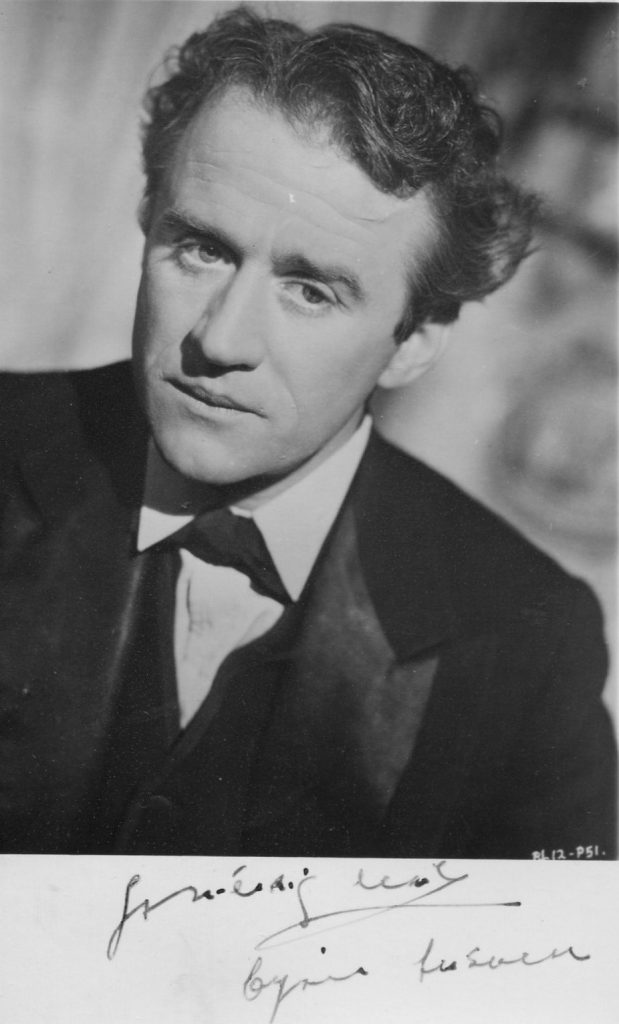

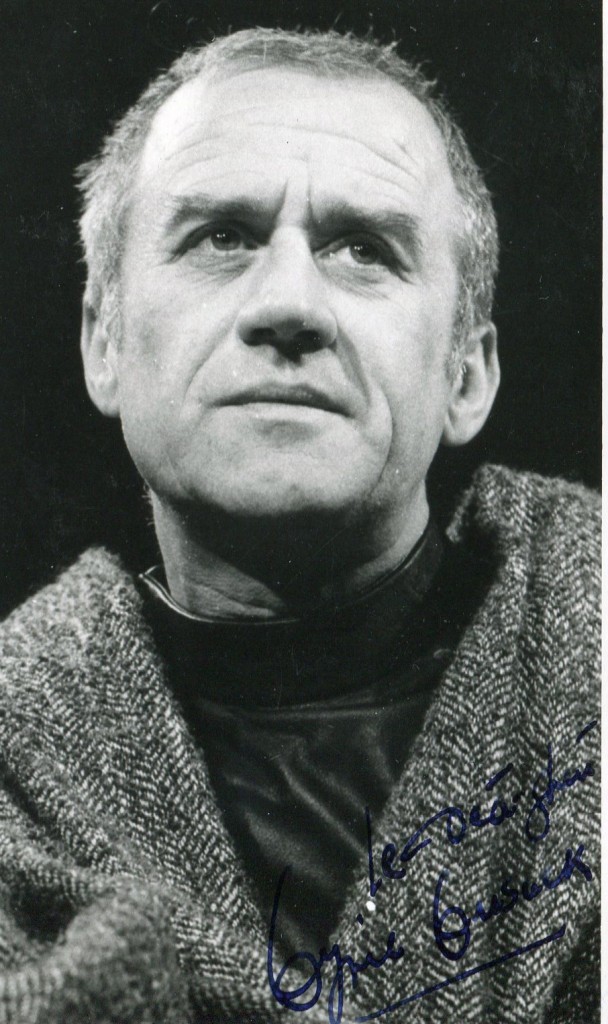

Cyril Cusack obituary in “The Independent”

