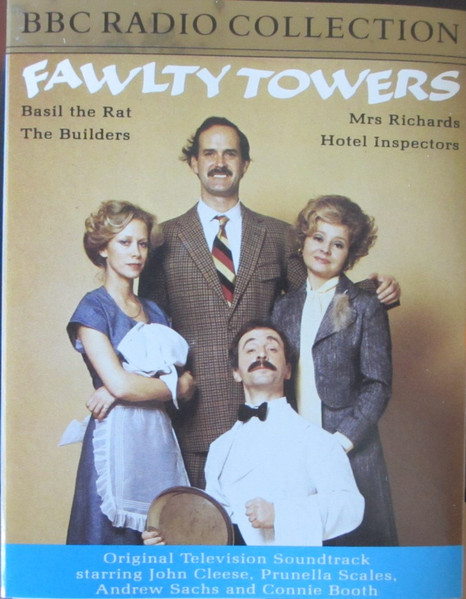

Prunella Scales was entitled to feel miffed that her portrayal of Sybil in the television sitcom Fawlty Towers put her so firmly in the public mind as a comedy actress. Most of her career had, after all, been spent doing serious drama, from Shakespeare to Chekhov, Beckett, Pinter and Bennett.

Sybil was nonetheless a superb comic creation. A small yet domineering figure with a towering hairdo and a raucous laugh, she was the perfect foil to John Cleese’s manic, snobbish Basil, the Torquay hotelier who hated his guests. Although Sybil was intimidating, she was also flirtatious and gossipy, especially on the phone — “Oooh, I know” — and, crucially, she was socially below Basil, which was not what Cleese and Connie Booth, his co-writer, had envisaged but rather what Scales suggested.

Their on-screen chemistry was perfect, with each as long-suffering as the other. While Basil would address Sybil in a faux romantic way, calling her “my little nest of vipers”, she would say: “You never get it right, do you? You’re either crawling all over them [the guests], licking their boots or spitting poison at them like some benzedrine puff adder.” In any event, her short, sharp cry of “Basil” was all it ever took to stop him in his tracks. He was terrified of her. “I don’t feel sorry for him,” she said of her character. “I feel sorry for her, being married to a lunatic.

Scales based the character of Sybil on someone she met when she was a child — a hotelier with an ingratiating manner who spent all day painting her nails. The media were always disappointed to meet Scales in real life and see that she was nothing like Sybil, not least because she had a rather patrician way of speaking.

Fawlty Towers ran for only 12 episodes spread over four years, 1975 to 1979, but the memory of it never faded. Indeed, many years later, the British Film Institute ranked it first on a list of the 100 greatest British television programmes. While Scales accepted that the role overshadowed her acting career, she did not think this was necessarily a bad thing.

“In this business, you are lucky if you become associated with a single role because then people are curious to find out what you will do next.” That said, the main reason she went into acting was “the chance to play people more interesting than me

Prunella Margaret Rumney Illingworth was born in Sutton Abinger, Surrey, in 1932. Her father, John Illingworth, was a sales manager for Tootal, the cotton firm, and her mother, Catherine Scales, was a professional actress. Her unusual first name came from a play, Prunella, by Laurence Housman and Harley Granville-Barker, in which her mother had acted. Her friends called her Pru.

“I’m so grateful to my parents because they were really very hard up,” she recalled in later life. “During the war we — my brother, Timothy, and I — were evacuated to a little village in Devon and my mother kept the two of us and a friend on £8 a week. This is ‘I was born in a shoe box on the M1’ territory, but my father only ever had what he earned.”

Her parents were a bit eccentric, she reckoned, because they sold the only house they ever owned for fear it would get bombed and through friends rented a farmhouse 35 miles from Hyde Park Corner. “There was no gas, electricity or water but we had lots of books. When we went to other people’s houses, we used to enjoy the electric light.” She walked through the woods every day and caught a bus to Dorking North station to get to school at Dulwich.

Her first ambition was to be a ballet dancer but there were no ballet classes where she lived and by the age of eight she wanted to be an actress. She attended Moira House, a progressive girls’ boarding school in Eastbourne, East Sussex, where she excelled academically, getting eight As in her school certificate, and acted in many school productions

In 1949, she won a scholarship to the Old Vic drama school in London and, to start with, she struggled. She was barely 17 and unworldly, stood only 5ft 3in and sported pigtails and thick glasses. However, she battled through and on leaving joined the Bristol Old Vic as an assistant stage manager. Her first professional role was an elderly cook in Jean Anouilh’s Traveller Without Luggage.

