Anita Harris had a neat reputation as a ballad singer when she also began an acting career on film. She was born in Somerset in 1942. She was part of the Cliff Adam Singers and made several television appearances on British television with the group. She then began a solo singing career and in 1967 has a massive hit with “Just Loving You”. In thelate sixties she became part of the “Carry On” group and starred in “Follow that Camel” and “Carry On Again Doctor”. She still continues to appear on stage and concert halls in Britain. Interview with “Express Newspapers” can be read here.

Anita Harris. Wikipedia.

Anita Harris was born in 1942 and is an English actress, singer and entertainer.

Harris sang with the Cliff Adams Singers and had a number of chart hits in the 1960s. She appeared in the Carry On films Follow That Camel (1967) and Carry On Doctor(1968).

Harris was born in Somerset; her family moved from Midsomer Norton to Bournemouthwhen she was seven. She won a talent contest at the age of three. However, it was her penchant for figure skating which led to her performing career, she began skating at the neighbourhood rink, eventually becoming a regular at the Queens Ice Rink in London. Seen by a talent scout shortly before her sixteenth birthday, she was offered a chance to skate in Paris or to travel to Las Vegas where she would be a dancer in a chorus line. She accepted the latter, danced at the El Rancho Hotel in Las Vegas. We did three shows a night and on the 12th night, we had the night off”, she said years later.

On returning to the UK, she performed in a vocal group known as the Grenadiers and then spent three years with the Cliff Adams Singers.She was still in her teens when John Barry’s manager, Tony Lewis, offered her a recording contract by EMI and made her first recordings with the John Barry Seven — a group which was a successful chart act. This first single, a double A-side of “I Haven’t Got You”, written by Lionel Bart and “Mr One and Only”, did not reach the charts.

Subsequent to their meeting, when they both auditioned for a musical revue, Mike Margolis and Harris formed a personal and professional relationship marrying in 1973. He became her manager and wrote the songs which served as her second and third singles: “Lies”/”Don’t Think About Love”(Vocalion, September 1964) and “Willingly”/”At Last Love” (Decca, February 1965).

In January 1965 she performed at the San Remo Music Festival. Her duet with Beppe Cardile, “L’amore è partito”, failed to reach the finals but even to participate in such a star-studded event augured well for her stardom. She made her label debut for Pye Records with the May 1965 release “Trains and Boats and Planes“, although rival versions by both the song’s composer Burt Bacharach (with vocals by the Breakaways) and Billy J. Kramer & the Dakotas eclipsed her recording. She had four subsequent releases on Pye, including the only evident recording of the Burt Bacharach/ Hal David composition “London Life”.

In 1966, she moved to CBS Records where her debut release was also her debut album: Somebody’s in My Orchard. Her chart breakthrough came in the summer of 1967 with the single “Just Loving You“, a Tom Springfield composition which singer Dusty Springfield had suggested that Tom (her brother) give to Harris after Dusty and Harris had performed on the same episode of Top of the Pops.

Recorded at Olympic Studios in a session produced by Margolis and featuring harmonica virtuoso Harry Pitch, Just Loving You” had been released in January 1967 but did not reach the UK Top 50 until 29 June 1967.[10] Even after peaking at No. 6 on 26 August 1967 “Just Loving You” remained in the UK Top 40 until the end of the year, and was reported to have accumulated UK sales of 625,000 in six months. Besides charting at No. 18 in Ireland, “Just Loving You” was a Top Ten hit in South Africa where sales reached 200,000 copies. The disc was released in September 1967 in the United States where it rose to No. 20 on the “Easy Listening” chart in Billboard and approached the mainstream Pop “Hot 100” chart. It rose no higher than No. 120 on the “Bubbling Under” chart. In January 1968 Harris made her only appearance on the UK album chart when her Just Loving You album reached No. 29.

The sustained interest in “Just Loving You” predicated a mild chart impact for her follow-up single “The Playground”, released in September 1967. This reached its chart peak of No. 46 by 28 October 1967, the same week “Just Loving You” (which had dropped out of the Top 20 at No. 21) returned to the Top 20 for three more weeks. However she did score a substantial hit with her 5 January 1968 release, a remake of the standard “Anniversary Waltz“, which spent eight weeks in the UK Top 40, peaking at No. 21.

After just missing the UK Top 50 with the single “We’re Going on a Tuppenny Bus Ride” (released 17 May 1968), she made her final chart appearance with her rendition of “Dream a Little Dream of Me“. Released on 26 July 1968, her single version peaked in the UK Top 50 at No. 33,[10] whilst the Mama Cass Elliot version peaked at No. 11.

A third album, Cuddly Toy, was released in 1969.

Since 1961 she has made numerous television appearances, mostly as a performer, occasionally as an actress, and her few film roles included a cameo as a casino singer in Death Is a Woman (1966) and co-starring roles in the comedy films Follow That Camel (1967) and Carry On Doctor (1968). Harris gained her role in the latter film while working in a revue Way Out in Piccadilly with Frankie Howerd. Backstage, he introduced her to the producer and director of the series resulting in the decision to cast Harris as well as Howerd.[2][4] In December 1970, Thames Television debuted the children’s TV series Jumbleland which she co-produced and in which she starred as Witch Witt Witty.