Cyril Cusack was one of the great Irish actors of theatre and film. He was born in 1910 in fact in South Africa where his parents who were actors were touring in a play. He joined the famed Abbey Theatre in 1932 where he remained until 1945. He acted in over sixty productions and became a particular exponent of the work of Sean O’Casey. He formed his own production company in 1947. His first film was as a child in the 1918 silent film “Knocknagow”. His film career highlights include “Odd Man Out”, “THe Small Back Room”, “Gone to Earth”, “The Rising of the Moon” and “True Confessions”. This film he made in the U.S. in 1981 with Robert De Niro and Robert DuVal. His last stage performance was just a few years before his death where he appeared in “Three Sisters” with his own daughters Sinead , Sorcha and Cusack. His other daughter Catherine Cusack is also an actress. Cyril Cusack died in London in 1993 at the age of 82

.His “Independent” obituary:

ALL that was ever meant by the Irish theatrical tradition in the 20th century was embodied in the life of Cyril Cusack. Soft-voiced, thin-lipped, small-built, fey or sinister, gentle or chilling, poetical, musical, rueful, shy, he was by nature a quietist.

Yet he waved the banner of Irish drama with a loud loyalty to his beloved forebears, Shaw, Boucicault, Synge, O’Casey. He was born abroad, in South Africa in 1910, to an Irish father who was serving in the mounted police, and a cockney mother. But no one learnt better to understand the value and the vicissitudes of Irish fit-ups, those roving companies that strayed from village to village on a once-nightly basis.

He was a boy when his mother’s partner, the Irish actor Brefni O’Rourke, whom he later came to regard as his father, took him on. Cusack graduated in his twenties to the Abbey, Dublin. He played in over 65 of its productions in the early Thirties. He formed his own troupe, the Gaelic Players; and just before the Second World War gave Londoners a taste of his quality.

Not in the West End, of course. But at the minuscule Mercury in Notting Hill Gate, and at the now vanished ‘Q’ on Kew Bridge. Fringe productions we might call them now, but they drew the leading critics of the day to The Playboy of the Western World and The Plough and the Stars.

Here was an actor to reckon with: a melancholic, mischievous, courteous and so arrestingly Celtic, so steeped in his authors, that his Christy Mahon in Synge’s masterpiece – brimming with naive, elfin charm – and his young Covey in O’Casey’s tragi-comedy – a bantam-cock of impertinence – tingled with life and fun and finely controlled expressiveness.

They were to become his best- known parts. He had been playing them for years in Ireland, but they lit up those small west London stages: and even when he made a reputation in other roles, as the dying Louis Dubedat for instance in The Doctor’s Dilemma which brought him into the West End a few years later opposite Vivien Leigh, it seemed as if something of the Covey and of the Playboy informed his characterisation.

He loved Shaw and Shavian parts, and it grieved him as much as it grieved his admirers when on St Patrick’s Day 1942, a fortnight after the opening of The Doctor’s Dilemma, his acting went, to say the least, disturbingly fuzzy. He started introducing into Shaw’s dialogue lines from The Playboy of the Western World – having ‘dried up’, it was the only part he knew he could speak in a crisis – and his mind went blank.

Vivien Leigh also became confused; and the curtain had to come down. Whatever the facts behind a legendary occasion – had Cusack made too much of St Patrick’s Day far from home as the Blitz proceeded? was the wartime whisky bad? had he also got his understudy drunk? – both actors were dismissed. Cusack returned to Dublin to run the Gaiety Theatre with plenty of Shaw, Synge and O’Casey, including the premiere of O’Casey’s The Bishop’s Bonfire (1955).

He played Hamlet. He created a stir in Paris with his production of The Playboy, and in 1960 he won the International Critics Award for his productions at the Theatre des Nations of Arms and the Man and Krapp’s Last Tape. He also worked for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the new National Theatre, but it was his acting as Conn in the Abbey’s revival of Boucicault’s The Shaughran in a World Theatre Season at the Aldwych which proved his main achievement at the time because it provoked a most profitable revival of British interest in Boucicault which was to last for decades.

Cusack served the Dublin Theatre Festival faithfully every autumn. If his own version of The Temptation of Mr O (from Kafka) brought out his whimsicality unduly, his Gayev in The Cherry Orchard was a real charmer: and Londoners were grateful to be able to see his famous Fluther Good in The Plough and the Stars, at the Olivier Theatre in 1974, and his wonderfully sly and insinuative style as The Inquisitor in Saint Joan.