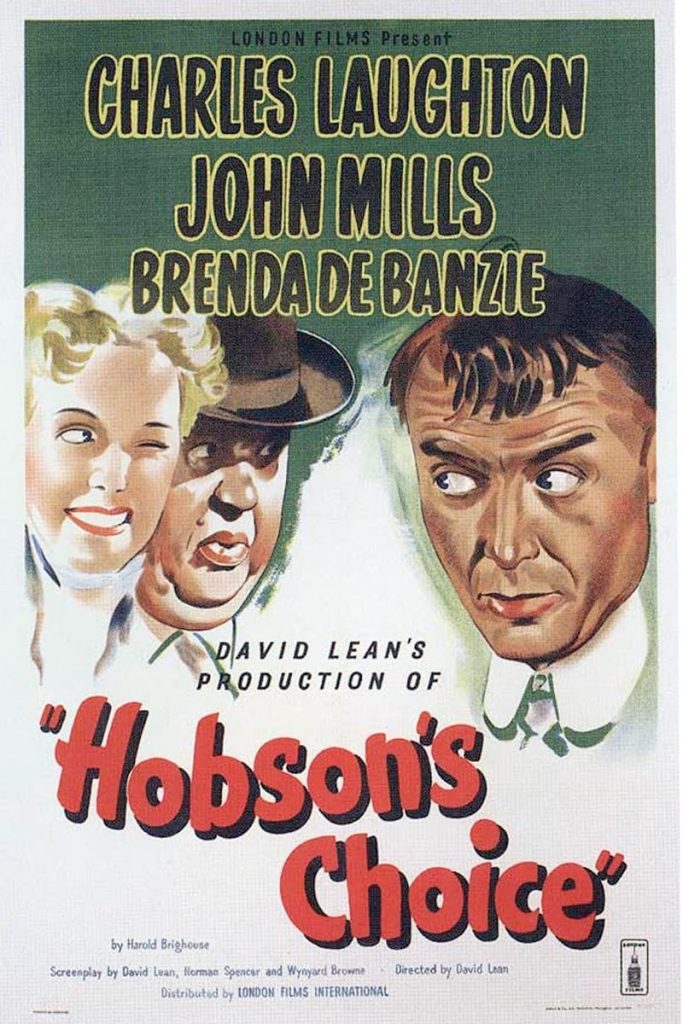

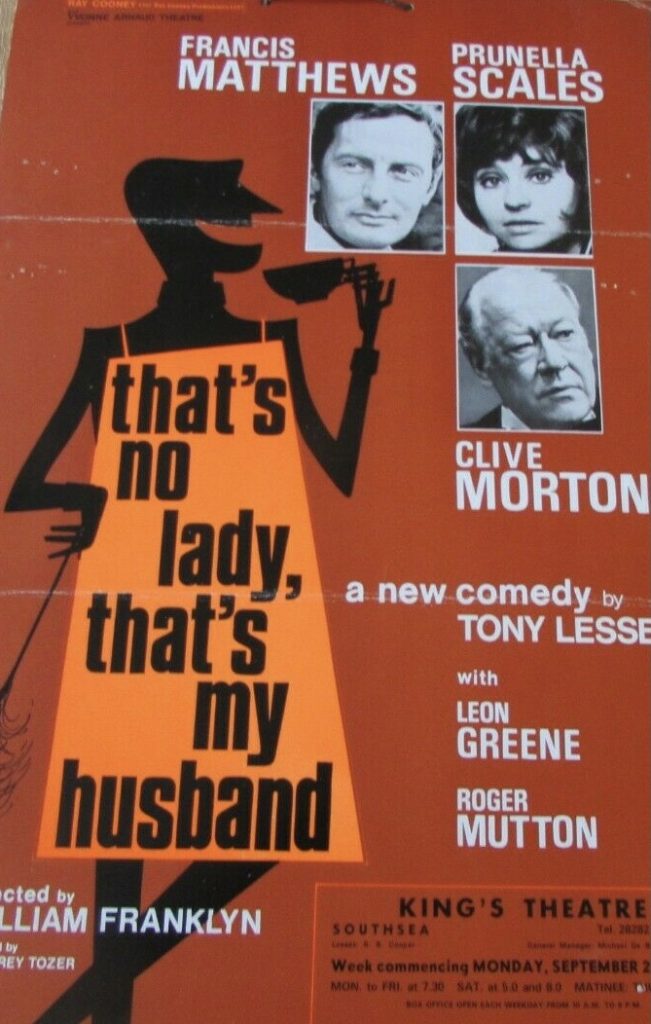

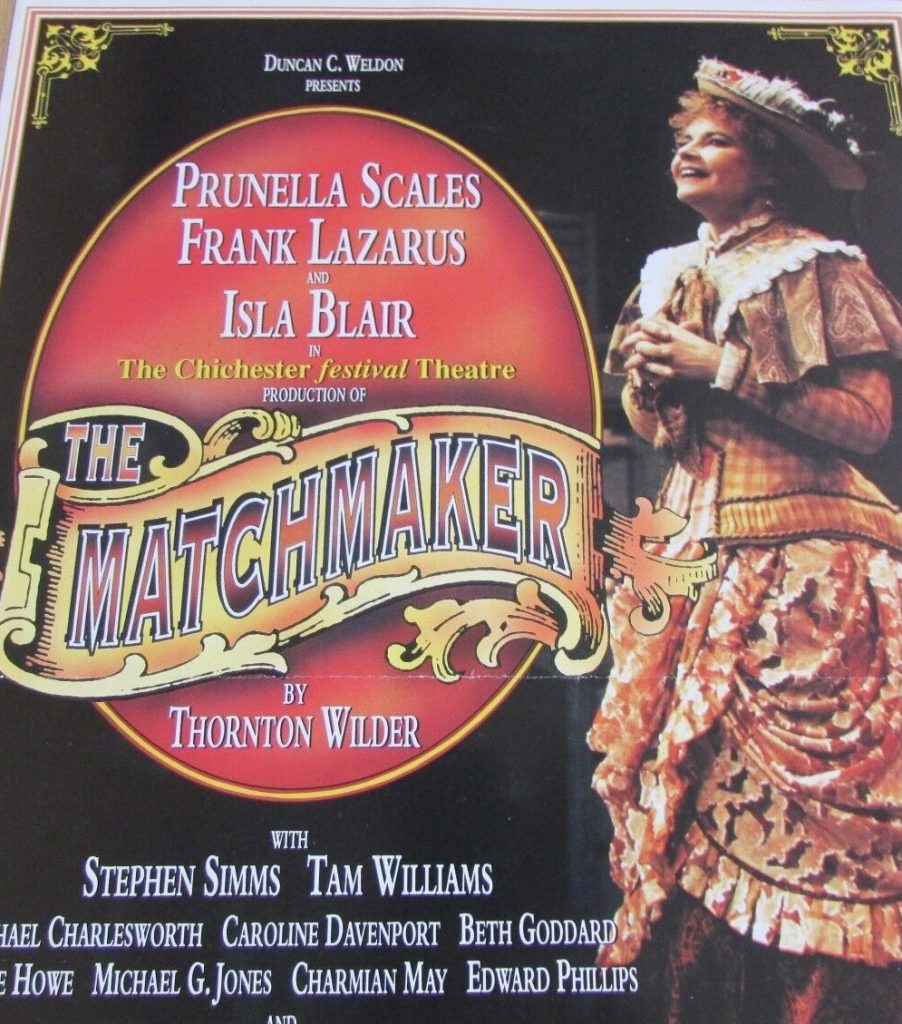

She was soon given her first film, Laxdale Hall, playing a Scottish schoolmistress, and in 1952 she made her television debut as Lydia Bennett inPride and Prejudice. Three years later, she made her West End debut as the romantic juvenile Ermengarde in Thornton Wilder’s The Matchmaker, directed by Tyrone Guthrie.

It ran for nine months in London before transferring to the US, playing in Philadelphia, Boston, Washington and finally on Broadway. While in New York, she attended acting classes under Uta Hagen