Jeremy Kemp was born in 1935 in Chesterfield in Derbyshire. He studied in London at the Central School of Speech and Drama. He first came to the attention of the public in the popular TV series “Z Cars” in Britain. He made his film debut in 1965 in “Dr Terror’s House of Horrors”. The following year he had a major role with George Peppard and James Mason in “The Blue Max”. He also starred in “Operation Crossbow”. His other films include “The Strange Affair” with Michael York and Assignment K” with Stephen Boyd. He has acted in Hollywood in many of the popular television drama such as “Hart to Hart”, “Winds of War, “War & Remberance”,”The Fall Guy” and “Murder She Wrote”.

A commentary on Jeremy Kemp on the British Film Forum can be accessed here.

The actor Jeremy Kemp, who has died aged 84, was in at the beginning of a piece of TV history when he appeared in the original cast of Z Cars as PC Bob Steele. While Dixon of Dock Green depicted a homely image of the police, Troy Kennedy Martin’s creation was a warts-and-all portrayal of the members of a new crime division set up in the fictional Liverpool suburb of Newtown, with mobile officers in patrol cars Z Victor One and Z Victor Two, and in its early days broadcast live.

In the first episode, directed by John McGrath, Steele was seen at home having lunch with his friend and partner in Z Victor Two, PC Bert Lynch (played by James Ellis). A stain on the wall was explained as the previous night’s hot-pot flung by Steele’s wife, Janey (Dorothy White), during an argument – while she sported a black eye. Steele and Lynch were two of a group of officers selected by DI Charlie Barlow (Stratford Johns) and DS John Watt (Frank Windsor) to tackle a new wave of crime on Britain’s burgeoning housing estates. The others were constables Fancy Smith (Brian Blessed) and Jock Weir (Joseph Brady).

In 1963, less than halfway through the second series, Kemp left the programme for fear of typecasting, also saying that he hated wearing the police uniform. He later gained direct experience of the harsh side of life in the force when, he claimed, he was beaten up in a police cell, but was himself charged with assaulting one of the officers. “I reported a drinking club to the police for not having a proper licence,” he told the Sun in 1985. “What I did not realise was that the club was paying £50 a week protection money.” He was conditionally discharged for a year after being found guilty of assaulting a police sergeant in 1966 by throwing a beaker of water into his face.

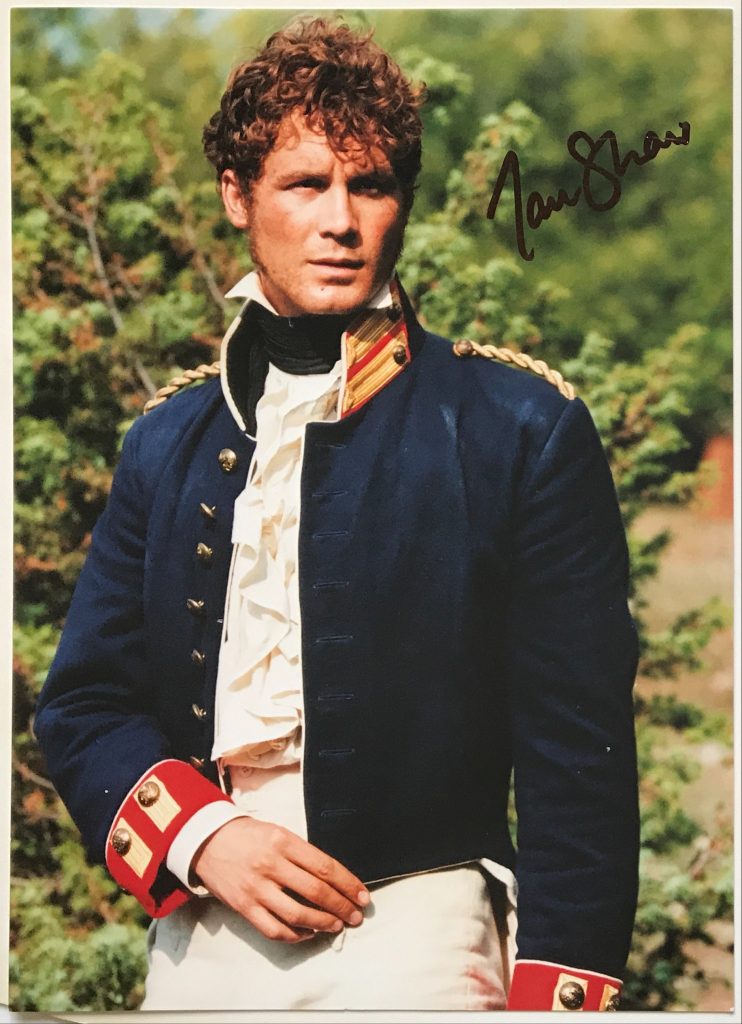

After Z Cars, the craggy-faced Kemp took many character roles on TV and in films. With his 6ft 2in stature and a military bearing, he was often cast as earls, doctors or army officers, such as Brigadier General Armin von Roon in the mini-series The Winds of War (1983) and its sequel, War and Remembrance (1988-89). This fictional officer in the German high command was created by Herman Wouk in the original novels as a device for relaying important facts and tying the story together. He is wounded in an assassination attempt on Hitler and watches the Führer’s gradual decline.