Back at the Abbey in the 1980s he was as moving as he had ever been as the father in Hugh Leonard’s autobiographical A Life, especially at the end when he whirled his umbrella at the audience, smiled wanly and with infinite pathos strolled off stage.

He never ceased to make films either in Britain or Hollywood because he was by nature a reserved actor with a marvellous eye for the telling detail. He seemed to specialise in modest little men: thoughtful, repressed, fey clerks, drunks, priests, dreamers.

His starving boy by the roadside in his first film, Knocknagow (1917), is a collector’s item, but his screen personality insinuated itself more strikingly into the atmosphere of Odd Man Out (1947), The Man Who Never Was (1956), The Waltz of the Toreadors (1962), The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965), Fahrenheit 451 (1966), The Taming of the Shrew (1967), The Day of the Jackal (1973) and True Confessions (1981).

Small parts, of course, but apt to steal their scenes, though I never saw scenes more stirringly or comically stolen than at the Royal Court, in London, in 1990 in a transfer from The Gate, Dublin, of Adrian Noble’s staging of The Three Sisters.

Cusack was the last of the great Irish actor-managers and the father of a theatrical family, and the women of the title in The Three Sisters were played most affectingly by three of his talented children, Sorcha, Niamh and Sinead. But as the drunken army doctor Chebutykin, Cusack himself, with his asides and his sniffs, his murmurs and his stares, his timing, and his wry, ruminative smile, stole hearts with the subtlety and truth of his under-playing.

His “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.

TCM overview:

Gifted Irish stage performer, born in South Africa who made his film debut in 1917’s “Knocknagow”, but did not come into his own as a strong screen character actor until 1947 with Carol Reed’s “Odd Man Out”. With his quirky features, playful authority and an elfin face that sometimes registers melancholy or stern morality, Cusack most often portrayed clerics (“My Left Foot” 1989) but in “The Spy Who Came in from the Cold” (1965), he played the spy chief and in Truffaut’s “Fahrenheit 451” (1966), the book-burning fire chief. One of the most acclaimed stage actors of his generation, Cusack was famous for his association with Ireland’s national theater, the Abbey; he was at various times also affiliated with Old Vic and the Royal Shakespeare Company. Cusack also performed on Broadway, as in the memorable 1957 staging of Eugene O’Neill’s “A Moon for the Misbegotten” in which he starred opposite Wendy Hiller. Active in theatre administration and production as well, he managed the Gaity Theater in Dublin for a while in the 1940s and founded his own Cyril Cusack Productions in 1944. He is the father of actresses Sinead, Niamh and Sorcha Cusack with whom he co-starred in the 1990 Gate Theater of Dublin’s production of “The Three Sisters”.

Dictionary of irish biography

Cusack, Cyril James (1910–93), actor, director, and writer, was born 26 November 1910 in Durban, South Africa, son of James Walter Cusack, an Irish officer with the Natal mounted police, and Alice Violet Cusack (née Cole), a Cockney chorus girl, who was related to the music-hall star Dan Leno. After his parents separated (1916), Cyril and his mother left for London, and soon afterwards went to Ireland, with the actor-manager De Brefni O’Rorke (1889–1946), whom Cyril always referred to as his stepfather but whom his mother never married. The trio joined the O’Brien and Ireland Players, a nomadic ‘fit-up’ company which, as Cyril nostalgically recalled in later life, played a different town every week. He appeared in countless juvenile parts, including the cat in ‘Dick Whittington’ and a girl in ‘Shot at dawn’. In his film debut (1918) as an evicted waif in a dramatisation of Charles Kickham’s Knocknagow, he showed early professionalism by waiting until the end of the shot before yelling, having sat on a clump of nettles. He travelled periodically to London with the company, and changed schools with each move, later claiming to have attended every school in Ireland. He loved the peripatetic life, the makeshift shows, and the melodramatic fare and made a point, throughout an illustrious career appearing in largely highbrow work, of celebrating his early influences: ‘My alma mater was the touring theatre’ (quoted in Hickey & Smith, 26).