at the Herbert Berghof Studio, which helped to build her confidence after her unhappy experience at the Old Vic School. Then the teachings of Stanislavsky, the inspiration for the American Method school, had meant little. Now they made sense.

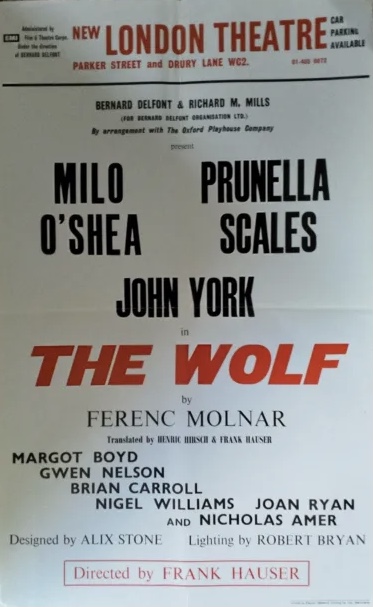

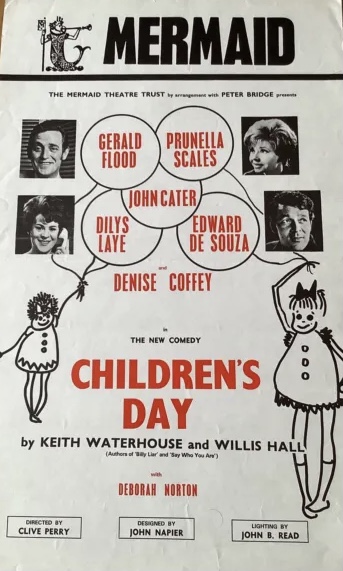

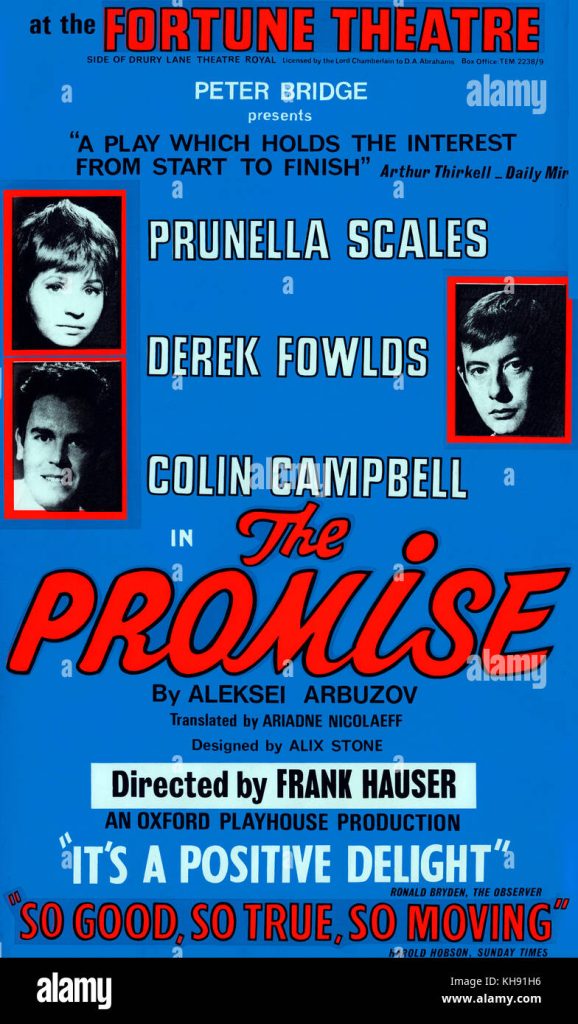

After playing small parts during the 1956 Shakespeare season at Stratford-upon-Avon, she joined the Oxford Playhouse, where she blossomed under a sympathetic director, Frank Hauser, and played the pupil in the first English production of Eugène Ionesco’s The Lesson.

