He gave an excellent performance, though, as Katharine Hepburn’s drunken brother in George Cukor’s “Holiday” (1938) and enjoyed considerable popularity in a series of Dr. Kildare films at MGM in the late 30s and early 40s. His career faded during WWII after he declared himself a conscientious objector, but he received renewed respect when he served bravely in a non-combat medical capacity.

After the war Ayres was able to resume his career–and his sometimes typecasting as doctors–in such films as “The Dark Mirror” (1946) and “Johnny Belinda” (1948), for which he received a Best Actor Oscar nomination, though he did little acting in film after the mid-50s. He did, however, do notable work as the vice president in “Advise and Consent” (1962) and as a sympathetic resident of the vampire-ridden TV-miniseries town of “Salem’s Lot” (1979). A student of comparative theology, Ayres later produced the religious documentaries “Altars of the East” (1955) and “Altars of the World” (1976), also serving as director of the latter.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.