In 1923 he became a boarder at the Dominican College, Newbridge, Co. Kildare, and stopped touring. Momentarily seduced by the desire for a safer, more conventional career, he entered UCD (after a short period in the CBS, Synge St.) to study politics and law with the intention of applying for the bar. His friends included Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh (qv) and Frank Ryan (qv), who encouraged his republican beliefs – the trio were evicted from a lecture for making seditious comments. During holidays Cusack worked as an actor with various repertory companies, including Norwich and Windsor. Appearing in Brixton, he described how ‘something happened between myself and the audience – I suddenly realised that they liked me’ (ibid., 25). He left college without a degree and, after a year touring with his mother and O’Rorke round England and Ireland, made his debut in the Abbey in 1932, playing two small parts in A. P. Fanning’s one-act ‘Vigil’. The diarist Joseph Holloway (qv) wrote perceptively of his soft, musical voice and great promise – the first of Cusack’s almost invariably excellent reviews. At the Gate, Hilton Edwards (qv) and Mícheál MacLiammóir (qv) spotted his potential and gave him two seasons, but MacLiammóir later regretted that they gave him only juvenile parts and lost him to the Abbey. He played almost exclusively with the Abbey between 1933 and 1945, appearing frequently in major roles in over sixty-five productions.

Cusack was small, neat, graceful, and a natural scene-stealer to whom audiences responded warmly. Interaction with the audience mattered greatly to him and he placed theatre above film ‘because a film may be seen by six million, and a play by only 600, but the effect on the 600 may be truer and more lasting’ (Mikhail, 205). Patricia Boylan (qv), a young Abbey actress in the 1930s, felt he was too dependent on the audience liking him and that this hindered him in playing unsympathetic roles, but she testified to his intensity and commitment, recalling how he once took a long walk with her, remaining the whole time in character. Such immersion in a part came close to the ‘method acting’ style popularised in later decades in America, and Cusack was an important bridge between the old-school Abbey acting and the newer generation. He greatly admired the older actors Barry Fitzgerald (qv) and F. J. McCormick (qv), but he agreed with the English director Hugh Hunt (qv) that Abbey acting had become rhetorical and stylised, and he was instrumental in Hunt’s drive to make it more naturalistic. His performance as Christy Mahon in Hunt’s production of ‘The playboy of the western world’ (27 July 1936), which he described as ‘a fine balance of naturalism with the theatrical’ (Whitaker, 50), so enraged the Abbey director, F. R. Higgins (qv), that he stormed into Cusack’s dressing room and made a scene. The run continued – it was a commercial success – but immediately after the play was directed again, by Higgins, in more conventional Abbey style.

Cusack’s occasional appearances in London during this period – ‘Ah wilderness’ (1936), ‘The plough and the stars’ (1939), ‘Thunder Rock’ (1941) – earned him good notices, but his career in England suffered a severe setback when he appeared as Dubedat in ‘The doctor’s dilemma’ opposite Vivien Leigh at the Haymarket in 1942. He received good initial reviews but spent St Patrick’s day drinking with his understudy, so that his performance that night deteriorated to quoting large sections of ‘Playboy’. He was ordered off and replaced by the understudy, to no noticeable improvement. Both were sacked the next day and a mortified Cusack entered a largely self-imposed twenty-year exile from the West End.

In Ireland he grew increasingly dissatisfied with the Abbey, which he felt had an obligation, as the national theatre, to tour the provinces and to take shows abroad. Always an enthusiast for the Irish language, he was instrumental in the formation of the Gaelic Players, which put on Irish plays, including one written by Cusack, ‘Tar éis an Aifrinn’ (1942). In 1945 he left the Abbey to set up his own company, Cyril Cusack Productions, which toured the country with Irish and European plays, and when in Dublin had residence in the Gaiety Theatre, which Cusack managed. Running his own company suited his temperament; he was renowned for his dislike of directors, whom he felt had become overly influential since his days with the actor-run ‘fit-ups’. In 1954 he produced an acclaimed ‘Playboy’ with himself in the title role, Siobhán McKenna (qv) as Pegeen Mike, and appearances by Jack MacGowran (qv), Marie Kean (qv), and Walter Macken (qv). It was the only Irish production chosen for the first international drama festival in Paris in 1954, where it was singled out as one of the best shows. He took the company to the Paris festival again in 1961, where he received the international critics’ award for his performances in ‘Krapp’s last tape’ and ‘Arms and the man’.