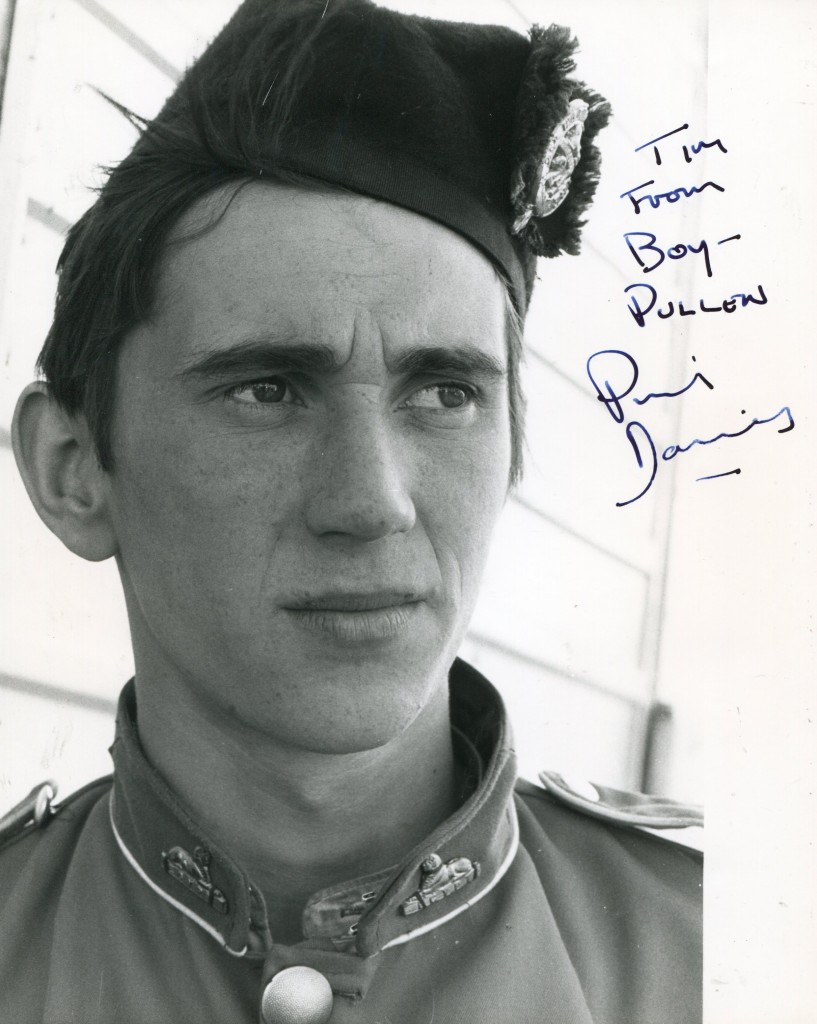

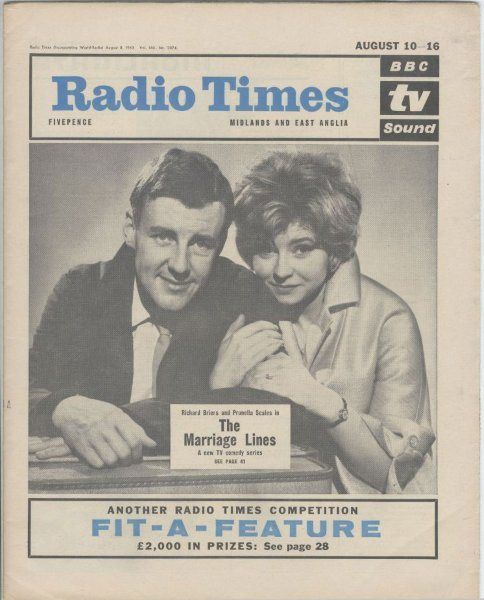

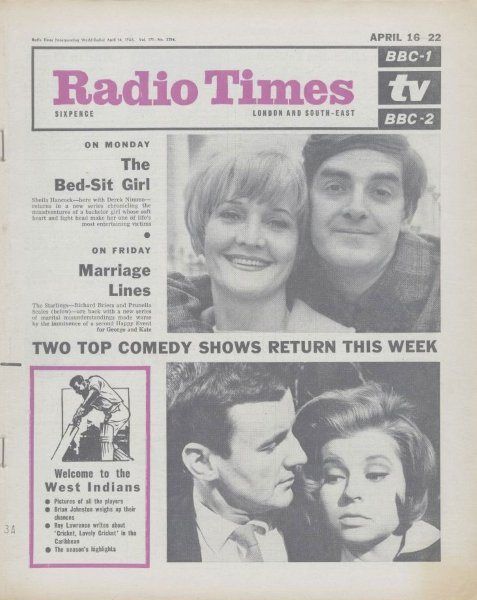

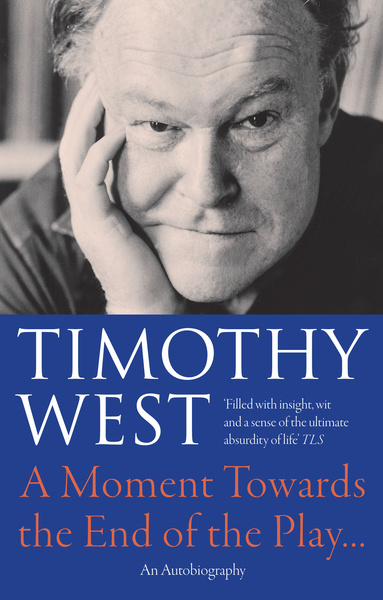

On television, she was a bus conductress in two episodes of Coronation Street before, in 1963, becoming a household name through the BBC comedy Marriage Lines. She and Richard Briers played newlyweds negotiating the pitfalls of early married life. She was keen to be the perfect wife, but managed to burn the dinner and resented being stuck at home while her husband joined his pals in the pub. There were frequent rows, but good nature prevailed. Towards the end of the show’s three-year run, Scales, who had married the actor Timothy West, became pregnant and her character followed suit.