Kemp was also one of the original cast who returned to Z Cars in 1978 for its final episode, written again by Kennedy Martin and directed by McGrath. Kemp played a vagrant, while Blessed was seen simply as a member of the public and Brady was credited as a Scotsman. Ellis had completed the full, 16-year run, with his character by then an inspector.

Born near Chesterfield, Derbyshire, with the name Edmund Jeremy James Walker, the future actor was the son of Elsa (nee Kemp) and Edmund Walker, an engineer from a family of landed gentry who had owned estates in Yorkshire. He started his national service with the Gordon Highlanders and ended up as a lieutenant in the Black Watch before training as an actor at the Central School of Speech and Drama (1955-58), taking his own second name and mother’s maiden name professionally.

Winning a bursary for drama students named after the actor Carleton Hobbs, in 1958 Kemp gained a contract with the BBC’s radio drama company. He made his television debut that year as a police constable in The Frog, a Sunday-Night Theatre production based on Ian Hay’s play. Michael Caine, who also played a constable, later turned down the role taken by Kemp in Z Cars.

The police series helped to bring him film roles. The director Michael Anderson auditioned him for a small part in the spy drama Operation Crossbow (1965), alongside stars including Sophia Loren, John Mills and Trevor Howard, but was so impressed by “the range of his personality” that he catapulted him to a billing above the title.

Complete with moustache and upper-class accent, Kemp played a British agent. A year later, he was in The Blue Max as Lt Willi von Klugermann, the first world war German fighter pilot taking George Peppard under his wing.

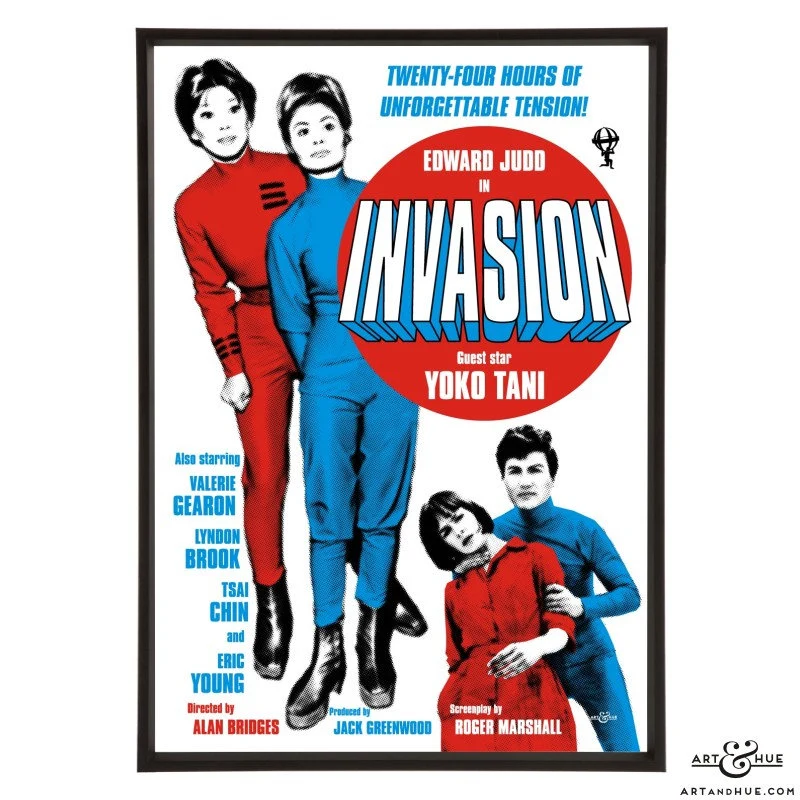

Kemp was also seen as Jerry Drake in Dr Terror’s House of Horrors (1965), the coach of an Indigenous Australian marathon runner in the Olympic drama The Games (1970), Duke Michael in The Prisoner of Zenda (1979) and an East German general in the spy spoof Top Secret! (1984).

On television, he played the Nazi hunter Luke Childs in Contract to Kill (1965), Sqn Ldr Tony Shaw, a captured fighter pilot, in the second series (1974) of Colditz, the British undercover agent Geoffrey Moore in The Rhinemann Exchange (1977), the Duke of Norfolk in Henry VIII (1979), Leontes in The Winter’s Tale (1981), General Gates in George Washington (1984) and Jack Slipper, chasing Ronnie Biggs, in The Great Paper Chase (1988), over which the real-life detective successfully sued the BBC.

After two seasons appearing in the classics at the Old Vic theatre (1958-60), Kemp’s stage roles included Aston in The Caretaker (Mermaid, 1972) and Buckingham in Richard III (Olivier theatre, 1979). His final screen credit came as Hissah Zul in the TV series Conan (1997-98), about the mythical barbarian.

He had a particular interest in birds, and liked to visit the London Wetland Centre in Barnes, south-west London. At various times he lived in Britain and California with his American partner, Christopher Harter. She predeceased him, and he suffered from considerable ill health in later years.

He is survived by two sisters, Gill and Jan.

• Jeremy Kemp (Edmund Jeremy James Walker), actor, born 3 January 1935; died 19 July 2019

“Guardian” obituary