In 1955 his company presented the world premiere of the controversial new play by Sean O’Casey (qv), ‘The bishop’s bonfire’, after Cusack visited O’Casey in Torquay to persuade him to showcase his new work in Dublin. The play (typically for O’Casey) was anti-clerical; Cusack, the devout, mass-going president of the Catholic Stage Guild, probably disagreed with its sentiments, but appreciated its pulling power. The performance, directed by Tyrone Guthrie (qv), was condemned in advance by a small catholic action group, and this guaranteed audiences. Critics came from Britain and America, and on the opening night (28 February) 2,000 people had formed a queue down Grafton St., and police were called to keep order. The expected uproar began in the second act but was led by a small faction of the audience; the majority remained bemused. Cusack made a curtain speech – beginning in Irish, and switching to English on demand – in which he derided the ‘self-appointed defenders of God in the manger’ (Irish Press, 1 Mar. 1955). However, his ambiguous attitude towards the play – not a critical success, then or later – must have been apparent, because Conor Cruise O’Brien wrote that his speech was delivered ‘with the air of Ajax defending a damp Monday evening’ (New Statesman and Nation, 5 Mar. 1955).

Cusack harboured ambitions all his life to write, and published a number of poetry books; however, the poor reception of his play ‘The temptation of Mr O’ (1961) – based on Kafka’s Trial and written in Dublinese – so dismayed him that he never wrote another. It also heralded the end of his stage company, which he had been largely supporting through his film work. In later life, Cusack claimed not to rate film and said he only took on the work to pay for his acting tours, yet his naturalistic style suited the screen and he was an accomplished film actor. He appeared in the first film of Denis Johnston (qv), ‘Guests of the nation’ (1935), adapted from the Frank O’Connor (qv) short story, and notable for its cast, which included Hilton Edwards, Denis O’Dea (qv), and Barry Fitzgerald. His small but scene-stealing role as a getaway driver in Carol Reed’s Odd man out (1947) brought him praise and regular work, and established him as a character actor. In a career of ninety films he worked with major directors including Zefferelli, Truffaut, and Zinnemann, and occasionally played the lead – Galileo (1968), Sacco e Vanzetti (1971) – but was seen to best effect in small parts in short, concentrated scenes. In The spy who came in from the cold (1965), he has only two scenes but successfully conveys a ruthless schemer under a prissy exterior. This role and others challenge Truffaut’s curious observation that Cusack could not be terrifying. He was equally successful on the small screen, appearing in over seventy-five TV productions, including ‘Strumpet city’ (RTE, 1980), in which he played a priest, and the popular ‘Glenroe’ series, in which he appeared as Uncle Peter. Among his favourite roles was as a poitín maker in a low-budget Irish-language film, Poitín (1979).