Theirs was the happiest of unions, both professionally and personally, and would last for 61 years. Scales and West had two sons, Joseph, a translator and teacher, and Samuel, who became a distinguished actor and director in his own right. “My parents warned me it was a difficult profession,” Samuel West once said. “They were saying you are going to be unemployed, you are going to have to do shit work just to keep solvent, you are going to be associated with types or brands or characters that people will expect you to be — like my mother in the case of Sybil — and you will experience mild euphoria and pleasant triumphs and deep loneliness and despair.” Scales is survived by her sons and a stepdaughter, Juliet, from West’s previous marriage.

Such may have been the disadvantages of a husband and wife being in the same profession, but the marriage, Scales found, got easier with time. “When the children were young, I did have a lot of time when I was getting much less work, and I was a bit discontented. I think, to do him justice, Tim was equally worried. But, on the whole, over the years, we’ve had the same amount of work and that’s a great blessing

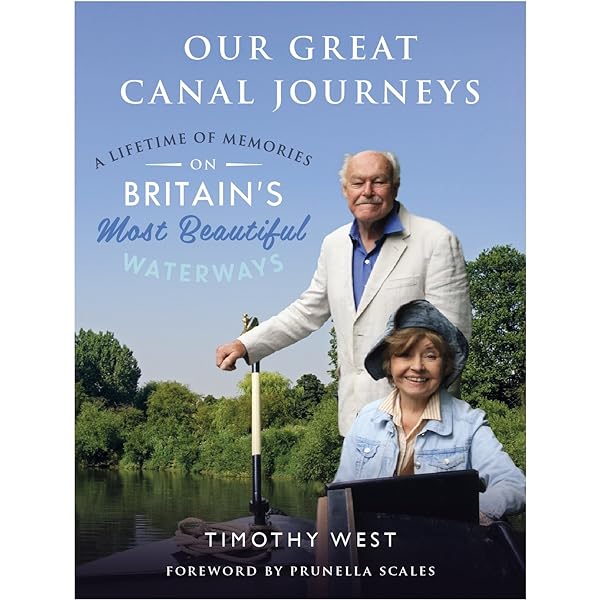

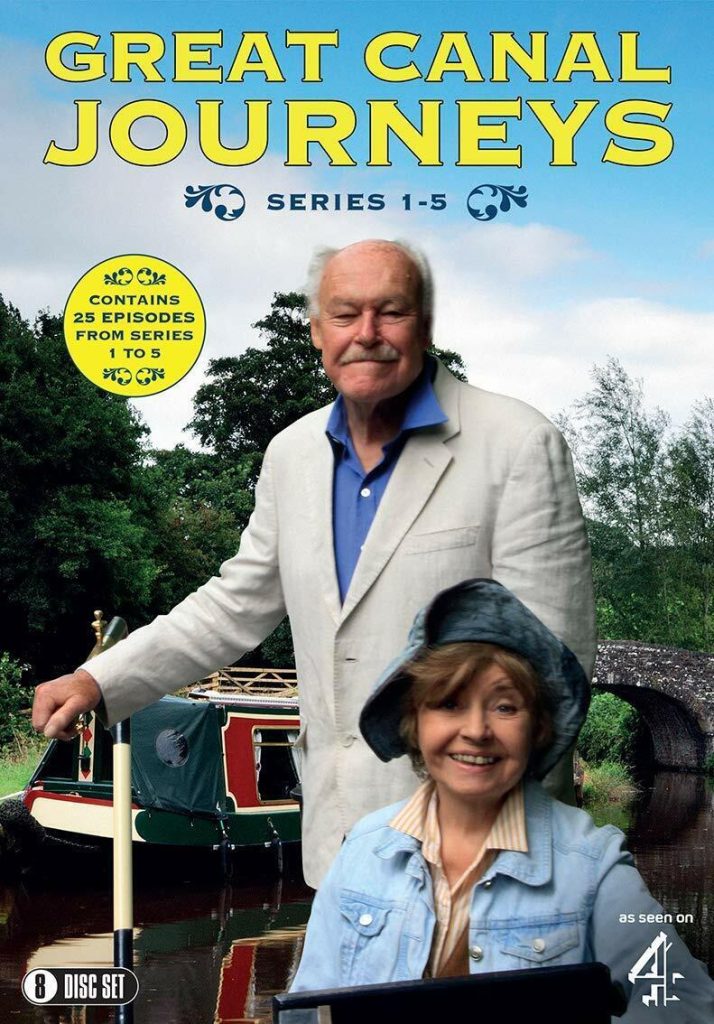

They had a shared hobby throughout their marriage — narrowboating. “The boys got lovely and tired opening locks and went to bed early, so in the evenings their parents could play Scrabble and chess and make love. I cook better on the boat than I do at home: there’s no telephone, no TV — it’s been the perfect resource for us.” She had always preferred being in the countryside to the town — she was the president of the Campaign to Protect Rural England from 1997 to 2002 — and canals afforded her a perfect means by which she could be close to nature.