Harris worked with magician David Nixon for eight years in the 1970s.[4] She appeared on the Morecambe and Wise Show in 1971 and 1973.[5] In 1981 she was in the line-up for the Royal Variety Performance, singing “Burlington Bertie” This performance she reprised at the Queen Mother’s 90th Birthday celebration at the London Palladium, in 1990, in the presence of the Queen, Princess Margaret and the Duke of Edinburgh in a large company of artistes presenting music hall, featuring many well known TV and stage personalities. That same tribute to the star she had presented several times on the BBC’s variety show, The Good Old Days. She was the subject of This Is Your Life in 1982 when surprised by Eamonn Andrews at London’s Talk of the Town. She was still appearing on television up to 2001, in particular Boom Boom: The Best of the Original Basil Brush Show, French & Saunders and Bob Monkhouse: A BAFTA Tribute.[5]

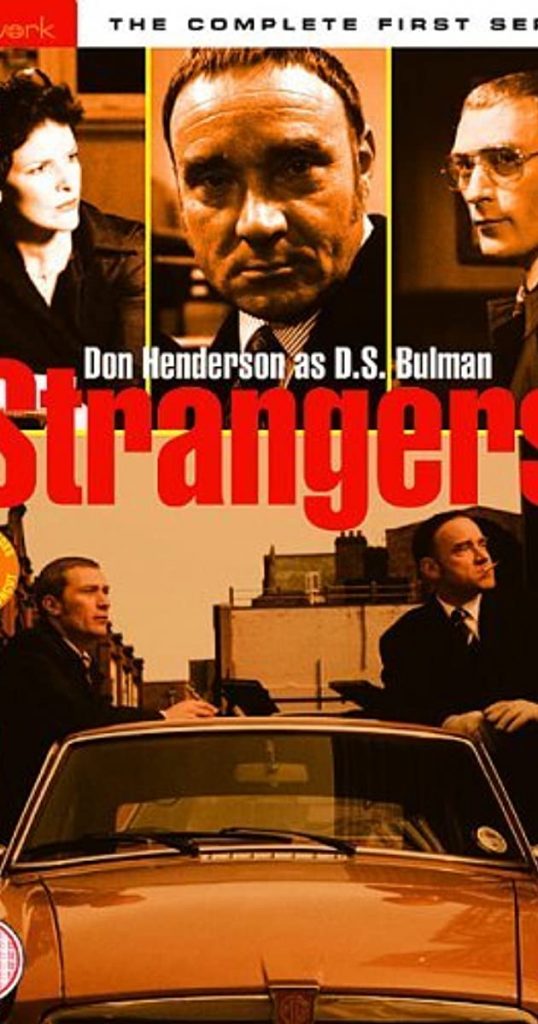

From the early 1970s, Harris toured in several editions of her one-woman stage show which, as Anita Harris in the Act!, was broadcast in 1981. It was essentially a recording of her performance at the Talk of the Town. In 1982 she was named Concert Cabaret Performer of the Year by the Variety Club of Great Britain. Whilst a frequent star of pantomime over the years, she made a debut in legitimate theatre in 1986 when she assumed the role of Grizabella in the West End production of Cats for a two-year tenure,[11] with subsequent credits including Bell, Book and Candle, Deathtrap, Seven Deadly Sins Four Deadly Sinners, Verdict and the stage dramatisations of House of Stairs and My Cousin Rachel. Additionally she co-starred with Alex Ferns, Will Thorp, Colin Baker and Leah Bracknell in the UK tour of the stage adaptation of Strangers on a Train in 2006. She portrayed Gertrude Lawrence in G and I at the New End Theatre in the spring of 2009. In 2010 she starred with Brian Capron in the UK national tour of Stepping Out; having previously played the leading role of Mavis, she now took on the role of Vera. She toured with a new one-woman stage show: An Intimate Evening With Anita Harris in 2013 and appeared in a production of the Emlyn Williams play A Murder Has Been Arranged at the Grand Theatre, Wolverhampton in July 2013 and at Malvern Festival Theatre in August of that year.

In 2014, Harris appeared in a lead guest role in the prime-time BBC drama, Casualty . She continues to perform with her band around the country, including at the Royal Albert Hall, London. She performed in pantomime over Christmas 2014-15 by appearing as the wicked Baroness in a production of Cinderella at the Grand Opera House in York. “I’ve played Aladdin, Jack and Dick Whittington and Robinson Crusoe. I’ve loved playing principal boy and I’m sorry that boys are now playing that role”, she told a York press meeting at the time.

On 12 January 2015, The Mail on Sunday reported that Anita Harris and her husband and manager Mike Margolis were, or were about to be, declared bankrupt by HM Revenue and Customs over historic tax arrears of £14,000 and £25,000 respectively.[13] The bankruptcy order of 11 August 2014 was annulled when an IVA was approved on 27 May 2015.

During 2016, Harris toured with her show across the UK, An Evening with Anita Harris. With musical accompaniment, she revealed anecdotes from her life in showbusiness, the people she has met and the places she has been. She appeared in ITV‘s Last Laugh in Vegas, and was a contestant in the BBC‘s Celebrity MasterChef 2018.

In 2019, Harris guest starred in the first episode of Series 20 of Midsomer Murders’ entitled “The Ghost of Causton Abbey” as Irene Taylor, an accomplice to the killer.

She will guest star as a medium in an episode of EastEnders which is due to be aired in August 2019.

Anita will be starring in the UK Tour of Cabaret, alongside John Partridge from August 2019 to early 2020.