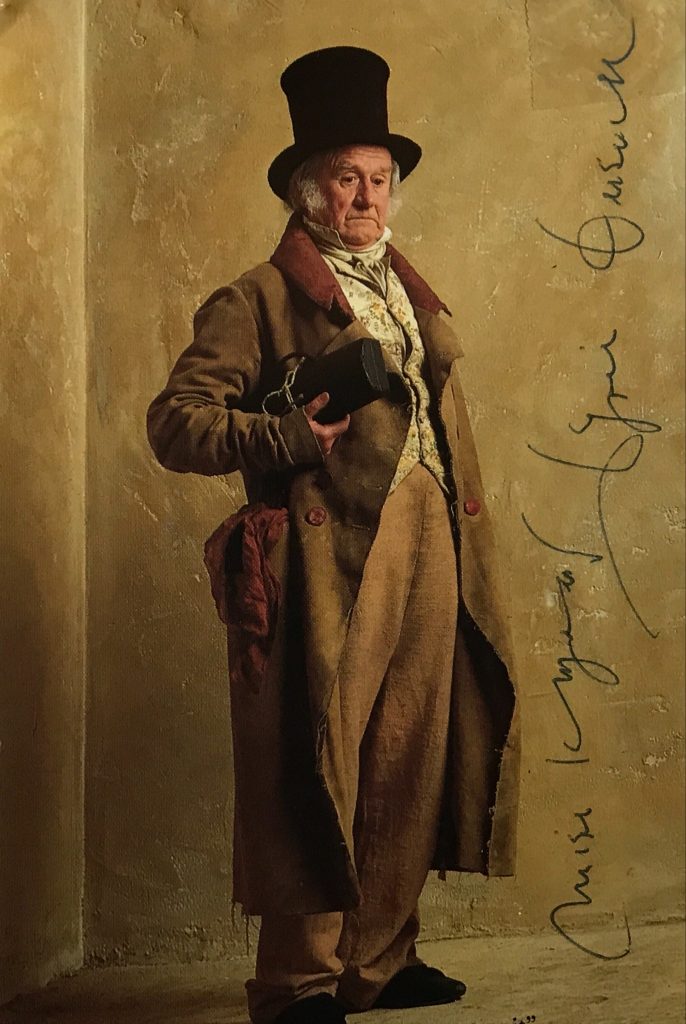

After the demise of Cyril Cusack Productions he joined the Royal Shakespeare Company as Mobius in Dürrenmatt’s ‘The physicians’ (1963). His return to the West End was hailed by Bernard Levin in the Daily Mail (‘A thousand times welcome back!’), and he enjoyed acclaimed seasons with the National Theatre as well as the RSC. During this decade he also returned to the Abbey, first as a shareholder, before achieving his dream of reviving Boucicault (qv) with his performance of ‘The shaughraun’ (31 January 1967). Ironically, the Times critic (3 March 1959) had complained of a 1959 production of Harry V. Tarvin’s ‘Goodwill ambassador’ that ‘Mr Cyril Cusack, a former Abbey actor of great stature, was lending himself to stage Irishism’, unaware that Cusack preferred the melodramatic tradition, which he described as ‘theatre theatrical not theatre of the intellect’ (Smith, 28) and wanted to bring it to the Abbey. The success of ‘The shaughraun’, in which he played the title role, was a vindication of his beliefs. The following year he gave full rein to his genius for tragicomedy as the talkative and eccentric Gayev in ‘The cherry orchard’ (Abbey, 8 October 1968). Its Russian director, Maria Knebel, who had known the Chekhov family, told him that he was born to play Gayev. Of Cusack’s acting style, MacLíammóir noted that ‘his sense of the detail of reality is well-nigh perfect; to the smallest things that help us believe in a character, he brings delicacy and precision’ (MacLíammóir, 348). Alec Guinness wrote that Cusack was one of only three actors whom he revered this side of idolatry.

Cusack was a complex and enigmatic character, even to himself – he remarked in one interview that his New Year’s resolution was to find out who he was. Known for his whimsical charm and twinkling smiles, he could make cutting remarks in a deceptively light tone. A pious catholic, who entered the abortion debate on the Irish Times letters page to oppose abortion, he was also adulterous and was rumoured to have had an affair with Vivien Leigh, among others. His wife, the Derry-born actress Mary Margaret (‘Maureen’) Kiely (m. 1945), suffered through his infidelities, and the couple separated (after having six children, one of whom died at birth) about 1968, the year his girlfriend, Mary Rose Cunningham, gave birth to his fourth daughter. Cusack continued to preach family values and did not marry Cunningham until 1979, two years after his first wife’s death.

His career in old age remained distinguished – he appeared in Jim Sheridan’s My left foot (1989) and the following year Adrian Noble cast him opposite his three eldest daughters, Sinead, Sorcha, and Niamh, in Chekhov’s ‘The three sisters’, which had a triumphant run at the Gate. He died of motor neurone disease at 41 Burlington Lane, Chiswick, London, on 7 October 1993 and was buried at Bohernabreena cemetery, Dublin. The dáil observed a minute’s silence to mark his death.

Micheál MacLíammóir, All for Hecuba (1946), 348; Cyril Cusack, ‘A player’s reflections on Playboy’, Thomas R. Whitaker (ed.), Twentieth century interpretations of The Playboy of the Western World: a collection of critical essays (1969); Cyril Cusack, ‘Cusack: every week a different school’, Des Hickey and Gus Smith (ed.), Flight from the Celtic twilight (1973); Brian McIlroy, ‘Interview with Cyril Cusack’, World cinema 4: Ireland (1988); E. H. Mikhail, The Abbey theatre: interviews and recollections (1988); Times, Guardian, Independent, Daily Telegraph, Ir. Times, 8 Oct. 1993; Sunday Independent, 21 Nov. 1993; International directory of films and filmmakers, iii: Actors and actresses (1997); Robert Welch, The Abbey Theatre, 1899–1999 (1999); Patricia Boylan, Gaps of brightness (2003); Christopher Murray, Sean O’Casey (2004)