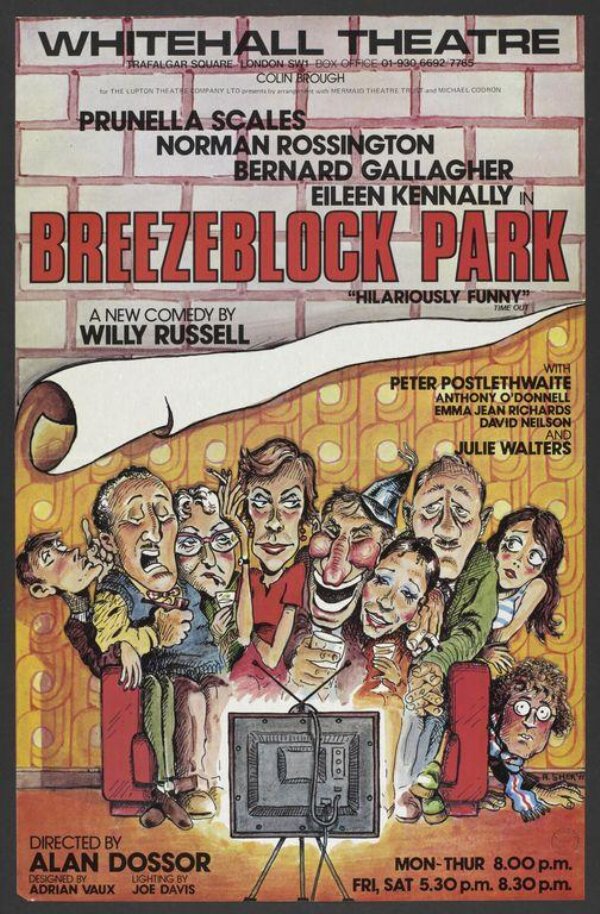

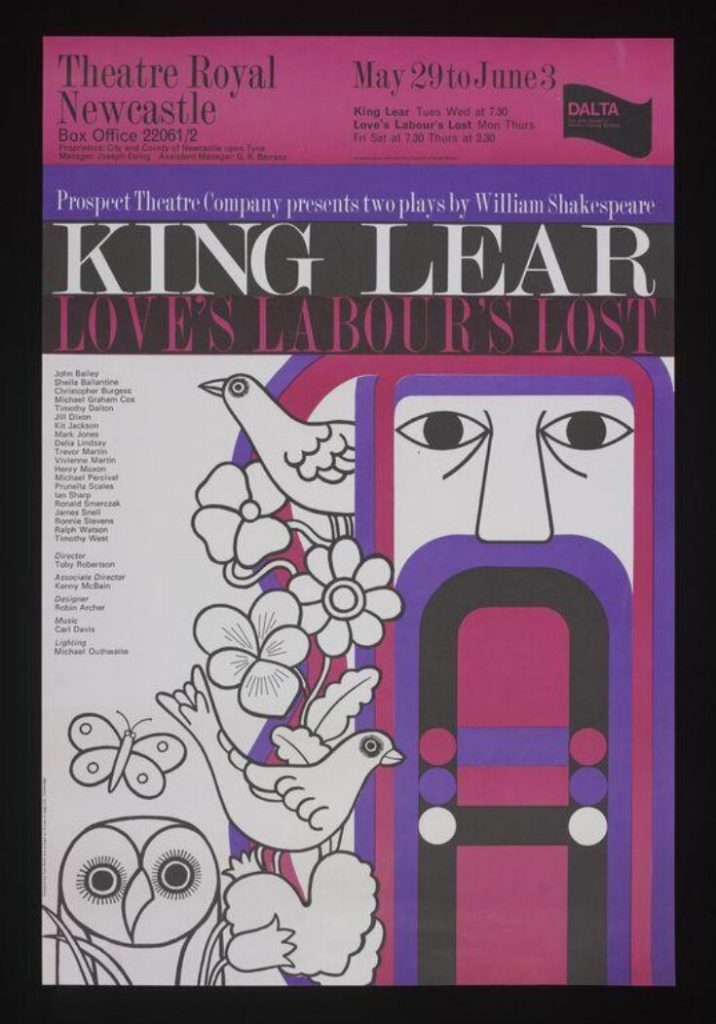

Despite the success of Marriage Lines, Scales was little seen on television until Fawlty Towers came along almost a decade later, and in the meantime she concentrated on the stage. At the Nottingham Playhouse under Richard Eyre, she played Katherine in The Taming of the Shrew and made her bow as a director on Major Barbara. She directed many other productions, including Uncle Vanya and Alan Bennett’s Getting On, both starring her husband.

