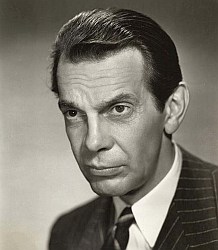

TCM Overview:

Suavely handsome, often tongue-in-cheek leading man of the 1930s and 40s who began his career with a provincial theater company in England. Hayward came to Hollywood in the mid-30s and quickly established a second-rank level of stardom which lasted until the mid-50s. He more than held his own in a wide variety of films; his light touch with cynical, witty banter suited him well in drawing room comedies and romantic dramas (“The Flame Within” 1935, “The Rage of Paris” 1938, “Dance Girl Dance” 1940), but he regularly appeared in detective films and adventures as well. Often cast as somewhat roguish playboys, Hayward played the leading role in Rene Clair’s sterling adaptation of Agatha Christie’s mystery “And Then There Were None” (1945) and was fine in dual roles James Whale’s stylish version of “The Man in the Iron Mask” (1939).

The latter film prefigured the later contours of Hayward’s film career, as his athletic, romantic dash led him to be cast in many medium-budgeted swashbucklers, four of which (including “Fortunes of Captain Blood” 1950 and “The Lady in the Iron Mask” 1952, recalling his earlier triumph) teamed him with Patricia Medina. Hayward was married for a time to Ida Lupino, with whom he co-starred in the Gothic melodrama “Ladies in Retirement” (1941).

Los Angeles Times obituary in 1985:

TIMES STAFF WRITER

Louis Hayward, whose debonair charm and athletic good looks made him one of Hollywood’s most successful swashbuckling heroes of the 1930s and ‘40s, died Thursday at Desert Hospital in Palm Springs.

He was 75 and had spent the last year of his life in a battle against cancer, which he attributed to having smoked three packs of cigarettes a day for more than half a century.

A lifelong performer (“I did a Charlie Chaplin imitation for my mother when I was 6 and never really got over it,” he told friends), Hayward scored his first major screen success with the 1939 film, “The Man in the Iron Mask,” and spent the next decade starring in such adventure films as “The Son of Monte Cristo,” “The Saint in New York,” “The Black Arrow” and “Fortunes of Captain Blood.”

“I also did rather creditable acting jobs as the rotten seed in ‘My Son, My Son,’ and the villainous charmer in ‘Ladies in Retirement,’ ” he said ruefully. “But nobody really cared. They just handed me another sword and doublet and said ‘Smile!’ ”

Born March 19, 1909, in Johannesburg, South Africa, a few weeks after his mining engineer father was killed in an accident, Hayward was taken first to England and then to France, where he attended a number of schools under his real name, Seafield Grant.

He received early training in legitimate theater, appeared for a time with a touring company playing the provinces in England and then took over a small nightclub in London.

“Which is where my career really began,” he said. “Noel Coward came in one night; I managed to talk to him for a time and wound up wriggling into a small part in a West End company doing ‘Dracula.’ ”

He followed with roles in “The Vinegar Tree,” “Another Language” and “Conversation Piece” before going to New York, where a chance acquaintance with Alfred Lunt led to a role in the Broadway play, “Point Valaine,” for which he won the 1934 New York Critics Award.

His first Hollywood efforts in “The Flame Within” and “A Feather in Her Hat” were moderately successful, moderately well-received and almost instantly forgotten.

But then came the 1936 role of Denis Moore in “Anthony Adverse,” and studio officials began talking about stardom.

The dual role of Louis XIV and Philippe in “The Man in the Iron Mask” established Hayward as a swashbuckler and was followed by major roles in “And Then There Were None,” “The Duke of West Point” and similar vehicles.

Hayward, who had become a naturalized U.S. citizen the day before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, served three years in the Marine Corps during World War II, winning the Bronze Star for filming the battle of Tarawa under fire.

Formed Own Company

Returning to films after the war, he formed his own film company and was one of the first stars to demand and get a percentage of the profits from his pictures, which included “Repeat Performance,” “The Son of Dr. Jekyll,” “Lady in the Iron Mask,” “The Saint’s Girl Friday,” “Duffy of San Quentin” and “The Lone Wolf,” which he subsequently turned into a television series, playing the starring role in 78 episodes in the 1960s.

Hayward left Hollywood in the late 1950s to appear in a British television series, “The Pursuers,” returning for television appearances in “Studio One” and “Climax” anthology shows and returning to the stage as King Arthur, opposite Kathryn Grayson, in a Los Angeles Civic Light Opera production of “Camelot” in 1963.

His first two marriages, to actress Ida Lupino and to socialite Margaret Morrow, ended in divorce.

Hayward, who had lived in Palm Springs for the last 15 years, is survived by his wife, June, and a son, Dana. At his request, a family spokesman said, no funeral was planned.

.jpg)