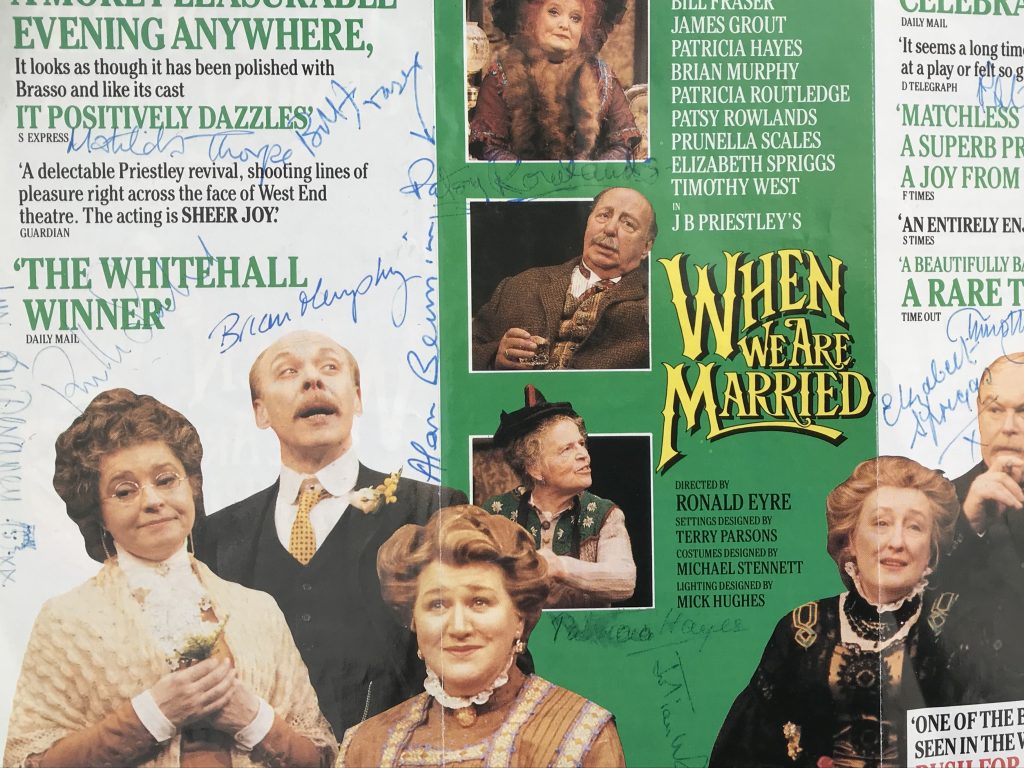

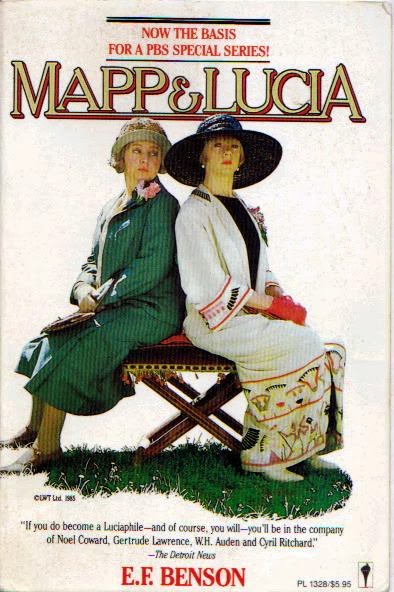

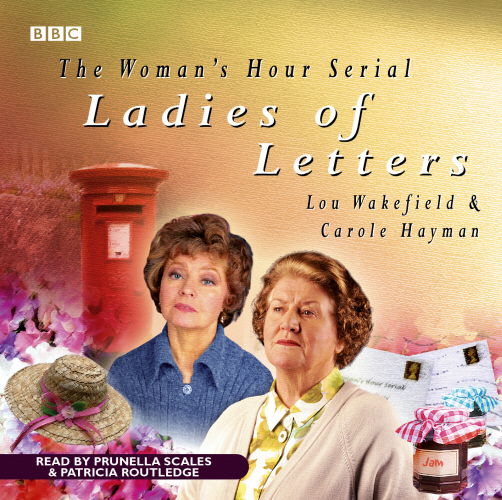

Immensely hard-working and a perfectionist, Scales always started from the character’s background, who she was and where she came from. If she got the accent and the speech pattern right, much else would fall into place. On television, in 1985 she was felicitously teamed with Geraldine McEwan as the country ladies trying to outdo each other in Mapp & Lucia, from the novels by EF Benson. Another television success was Simon Brett’s gentle comedy After Henry, which started on Radio 4 in 1985 and was taken up by ITV where it ran for four series. Scales was a widow who shared her house with her manipulative mother and precocious teenage daughter. The following year she raised eyebrows when she appeared nude in an episode of Unnatural Causes, in which she plays a wife who cooks her husband. She was, she said, pleased to receive only one letter of complaint, from a vicar in Derbyshire.

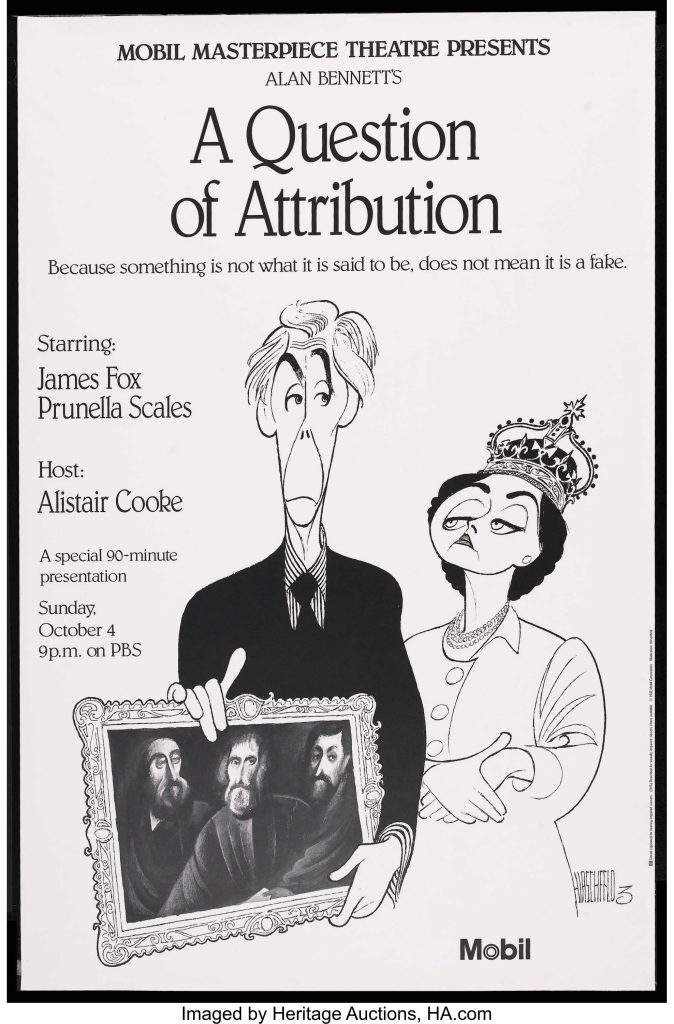

In 1988, she played the Queen in Alan Bennett’s A Question of Attribution at the National Theatre. She worked hard on capturing the Queen’s voice, look and bearing and created an astonishingly lifelike performance well clear of caricature. She was appointed CBE in 1992. At the investiture, the Queen, remembering her portrayal at the National, said: “I suppose you think you should be doing this.”

On the other half of an Alan Bennett double bill, Scales played the actress Coral Browne in An Englishman Abroad, visiting the spy Guy Burgess in Moscow. She looked nothing like Browne but clever acting took her through

One of the roles for which she was best known was the domineering Dotty in television commercials for Tesco, with Jane Horrocks as her daughter. She used the money to subsidise her less-well-paid stage work and had no qualms: “I tell my critical socialist chums that it is my way of obliging industry to fund the arts.” She always voted Labour and was an active supporter of the party, appearing in general election broadcasts in 2005 and 2010. It was a subject upon which she was prone to get exercised. “I wish I were more effective,” she once said. “The Labour Party has lost so many elections one fears that the support of actors doesn’t help them. We get to one ward meeting in 84 and try to drive people to the polls at election time. But we’re stigmatised as the chattering classes.”

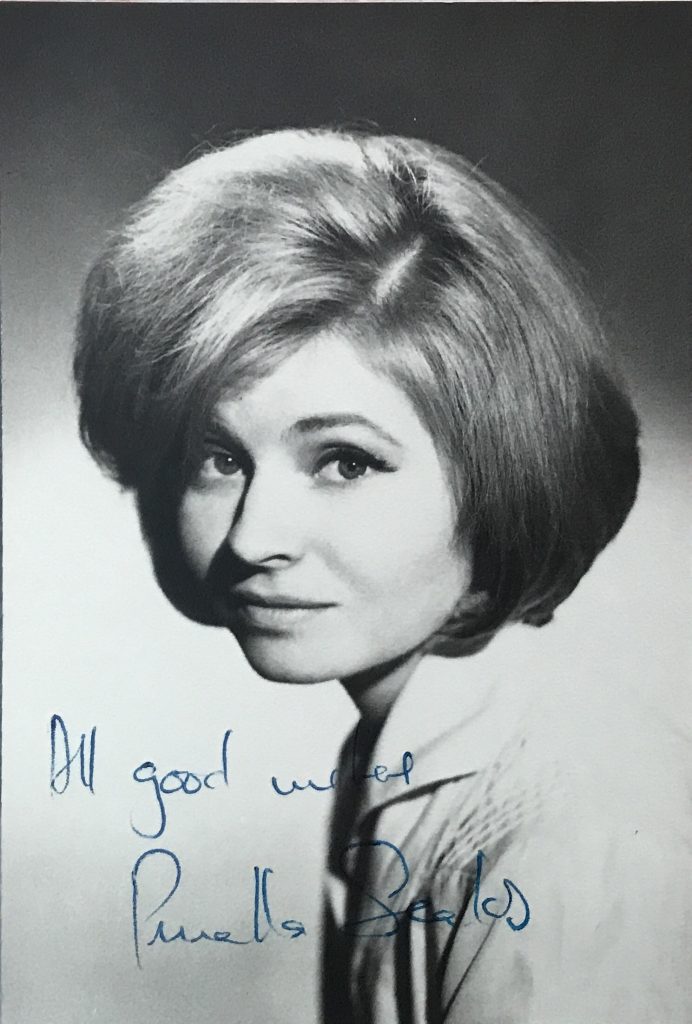

Though she claimed she was never beautiful or even pretty in her youth, Scales was blessed with a youthful appearance that lasted well into older age. This she attributed to her genes, because her mother and father had been the same. She did admit, however, that she had the bags under her eyes done in 1978, “and would do it again if it became necessary”.

In 2014, West (who died last year) announced that his wife had vascular dementia and the couple discussed coping with the disease on a Radio 4 programme with Joan Bakewell. Two years later, they appeared together in Great Canal Journeys for Channel 4. Viewers were touched by West’s attentiveness and devotion and it soon became apparent that this was about something other than a canal journey: it was a meditation on a long and successful marriage drifting to a close. “She can’t remember things very well,” West said, “but you don’t have to remember things on the canal. You can just enjoy things as they happen — so it’s perfect for her.”

Prunella Scales CBE, actress, was born on June 22, 1932. She died on October 27, 2025, aged 93